October Council meeting features Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot and Metropolitan Water District General Manager Adel Hagekhalil

Reduced reliance on the Delta; it’s the state’s policy and one of the regulations embodied in the Delta Stewardship Council’s Delta Plan. But are we making progress? At the October meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, Natural Resources Secretary Wade Crowfoot and Southern California water leaders discussed efforts to improve regional water supplies, reduce reliance on the Delta, and increase climate resiliency.

Reduced reliance on the Delta – A state policy

Jeff Henderson, Deputy Executive Officer for Planning and Performance, gave some background on reduced reliance.

The concept of reduced reliance on the Delta is deeply embedded in the origins of the Council and the Delta Reform Act in the form of the coequal goals. The coequal goals are to achieve a more reliable water supply for California and to protect, restore, and enhance the Delta ecosystem; the coequal goals shall be accomplished in a manner that protects and enhances the unique cultural, recreational, natural resource, and agricultural values of the Delta as an evolving place.

The Delta Reform Act included objectives to advance the coequal goals, including managing the Delta’s water and environmental resources for the long term, promoting statewide water conservation and water use efficiency, improving the water conveyance system, and expanding statewide water storage. In addition, the Act established reduced reliance as a statewide policy, articulating that the state’s policy is to reduce reliance on the Delta and meet California’s future water supply needs through a statewide strategy of investing in improved regional supplies, conservation, and water use efficiency.

The Delta Reform Act included objectives to advance the coequal goals, including managing the Delta’s water and environmental resources for the long term, promoting statewide water conservation and water use efficiency, improving the water conveyance system, and expanding statewide water storage. In addition, the Act established reduced reliance as a statewide policy, articulating that the state’s policy is to reduce reliance on the Delta and meet California’s future water supply needs through a statewide strategy of investing in improved regional supplies, conservation, and water use efficiency.

The concept of reduced reliance on the Delta and improved regional self-reliance is reflected in the Delta Plan in several ways:

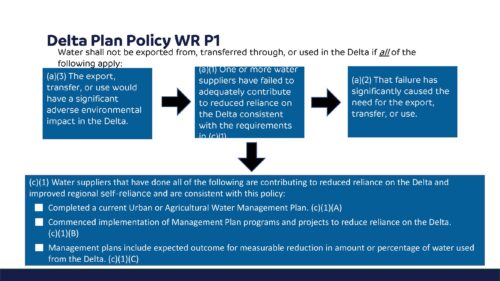

Regulatory policy WRP 1, which applies to covered actions, states that water shall not be exported from, transferred through, or used in the Delta if several conditions apply. These include excluding projects where one or more water suppliers have failed to adequately contribute to reduced reliance on the Delta consistent with the requirements of the Act and where that failure has significantly caused the need for the export, transfer, or use.

Regulatory policy WRP 1, which applies to covered actions, states that water shall not be exported from, transferred through, or used in the Delta if several conditions apply. These include excluding projects where one or more water suppliers have failed to adequately contribute to reduced reliance on the Delta consistent with the requirements of the Act and where that failure has significantly caused the need for the export, transfer, or use.

Another provision of the regulation establishes that water suppliers who would receive water from a covered action project must complete urban water management plans or agricultural water management plans, identify how the activities in those management plans are being implemented, and document the expected outcome for a measurable reduction in either the amount or percentage of water that’s used from the Delta by those suppliers.

The Delta Plan also has various recommendations that address urban water management plans, agricultural water management plans, and integrated water management plans with regard to providing a water supply reliability element. Council staff has been working with the Department of Water Resources to identify some example methodologies water suppliers might use to document reduced reliance.

The Delta Plan also has various recommendations that address urban water management plans, agricultural water management plans, and integrated water management plans with regard to providing a water supply reliability element. Council staff has been working with the Department of Water Resources to identify some example methodologies water suppliers might use to document reduced reliance.

The Delta Plan has four performance measures for reduced reliance: urban water use efficiency, alternative water supplies used by the various water suppliers, gauging water supply reliability, and agricultural water planning.

