In the spring of 2022, the Delta Science Program hosted a series of lunchtime webinars focused on governance in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. The second webinar, held in April, focused on collaborative governance.

The panelists:

- Dr. Andrea Gerlak is a research professor at the Udall Center for Studies in Public Policy at the University of Arizona and a professor in the School of Geography and Development. Her research agenda focuses on cooperation and conflict in water governance, including questions of equity and access, institutional change, learning, and adaptation. She’s an author or co-author of over 100 publications and has two decades of experience leading interdisciplinary Environmental Studies programs and University Community Environmental partnerships.

- Jessica Law is the Executive Director of the Sacramento Water Forum, which brings together diverse interests in the region to focus on balancing two coequal objectives: providing a reliable and safe water supply for economic health and planned development to the year 2030 and preserving the fishery wildlife recreation on aesthetic values of the Lower American River. With more than 15 years of water and environmental resource management experience, Jessica is passionate about building long-term solutions to California’s complex natural resource challenges. Previously, Jessica served as Chief Deputy Executive Officer of the Delta Stewardship Council.

- Matthew Moore is the United Auburn Indian Community’s Tribal Historic Preservation Officer. He’s a retired firefighter and paramedic passionate about native plants, traditional burning, and bringing traditional ecological knowledge into the larger community.

- Dr. Brett Milligan is a Professor of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Design at UC Davis. His research focuses on the critical investigation and design of new infrastructure forms based on landscape processes that foster ecological recovery and social equity. He is a founding member of the Dredge Research Collaborative, which implements transdisciplinary approaches to water infrastructure and the design of dredged landscapes and sediment management. His UC Davis research lab – Metamorphic Landscapes – prototypes landscape adaptations to accelerated climatic and environmental change, focusing on applied fieldwork in floodplains, estuaries, urbanized deltas, and the dynamic interface between land and water. Dr. Milligan’s research approach is transdisciplinary, exploring ways to create new, integrative knowledge across disciplines and the public through design research, ethnography, and extensive fieldwork methods.

Dr. Andrea Gerlak: What is collaborative governance?

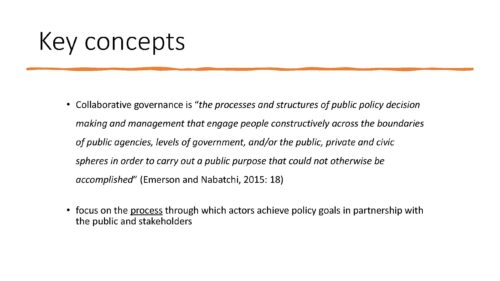

The definition of collaborative governance is shown on the slide. This widely-recognized definition by Emerson and Nabatchi casts collaborative governance as the processes and the structures of how public policy decisions are made and managed. The definition also includes engaging people across the boundaries of public agencies and levels of government in public-private spheres.

The definition of collaborative governance is shown on the slide. This widely-recognized definition by Emerson and Nabatchi casts collaborative governance as the processes and the structures of how public policy decisions are made and managed. The definition also includes engaging people across the boundaries of public agencies and levels of government in public-private spheres.

“The whole idea is about carrying out a public purpose that couldn’t otherwise be accomplished,” said Dr. Gerlak. “So the function of collaborative governance is really to address collective action problems that cross multiple jurisdictions and functional boundaries.”

Collaboration differs from cooperation and coordination; it suggests a much closer relationship. It often entails new structures, shared resources, defined relationships, and communication.

“What distinguishes collaborative governance from governance more broadly, or even environmental governance, is that collaborative governance is really focused on this process,” she said. “It’s very much about partnerships. It crosses government, private sector, and the non-governmental or the civil society sphere.”

Why the rise in collaborative governance? Collaboration is about three decades old for environmental protection and restoration work; it began in the late 1980s into the early 1990s. It can be explained by the multiplication of administrative partners, more government actors playing a role, and the proliferation of political influence outside government circles, with the private sector and civil society demanding more of a role. It formed around the idea that we weren’t doing very well with representative democracy, and there was a stalemate around environmental policy dating back to the 1980s. Collaborative governance is also a response to a deeper understanding of ecosystems and interdependencies and the recognition that we can’t manage them separately.

Why the rise in collaborative governance? Collaboration is about three decades old for environmental protection and restoration work; it began in the late 1980s into the early 1990s. It can be explained by the multiplication of administrative partners, more government actors playing a role, and the proliferation of political influence outside government circles, with the private sector and civil society demanding more of a role. It formed around the idea that we weren’t doing very well with representative democracy, and there was a stalemate around environmental policy dating back to the 1980s. Collaborative governance is also a response to a deeper understanding of ecosystems and interdependencies and the recognition that we can’t manage them separately.

