Study sets the baseline for meeting the Delta Plan’s ecosystem restoration targets

The Delta Reform Act of 2009 established the Delta Stewardship Council and directed the Council to develop the Delta Plan, a comprehensive, long-term, legally enforceable plan to guide the management of the Delta’s water and environmental resources. The legislation also required the Delta Plan to include measures to track the performance and implementation of the Plan.

The first Delta Plan, adopted in 2013, included a set of initial performance measures that were later refined and updated in 2018 to reflect the best available science and the amendments made in recent years. Currently, the Delta Plan has 154 performance measures that track output and outcomes in areas such as water supply, ecosystem, Delta as an evolving place, water quality, flood management, and administrative actions. You can view all the performance measures here: https://viewperformance.deltacouncil.ca.gov/

In June 2022, the Council adopted an amendment to Chapter 4, Protect, Restore, and Enhance the Delta Ecosystem, of the Delta Plan. The new amendment includes recommendations, updated regulations, problem statements, and performance measures. The amendment also identifies restoration targets of 60-80,000 acres above a 2007 baseline by 2050, with performance measures detailing acreages for specific ecosystem types.

In June 2022, the Council adopted an amendment to Chapter 4, Protect, Restore, and Enhance the Delta Ecosystem, of the Delta Plan. The new amendment includes recommendations, updated regulations, problem statements, and performance measures. The amendment also identifies restoration targets of 60-80,000 acres above a 2007 baseline by 2050, with performance measures detailing acreages for specific ecosystem types.

To determine progress toward the targets, it’s important to understand how much restoration has occurred since 2007. So at the November meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, Senior Environmental Scientist Dylan Chapple provided an overview of the draft ecosystem restoration progress report that sets the baseline for tracking restoration performance measures.

The target of 60-80,000 acres is about twice the size of the city of San Francisco and about 8% of the total land area of the Delta and Suisun Marsh. The target was derived from existing science-based recovery plans and over a dozen agency documents. The results will inform the activities of the Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee (DPIIC) Restoration Subcommittee, which brings together state agencies to identify opportunities for implementing restoration targets across different agency efforts. In addition, the results will be detailed in a journal paper that is being prepared.

