The federal Central Valley Project (CVP) is the state’s largest water supplier and the largest of the Bureau of Reclamation’s seventeen irrigation projects. The CVP delivers 7 million acre-feet of water on average each year to irrigate 3 million acres or about one-third of California’s irrigated lands, as well as supply drinking water for 1 million households. The CVP also provides hydroelectric power, flood protection, recreation, and water quality benefits, and supplies much of water for the state’s wildlife refuges.

The federal Central Valley Project (CVP) is the state’s largest water supplier and the largest of the Bureau of Reclamation’s seventeen irrigation projects. The CVP delivers 7 million acre-feet of water on average each year to irrigate 3 million acres or about one-third of California’s irrigated lands, as well as supply drinking water for 1 million households. The CVP also provides hydroelectric power, flood protection, recreation, and water quality benefits, and supplies much of water for the state’s wildlife refuges.

Construction of the Central Valley Project

At the turn of the century, California had the fastest growing population and economy; however, the state’s variable climactic swings of droughts and floods required infrastructure beyond the ability of local communities to construct on their own. This drove a focus from local water supply and flood control projects to larger inter-regional projects that could move and manage water over longer distances.

At the same time, the growth of irrigated agriculture in the Central Valley was reducing flows of freshwater into the Delta, causing salt water to intrude inland, affecting croplands, hindering industrial development, and impacting Antioch and Pittsburg’s water supply. By 1926, salinity intrusion forced Antioch and Pittsburg to stop drawing water from Suisun Bay for agricultural and industrial use, a source the cities had used since the mid-nineteenth century.

For decades, sporadic efforts had been made by various local, state and federal agencies to channel water from the mountainous areas to the lower lying areas for agriculture, but it wasn’t until the Marshall Plan was developed in 1919 did the idea of a statewide scheme of reservoirs and canals gain traction. The Marshall Plan became the basis for the 1930 State Water Plan, and in 1933, the state legislature authorized the project and the sale of revenue bonds. However, in the era of the great Depression, there were few buyers. Eventually, the state asked the federal government to step in with President Franklin Roosevelt authorizing the project in December of 1935.

The Rivers and Harbors Act of 1937 reauthorized the project and appropriated funds for its construction. Later that year, construction began on the Contra Costa Canal with water delivered to the East Bay for the first time in 1940. Construction of Shasta Dam began in 1938 and was completed by 1945. Over the next three decades, Congress would pass thirteen separate measures to authorize additional facilities with the final dam, New Melones, completed in 1979.

The Rivers and Harbors Act of 1937 reauthorized the project and appropriated funds for its construction. Later that year, construction began on the Contra Costa Canal with water delivered to the East Bay for the first time in 1940. Construction of Shasta Dam began in 1938 and was completed by 1945. Over the next three decades, Congress would pass thirteen separate measures to authorize additional facilities with the final dam, New Melones, completed in 1979.

Central Valley Project Facilities

Today, the CVP consists of 18 dams and reservoirs, 11 power plants, three fish hatcheries, and 500 miles of canals and aqueducts. The Central Valley Project does not consist of contiguous faculties, and is therefore divided into eight divisions, some of which work in conjunction with other divisions, while other divisions operate completely independently. The Central Valley Project delivers irrigation water to an area spanning the length of the Central Valley from Shasta Reservoir to Kern County; Central Valley Project water also serves water for urban uses in the Bay Area and parts of the Central Valley.

Benefits and impacts of the Central Valley Project

The Central Valley Project is not only the state’s largest water project, but also perhaps its most controversial. When the project was authorized during the Great Depression, some of the environmental consequences could be foreseen, yet the decision was made to go ahead anyway, with the belief that creating an abundant supply for the farms and cities would serve the greater good.

Certainly, the benefits of the Central Valley Project to the state and to the nation have been incalculable. The construction of the Central Valley Project helped propel California to the top as the largest agricultural state in the country, providing inexpensive food and fiber to the nation and to the world. California has led the nation in agricultural and dairy production for the last 50 years. The Central Valley and the Delta produce 25% of the nation’s table food on only 1% of the country’s farmland. Fresno County is the most productive county in the nation, growing 350 crops worth more than $1 billion. Six of the state’s top ten agricultural counties are in the San Joaquin Valley.

Certainly, the benefits of the Central Valley Project to the state and to the nation have been incalculable. The construction of the Central Valley Project helped propel California to the top as the largest agricultural state in the country, providing inexpensive food and fiber to the nation and to the world. California has led the nation in agricultural and dairy production for the last 50 years. The Central Valley and the Delta produce 25% of the nation’s table food on only 1% of the country’s farmland. Fresno County is the most productive county in the nation, growing 350 crops worth more than $1 billion. Six of the state’s top ten agricultural counties are in the San Joaquin Valley.

