At the September meeting of the California Water Commission, commissioners were given a briefing by the Department of Water Resources on their preparations for yet another dry year and the steps they are taking to prepare the State Water Project for climate extremes and the challenges of drought, flood, and wildfire.

Key takeaways from these presentations:

- The Department of Water Resources is planning for another dry year; given recent years, the Department is learning to expect the unexpected.

- Although conditions at Oroville are greatly improved over last this time last year, the Department is looking to have 1.6 MAF in Oroville before they will consider making some water available for export.

- The Department is working to improve its forecasting by expanding its use of aerial snow surveys which are more accurate, and developing models that are less reliant on historic data and more reliant on modeling based on characteristics.

- The 2023 State Water Project Delivery Capability Report will include climate change data and new risk-informed future projections.

State Water Project drought response

John Yarbrough, Assistant Deputy Director at the California Department of Water Resources, began with an update on climate forecasting.

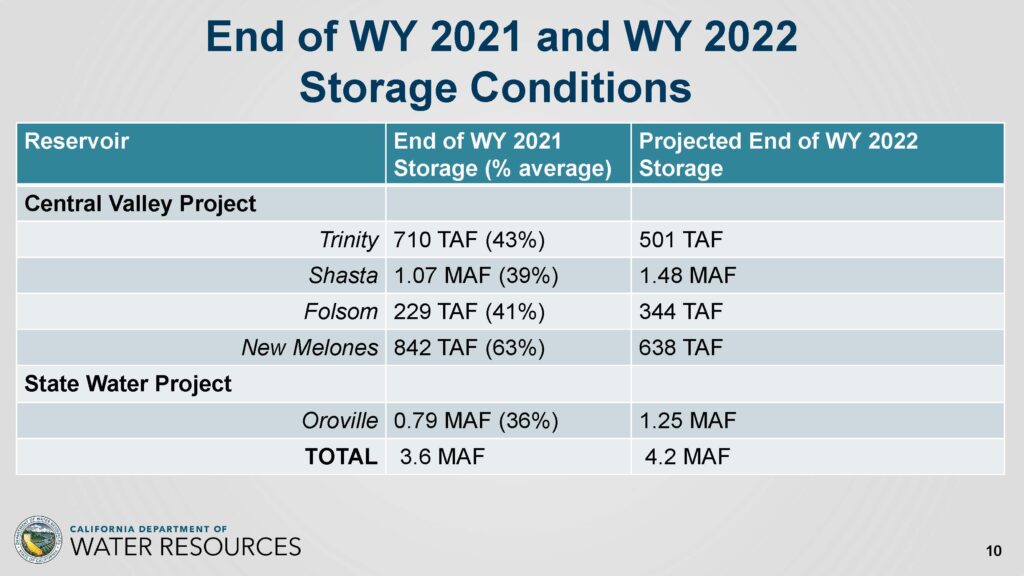

Extreme events and extremely dry periods marked the first months of the 2021-22 water year. By the end of the water year, there was more storage in the reservoirs than the previous year, but still well below average. Conditions are still very much dry, and those extreme conditions last year continue to inform the planning for this next year.

“As we’re thinking about what we might be seeing next year, we have to prepare and expect that we’re going to see things that we haven’t seen before,” said Mr. Yarbrough.