Newsom’s Water Supply Strategy

Secretary Wade Crowfoot addressed the Council, beginning by noting that he’s finishing a recently published history on early California, and it has him thinking about the evolution of places in California, especially the Delta. Pre-European contact, the Delta was an incredible estuary that would dry out in the summer, supporting native communities and mammals like grizzly bears, and then wet up in the winter and provide massive amounts of aquatic habitat. Then the Delta was settled, the wetlands were filled in, and the land turned into productive agricultural lands; the Delta became the highway between San Francisco and Sacramento. Fast forward to the mid-20th century, and the Delta became an important place for the conveyance of water, allowing the state to grow to 40 million people and the fourth largest economy in the world while providing a livelihood for communities and environmental habitat for one of the most biodiverse places in the world.

So the challenge, he said, is how do we meet all these goals? How do we restore ecological function, use the Delta as water infrastructure, and ensure Delta communities thrive? How do we ensure the continued function of the system but also reduce the reliance on the Delta?

So the challenge, he said, is how do we meet all these goals? How do we restore ecological function, use the Delta as water infrastructure, and ensure Delta communities thrive? How do we ensure the continued function of the system but also reduce the reliance on the Delta?

Climate change is fundamentally altering California’s hydrology. Climate scientists say the state will continue to experience intense droughts and intense flooding; the dry periods will be drier, and the wet periods will be wetter. As a result of hotter temperatures, scientists say that by 2040, California will lose about 10% of its water supply. Simply put, hotter temperatures mean less snowpack in the winter, and more of the precipitation that does fall will be absorbed into thirsty soils and plants and evaporate with the warmer temperatures. So in August, the Governor released his water supply strategy outlining actions to address the potential loss of water supply.

“One of those actions is supporting local water agencies and regional water agencies becoming more self-sufficient and diversified in their water supply and relying less on faraway rivers, be it the Colorado River, the Owens River, or the Sacramento and San Joaquin running through the Delta because we know that we will have a less reliable water situation, situation moving forward,” said Secretary Crowfoot.

The water supply strategy details specific actions that need to be taken by 2030-2040 to build resilience to the changing climate. It includes measures such as significantly improving water efficiency, eliminating water waste, expanding water recycling, recharging groundwater supplies, building new above-ground water storage where it makes sense, urban stormwater capture and use, and desalination.

The water supply strategy details specific actions that need to be taken by 2030-2040 to build resilience to the changing climate. It includes measures such as significantly improving water efficiency, eliminating water waste, expanding water recycling, recharging groundwater supplies, building new above-ground water storage where it makes sense, urban stormwater capture and use, and desalination.

Secretary Crowfoot said that a key component of the Governor’s hotter, drier strategy is ensuring resilient conveyance for movement of water, acknowledging that it’s a controversial topic for some stakeholders in the Delta.

“From our perspective, while we can reduce reliance on faraway rivers, we will not eliminate the need for our backbone water system in California,” he said. “It will still be necessary to move water from Northern California rivers to Southern California, but also the Bay Area. I remind our friends in the Bay Area that they also import water over 100 miles from parts of the Sierra Nevada. So it’s about diversifying supply, building local water resilience, and ensuring the resilience of the conveyance that we have.”

“We know that water conveyance, whether in the Delta or elsewhere, is subject to real challenges,” Secretary Crowfoot continued. “In some places, the ground has subsided or sunk, threatening infrastructure. In other parts like the Delta, we’re quite worried about the intrusion of saltwater into the southern and interior Delta and the continued concerns or threats of seismic activity and an earthquake. So you’ll hear today that leaders across California are committed to aligning with you on reducing the reliance on the use of the San Joaquin and Sacramento rivers. At the same time, we want to focus on ensuring that conveyance maintains viability in the future decades because California will need it.”

Presentation: Metropolitan Water District

Adel Hagekhalil is the General Manager of Metropolitan Water District, Southern California’s regional water supplier serving 19 million people across six counties and 5200 square miles. In his presentation, he emphasized how Southern California is working to create a balanced, holistic approach anchored in integration, innovation, and inclusion.