“When I teach collaborative governance to my students, I often talk about the Reagan era,” said Dr. Gerlak. “Collaborative governance is almost a response to the politics of the Reagan administration in the 1980s. And the retreat of government really helps explain the shift in governance towards a more collaborative governance structure or set of processes as federal investment and federal participation declined, and maybe even rules. There was a vacuum around a lot of public policy areas, and the private sector and the public sector in terms of civil society or non-governmental actors really filled that vacuum.”

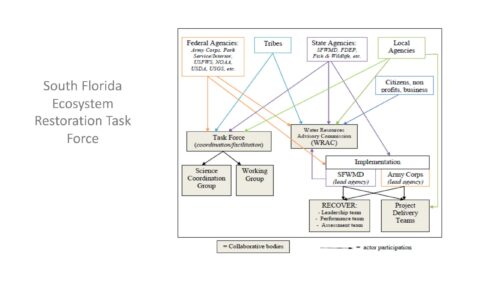

The Missouri River Recovery Program and the Everglades Restoration Program are two examples. In the 1990s, under the Clinton administration and Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt, there was a push for ecosystem restoration and management, a response to violations and conflicts with the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act, and the perceived obstacles to collaboration. In the Delta, Secretary Babbitt played a role in creating new institutional structures and bringing collaborative governance to the Bay-Delta.

The slide shows the organization of the Everglades restoration task force and how all the different actors come together: federal agencies, state agencies, local agencies, tribes, and nonprofits. The task force has been working since the 1990s in new forums and venues for everything from implementation to delivery to science teams.

The slide shows the organization of the Everglades restoration task force and how all the different actors come together: federal agencies, state agencies, local agencies, tribes, and nonprofits. The task force has been working since the 1990s in new forums and venues for everything from implementation to delivery to science teams.

The study and practice of collaborative governance has grown to the point that at the University of Arizona, there is a certificate program for graduate students. Moreover, collaborative governance doesn’t apply just to environmental governance but to healthcare, prisons, and other policy areas.

Researchers are working to understand why collaborative governance structures or processes started, how they’re structured, and the mechanisms for engaging. Some researchers have been focusing on the power dynamics and the power inequities and how those are managed. There has been some research on outcomes as well.

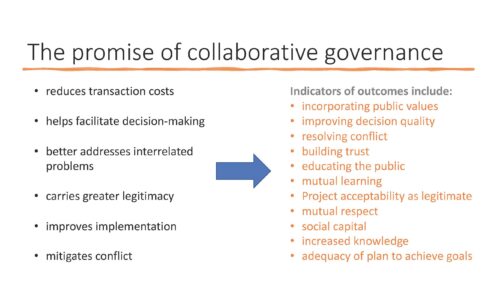

The promise of collaborative governance, listed on the left-hand side of the slide, is that it can reduce transaction costs, facilitate better decision-making, and address interrelated environmental problems. Collaborative governance could give greater legitimacy and improve implementation, hopefully reducing or mitigating conflict.

The promise of collaborative governance, listed on the left-hand side of the slide, is that it can reduce transaction costs, facilitate better decision-making, and address interrelated environmental problems. Collaborative governance could give greater legitimacy and improve implementation, hopefully reducing or mitigating conflict.

On the right-hand side of the slide are the indicators of outcomes, or what researchers are looking for to see how collaborative governance structures or processes meet these goals. They look at how public values are incorporated, if the conflict has been reduced, or if trust has been built. This is evaluated by surveys, interviews, and focus groups to understand people’s perceptions, to look at decision-making in collaborative governance processes, and to understand better if these outcomes have been met.

What does the research say about the performance of collaborative governance? Dr. Gerlak said the research can be distilled into three points:

- It’s important to get the people right. This means bringing the people with the right expertise together with the resources and knowledge and the people who are affected by the decisions that will be made by the collaborative structure. Excluding key people or particular forms of knowledge can compromise the collaborative governance processes.

- The commitment of the government agencies is necessary for funding, leadership, and expertise. The research found that if agency culture works against this, or agency practices dilute or diminish the government’s role, that can compromise collaborative governance.

- The process matters. The research shows that collaborative governance has a positive effect on the perceived policy or program effectiveness, and there is good evidence of stakeholder cooperation and consensus through collaborative governance. There is also the promise that collaborative governance will lead to improved environmental outcomes, but the evidence is more in its infancy, as there are a lot of challenges and time lags involved with this research. Still, there is some evidence from a set of cases that collaborative governance processes lead to greater environmental and improved environmental outcomes.

The research has found that an effective governance process has:

- face-to-face dialogue;

- an open and inclusive process with broad participation and diverse ways of knowing are incorporated;

- clear ground rules about how the process works and process transparency such as access to meeting minutes, clear agendas, and the like;

- deadlines help provide accountability;

- field trips build community and knowledge; and

- mechanisms to support learning where actors can reflect on decisions made, reports that were written, and meetings that were held to be more adaptive to change, to learn from them, and make better decisions going forward.

