At the November meeting of Metropolitan’s Imported Water Committee, agenda items included the second of a two-part presentation on the Delta Conveyance Project draft environmental impact report (EIR) and a presentation on a collaborative effort to restore salmonids in the Central Valley.

Delta Conveyance Project draft EIR, part 2

The Delta Conveyance Project is the latest iteration of a controversial project to divert water in the North Delta and route it through a tunnel under the Delta to existing infrastructure in the South Delta, rather than through the Delta’s leveed channels. (This project or some version of it has been discussed for decades.) The public review period for the draft environmental impact report ends on December 16.

At the October committee meeting, the staff gave the first of a two-part presentation on the draft EIR for the Delta Conveyance Project. That update included water supply reliability and resiliency and how the Delta Conveyance Project and the State Water Project relate to Metropolitan’s One Water vision. You can read coverage by clicking here.

This presentation included in-Delta engagement during the development of the draft EIR, tribal cultural resources, environmental justice, and the community benefits framework and program.

“The Delta Conveyance Project helps ensure that the State Water Project is more resilient to climate change, sea level rise, floods, and seismic events,” said Dee Bradshaw, Program Manager. “The flexibility provided will allow the updated State Water Project the ability to capture, move, and stormwater by making the most of big but infrequent storm events.”

“The Delta Conveyance Project helps ensure that the State Water Project is more resilient to climate change, sea level rise, floods, and seismic events,” said Dee Bradshaw, Program Manager. “The flexibility provided will allow the updated State Water Project the ability to capture, move, and stormwater by making the most of big but infrequent storm events.”

“Specifically, operating the proposed North Delta intakes would facilitate the capture of inflow when changing precipitation patterns are expected to generate higher inflow than the current April to June timeframe. That’s normally when reservoirs have historically captured runoff. By being able to capture inflow when it’s available, overall exports would be more reliable than with the existing South Delta pumps alone.”

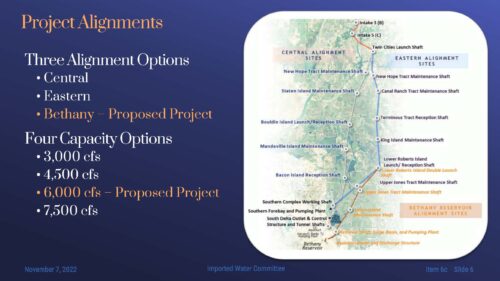

The proposed project is the Bethany alternative, which includes two intakes diverting 6000 CFS via a single tunnel along the eastern corridor and into the existing Bethany Reservoir.

Stakeholder Engagement Committee

The Stakeholder Engagement Committee was established by the Delta Conveyance Design and Construction Joint Powers Authority Board of Directors in October 2019. The Stakeholder Engagement Committee was designed to create a forum where members of the public, designated committee members, and the DCA technical teams could exchange technical and community-based information. With early design phase input from the Stakeholder Engagement Committee, DCA engineers were able to identify several design and logistics strategies to avoid and/or minimize potential construction effects on the local Delta community.

The Stakeholder Engagement Committee was comprised of 18 members representing agriculture, recreation, sportfishing, terrestrial and aquatic species, environmental justice, local business from the north and the south Delta, Delta history and heritage, tribal governments, Delta water districts, and county officials. Two members of the DCA board of directors acted as Chair and Vice Chair. The Stakeholder Engagement Committee completed its early design involvement and formally disbanded in January of this year.

The Stakeholder Engagement Committee was comprised of 18 members representing agriculture, recreation, sportfishing, terrestrial and aquatic species, environmental justice, local business from the north and the south Delta, Delta history and heritage, tribal governments, Delta water districts, and county officials. Two members of the DCA board of directors acted as Chair and Vice Chair. The Stakeholder Engagement Committee completed its early design involvement and formally disbanded in January of this year.

Ms. Bradshaw noted that Stakeholder Engagement Committee feedback led to changes in the design and location of key features, such as the removal of barge landings to avoid effects on Delta, recreational boaters, and traffic; changes to construction siting to minimize noise and reduce adverse effects on sandhill cranes and other migratory birds; avoiding the use of levee roads for heavy construction traffic to reduce potential impacts to levees; and the relocation and elimination of shaft sites due to traffic congestion concerns on local roads and highways.