“We all have an interest and a duty to work together to create a future that is a balanced future for water in our state, in our region, and the Southwest,” he said.

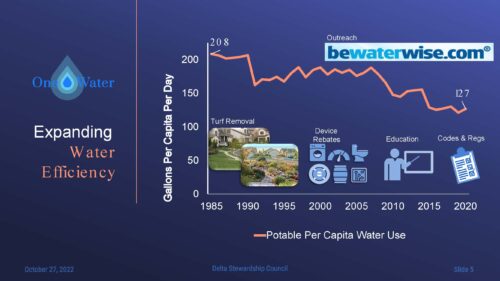

In Southern California, half of the water supplies are from the Los Angeles Aqueduct, local groundwater resources, water recycling, and desalination. Over the years, Metropolitan has invested $1.5 billion in conservation and local resource programs to encourage their member agencies to build a local supply, similar to what Orange County and San Diego have done. Metropolitan offers rebates for smart meters and has focused distribution of rebates for replacing toilets in apartment buildings in disadvantaged communities. These investments have paid off in Southern California as water efficiency has expanded; the region uses nearly half as much as in 1985, despite adding millions of residents.

In Southern California, half of the water supplies are from the Los Angeles Aqueduct, local groundwater resources, water recycling, and desalination. Over the years, Metropolitan has invested $1.5 billion in conservation and local resource programs to encourage their member agencies to build a local supply, similar to what Orange County and San Diego have done. Metropolitan offers rebates for smart meters and has focused distribution of rebates for replacing toilets in apartment buildings in disadvantaged communities. These investments have paid off in Southern California as water efficiency has expanded; the region uses nearly half as much as in 1985, despite adding millions of residents.

Metropolitan is also working to augment supply through water recycling, stormwater capture, and increasing storage. For example, Metropolitan is partnering with the Antelope Valley-East Kern Water Agency on a groundwater storage project in the Antelope Valley. In addition, some member agencies are considering desalination.

Most importantly, Metropolitan, in partnership with the LA SAN, is working on the Pure Water Southern California project, which would build a recycled water plant in Carson capable of recycling 150 million gallons per day. Arizona and Nevada are also partners on the project because it would lessen California’s draw on the Colorado River.

Most importantly, Metropolitan, in partnership with the LA SAN, is working on the Pure Water Southern California project, which would build a recycled water plant in Carson capable of recycling 150 million gallons per day. Arizona and Nevada are also partners on the project because it would lessen California’s draw on the Colorado River.

As for reducing reliance on the Delta, Mr. Hagekhalil noted that the Metropolitan Board recently adopted updated Bay-Delta Policies that explicitly state that Metropolitan will support statewide and regional actions that further the coequal goals established in the Delta Reform Act and protect water supply reliability and quality while reducing reliance on the Delta, consistent with the Delta Reform Act.

Climate change is changing the game, and major reductions are needed on the Colorado River. “The solution is not just a Southern California problem and a Southern California solution,” said Mr. Hagekhalil. “It’s a holistic solution. We need the legislators, the state, and the Governor to continue to invest because an investment in Southern California will help us all.”

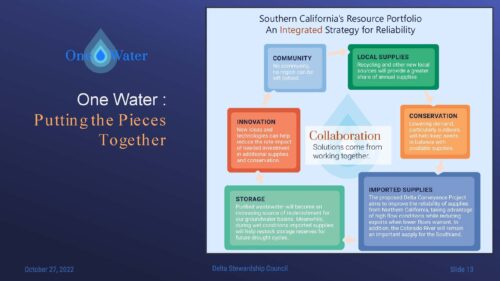

Metropolitan’s strategy is a “One Water” approach that includes potable reuse, stormwater recharge, groundwater storage, and sustainable use.

Metropolitan’s strategy is a “One Water” approach that includes potable reuse, stormwater recharge, groundwater storage, and sustainable use.