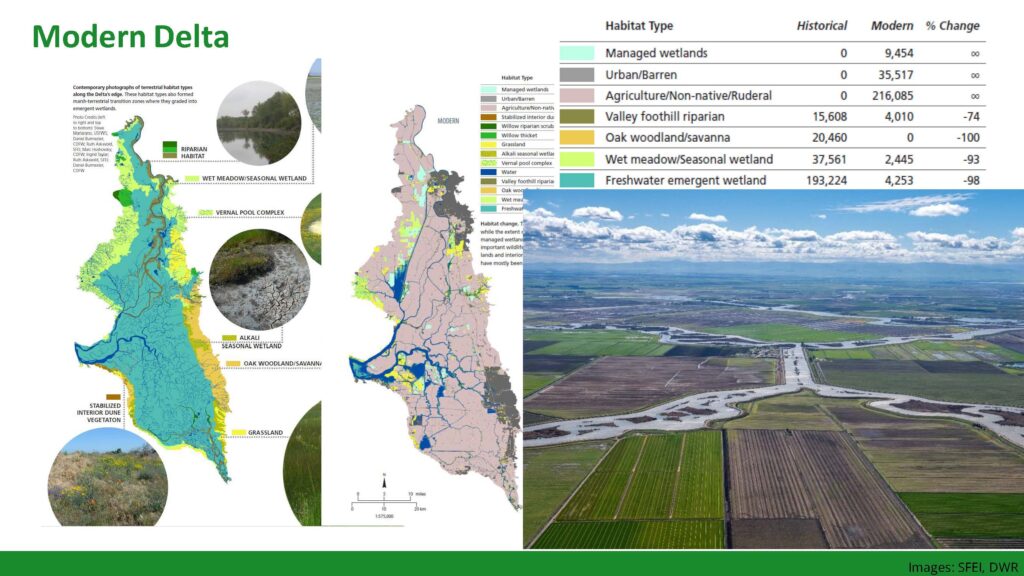

The Delta’s changed landscape

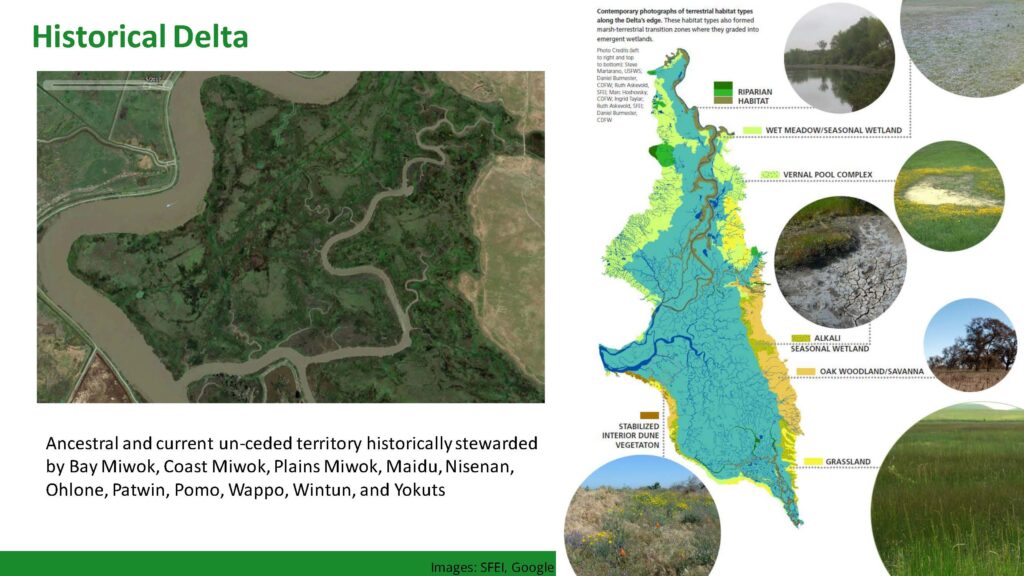

The Delta has been dramatically altered from its historic state after the lands were reclaimed for agriculture. The map on the slide below is from the San Francisco Estuary Institute; it shows how the Delta likely looked like pre-European colonization. At the time, most of the Delta was freshwater emergent wetlands where water flowed in and out daily from the tides and the rivers.

The Delta is the ancestral territory that was historically stewarded by Bay Miwok, Coast Miwok, Plains Miwok, Maidu, Nisenan, Ohlone, Patwin, Pomo, Wappo, Wintu, and Yokut peoples. Dr. Chapelle pointed out that not only has there been a complete change in the ecosystems in the Delta, but also a complete change in how the lands were managed.

The Delta is the ancestral territory that was historically stewarded by Bay Miwok, Coast Miwok, Plains Miwok, Maidu, Nisenan, Ohlone, Patwin, Pomo, Wappo, Wintu, and Yokut peoples. Dr. Chapelle pointed out that not only has there been a complete change in the ecosystems in the Delta, but also a complete change in how the lands were managed.

The map on the left is the map of the historical Delta from the previous slide, and the map in the middle shows the modern Delta; the main land use now is for agriculture.

“We’ve transitioned from a system dominated by freshwater wetlands into a system where water is prevented from interacting directly with the land by levees, and the land use is mostly in agricultural and other related land uses,” said Dr. Chapple. “This has reduced the freshwater wetlands that once comprised the majority of land cover in the Delta. So our challenge for thinking about the coequal goal of maintaining a healthy Delta ecosystem is how to achieve some measure of the ecosystem functions that would have historically been on the landscape in the context of a system that’s been radically changed and will never likely support the full range of ecosystems that we would have historically seen.”

These changes have impacted species, so benefits to the many state and federally-listed species are the main motivation for habitat restoration in the Delta. “So when we’re thinking about the ecosystem functions, a big part of it is supporting these and literally hundreds of other species that call the Delta home still, even in these even in these heavily altered conditions,” he said.