In addition, the availability of water and power from the Central Valley Project and other water development projects brought manufacturing and commerce to the state and created millions of jobs in the process. Central Valley Project facilities have prevented billions of dollars of damage from floods, and allowed cities and farms to grow and prosper on the valley floor.

However these benefits were not achieved without a heavy price. In Northern California, the filling of Shasta Reservoir inundated traditional Native American lands and the diversion of up to 90% of the flow of the Trinity River water into the Sacramento River basin has decimated salmon and steelhead populations, creating intense conflict between the United States and Native American tribes in the area which continues to this day.

However these benefits were not achieved without a heavy price. In Northern California, the filling of Shasta Reservoir inundated traditional Native American lands and the diversion of up to 90% of the flow of the Trinity River water into the Sacramento River basin has decimated salmon and steelhead populations, creating intense conflict between the United States and Native American tribes in the area which continues to this day.

The construction of Shasta, Friant and other dams did not include fish ladders, blocking access to much of the spawning grounds on the upper Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and tributaries. Attempts to offset the losses through using hatcheries have essentially failed. Further downstream, freshwater wetlands that once provided habitat for a myriad of fish, migratory birds, and terrestrial species were drained and reclaimed for farming.

The San Joaquin River has paid a heavy price when the entire flow of the river was diverted at Friant Dam, leaving an intermittently dry riverbed for 150 miles. Since construction of the dam, the riverbed below Friant Dam has functioned primarily as a regional drain and flood control channel.

However, In recent decades, efforts have been underway to address the impacts, including the Central Valley Project Improvement Act, the San Joaquin River Restoration Program, and the Trinity River Restoration Program.

The Central Valley Project Improvement Act

Changing environmental and social values brought changes to the operation of the Central Valley Project, culminating in the 1992 Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA), which was intended to address the CVP’s environmental impacts. The CVPIA added water for the environment as one of the stated purposes of the project, requiring the dedication of 800,000 acre-feet of CVP water towards the restoration of fisheries as well as firm supplies for wildlife refuges. Provisions also addressed issues, such as water transfers, contract terms, and tiered water pricing.

Changing environmental and social values brought changes to the operation of the Central Valley Project, culminating in the 1992 Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA), which was intended to address the CVP’s environmental impacts. The CVPIA added water for the environment as one of the stated purposes of the project, requiring the dedication of 800,000 acre-feet of CVP water towards the restoration of fisheries as well as firm supplies for wildlife refuges. Provisions also addressed issues, such as water transfers, contract terms, and tiered water pricing.

Environmentalists considered passage of the CVPIA a victory, while the agricultural community considered it a disaster. Over 20 years later, despite millions of dollars spent and thousands of acre-feet of water, the benefits to the fish populations have yet to be realized, and the controversy remains.

For more information …

- Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA), webpage by Bureau of Reclamation

- Comprehensive Assessment and Monitoring Program (CAMP), webpage by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The CAMP program assesses overall effectiveness of CVPIA habitat restoration actions in the Central Valley and the relative effectiveness of habitat restoration methods.

- Anadromous Fish Restoration Program, webpage by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.The Anadromous Fish Restoration Program is tasked by the Central Valley Project Improvement Act to ‘make all reasonable efforts to at least double natural production of anadromous fish in California’s Central Valley streams on a long-term, sustainable basis.’

San Joaquin River Restoration

The construction of Friant Dam completely dried out portions of the San Joaquin River. In September 2006, a settlement was reached in an 18-year lawsuit between the Department of Interior, Department of Commerce, NRDC, and the Friant Water Users Authority to provide sufficient fish habitat in the San Joaquin River from Friant Dam to the confluence of the Merced River. The settlement had the two goals of restoring and maintaining fish populations and reducing or avoiding water supply impacts to the Friant Division. Legislation in March of 2009 authorized the federal agencies to implement the settlement.

The construction of Friant Dam completely dried out portions of the San Joaquin River. In September 2006, a settlement was reached in an 18-year lawsuit between the Department of Interior, Department of Commerce, NRDC, and the Friant Water Users Authority to provide sufficient fish habitat in the San Joaquin River from Friant Dam to the confluence of the Merced River. The settlement had the two goals of restoring and maintaining fish populations and reducing or avoiding water supply impacts to the Friant Division. Legislation in March of 2009 authorized the federal agencies to implement the settlement.

Eight years and $100 million later, the project has shown little results. Re-watering the dried river bed has caused groundwater seepage issues with surrounding properties, and necessary channel improvements and facilities have yet to be constructed. Costs have escalated as key deadlines have been missed. In February of 2014, water meant for the program was reallocated to Central Valley communities for drinking water as extreme drought conditions wreaked havoc statewide. Releases of water won’t resume at least until March of 2015, depending on conditions.