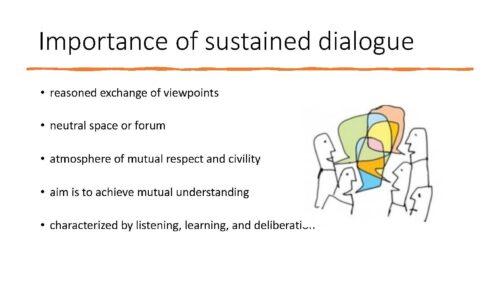

Sustained dialogue is important; Dr. Gerlak said there wasn’t a paper she found that didn’t talk about it. “This is the notion that you’re bringing folks together and having a conversation that’s iterative and sustained; it’s not a one-off. The reason for the dialogue is to exchange viewpoints in an atmosphere that supports mutual respect and civility. It’s about trying to achieve mutual understanding, even if you don’t get a consensus. It’s about trying to hear and listen to others and doing so in a neutral space or a forum. This is characterized by the notion of listening, learning, and being deliberative.”

Sustained dialogue is important; Dr. Gerlak said there wasn’t a paper she found that didn’t talk about it. “This is the notion that you’re bringing folks together and having a conversation that’s iterative and sustained; it’s not a one-off. The reason for the dialogue is to exchange viewpoints in an atmosphere that supports mutual respect and civility. It’s about trying to achieve mutual understanding, even if you don’t get a consensus. It’s about trying to hear and listen to others and doing so in a neutral space or a forum. This is characterized by the notion of listening, learning, and being deliberative.”

Emerson and Nabatchi authored a book that was a synthesis of the research on collaborative governance, which focused on collaboration dynamics, the principles of engagement, joint capacity, and shared motivation; it’s how these dynamics work together. The authors describe them as gears that all work together.

“Collaborative governance scholars aren’t thinking about the process of collaborative governance as a checklist,” said Dr. Gerlak. “It’s very much about how these different factors come together to reinforce one another and to create a dynamic that is positive and intentional and adaptive. So it isn’t just putting processes or structures in place one by one but thinking about the larger dynamic.”

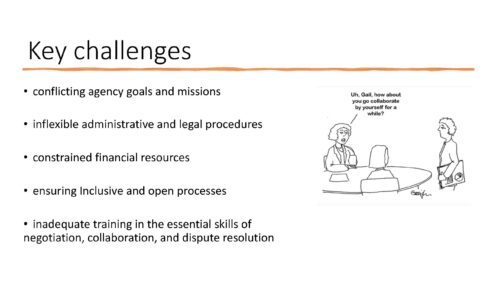

Of course, there are challenges, she said. “Every paper is littered with challenges and things that didn’t quite work. It’s everything from conflicting agency goals to administrative or legal procedures that work against a collaborative process, not having enough money, or the resources or the science you need, and making sure you keep a process open and inclusive over time. It’s really training folks about how to listen, how to talk, how to resolve disputes, and how to negotiate.”

Of course, there are challenges, she said. “Every paper is littered with challenges and things that didn’t quite work. It’s everything from conflicting agency goals to administrative or legal procedures that work against a collaborative process, not having enough money, or the resources or the science you need, and making sure you keep a process open and inclusive over time. It’s really training folks about how to listen, how to talk, how to resolve disputes, and how to negotiate.”

Practitioners face challenges as well. Research about the skills practitioners need include coordination, negotiation, persuasion, managing complex networks of actors, and relying on these interpersonal skills. It also includes inter-organizational processes, working both within and outside your network, how to use technology, how to think about performance management effectively, how to have really good transparency and decision making, and how to keep being creative in how you craft different channels for citizens to participate.

Jessica Law: The Sacramento Water Forum & Collaborative Governance

The Water Forum, signed in 2000, has two coequal objectives: to provide a reliable and safe water supply for the Sacramento region’s economic health and planned development to 2030 and to preserve the fishery, wildlife, recreation, and aesthetic values of the Lower American River.

“This is not just our goal or mission; this is our mantra every day,” said Ms. Law. “It’s very much a part of our conversation at the Water Forum when we come together.”

Ms. Law has been thing about the ‘secret sauce’ or the magic of collaborative governance. Face-to-face interaction is important. Although that has been more difficult with COVID, they held an open house for a project at Ancil Hoffman Park. It was a great opportunity to meet face-to-face to build relationships. In addition, a field trip was held for Water Forum members, resulting in modifications to the project.

Ms. Law has been thing about the ‘secret sauce’ or the magic of collaborative governance. Face-to-face interaction is important. Although that has been more difficult with COVID, they held an open house for a project at Ancil Hoffman Park. It was a great opportunity to meet face-to-face to build relationships. In addition, a field trip was held for Water Forum members, resulting in modifications to the project.

“There’s so much history and collaboration here that really makes our project successful,” she said.