Tribal cultural resources

After the Notice of Preparation release in 2020, DWR initiated tribal consultation with interested California tribes by sending letters to 121 tribes with potential affiliation to the project area, including the proposed project footprint areas upstream of the Delta and the State Water Project service areas. DWR is currently consulting with 13 tribes under CEQA, DWR’s tribal cultural engagement policy, and the incorporated California Natural Resources Agency Consultation Policy. DWR initiated a robust process to gather information needed to support tribal cultural resource determinations for the EIR.

“DWR recognized the importance of tribal expertise when identifying and evaluating potential tribal cultural resources, and has been working to incorporate that expertise regarding California tribes, histories and cultures and the importance and significance of resources from the tribes perspective,” said Ms. Bradshaw, noting that in addition to the formal government to government tribal consultation, DWR meets regularly and as requested with tribes.

“DWR recognized the importance of tribal expertise when identifying and evaluating potential tribal cultural resources, and has been working to incorporate that expertise regarding California tribes, histories and cultures and the importance and significance of resources from the tribes perspective,” said Ms. Bradshaw, noting that in addition to the formal government to government tribal consultation, DWR meets regularly and as requested with tribes.

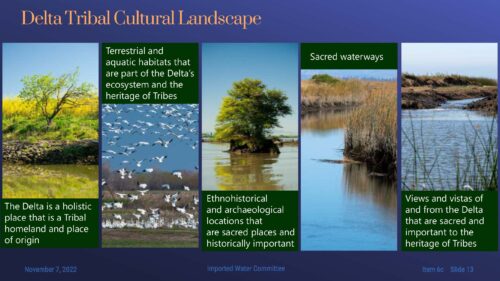

Chapter 32 of the draft EIR on tribal cultural resources considers the Delta a tribal cultural landscape with categories of character-defining features that are part of the whole landscape. The tribal cultural resources chapter analyzed impacts that could result from the construction, operation, and maintenance of the proposed project and project alternatives and proposes mitigation measures under CEQA to reduce the effects of any potentially significant impacts.

“The Delta tribal cultural landscape is currently the only tribal cultural resource being analyzed in the EIR,” said Ms. Bradshaw. “However, DWR included a process in the chapter to consider and evaluate additional information received after publication of the draft EIR and is continuing to consult with affiliated tribes to obtain additional input on mitigation measures under CEQA and the tribal Cultural Resources Management Plan.”

Ms. Bradshaw noted that DWR determined that the Delta is a cultural landscape with cultural value to California tribes affiliated with the Delta and that it could be geographically defined in terms of size and scope. DWR concluded that the Delta tribal cultural landscape is eligible for inclusion in the California Register of Historical Resources.

The Delta tribal cultural landscape is analyzed in the EIR as a tribal cultural resource to determine whether the project will have significant impacts. Impacts identified include those with the potential to materially impair a consulting tribe’s ability to physically, spiritually, or ceremonially experience each of the character-defining features of the Delta tribal cultural landscape. Character-defined features of the Delta tribal cultural landscape include the Delta as a holistic place that is a tribal homeland and place of origin; terrestrial and aquatic, plant and animal species and habitats that are part of the Delta’s ecosystem; and the heritage of California tribes, known historical and archaeological locations that are sacred places, and historically important sacred waterways, importantly, the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and views and vistas of and from the Delta, that are sacred and important to the heritage of California tribes.

The Delta tribal cultural landscape is analyzed in the EIR as a tribal cultural resource to determine whether the project will have significant impacts. Impacts identified include those with the potential to materially impair a consulting tribe’s ability to physically, spiritually, or ceremonially experience each of the character-defining features of the Delta tribal cultural landscape. Character-defined features of the Delta tribal cultural landscape include the Delta as a holistic place that is a tribal homeland and place of origin; terrestrial and aquatic, plant and animal species and habitats that are part of the Delta’s ecosystem; and the heritage of California tribes, known historical and archaeological locations that are sacred places, and historically important sacred waterways, importantly, the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and views and vistas of and from the Delta, that are sacred and important to the heritage of California tribes.