“The One Water vision is not just about water and holistic solution; it’s about people bringing people together and ensuring we have balanced solutions for the environment, farmers, communities, and urban users,” said Mr. Hagekhalil. “If we do it in a balanced approach, I think we all can win. We all can be under the same blue tent with no one left behind.”

“The solution is diversifying our water supply, recycling every drop, storing our water when we have high flows, and building infrastructure to move water around. Those are the solutions. And if we do it together in collaboration, I think we can solve all the challenges in our state, the Delta, and also around the Southwest.”

Presentation – LA SAN

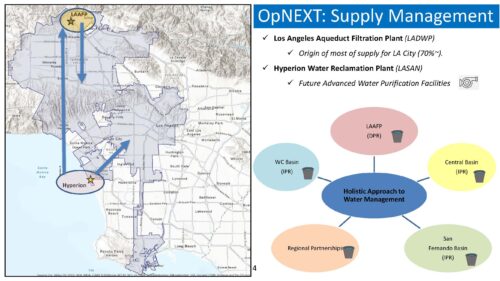

Barbara Romero is the Director and General Manager of LA Sanitation and Environment (or LA SAN). LA SAN protects public health and the environment by providing wastewater treatment, solid waste management, and stormwater management for 4.7 million customers across 600 square miles. LA SAN operates 6,700 miles of sewer lines and four wastewater treatment plants that process 300 million gallons of sewage per day.

LA SAN has a recycled water program that works in coordination with LA DWP. Three of the four treatment plants do recycle water; however, the Hyperion plant does not. Currently, 85% of the treated wastewater is discharged into Santa Monica Bay.

LA SAN has a recycled water program that works in coordination with LA DWP. Three of the four treatment plants do recycle water; however, the Hyperion plant does not. Currently, 85% of the treated wastewater is discharged into Santa Monica Bay.

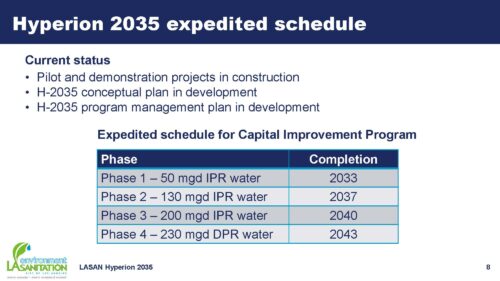

The goals of the Hyperion 2035 project are to produce 260,000 acre-feet per year of recycled water for potable reuse, modernize other plant processes at Hyperion, and reduce future effluent discharges into Santa Monica Bay. The project will generate 80,000 jobs during construction and create over 400 permanent jobs.

“The key part for Los Angeles is to keep it affordable,” said Ms. Romero. “Our investments in Los Angeles will reduce the impacts and pressures in this state and others … it frees up not only water for the region and state, but it also makes us more resilient in Los Angeles. I want you to know that we are committed to investing our own resources in Los Angeles. But we also need some support from the state. We’re asking for you to understand that this is something that we need to work on collectively; it’s going to cost us on the front end, but it’s going to reduce some of the pressures in the back end.”

“The key part for Los Angeles is to keep it affordable,” said Ms. Romero. “Our investments in Los Angeles will reduce the impacts and pressures in this state and others … it frees up not only water for the region and state, but it also makes us more resilient in Los Angeles. I want you to know that we are committed to investing our own resources in Los Angeles. But we also need some support from the state. We’re asking for you to understand that this is something that we need to work on collectively; it’s going to cost us on the front end, but it’s going to reduce some of the pressures in the back end.”

The hope is to complete the first phase in 2033, which would produce 50 million gallons per day of water for indirect potable reuse. However, they are looking at how they can accelerate the timeline. “Part of it is we need funding to move up those dates,” she said.