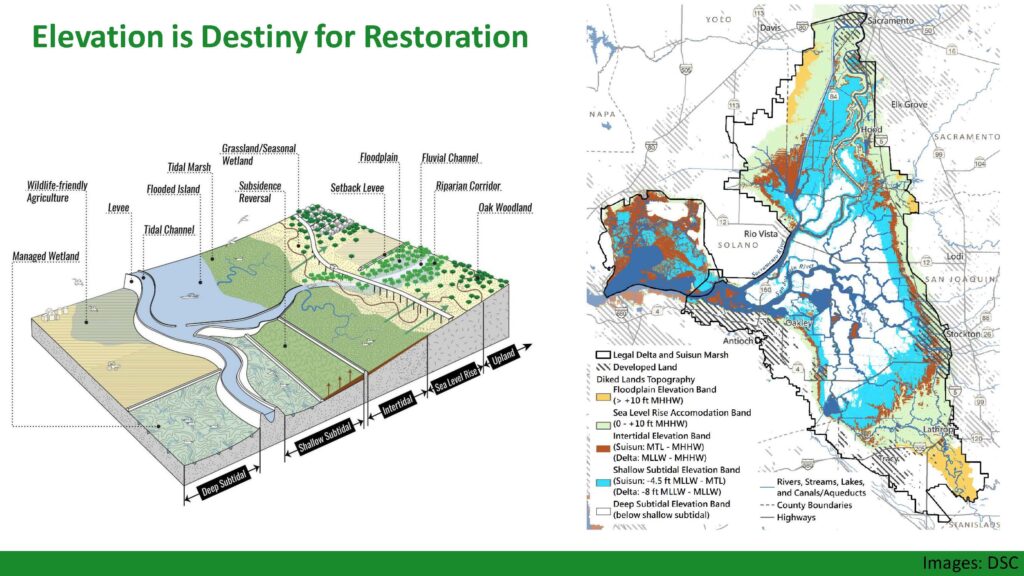

A key factor in siting restoration projects in the Delta is elevation. The figure on the left of the slide shows the different elevations in the Delta. There are deep subtidal areas up to 25 feet below sea level, shallow subtidal areas somewhat below sea level, intertidal areas at about mean sea level that could support tidal wetlands, a sea level rise accommodation band, and upland areas.

The map on the above right illustrates where the different elevations map across the actual landscape of the Delta and Suisun Marsh. The areas in white are the heavily subsided areas, lighter blue is moderately subsided, brown is intertidal, and light green is the sea level rise accommodation band.

Performance measures

There are three performance measures associated with specific ecosystem types:

Tidal Wetlands

The target for tidal wetlands is 32,500 acres. These wetlands are inundated daily by a combination of tides and flows from river channels. Examples of tidal wetland restoration are the Broadmoor Island Restoration Project and the Dutch Slough Restoration Project. This is important habitat for Delta smelt, Chinook salmon, and many other species. These projects are constructed in the intertidal elevation zone.

The target for tidal wetlands is 32,500 acres. These wetlands are inundated daily by a combination of tides and flows from river channels. Examples of tidal wetland restoration are the Broadmoor Island Restoration Project and the Dutch Slough Restoration Project. This is important habitat for Delta smelt, Chinook salmon, and many other species. These projects are constructed in the intertidal elevation zone.

Non-Tidal Wetlands

The target for non-tidal wetlands is 19,500 acres. Non-tidal wetlands have no direct connections to rivers or tides. Most non-tidal wetlands are projects designed for reversing subsidence in deeply subsided areas, such as the Mayberry Wetland Project and the Whale’s Mouth Wetland Project, both projects on Sherman Island. However, shallower subtidal areas can also be used for this type of restoration. In addition, non-tidal wetlands provide habitat for migratory birds, river otters, and several other species.

The target for non-tidal wetlands is 19,500 acres. Non-tidal wetlands have no direct connections to rivers or tides. Most non-tidal wetlands are projects designed for reversing subsidence in deeply subsided areas, such as the Mayberry Wetland Project and the Whale’s Mouth Wetland Project, both projects on Sherman Island. However, shallower subtidal areas can also be used for this type of restoration. In addition, non-tidal wetlands provide habitat for migratory birds, river otters, and several other species.