The Water Forum has had a restoration program for about ten years, primarily funded through the Central Valley Project Improvement Act or CVPIA; there is also some state funding through Prop 68.

The main focus is salmonid restoration; they place a lot of gravel to produce spawning and rearing habitat. The project at Effie Yeaw was one of the larger projects; it presented an opportunity to engage with the community and build partnerships with the Effie Yeaw Nature Center and Sacramento County Regional Parks. Two more projects will be constructed this year, with several more in the works. They are pursuing a programmatic permit for ten sites along the American River. Most projects will be funded through the CVPIA, state funding, and potentially the voluntary agreement process under negotiation.

“So there’s a lot of regulatory framework for the work that we do, but this is really what it looks like when this regulatory framework comes together,” said Ms. Law.

Collaborative governance can include state agencies, federal agencies, local agencies, private interests, and nonprofits. “I’m seeing this as we go through our work on habitat restoration, just how critical those partnerships are, whether it’s public, private, state or federal, or sort of all of these entities together.”

Another large part of the Water Forum’s work focuses on flows and operations out of Folsom Reservoir and the Lower American River. Water levels in the river change throughout the year. Last summer, the water temperatures were extremely high, impacting salmon spawning and juvenile salmon’s health in the river.

Another large part of the Water Forum’s work focuses on flows and operations out of Folsom Reservoir and the Lower American River. Water levels in the river change throughout the year. Last summer, the water temperatures were extremely high, impacting salmon spawning and juvenile salmon’s health in the river.

“The Water Forum has worked over the past 15 years to pull together a flow management standard that balances both the water supply and the health of the fisheries in the Lower American River,” said Ms. Law. “It’s a very technical document. We call it the modified flow management standard. It’s modified because it’s gone through several iterations. And currently, it’s incorporated in the 2019 Biological Opinion for Reclamation, which means the work of the Water Forum developed through the collaborative process is incorporated into the federal document regulating flows.”

Reclamation has been operating to the modified flow management standard for the last two years. The Water Forum remains active, engaged, and at the table with the federal and state agencies, working through the operations on a daily or weekly basis. There’s a lot of science, modeling work, and a strong focus on temperature, as releases from Folsom Reservoir can control the temperature.

“This year, again, we’re in a drought, so some really difficult decisions need to be made,” said Ms. Law. “But I’d say the Water Forum has been doing a good job being at the table and trying to help as much as possible support these decisions.”

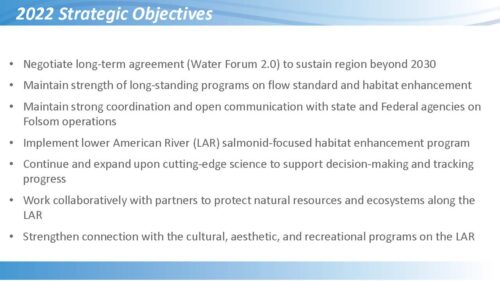

The slide lists the Water Forum’s strategic objectives for 2022.

The slide lists the Water Forum’s strategic objectives for 2022.

“A lot of our work is about maintaining strong coordination, collaboration, and connections,” she said. “It is just such an integral part of the work that we do. There’s no Water Forum working alone. The Water Forum only exists because of the relationships between local, state and federal agencies, all of the caucuses in the Water Forum.”

The Water Forum agreement was signed in 2000 after seven years of intense negotiations in the region concerning the conflicts with Auburn Dam and additional diversions from the American River. The process used an interest-based negotiation structure comprised of individual caucuses that then set the negotiation table to come together and work through the agreements. While the current agreement extends to 2030, they are starting now to allow ample time for renegotiations.

The slide lists the main principles of interest-based negotiation from the book, Getting to Yes.

The slide lists the main principles of interest-based negotiation from the book, Getting to Yes.

“These points are the principles of our work, not just bullet points on a slide,” said Ms. Law. “We talk about this every single day. Separating the people from the problem, focusing on interests rather than position, generating various options before settling on agreements, and insisting that the agreement be based on objective criteria – these principles are present in our conversations in all of our work with the caucuses. This is really our secret sauce. It is the way that we continue to come together collaboratively and productively. These principles are really important to our work.”

When Ms. Law joined the Water Forum in January 2021, some foundational work for the renegotiations had been done, but the effort hadn’t begun to lay out the different pieces for the Water Forum agreement process. “The process is very important; we need to be very clear on our process and how we get from point A to point B to point C,” she said.

Last year, they worked on the major building blocks, focusing on desired outcomes and key management questions. What are we doing? Why? What are the major outcomes that we’re looking for? They have also discussed a new public caucus, current interests and issues, and technical analysis.

“It’s really making sure that we have the right people at the table, that people at the table understand where we’re going, what our desired outcomes are, and what our core questions are,” said Ms. Law. “Then as the caucuses come to the table, they’re gathering together and really understanding what their interests are as a caucus – not positions, but interests – then how those interests align within the caucus and amongst the different caucuses.”