CEQA mitigation measures have been identified to avoid and minimize impacts on tribal cultural resources. Some key commitments identified include tribal preconstruction surveys for all ground-disturbing activities, tribal monitoring of all ground-disturbing construction activities, and setting aside land designated to relocate ancestral remains, cultural artifacts, and associated burial items that may potentially be encountered. This land designation, including access rights, would be permanent, and tribal involvement in restoration planning efforts and access to designated spaces in the restored areas for ceremonial purposes in perpetuity.

Environmental justice

Program Manager Jen Nevills then discussed how environmental justice is incorporated into the EIR.

The environmental justice analysis is included in the draft EIR to fulfill the requirements of NEPA and to provide consistency with the draft EIS being prepared by the Army Corps. It’s one of the few elements required by NEPA that’s not required under CEQA. The study analysis was also done considering state and California natural resources agency policies, which call for the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people concerning the development, adoption, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

The environmental justice analysis is included in the draft EIR to fulfill the requirements of NEPA and to provide consistency with the draft EIS being prepared by the Army Corps. It’s one of the few elements required by NEPA that’s not required under CEQA. The study analysis was also done considering state and California natural resources agency policies, which call for the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people concerning the development, adoption, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

To best serve the environmental review process, DWR developed and executed a robust outreach program to ensure the participation of disadvantaged communities and environmental justice organizations in the scoping process. DWR outreach strategy included notifications, scoping meetings, and comment workshops focused on gathering input from environmental justice communities. In addition, DWR conducted an environmental justice community survey.

The analysis in the draft EIR can be broken down into three main steps:

- First, DWR identified the study area, which consists of census tracts intersected by the footprint of the project, in which temporary or permanent effects of the project may occur.

- Second, DWR identified minority and low-income populations in the study area based on data from the US Census Bureau.

- And finally, resource areas where DWR concluded it could not mitigate impacts to a less than significant level were evaluated under all alternatives, including the no project alternative, to see if they resulted in disproportionate impacts on environmental justice communities.

Many of the impacts in the resource areas are associated with construction, such as noise, vibration, and traffic, and some are more permanent, such as the loss of agricultural lands. All of them are triggers where mitigation would be implemented but could not reach a less than significant level.

“The analysis concluded that while there are impacts in the study area that cannot be fully mitigated, they do not disproportionally impact environmental justice communities,” said Ms. Nevills. “I will note that DWR also looked at a few other important areas that didn’t have CEQA impact conclusions, such as water supply, socioeconomics, and climate change. This look included a discussion of indirect effects on the State Water Project export service areas and DWR, in that analysis, identified that at least two-thirds of the population in the export service areas meet the definition of disadvantaged or severely disadvantaged communities based on being classified as minority and/or based on income.”

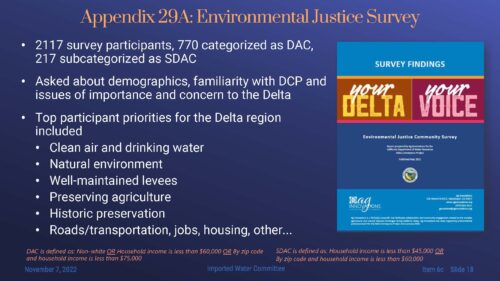

An environmental justice survey was conducted to gather input from disadvantaged communities in the Delta region about how they work, live, recreate and experience the Delta, and to focus on communities that are historically burdened and underrepresented people of color, and low-income communities of interest, including indigenous and tribal interests. Over 2100 participants completed the survey; of that number, 770 were categorized as members of disadvantaged communities, and 217 of those 770 were further subcategorized as severely disadvantaged.

An environmental justice survey was conducted to gather input from disadvantaged communities in the Delta region about how they work, live, recreate and experience the Delta, and to focus on communities that are historically burdened and underrepresented people of color, and low-income communities of interest, including indigenous and tribal interests. Over 2100 participants completed the survey; of that number, 770 were categorized as members of disadvantaged communities, and 217 of those 770 were further subcategorized as severely disadvantaged.