Riparian and floodplain restoration

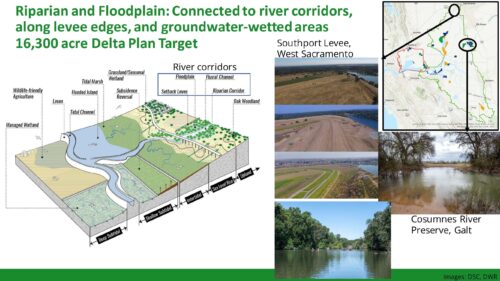

The target for riparian and floodplain restoration areas is 16,300 acres. These areas are generally connected to river corridors and are found along the edges of levees, although Dr. Chapple noted that in the Delta, there could be riparian-type vegetation in areas protected by levees because of groundwater seeping up in those areas. Example projects include the Southport Levee Project in West Sacramento, as well as numerous projects in the Cosumnes River Preserve and surrounding areas down I-5 in Galt.

The target for riparian and floodplain restoration areas is 16,300 acres. These areas are generally connected to river corridors and are found along the edges of levees, although Dr. Chapple noted that in the Delta, there could be riparian-type vegetation in areas protected by levees because of groundwater seeping up in those areas. Example projects include the Southport Levee Project in West Sacramento, as well as numerous projects in the Cosumnes River Preserve and surrounding areas down I-5 in Galt.

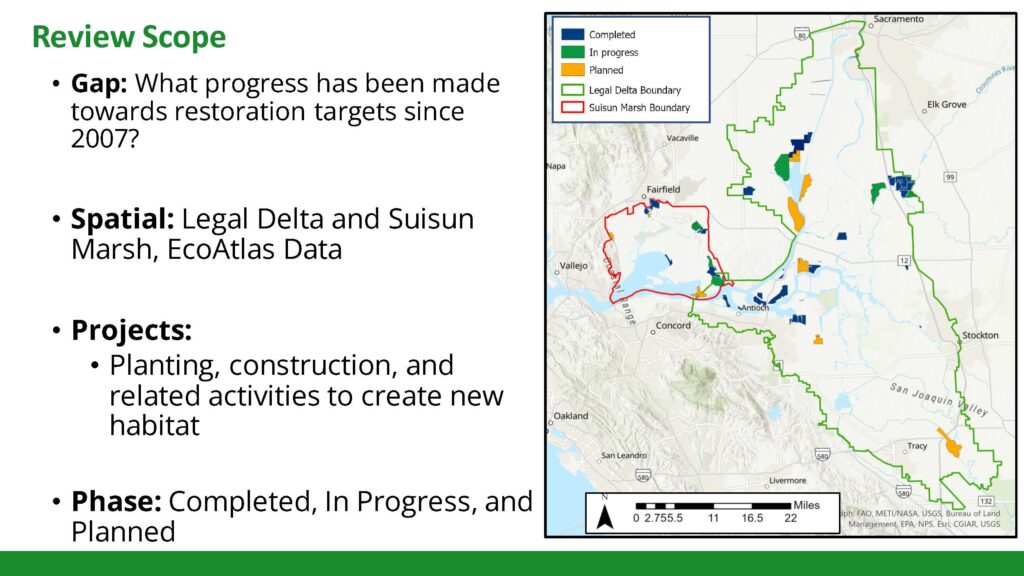

The scope of the review

To answer the question of what progress has been made towards the targets since 2007, they first set a spatial boundary of the legal Delta and Suisun Marsh to reflect the jurisdiction outlined in the Delta Plan. Then they built on data from the EcoAtlas website, an online project repository maintained by the San Francisco Estuary Institute, where people upload information about their restoration projects.

For their analysis, they included projects that involved active planting, construction, or other activities to create new habitats; they excluded projects where an existing ecosystem was preserved but not altered to improve habitat conditions. Completed projects are shown in blue, projects under construction in green, and planned projects in orange. He noted that since planned projects are not underway, some of the numbers for planned projects are subject to change.

Progress toward restoration targets

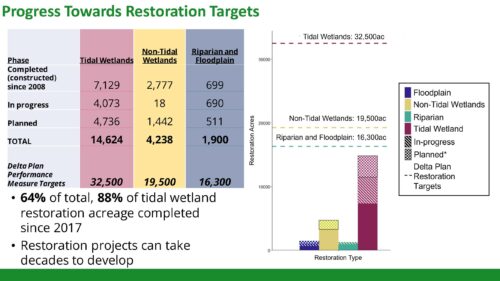

The table on the slide shows the progress since 2007: 14,625 acres of tidal wetlands toward the 32,500-acre target; 4238 acres of non-tidal wetlands towards the 19,500-acre target; and 1900 acres of riparian and floodplain ecosystems towards the 16,300-acre target.