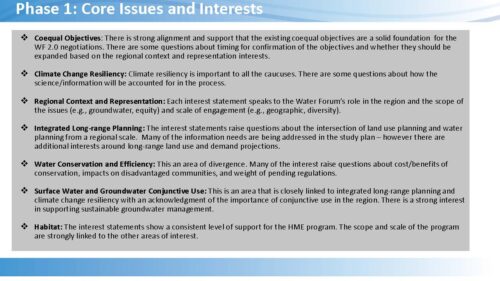

The main issues and interests for the Water Forum 2.0 process are listed on the slide; this is the scope of where the Water Forum is trying to go. Climate resiliency is a major interest, so the process needs to consider climate resiliency, regional context, and representation in the context of the coequal objectives. Who are we? What’s our role? What’s our legacy? What’s our scale of engagement? Does that need to be broadened? What does that look like? And how do we do that well? Those are then linked back to quantitative objectives for each of the areas.

The main issues and interests for the Water Forum 2.0 process are listed on the slide; this is the scope of where the Water Forum is trying to go. Climate resiliency is a major interest, so the process needs to consider climate resiliency, regional context, and representation in the context of the coequal objectives. Who are we? What’s our role? What’s our legacy? What’s our scale of engagement? Does that need to be broadened? What does that look like? And how do we do that well? Those are then linked back to quantitative objectives for each of the areas.

Learning and engagement remain important as the Water Forum works on phase 2. They understand the emerging areas of agreement, but where is the divergence and what are the solutions?

“The Water Forum is really trying to pivot as an organization, maintaining the foundation on interest-based negotiation, and using it to adapt and think about climate change resiliency,” concluded Ms. Law.

Matthew Moore: Tribal Historic Preservation & Collaborative Governance

The United Auburn Indian Community is a sovereign government comprised of the Nisenan Maidu and Miwok Tribes. They are located just outside of Auburn in Placer County.

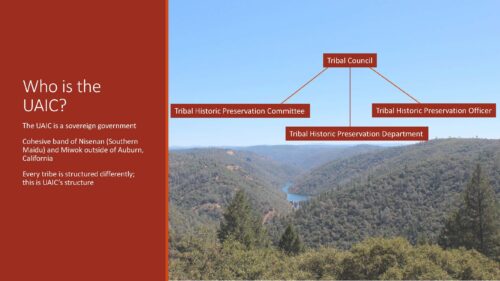

The slide shows their Tribal structure:

The slide shows their Tribal structure:

- At the top is the Tribal Council, with five members.

- The Tribal Historic Preservation Committee has a chairman and four members

- The Tribal Historic Preservation Officer

- The Tribal Historic Preservation Department is divided into two categories:

- Tribal Heritage: These are people specialized in traditional ecological knowledge, history, customs, knowledge, and skills as to how they interacted with the landscape and managed the lands before contact.

- Regulatory process: These folks receive consultation letters, review them, and distribute them to the appropriate individuals to follow up.

Mr. Moore noted that each Tribe determines its structure, so it’s important to understand that some Tribes might operate differently than others.

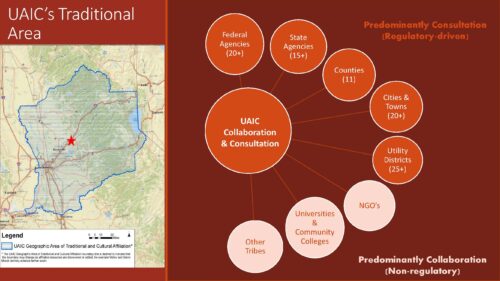

United Auburn Indian Community’s traditional area consists of several counties from Plumas County south to El Dorado County, from the Sierra Nevada to the valley floor. They consult and collaborate with over 20 federal agencies, 15 state agencies, 11 counties, 20+ cities and towns, and numerous utility districts. They also collaborate with NGOs, universities, community colleges, and other tribes.

United Auburn Indian Community’s traditional area consists of several counties from Plumas County south to El Dorado County, from the Sierra Nevada to the valley floor. They consult and collaborate with over 20 federal agencies, 15 state agencies, 11 counties, 20+ cities and towns, and numerous utility districts. They also collaborate with NGOs, universities, community colleges, and other tribes.

United Auburn approaches collaboration with the belief that environmental is cultural and cultural is spiritual. “When we consult or collaborate, it’s usually over natural resources, whether it’s the feds or the state, or locals, and we always say that all resources are cultural,” said Mr. Moore. “So when we talk about specific resources, we don’t see a difference between modern resources and cultural because they’re all the same … If you don’t take care of one, you’re not going to have the other in the future for healthier people, and survival in general.”