For more information …

- San Joaquin River Restoration Program, official website

- San Joaquin River Restoration Program: Salmon Conservation and Research Facility and Related Management Actions Project, from the California Department of Fish and Game

- Restoring the San Joaquin River, webpagefrom the NRDC

Trinity River Restoration

The completion of Trinity Dam in 1964 diverted between 75% and 90% of the Trinity River’s flow, which reduced salmon and steelhead runs by more than 80%. In 1992, the CVPIA established minimum flows of 340,000 acre-feet for the Trinity River. In 2002, a Record of Decision was signed to implement the Trinity River Restoration Program with the goal of restore naturally-spawning salmon and steelhead populations to near pre-dam levels. The program, a partnership between state and federal agencies and Native American tribes, is considered the largest salmonid restoration project in the state.

The completion of Trinity Dam in 1964 diverted between 75% and 90% of the Trinity River’s flow, which reduced salmon and steelhead runs by more than 80%. In 1992, the CVPIA established minimum flows of 340,000 acre-feet for the Trinity River. In 2002, a Record of Decision was signed to implement the Trinity River Restoration Program with the goal of restore naturally-spawning salmon and steelhead populations to near pre-dam levels. The program, a partnership between state and federal agencies and Native American tribes, is considered the largest salmonid restoration project in the state.

The program has come under fire with critics saying the program’s governance lacks a shared and consistent vision and that the projects do more harm than good. Their case was bolstered when in January of 2014, a science advisory panel determined that the program had failed to produce any significant benefits and has veered significantly from its original intent.

For more information …

- Trinity River Restoration Program webpage: The TRRP is a multi-agency program with eight Partners forming as the Trinity Management Council (TMC), plus numerous other collaborators.

- Bureau of Reclamation factsheet

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife factsheet

- Trinity River Restoration Program Administrative and Governance Problems, webpage by C-WIN

Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge

The completion of the facilities at San Luis in the 1960s brought more land into production on the Central Valley’s west side. However, these lands sit atop a layer of an impermeable layer of clay and require an extensive drainage system in order to be farmed. The Bureau of Reclamation agreed to build a drainage system to remove the water and discharge it to the Delta; however, when Congress failed to appropriate funds for construction of the drain, the water was allowed to pool at Kesterson National Wildlife Refuge. The drainage water contained salts, selenium, and heavy metals which are natural components of the soil, and over time, they accumulated. By the 1970s, biologists started discovering high rates of birth defects in birds hatched in the area, and soon identified toxic levels of selenium as the cause. The site was subsequently closed and sealed from further use to protect wildlife and public health. Thousands of acres of farmland have had to be retired due to salinization of the land. Lawsuits ensue still to this day; the drain has yet to be constructed.

For more information …

- Kesterson Reservoir, the Wikipedia page

- Kesterson Reservoir, page from C-WIN

- Articles about Kesterson, archive at the Los Angeles Times

Possible expansion of Central Valley Project facilities

Shasta Lake Water Resources Investigation (or Shasta Dam Enlargement): This project proposes to raise Shasta Dam by 6.5 to 18.5 feet, thereby expanding Shasta Resevoir by 256,000 to 634,000 acre-feet, depending on the alternative chosen. In February of 2012, the Bureau of Reclamation released a Draft Feasibility Study that determined the project was both technically and environmentally feasible, as well as economically justified; the study determined that raising the dam 18.5 feet would cost just over $1 billion dollars and would produce from $18 to $63 million in net economic benefits per year. In June of 2013, the Bureau of Reclamation released an EIS for 90-day public review. The project needs Congressional approval, among other things, to move forward.

Shasta Lake Water Resources Investigation (or Shasta Dam Enlargement): This project proposes to raise Shasta Dam by 6.5 to 18.5 feet, thereby expanding Shasta Resevoir by 256,000 to 634,000 acre-feet, depending on the alternative chosen. In February of 2012, the Bureau of Reclamation released a Draft Feasibility Study that determined the project was both technically and environmentally feasible, as well as economically justified; the study determined that raising the dam 18.5 feet would cost just over $1 billion dollars and would produce from $18 to $63 million in net economic benefits per year. In June of 2013, the Bureau of Reclamation released an EIS for 90-day public review. The project needs Congressional approval, among other things, to move forward.

- For documents and more information from the Bureau of Reclamation, click here.

- For the latest news on this project posted on Maven’s Notebook, click here.