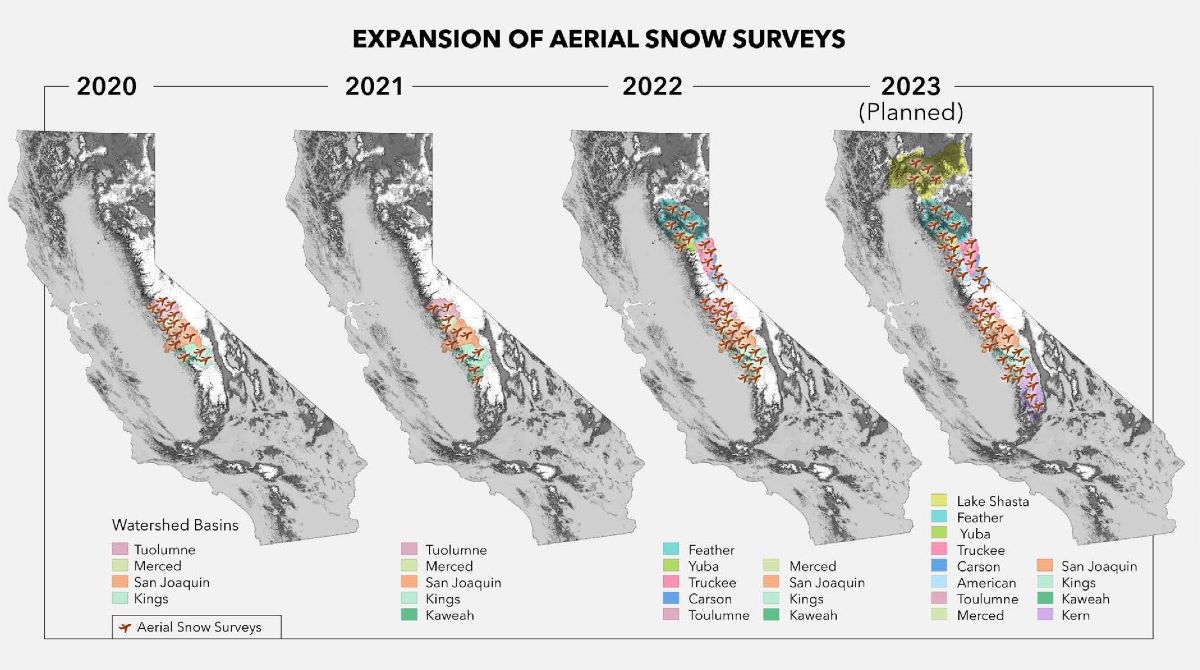

The figure on the left below shows the mean temperature for the Water Year 2021-22; the redder colors represent warmer temperatures. Last year was warmer than average, although not as warm as 2021. The figure on the right shows precipitation for the same period; it wasn’t as dry as the previous year but drier than average.

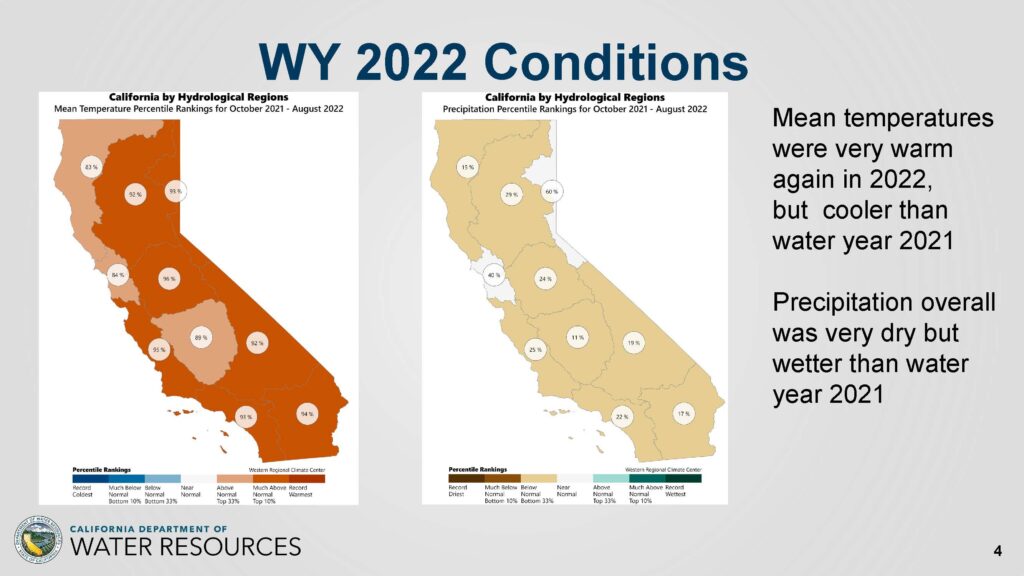

The graphic on the slide is a hydrograph of the Northern Sierra 8-station index and shows how the runoff showed up at the reservoirs. What is unique is the stair-step pattern, which illustrates the extreme precipitation events that were followed by extremely dry periods over what is typically the wettest part of the year. Last year, those two storms provided most of the water supply for the year.