Survey questions collected information on demographics, familiarity with the Delta Conveyance Project, and topics of importance and concern relative to the Delta. The full survey results are included in Appendix 29A to the draft EIR. The top important concerns and priorities were clean air and water, the natural environment, levees, agriculture, and historic and cultural preservation. Other priorities were infrastructure and economics.

Survey results were used to inform the environmental justice analysis and the development of a community benefits program.

Community benefits program

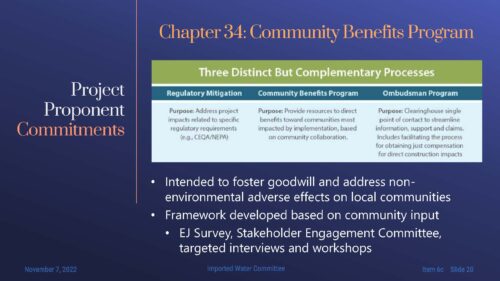

The community benefits program is one of three distinct but complementary processes intended to address effects within the local Delta communities. The others are regulatory mitigation, which addresses impacts related to CEQA requirements, and an ombudsman program, which would address claims and compensation directly related to construction impacts.

“The community benefits program is anticipated to be a set of commitments made by project proponents and created in coordination with the local community to address local effects that may occur as a result of the Delta conveyance project,” said Ms. Nevills. “These commitments are intended to go beyond traditional environmental mitigation to foster goodwill and address the adverse effects local communities may encounter during the long construction period.”

“The community benefits program is anticipated to be a set of commitments made by project proponents and created in coordination with the local community to address local effects that may occur as a result of the Delta conveyance project,” said Ms. Nevills. “These commitments are intended to go beyond traditional environmental mitigation to foster goodwill and address the adverse effects local communities may encounter during the long construction period.”

The community benefits program frameworks described in Appendix 3g includes two major categories of benefits:

The Delta community fund would be managed by the community to pay for projects and programs related to water, air quality, public safety, recreation, habitat, and others.

An Economic Development and Integrated Benefits Program includes benefits such as economic development benefits accomplished through targeted hiring programs and business participation programs. Other benefits could be ‘leave behinds’ that repurpose and leave behind certain construction-related project features for the community, community centers and education programs, recreation facilities, roads, connections to reliable internet service, and emergency response facilities.

Ms. Nevills noted that the development of the community benefits program is an ongoing process, and no decisions will be made, no agreements finalized, and no commitments implied, including funding, until completion of CEQA review and DWR’s approval of the proposed project.

She concluded by noting that the deadline for submitting comments is December 16.

Bay Delta: Metropolitan participates in a collaborative salmon restoration project

Allison Collins, a senior resource specialist with Bay-Delta Initiatives, gave a presentation on a collaborative salmonid recovery project in which Metropolitan participates. The project goal is to develop an effective and implementable strategy to recover listed and non-listed salmonids broadly while considering other ecological, social, and economic interests in the region.

“We’re doing this because salmon populations are not doing well, and this has significant socio-economic impacts to a broad range of communities,” said Ms. Collins.

The idea for this project evolved from the Collaborative Science and Adaptive Management Program (CSAMP), a collaborative forum that addresses water operations and listed fish species issues. The group has long focused on Delta operations but has recognized the need to consider salmon recovery in a broader context.

“We recognize that salmon exists in freshwater, estuarine Delta, and ocean environments and that many different organizations impact salmonids along the way, and we’re all kind of doing work together to try to further this goal,” said Ms. Collins.

To put a strategy in place, a planning team was convened to lead the vision. The group is comprised of folks from Trout Unlimited, the Bay Institute, Valley Water, Metropolitan, and many consultants.

To put a strategy in place, a planning team was convened to lead the vision. The group is comprised of folks from Trout Unlimited, the Bay Institute, Valley Water, Metropolitan, and many consultants.

Acknowledging the numerous initiatives being implemented to promote salmon recovery and not wanting to duplicate efforts, the planning team sought to develop a process to bring together the various efforts to advance salmonid recovery to discuss how they can work together to advance salmonid recovery and leverage resources.