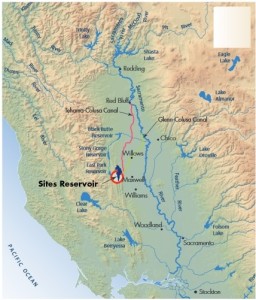

North of Delta Offstream Storage Investigation (or Sites Reservoir): This project proposes to build a new reservoir 10 miles north of Maxwell in Colusa County. Water would be diverted during periods of high flow through existing canals into the off-stream reservoir. The alternatives range from 1.2 to 1.8 MAF reservoir that proponents say would provide an additional 500,000 AF per year of water for use, as well as multiple benefits to the ecosystem. The operations of the reservoir, if built, would be integrated with existing state and federal projects to provide broader statewide benefits. The project would be a joint federal-state project, and so involves both the Bureau of Reclamation and the Department of Water Resources. In 2013, the Bureau of Reclamation issued a progress report on the project. In 2015, the Department of Water Resources released a highlights document and a public administrative draft EIR for informational purposes while the project works to secure funding and local support.

North of Delta Offstream Storage Investigation (or Sites Reservoir): This project proposes to build a new reservoir 10 miles north of Maxwell in Colusa County. Water would be diverted during periods of high flow through existing canals into the off-stream reservoir. The alternatives range from 1.2 to 1.8 MAF reservoir that proponents say would provide an additional 500,000 AF per year of water for use, as well as multiple benefits to the ecosystem. The operations of the reservoir, if built, would be integrated with existing state and federal projects to provide broader statewide benefits. The project would be a joint federal-state project, and so involves both the Bureau of Reclamation and the Department of Water Resources. In 2013, the Bureau of Reclamation issued a progress report on the project. In 2015, the Department of Water Resources released a highlights document and a public administrative draft EIR for informational purposes while the project works to secure funding and local support.

- For Reclamation’s webpage and documents on the project, click here.

- For the Department of Water Resources webpage and documents, click here.

- For the latest news and on this project posted on Maven’s Notebook, click here.

Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation (or Temperance Flat): For decades, water officials have wanted to expand Friant Dam’s 520,000 acre-feet Millerton Lake reservoir, saying that the reservoir is too small for the 1.8 MAF annual inflow. The Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation proposes to build a 665-feet dam at Temperance Flat, 6.8 miles upstream of Friant Dam, partially inside the back end of Millerton Lake. Construction of Temperance Flat would add substantial storage to the system, creating a reservoir upstream with a capacity roughly two and a half times the size of Millerton Lake. A feasibility report on the project and an environmental impact statement were released for public comment in 2014.

Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation (or Temperance Flat): For decades, water officials have wanted to expand Friant Dam’s 520,000 acre-feet Millerton Lake reservoir, saying that the reservoir is too small for the 1.8 MAF annual inflow. The Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation proposes to build a 665-feet dam at Temperance Flat, 6.8 miles upstream of Friant Dam, partially inside the back end of Millerton Lake. Construction of Temperance Flat would add substantial storage to the system, creating a reservoir upstream with a capacity roughly two and a half times the size of Millerton Lake. A feasibility report on the project and an environmental impact statement were released for public comment in 2014.

- For more information on the Upper San Joaquin River Basin Storage Investigation or Temperance Flat project, click here.

- For the latest news on the project posted on Maven’s Notebook, click here.

San Luis Reservoir Low Point Improvement Project (or San Luis Reservoir Expansion, or Sisk Dam raise): In December of 2013, the Bureau of Reclamation issued a draft appraisal report on the possibility of enlarging San Luis Reservoir by raising Sisk Dam as part of necessary seismic improvements. The draft report estimates that it would cost $360 million to raise the dam by 20 feet, expanding the reservoir by 130,000 acre-feet. The Draft Appraisal Report recommends that Reclamation further explore opportunities for enlarging the dam, with its partners, the State Department of Water Resources, the Santa Clara Valley Water District and the San Luis & Delta-Mendota Water Authority.

San Luis Reservoir Low Point Improvement Project (or San Luis Reservoir Expansion, or Sisk Dam raise): In December of 2013, the Bureau of Reclamation issued a draft appraisal report on the possibility of enlarging San Luis Reservoir by raising Sisk Dam as part of necessary seismic improvements. The draft report estimates that it would cost $360 million to raise the dam by 20 feet, expanding the reservoir by 130,000 acre-feet. The Draft Appraisal Report recommends that Reclamation further explore opportunities for enlarging the dam, with its partners, the State Department of Water Resources, the Santa Clara Valley Water District and the San Luis & Delta-Mendota Water Authority.

For more information on the Central Valley Project

- About the Central Valley Project, from the Bureau of Reclamation: Details on Central Valley Project facilities and their history

- Overview of the Central Valley Project: The overview of the CVP included with the ‘2012 Report of Accomplishments’ gives plenty of details and information.

- Central Valley Project Operations Office: Bureau of Reclamation webpage with the latest water operations, reservoir reports, and more.

- Central Valley Project Wikipedia page

Click here to return to the California Water Infrastructure main page.

This page written and posted by Chris (Maven) Austin on September 15, 2014. Last updated July 5, 2015.