Presentation: Coachella Valley Water District

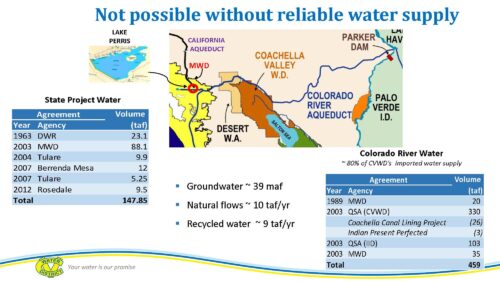

Robert Cheng is the Assistant General Manager of the Coachella Valley Water District, which serves a population of 270,000 across Riverside, Imperial & San Diego counties.

“Our area is really a land of contrasts,” he said. “We have some high locations of almost 11,000 feet all the way down to below sea level. We also experience a huge swing in temperatures.”

The average precipitation in the region is less than four inches, but nonetheless, they have sustained a large economy, including golf courses, tennis tournaments, and music festivals. Agriculture is a significant economic activity, producing between 750 million to a billion dollars in agricultural products. But none of this is possible without a reliable water supply, he said.

The average precipitation in the region is less than four inches, but nonetheless, they have sustained a large economy, including golf courses, tennis tournaments, and music festivals. Agriculture is a significant economic activity, producing between 750 million to a billion dollars in agricultural products. But none of this is possible without a reliable water supply, he said.

The groundwater basin has a natural yield of about 10,000 acre-feet a year, and they do recycle water. Still, to sustain the region’s robust economy, they depend on imported water supplies of about 600,000 acre-feet, although they usually don’t get that much.

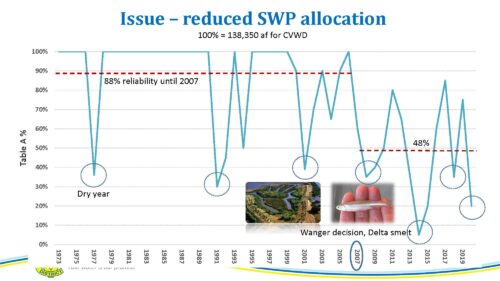

Mr. Cheng presented a slide showing the State Water Project allocation over the years. Although not directly connected to State Water Project infrastructure, the Coachella Valley Water District is a State Water Project contractor, receiving their water through an exchange agreement with Metropolitan Water District.

Mr. Cheng presented a slide showing the State Water Project allocation over the years. Although not directly connected to State Water Project infrastructure, the Coachella Valley Water District is a State Water Project contractor, receiving their water through an exchange agreement with Metropolitan Water District.

“I think this highlights the dramatic shift,” he said. “Delta water was about 90% reliable until essentially 2007. And then, after the Wanger decision in 2007, our reliability actually decreased to less than 50%. So we’re learning to live with less.”

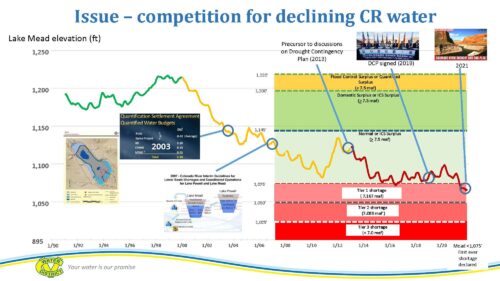

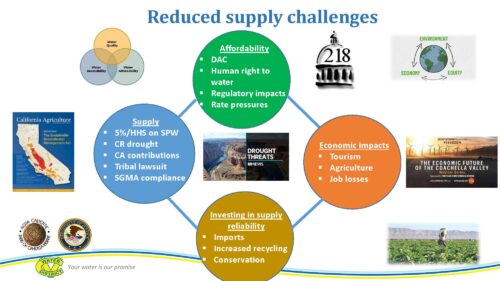

The slide summarizes the future uncertainties of the region’s water supply. They are committed to sharing up to 24,500 acre-feet of reductions of their Colorado River. Their State Water Project deliveries are down almost 90,000 acre-feet from their contracted amount. They have been looking at recycled water projects, but there are regulatory hurdles, and the cost element cannot be ignored.