Kinships and guardianships are about the relationship between the people, their communities, and the land itself, typically referred to as stewardship. “Stewardship is something that we used to be able to do, but we don’t have the ability to steward anymore because we don’t have the lands,” said Mr. Moore. “Our native landscapes … we were prohibited from doing certain activities at one point. Laws were changed, and many things we did were outlawed so that the stewardship went away.”

Kinships and guardianships are about the relationship between the people, their communities, and the land itself, typically referred to as stewardship. “Stewardship is something that we used to be able to do, but we don’t have the ability to steward anymore because we don’t have the lands,” said Mr. Moore. “Our native landscapes … we were prohibited from doing certain activities at one point. Laws were changed, and many things we did were outlawed so that the stewardship went away.”

A new management style of the land came about with colonization, and once Native Americans were no longer stewarding their lands, the cultural resources and the health of the ecosystem degraded. “It was our relationship with the land and the other communities, how we went about our seasonal activities, and putting our work and hard labor back into the land so that through the seasons, we were ensuring that we have healthy crops in spring and summer. Many of the activities would be in the fall, and many were family and community events. So it was kind of that tide in nature that they always believed in.”

“We are still here, and we still have that connection,” continued Mr. Moore. “We want to have that ability to access the lands once again so that we can put some attention back into the landscape … We have the knowledge; we have that connectivity to the past. We’ve seen the changes occur over the decades. Our traditional ecological knowledge proves – and even science nowadays shows that our indigenous technologies were very strong and in-depth. And those are the things that we need to start doing once again.”

So educating the public agencies and their partners is important. Even though consultation is regulatory-driven, early consultation can lead to collaboration with groups with the same interests.

“We need to start dropping the hard boundaries: the ‘us’ and ‘them,’” said Mr. Moore. “How do we get through this? The forest tribes can’t do this alone. So it will take partnerships and collaboration moving forward for all of us. We’re all here together, so we need to figure this out together.”

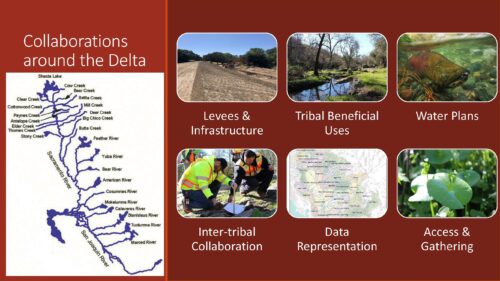

With respect to the Delta, the Tribe has done a lot of work throughout the region, mostly around levees. The levees along the waterways protect the communities, but historically, there were Native American villages located along the waterways, from the main rivers and tributaries up into the ravines and the hills.

With respect to the Delta, the Tribe has done a lot of work throughout the region, mostly around levees. The levees along the waterways protect the communities, but historically, there were Native American villages located along the waterways, from the main rivers and tributaries up into the ravines and the hills.

“The watersheds are usually the places where we lived,” said Mr. Moore. “Anytime you enter those areas, you’ll find evidence of indigenous habitation – even modern habitation because we’re still here.”

Native American villages were either covered up or destroyed by constructing levees up and down the waterways. “A lot of work and effort went into that, and not always the best consultation, but over time, we just demand that we had to be at the table, and through that, we were able to figure things out as far as avoidance or how to reduce the effects of some of these projects,” said Mr. Moore.

Tribes don’t have access to the lands they used to and don’t hold large amounts of lands they can benefit from. Most times, they were given a piece of land to live on, and that was it; the rest was off limits.

“So it’s really about us getting back out and having access to the land, “ he said. “That’s going to happen through collaboration and consultation. I think more agencies are willing to listen and see the benefits of letting tribal people come out and be on their land because we’re the ones that know how to steward and tend to the health of our landscapes. We know how to maintain the indigenous plant species through cultural fire that eradicates all the invasives and reduces the competition between plant communities, which ultimately has a lot of effect on our water, and how the water comes off our hills and into our waterways.”

“When it comes to water quality, cultural burning also helped improve not just the soil health, but the indigenous plant communities relied upon that burning process as they’re very fire-adapted,” he continued. “In the long run, that carbon sequestration has so many benefits, all the way down into the waterways that help improve the water by cleaning it. The charcoal absorbs impurities, which helps clean the water. So just one process just has multitudes of benefits for multiple species. And not just humans and plants that they consumed or used for medicine; it was all the other species. Everything’s tied together, so the health of one community leads to the health of others.”

United Auburn works with a lot of other tribes in the area. Mr. Moore said that they are one of the few federally recognized Tribes, so they help support neighboring Tribal communities that don’t always have the staffing or capabilities.

Gathering traditional food sources, medicines, and other materials is problematic as they don’t have access to the lands anymore, and on the lands they do have access to, the environment is so unhealthy that the materials are suffering, he said. Basket makers are struggling because the materials they use rely on fire to produce usable materials.