Given these conditions, we need to expect moving forward that it will be different than what we have observed before, said Mr. Yarbrough. “When we look at patterns like this, it really challenges a lot of our practices for how we plan the system for how we’re going to operate for the next year.”

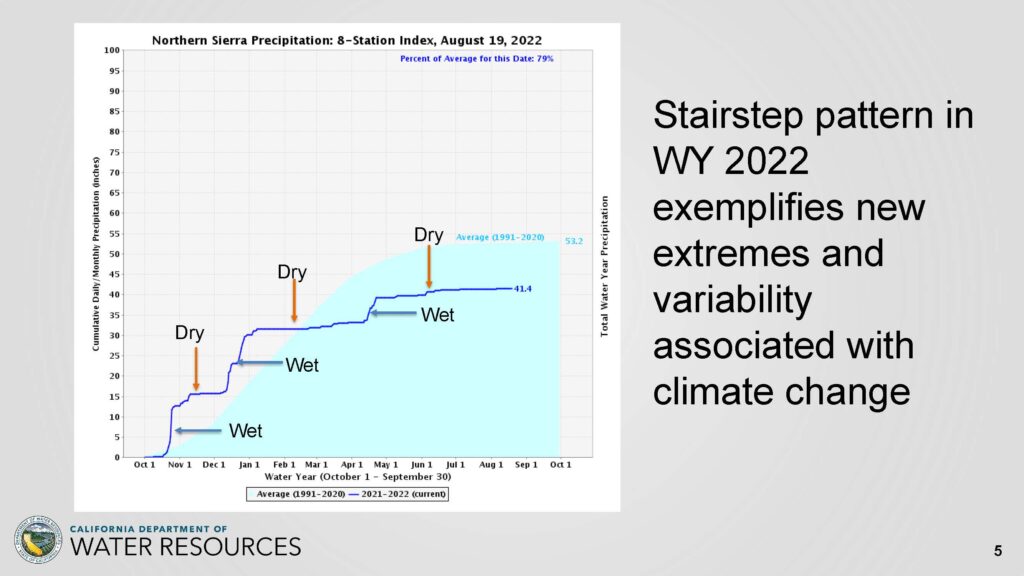

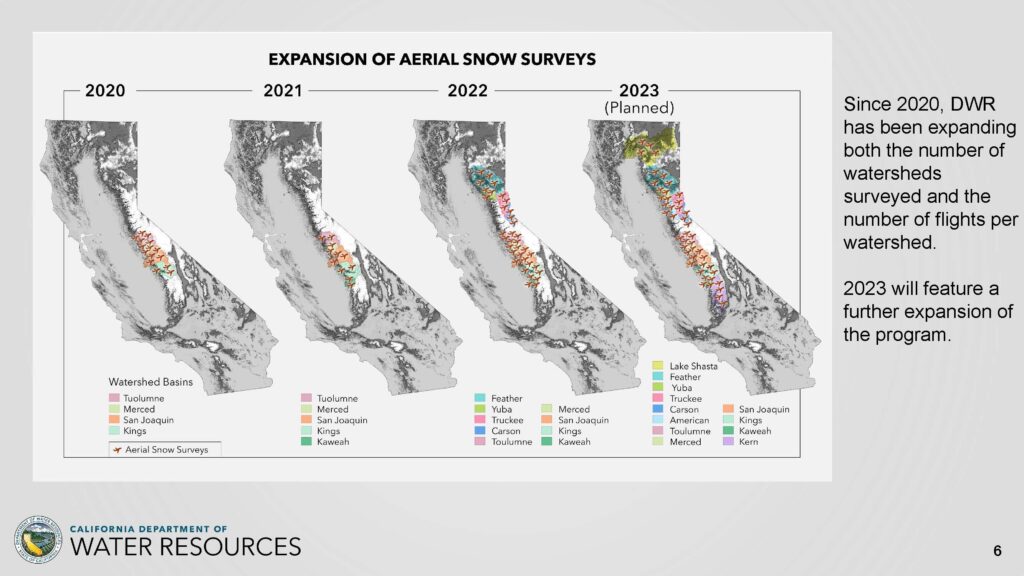