The table on the slide shows the progress since 2007: 14,625 acres of tidal wetlands toward the 32,500-acre target; 4238 acres of non-tidal wetlands towards the 19,500-acre target; and 1900 acres of riparian and floodplain ecosystems towards the 16,300-acre target.

Dr. Chapple noted that 64% of the total projects on the list and 88% of the tidal wetland projects have occurred since 2017, so they are relatively new on the landscape; restoration projects can take many decades to develop the functions that they are designed to provide.

These projects have occurred for many reasons:

These projects have occurred for many reasons:

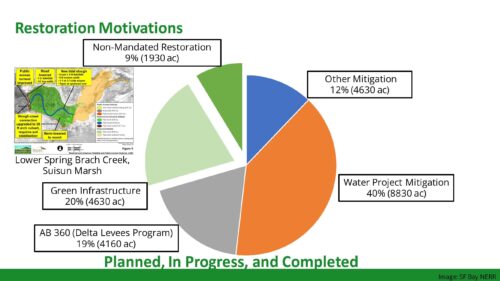

- Mitigation for the state and federal water projects comprises about 40% of the total acres that are planned, in progress, or completed, such as Lookout Slough and Cache Slough;

- Projects performed by the DWR Delta levees program to fulfill requirements under AB 360 at 19%, such as the Dutch Slough Tidal Wetland Restoration Project;

- Other mitigation projects comprise about 12%, which includes the Southport levee setback project in West Sacramento;

- Green infrastructure at 20% of the total are projects that address infrastructure and habitat needs together. Most of the acreage comes from the combination of completed and planned projects at the Montezuma Wetlands in Suisun Marsh, which takes dredged materials from the Port of Oakland and uses that material to create new wetlands.

- Non-mandated restoration projects are purely for ecological benefit and uplift and are not intended as mitigation or to fulfill a regulatory requirement. This is the smallest category at just 9% of the projects.

In conclusion …

The results of this study are being integrated into existing efforts. The numbers will be used in determining the progress of the performance targets set in chapter 4 and inform the work of the DPIIC Restoration Subcommittee. The results can also inform system-level ecosystem restoration adaptive management as the Delta Plan requires.

“It gives us a sense of what’s happening at the landscape scale,” said Dr. Chapple. “The information critical for helping inform decisions that different agencies are making moving forward as far as where, when and how they restore lands.”

The results also inform the Delta Adapts adaptation strategy, particularly the scenarios that are planned for the ecosystem. The results will also be the subject of a research paper.

“These numbers will change, and as they change, they’ll be updated in the Delta Plan restoration performance measures on the website and through the tracker that will provide a running total, building on these results that I presented today.”

Discussion

Chair Virginia Madueno noted that the greatest percentage was in tidal wetlands restoration, but there’s room to grow with non-tidal wetlands, riparian, and floodplain restoration.

Dr. Chapple agreed and said it’s helpful to have numbers around to illustrate that fact. However, he noted that there is a limitation with using the legal Delta boundary, which is also the jurisdiction of the Delta Plan. Some projects, such as the Big Notch project at the top of the Yolo Bypass and the Lower Elkhorn Basin project, are occurring just outside the legal Delta but will have substantial positive effects on the Delta.

“That’s something to consider as we move forward is thinking about how we incorporate projects that exist just outside the boundaries of the legal Delta but nonetheless have major implications for the ecological health of the Delta. If we were to include some of those projects, those numbers would increase.”

Dr. Chapple also pointed out that the majority of that tidal wetland acreage has happened because of the mitigation required for the operation of the state and federal water projects. “So those have a really strong stick, essentially, for why they have to happen. And those are based on the biological opinions initially consulted in 2008 for delta smelt in 2009 for salmon, so it’s one of the reasons we have seen an acceleration of those habitat types.”