“When we look around, we might see native plant communities, but they’re not healthy, and materials are practically unusable because they haven’t been tended to,” said Mr. Moore. “So that’s where we’re coming from when it comes to the collaborations and consultations, which leads to hopefully more positive things in the future. And then moving forward with the agencies more efficiently as we gain relationships and build trust; a lot of it is trust building.”

“We always advocate for early consultation, especially in the planning stages, or even a feasibility study,” he continued. “We have a lot of information and knowledge that people don’t realize. So it’s not just looking it up online and cherry-picking information; there’s a lot more to it. There is background that we can provide to agencies and groups if they’re planning a project, which, for us, leads to avoidance of our sensitive sites, cemeteries, gathering areas, hunting, and fishing areas, so that we can protect and ensure those for future generations.”

The way NEPA and CEQA processes categorize things doesn’t fit with Tribal values; it’s like putting a round peg in a square hole. “But once agencies start to understand our values and how that looks, they start to understand where the sticking point is between the two, and hopefully, we can make changes to get around that and move on together. Because not all projects usually end up with favorable outcomes for tribes.”

Mitigation is a red flag to Mr. Moore; he views it as something lost and mitigation as the band-aid to make it better. “For me, that’s not acceptable as their mitigation usually doesn’t nearly cover the negative effects or poor outcomes we experience.”

Early consultation and collaboration, in the long run, save agencies money as they don’t have to redo plans and waste time and money fixing things, and agencies are usually happier with the outcome.

“With mitigation and impacts to cultural sites, it’s always asking forgiveness instead of permission,” said Mr. Moore. “If you’re there early enough, you don’t need to ask for forgiveness because we can figure these things out together. And just have a better product and the outcome where everybody’s happy. And then some things that we can live with and know that we didn’t destroy, but we protected, and all sides are happy. These form really good relationships over time.”

Brett Milligan: Co-design and Franks Tract Futures

Dr. Milligan’s presentation was on the Franks Tract Futures Project, an example of collaborative governance. The Franks Tract Futures Project utilized co-design, defined as collaborative problem-solving and innovation outcomes that are achieved through an inclusive and equitable design process.

“Co-design is collaborative design,” said Dr. Milligan. “It’s collaborative in the sense that it involves all who might be affected by a plan or a design, and it’s collaborative because it integrates knowledge and expertise from a range of experts as well as local knowledge from the people who live there. So, it is both public and disciplinary based, so it’s transdisciplinary. Design is broadly conceived as intentional or creative ways of bringing about the desired change from a given condition.”

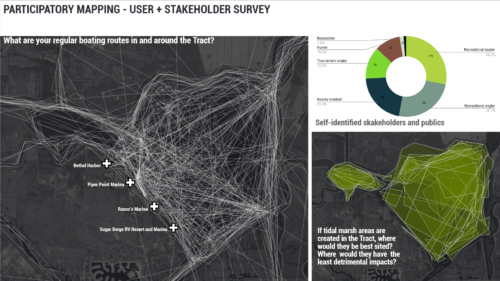

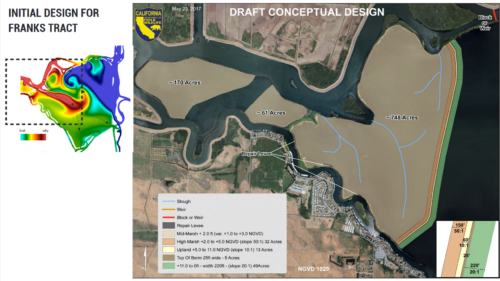

Franks Tract is a flooded tract in the central Delta; the levees broke in the late 30s and were never repaired. It is a State Park, a little over 3000 acres, with Bethel Island along the edge, and has a lot of recreational uses.

Franks Tract is a flooded tract in the central Delta; the levees broke in the late 30s and were never repaired. It is a State Park, a little over 3000 acres, with Bethel Island along the edge, and has a lot of recreational uses.

Franks Tract has developed into a very peculiar tidal lake, and it has become quite a problem for the state. One is the novel ecosystem; there’s not much habitat for native species, particularly the Delta smelt. The other big problem is it’s a source of salinity intrusion into the Delta; having this open water body that allows the salty water from the Bay to come in can make it problematic to export water.

So the state developed a conceptual design that would have filled up the northwest corner of the tract with dredge material to create tidal wetlands, bringing them back up to the elevation where those would be. If they built the project, it would plug the hole where the salinity is coming in and create about 1000 acres of tidal wetland habitat for smelt and other species, which is really needed in the area.

So the state developed a conceptual design that would have filled up the northwest corner of the tract with dredge material to create tidal wetlands, bringing them back up to the elevation where those would be. If they built the project, it would plug the hole where the salinity is coming in and create about 1000 acres of tidal wetland habitat for smelt and other species, which is really needed in the area.

However, while the modeling for the project would have met the technical goals, it was developed without community input and therefore uniformly rejected as it would have impacted boating navigability and recreational opportunities, such as bass tournaments, boating, and hunting.