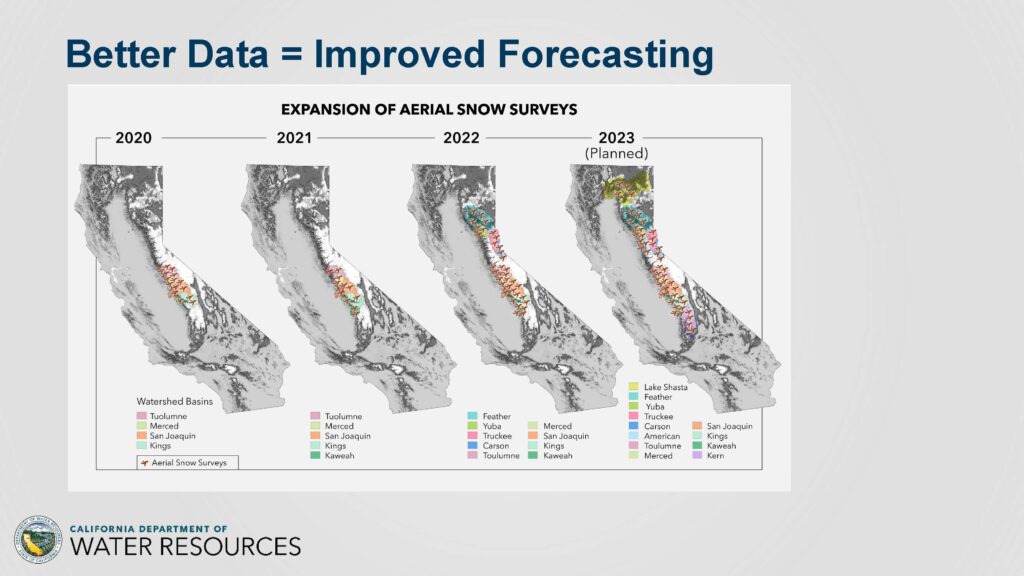

One improvement is that the Department is expanding the use of aerial snow surveys, which take advantage of LIDAR imaging to more accurately measure the snowpack than point measurements. The multiple flights over the year show the distribution of the snowpack and how the snow accumulates, melts, and turns into runoff .