The slide summarizes the future uncertainties of the region’s water supply. They are committed to sharing up to 24,500 acre-feet of reductions of their Colorado River. Their State Water Project deliveries are down almost 90,000 acre-feet from their contracted amount. They have been looking at recycled water projects, but there are regulatory hurdles, and the cost element cannot be ignored.

Conservation efforts focus on groundwater use and Colorado River use. They have implemented landscape plans and ordinances, smart controllers, and tiered rates, saving about 1.3 million acre-feet in the last ten years.

Colorado River supplies are used primarily by agriculture, and Coachella Valley farmers are highly efficient, using less than 3.8 acre-feet per acre per year. More than 60% of their customers have invested in drip irrigation. In addition, CVWD lined the Coachella Canal, saving up to 132,000 acre-feet per year that is transferred to other agencies. Agricultural water system losses are less than 6% due to a series of closed pipes and water meters.

The reduced water supply presents many challenges. Further reductions in Colorado River use will be needed. There is litigation with the Agua Caliente Tribe over groundwater; there is also compliance with SGMA. There are disadvantaged communities that tie back to the human right to water. Regulatory impacts from the increased pace of regulation rulemaking put pressure on all of us. These create economic impacts on tourism and agriculture, which, if not managed, could result in job losses.

The reduced water supply presents many challenges. Further reductions in Colorado River use will be needed. There is litigation with the Agua Caliente Tribe over groundwater; there is also compliance with SGMA. There are disadvantaged communities that tie back to the human right to water. Regulatory impacts from the increased pace of regulation rulemaking put pressure on all of us. These create economic impacts on tourism and agriculture, which, if not managed, could result in job losses.

In response, they are looking at fixing aging infrastructure for imported water, looking for opportunities to expand water recycling, and increasing agricultural and urban water conservation.

Under SB 535, 83 small water systems were identified that suffer from either lack of connection or water quality issues, primarily due to arsenic; it would take $72 million to address it. “Sometimes system consolidation is easy to talk about, but it’s very difficult to execute,” said Mr. Cheng. “We also face barriers from Proposition 218, which prevent using ratepayer funding for these projects. So we’re actively looking for grants.”

Council discussion

Council Chair Virginia Madueño asked Mr. Hagekhalil what other technologies are being explored and what funding mechanisms are available.

Mr. Hagekhalil said that Southern California first needs to expand water recycling and increase stormwater capture.

Voters have approved taxes to fund stormwater projects. One of those is the Rory M. Shaw Wetlands Park in Sun Valley. The nearby disadvantaged community suffered from poor air quality, lack of flood management, and degraded water quality in the river. So the project converted a former landfill into a wetlands park that mitigates flood risk and reduces stormwater pollution while increasing recreational opportunities and wildlife habitat. The treated stormwater is then used for groundwater recharge.

Mr. Hagekhalil also noted that the LA DWP is investing in the cleanup of groundwater basins. Many groundwater basins in Southern California are contaminated with salt, so they are also looking at brackish water treatment; brine management is the challenge. Also under consideration are lining canals, which can lose water due to seepage and evaporation; they are considering covering them with solar panels to generate electricity and reduce evaporative losses.

Mr. Hagekhalil also noted that the LA DWP is investing in the cleanup of groundwater basins. Many groundwater basins in Southern California are contaminated with salt, so they are also looking at brackish water treatment; brine management is the challenge. Also under consideration are lining canals, which can lose water due to seepage and evaporation; they are considering covering them with solar panels to generate electricity and reduce evaporative losses.

“Every drop, I think, is worth it,” said Mr. Hagekhalil. “I have a new office I created when I took over. It’s the Sustainability Resiliency Innovation Office. It’s a huge effort to look at everything we can do to ensure that we can manage the water in a smart way and not just focus on one solution.”

“The future is in our region is the fourth aqueduct,” he continued. “It’s not a pipeline. It’s a virtual aqueduct that is a mixture of conservation, storage, recycling wastewater, stormwater capture and infiltration, creating spreading grounds, and other things we need to do across the region. This is the future. But I think recycled water and stormwater management is one of the biggest things we should push hard and continue moving forward.”