To develop measurable recovery targets, they first had to define what it means to recover salmonids broadly. Ms. Collins reminded that the focus is on the entire lifecycle from the freshwater to the ocean. They are using multiple models and analytical tools to evaluate and develop scenarios that could achieve salmonid recovery, considering all regional projects. And they are striving for a broad, equitable, and transparent engagement process, bringing together water agencies, farming communities, fishermen, tribal governments, and others.

There are three phases to the project:

There are three phases to the project:

Phase One began in 2021 and was funded by the State Water Contractors and focused on defining what it means to recover salmonids.

Phase Two, in process for most of 2022, solicited input from interested parties throughout the Central Valley to understand why people care about salmon and what kind of projects are being implemented.

Phase Three will begin in December. This phase will focus on the decision support system. They are using participant input to model baseline and benchmark scenarios with a structured process that allows different scenarios to be evaluated while considering the social, economic, and ecological interests. The project aims to identify a suite of actions that could be implemented to achieve salmon recovery while considering all the interests.

Phase One: Recovery framework

A series of 12 workshops were held to discuss what it meant to recover salmonids in a broad sense. There were discussions around why folks care about salmon, what it means to see salmon recovered, and how that goes above and beyond being listed, which focuses on avoiding jeopardy or extinction of the species.

Key principles for defining the framework include focusing on viable salmon populations that aren’t tied to regulatory or policy processes; distinguishing between natural and hatchery origin; and tracking both listed and non-listed salmonids.

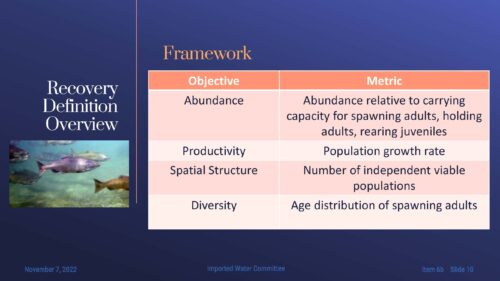

The slide shows the framework and an example metric for each objective. The metrics define salmonid recovery and evaluate how those objectives can be achieved under different scenarios.

The slide shows the framework and an example metric for each objective. The metrics define salmonid recovery and evaluate how those objectives can be achieved under different scenarios.

The first objective for viable salmon populations is abundance, or how many fish there are; it can be measured by considering abundance relative to carrying capacity for different life stages. Ms. Collins explained that a certain stretch of river has a given amount of habitat capable of supporting a certain number of fish, so it can be calculated how many fish are there, given the carrying capacity of a river’s section.

The productivity objective can be measured by how many babies each adult can produce, such as by measuring the population growth rate.

The objective for spatial structure is about where the fish are on the landscape. Based on historic data and future conditions, the team has identified many independent variable populations they think the Central Valley can support in both the Sacramento and San Joaquin basins.

The last objective is diversity, including genetic and life history diversity. One way to measure that is to look at the age distribution of spawning adults; ideally, there should be young fish and some older adults contributing to the population.

Phase Two: Outreach

Phase one focused on defining what it means to recover salmonids; Phase Two then worked to define what this means with respect to other social, ecological and cultural interests.

Phase one focused on defining what it means to recover salmonids; Phase Two then worked to define what this means with respect to other social, ecological and cultural interests.

In early 2022, a series of outreach webinars was held with multiple organizations to hear from other interests about what projects they were doing and why they care about salmonids. The webinars were focused on values, asking what people’s perspectives and values were related to salmonid recovery.

A June workshop had 105 participants from 60 organizations, including four tribal nations, NGOs, state and federal agencies, universities, and agricultural entities. The workshop focused on questions such as, how do you think salmonid recovery might benefit you? How do you think efforts to achieve salmonid recovery might negatively impact you? And what are the unique factors in your watershed that act as barriers to salmonid recovery?

The idea is that just as the first phase defined what it means to recover salmon, they now needed to define what salmon recovery means for other interests and add those social, cultural, and economic interests.

The idea is that just as the first phase defined what it means to recover salmon, they now needed to define what salmon recovery means for other interests and add those social, cultural, and economic interests.