Drought actions

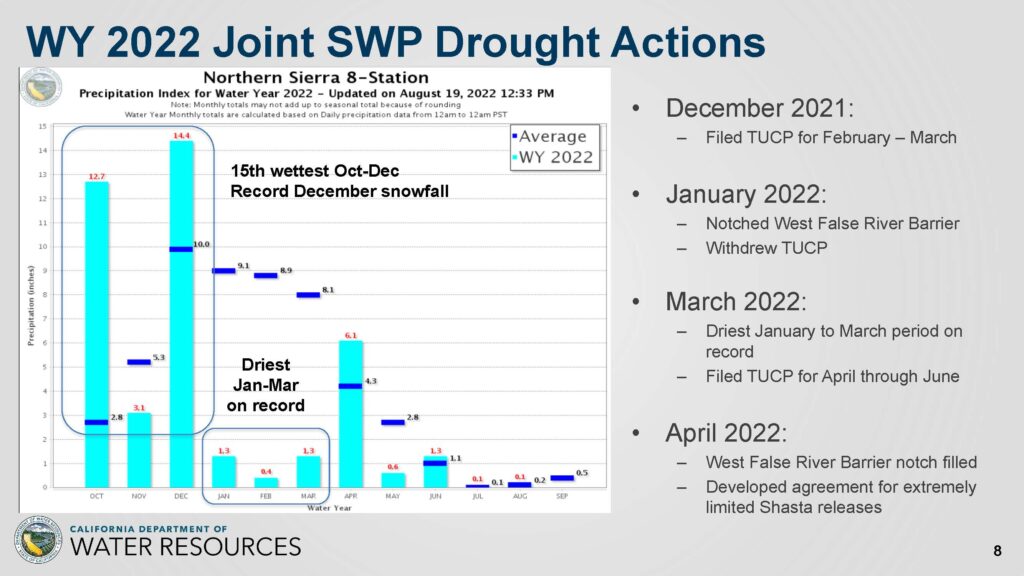

The graphic shows precipitation by month; the turquoise bars show the actual precipitation, and the smaller, dark blue dashes show average precipitation. The graph shows how October and December were much wetter than average, followed by three extremely dry months.

So in December of 2021, the Department filed a temporary urgency change petition (TUCP) with the State Water Resources Control Board. The Department submitted it early in the year to give plenty of time for a full public process. At the time the Department was developing the change petition, only the large October event had occurred, so with the potential for continued dry conditions, Mr. Yarbrough said it made sense to file the TUCP. However, after the precipitation events in December, the conditions improved such that the TUCP wasn’t warranted, so the petition was subsequently withdrawn.

In January, the drought barrier, left in place from the previous year, was notched to allow for fish passage. What followed was the driest January to March period on record, so the Department filed a TUCP for April through June.

Also, at this time, the Bureau of Reclamation and the Department developed an agreement for extremely limited releases from Shasta as precipitation events had helped the Feather River basin and the American basin but missed the Shasta basin, and levels at Shasta Dam were quite low. By April, the Department was filling the notch in the salinity barrier.

The Department worked with the Feather River Settlement Contractors to modify the timing and reduce the water those contractors would receive and issued an allocation for the State Water Project of 5% plus additional for public health and safety.

The chart shows the conditions at the end of the year. Conditions at Oroville are greatly improved over last year. However, Mr. Yarbrough said that the Department is looking to have 1.6 MAF in Oroville before they will consider making some water available for export. He also pointed out the low level in Shasta; better than last year but still quite low.

Planning for 2023

As the Department prepares for yet another dry year, its principles are:

- Support the human right to water

- Protect imperiled fish and wildlife

- Balance and protect beneficial uses of water

- Honor water rights

- Promote fairness and equity in policy decisions

- Prioritize effective and efficient strategies

- Harness science and collaboration

- Continue to explore and implement creative, extraordinary ideas

Objectives:

- Plan for a fourth consecutive dry year and continue preparing for extreme weather events

- Provide for minimum health and safety needs: Low allocations are likely as we start the water year. Depending on conditions, the allocations could again focus on human health and safety needs.

- Maintain suitable water quality in the Delta, which is the source of municipal drinking water for many communities

- Protect species by meeting environmental needs

- Conserve storage to meet future critical needs

- Provide water supply from SWP

- Continued agency and stakeholder communication

Potential actions for 2023

The Department will continue with rigorous multi-agency coordination

If dry conditions persist through 2023, potential actions include issuing another low SWP allocation based on critical human health and safety needs, applying for a temporary urgency change petition and utilizing drought barrier(s), considering the use of SWP terminal reservoir storage, and executing transfers and exchanges south of Delta, if possible.

Other actions outside SWP include coordinating actions with the Central Valley Project, State Water Board curtailment orders, improving voluntary and/or mandatory conservation, and issuing emergency orders and proclamations by the Governor.

The Department will also continue forecast and modeling improvement efforts, such as increasing the aerial snow surveys and developing additional models that are less reliant on historic data and more reliant on modeling based on characteristics, as well as implementing new modeling approaches.

“For the rest of this year, we’re working with our settlement contractors up in the Feather about how to best use the water for rice decomposition that focuses on Pacific Flyway, with the Shasta having so low deliveries there,” said Mr. Yarbrough. “The use of rice decomposition water does become important for the Flyway, so we’re looking at how to really make sure that water is being used in the best way possible while also looking to an eye on having water conserved for next year.”