Chair Madueño asked how they will ensure that everyone has a reliable water system and that those who don’t have the means are not locked out of the system.

Ms. Romero said they must continue investing in the water infrastructure now so Los Angeles can become locally resilient. “We have to control our own destiny first, so we can better manage the water. We have to invest in recycled water and stormwater. And as a city and a county in the region, we have invested money there. But we still need more.”

Ms. Romero said they must continue investing in the water infrastructure now so Los Angeles can become locally resilient. “We have to control our own destiny first, so we can better manage the water. We have to invest in recycled water and stormwater. And as a city and a county in the region, we have invested money there. But we still need more.”

She also said that the long-term jobs created by the Hyperion 2035 project would be good-paying middle-class jobs, and they’ll be working with trade schools and high schools to ensure residents can access those jobs and those opportunities.

“We need to continue to remind people about the value of the water,” she said. “We have to remind, as we’re asking for additional resources to add value and investments in certain parts of the city, that in the City of Los Angeles, there’s a diversity of people, but also diversity of incomes. So there are some areas we have to target; there are disadvantaged communities and certain pockets of Los Angeles that need additional water infrastructure investments than other parts of our city.”

Councilmember Don Nottoli asked what measures have been implemented for the golf courses in the Coachella Valley.

Mr. Cheng said they have been actively engaged with the golf courses through a consortium called the Golf and Water Task Force. Water agencies recognize the golf courses’ impact on the local economy, so they have been trying to encourage them through rebates. They are hoping for more funding for rebates from the $4 billion that will be available from the Inflation Reduction Act.

“These are difficult conversations we’ve had with the industry; they obviously hold a lot of sway over the local economy,” he said. “So the way that we’re approaching this is to work together and figure out how we can bring down water use on the golf courses but make them still appealing to the residents who live there.”

Councilmember Julie Lee asked how they are addressing the conservation efforts with folks getting sensationalized in the news as water abusers. “Tiered rates are one way to try to control that. But how else can water abusers be held accountable and reduce the inequities that we see between some of these disadvantaged communities and the rich people that may be paying higher water costs but not caring about the conservation of it?”

Mr. Hagekhalil noted that Metropolitan enacted an emergency conservation program that went into effect in June that allocated water to member agencies along with a penalty if they exceeded their allocation. “So within their service area, they had to manage a lot of unhappy people that can afford water; they can pay as much as you want, but there is no water to buy. And water agencies took some drastic actions, especially Las Virgenes.”

He has been looking at the business model for Metropolitan and considering tiered rates at the wholesale level. “As we build resiliency in the system, it should not be on the back of the smaller communities doing the right thing in conservation, especially disadvantaged communities. The cost should be inversely proportional to who is using the water. The biggest problem is that when you conserve and reduce your consumption, water costs are not going down. And people struggle with that.”

He has been looking at the business model for Metropolitan and considering tiered rates at the wholesale level. “As we build resiliency in the system, it should not be on the back of the smaller communities doing the right thing in conservation, especially disadvantaged communities. The cost should be inversely proportional to who is using the water. The biggest problem is that when you conserve and reduce your consumption, water costs are not going down. And people struggle with that.”

“So we’re working through a whole business model review at Metropolitan,” Mr. Hagekhalil continued. “We may have to shift something to incentivize conservation and then build this larger cost of new water that we’re creating on the backs of people who are higher users. So I know prop 26 and prop 218 get in the way of a lot of things, but we need to be creative. We need to find the ways.”

Councilmember Daniel Zingali said, “I know everyone on the panel knows this, but the damage those high-profile water abusers are doing to your goal and our goal of having one conversation and one effort, one California around one water – It’s greater than the damage they’re doing by whatever water they’re wasting. So it makes it very difficult to have the conversation here constructively. So I’m glad to hear you’re thinking creatively, including punitive action. But, as long as that casts a shadow over all the good efforts we see you and your customers are making, it will make it more difficult in an already challenging situation.”