A small sample of the over 500 value statements collected is shown on the slide. After the workshop, they identified whether the statement was process-based or decision-based. An example would be climate change adaptation; climate change informs the process where they are going, but it doesn’t necessarily help decide which restoration action to implement to recover salmonids.

“More people employed in salmonid-related jobs is something we could measure,” said Ms. Collins. “So we can calculate now how many people are employed in salmonid-related jobs. We could identify different scenarios to recover salmonids and then look at how that impacts the number of people employed in that job. So we’ve been trying to distill these value statements into kind of measurable objectives that are both process and decision-based.”

They also asked participants how many salmonids were produced in their system and what habitat they thought was available to restore in their watershed. They also wanted to understand what is currently planned and going on to aid salmonid recovery. With the Department of Fish and Wildlife’s help, they cataloged over 200 projects that are now ongoing or planned.

“This can be used as a starting basis for what actions are out there to recover salmonids and can help us define where we want to go,” said Ms. Collins.

Phase Three: Decision support

Phase three starts in December. This phase is the decision support phase, which builds on the information developed in both of the previous phases. A series of workshops are planned in December to bring previous participants and others to update them and show them their work.

2023 will focus on identifying the actions to implement to recover salmonids and estimating the consequences of those actions on salmonids and other interests. This will compare the different actions’ trade-offs and allow stakeholders and other users to discuss how implementing action A over action B impacts everyone.

This work will culminate in March 2024 with a strategy to achieve a broad recovery that considers other social, ecological, and economic interests.

Why this work is important to Metropolitan

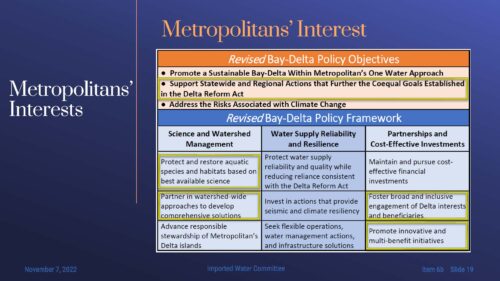

Ms. Collins then explained why this work is important to Metropolitan’s interests. “This project is closely related to our revised Delta policy objectives,” she said. “It’s related to our policy objective to support statewide and regional actions that further the coequal goals established in the Delta Reform Act. So this project is trying to identify, what good can we do to cover someone is but considering those other really important interests that we have in the region.”

Ms. Collins then explained why this work is important to Metropolitan’s interests. “This project is closely related to our revised Delta policy objectives,” she said. “It’s related to our policy objective to support statewide and regional actions that further the coequal goals established in the Delta Reform Act. So this project is trying to identify, what good can we do to cover someone is but considering those other really important interests that we have in the region.”

Another objective is to protect and restore aquatic species and habitats based on the best available science and to partner in watershed-wide approaches to develop comprehensive solutions. “With this project, we’re really trying to merge that hard science of what we know about salmonids and the actions we can do to benefit them, with kind of this partnership approach, understanding that salmon touch a lot of people and we need all these people to be there to tell us why they care about salmon, how salmon impacts them. And if we implement different actions, how are they going to be affected.”

Another policy objective is to foster broad and inclusive engagement of Delta interests and beneficiaries and promote innovative and multi-benefit initiatives. “This project is really ambitious in bringing interested parties together to have these conversations. I have 18 years of experience in salmonid ecology. And I haven’t participated in a process that brings so many people together to have conversations about why we care about fish, the things we can do, and the trade-offs that exist. So this is an innovative project that is fostering engagement and being inclusive, and not just of Delta interests, but of Central Valley interests.”

Conclusion

“Species listed under the Endangered Species Act really do limit our water supply reliability,” said Ms. Collins. “This project is working to identify priority actions that can recover salmonids that are agreed upon by this multi-user group. We have all these different parties at the table, and at our values workshops, we had over 60 Different organizations participating.”

“What we’re going to come up with at the end is a list of projects that can be implemented to recover salmonids that consider these other important values. And from that, Metropolitan and any other agency can look at this list and identify what actions best fit our mission, what we can best aid, and how we can best partner with everyone to implement actions to benefit the species as we move forward.”