Climate change and wildfire response planning

Andrew Schwarz, State Water Project Climate Action Coordinator, then discussed the Department’s efforts to improve forecasting, response to fires in the Feather River watershed, and continuing efforts to improve planning for future conditions.

Expansion of aerial snow surveys

The Department has expanded its aerial snow surveys. “Better data really means better forecasting, and better forecasting means we can respond operationally sooner,” said Mr. Schwarz. “And the local water agencies have better information about what allocations might look like, so they can start their planning and conservation efforts a lot earlier.”

The aerial snow surveys are expanding into the Shasta basin and the American River basin, with more flights and more watersheds being covered.

“In 2022, specifically, when the forecasts were not as accurate as in the past, one possible reason for why we thought there was more snow up there was because we only had a small network of sensors throughout the watershed, and those were showing that the snow was deep there,” said Mr. Schwarz. “But in actuality, it wasn’t probably as deep up higher in the watersheds as we thought. So this effort with the aerial snow surveys helps us correct that and understand how the snow is spatially distributed throughout the watershed.”

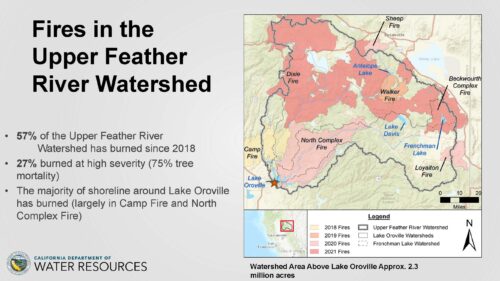

Wildfire response

This year, the wildfire season has been relatively calm, but there were substantial wildfires from 2018 through 2021, with the Feather River watershed being one of the hardest-hit watersheds in the state. For those three years, over half of the watershed burned, with 25% of the watershed burning at high intensity, with tree mortality at 75% or higher.

This year, the wildfire season has been relatively calm, but there were substantial wildfires from 2018 through 2021, with the Feather River watershed being one of the hardest-hit watersheds in the state. For those three years, over half of the watershed burned, with 25% of the watershed burning at high intensity, with tree mortality at 75% or higher.

“That’s an incredible change in the landscape of a watershed,” said Mr. Schwarz. “So we’re trying to get our arms around what this will mean for our operations and the State Water Project in general.”

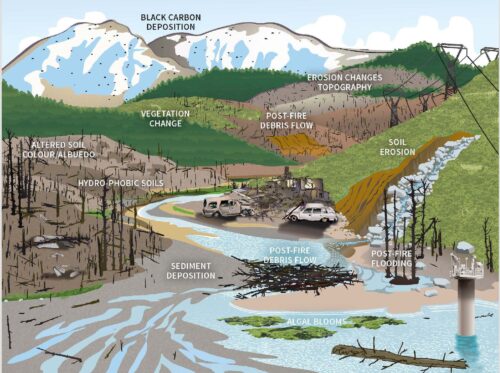

The graphic on the slide illustrates the many impacts of a wildfire on a watershed. These can include:

The graphic on the slide illustrates the many impacts of a wildfire on a watershed. These can include:

- Black carbon deposition on snow, darkening it so it absorbs more sunlight and melts faster;

- Loss of vegetation can mean less evapotranspiration, but less shade can cause snow to melt faster;

- Debris flows and increased sedimentation in the river;

- High heat from the fire can make the soil ‘hydrophobic’ where water will not penetrate into the soil for months;

- Erosion and flooding impacts; and

- Water quality impacts from runoff from burned homes and businesses containing chemicals and contaminants.

After the fire season last year, the Department did a comprehensive impact assessment and action planning for SWP operations and assets throughout the watershed. It is the first step in building an understanding of the information and the next steps that are needed. One gap that was identified was the hydrologic impacts of the large fires in the watershed, so the Department has funded a study with the Airborne Snow Observatory and NCAR to use LIDAR sensor data for the watershed to inform new hydrologic models they are building for the watershed.

“We’ll recalibrate, test the parameterizations, and the modeling of the hydrology in those burned areas so we’ll get a much better sense of how our hydrology is changing because of those fires,” said Mr. Schwarz. “That’s something we’ll be able to iterate on as we go forward with … vegetation doesn’t stay the same for long. It will keep secessing and different species will come in, and we’ll probably have more fire in the watershed, so we’ll be able to adapt as we get better information as we go along.”

Improvements to the Delivery Capability Report

DWR releases the Delivery Capability Report every two years. The report is widely used by State Water Project contractors and others for Integrated Regional Water Management Plans, Urban Water Management Plans, and Agricultural Water Management Plans.

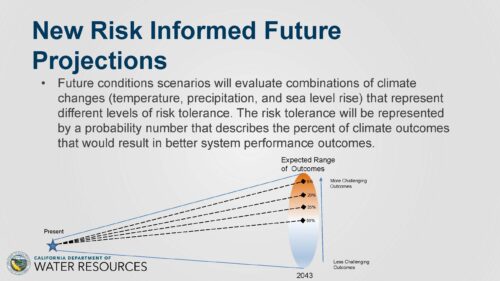

The 2023 Delivery Capability Report will have three improvements: The report will adjust historical data to account for the climate changes that have already occurred; new risk-informed future projections will be developed; and new guidance on using risk-informed projections will be included.

Mr. Schwarz then explained what the new risk-informed future projections are. When thinking about climate uncertainty out into the future, it can be thought of as a ‘cone of uncertainty.’ The star in the graphic shows where we are at present, but as we think about conditions further into the future, that cone of uncertainty gets bigger and bigger.

Mr. Schwarz then explained what the new risk-informed future projections are. When thinking about climate uncertainty out into the future, it can be thought of as a ‘cone of uncertainty.’ The star in the graphic shows where we are at present, but as we think about conditions further into the future, that cone of uncertainty gets bigger and bigger.

“Right in the middle of that cone and the darker areas is probably the most likely place that we’ll end up according to our global climate models and all the information that we have,” he said. “Then the lighter areas are less likely outcomes, but still totally possible. So from the bottom to the top, maybe less challenging to more challenging outcomes. So the projections we’ll be looking at for the 2023 delivery capability report would be out to 2043.”

The report will now provide multiple future scenarios, recognizing the uncertainty we need to plan for and providing some level of conditional probability or expectation of risk that can go along with each scenario.

“We’re hoping to provide more information to improve resilient water management throughout the state by all the folks that use our water,” said Mr. Schwarz. “We’re being transparent about what we don’t know about the future and what we don’t know about how effective the performance of the water project will be in the future, and fully acknowledge that the future is uncertain. And there is a range of possibilities we can say, ‘this is the future; this is what you should plan for.’ It depends on how robust their system is outside of SWP water supplies. Each agency may have different risk tolerance and dependence on SWP supplies, and we want to acknowledge that and allow them to plan for that.”

State Water Project adaptation

The Department has several reports that project the performance of the State Water Project might be 20% worse on average than it is now. Acknowledging that the future climate will be tough, the Department is considering several adaptation measures.

These include:

- The Delta Conveyance Project

- Addressing aqueduct subsidence in the Central Valley so that water can be moved through the system when available.

- Operation and management measures, such as Forecast-Improved Reservoir Operations, improved seasonal forecasting, and working with Army Corps to update the water control manual to manage flood conservation space more effectively and balance that with water supply needs.

- Feather River watershed wildfire mitigation to mitigate for the fires and minimize the hydrologic impacts.

- Enhanced asset management for the State Water Project: asset management and maintenance of DWR’s facilities has been an ongoing concern of the SWP for several years now, but it’s becoming increasingly understood as being a key adaptation strategy as well.

“Our facilities need to be in tip-top condition, be available for operation when water comes,” said Mr. Schwarz. “And in weird times when it’s unexpected. It’s in Big Gulps, and then long periods of nothing. So we need to have those facilities in place and operating when the water arrives.”