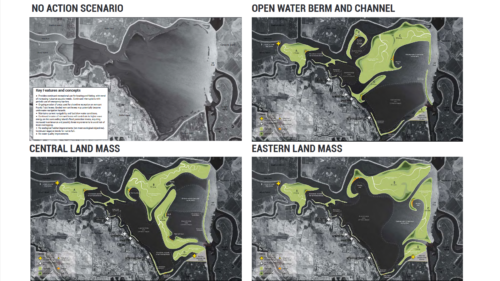

So the Franks Tract Futures Project was the second round that involved the community in the planning process. After a year and a half, the outcome was a solution that not only met the state’s two goals of ecology and water quality but also improved recreation and could potentially contribute to the local economy.

Dr. Milligan agreed that process is very important. The Franks Tract Futures Project process had an interdisciplinary team with much disciplinary and cross-disciplinary knowledge. However, the team was rather small compared to the steering committee, which consisted of all the senior agencies responsible for decision-making, funding, and implementation. In addition, there was an advisory committee that included the stakeholders, such as marinas, local fisherfolk, hunters, duck clubs, and others who might be affected by the change.

“So we brought all of these people together and began by revisiting the objectives of this project,” said Dr. Milligan. “What does everyone want in it? And how do we set those objectives transparently? How do we measure them? And then how do we work forward iteratively to try to meet them through trying different alternative types of design with these folks? This is often called structured decision making, where you are very transparent about how you’re working and what you’re working towards.”

This resulted in a broader suite of goals for the project. Water quality was a key concern of the state. The ecological goals were expanded beyond Delta smelt to include other listed fish, sport fish, and waterfowl. The process included consideration of the local economy, recreation, navigation, and flood protection.

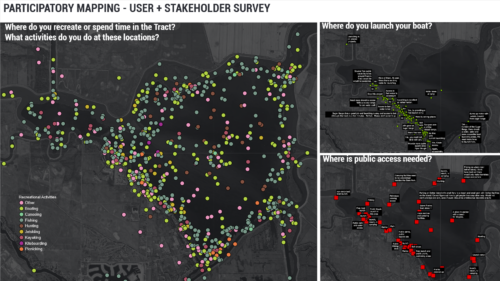

At the kickoff meeting, they asked folks, how do you see this place? What do you value in this track? How do you use it? They launched a survey using maps to ask questions such as where do you hunt, how do you navigate through the tract, and where is the best place to put a marsh?

“Perhaps most importantly, we said, where do you think we might improve things from your point of view?” said Dr. Milligan. “Because when we first came out here, everybody said, ‘don’t touch anything; we love it.’ But the more we were out there, the more people talked about things they didn’t like, such as shallow water, boating hazards, and weeds. And when people were asked, what they might want to improve, it opened up the conversation, where we could start to talk about how this tract is changing, whether we want it to or not, like everything in the Delta. There were a lot of things they didn’t want to happen, and it really fostered a discussion of how we collectively want to try to guide change in the design of this tract.”

Then for the next year and a half, there was a series of workshops and an iterative design process. Six different designs that would meet the project goals while improving things for the local community were refined at each iteration based on stakeholder input.

“What’s important when thinking about collaborative governance is the experience and the role of face-to-face interaction of working in an environment like this, and actually spending time sharing ideas,” said Dr. Milligan. “I felt like within each one of these workshops, there was a lot of co-learning; we were learning from the community that was learning more about the design process, and so forth. Over time, I felt like we developed something together; we ended up with three designs that met the state’s needs and also were agreeable to the advisory committee, in addition to the no-action scenario.”

“What’s important when thinking about collaborative governance is the experience and the role of face-to-face interaction of working in an environment like this, and actually spending time sharing ideas,” said Dr. Milligan. “I felt like within each one of these workshops, there was a lot of co-learning; we were learning from the community that was learning more about the design process, and so forth. Over time, I felt like we developed something together; we ended up with three designs that met the state’s needs and also were agreeable to the advisory committee, in addition to the no-action scenario.”

They put another survey online with the selected designs, made 3D models of the designs, and asked folks to rate them and comment on them.

“We were really surprised because all of the designs rated higher than the no-action alternative, and we started from a place where everybody said, don’t touch anything.”

The final preferred design is shown on the slide. The wetland and upland areas are in the middle, open water in front of the marinas, and additional recreational features and beaches have been incorporated.

The final preferred design is shown on the slide. The wetland and upland areas are in the middle, open water in front of the marinas, and additional recreational features and beaches have been incorporated.

“I personally fought very hard to get it into the document that none of the ideas will go forward unless the recreational and cultural aspects are kept in the design,” said Dr. Milligan. “That is how we all moved forward together and created this collaborative thing. What was amazing about the project was that we ended up with a design far better than what we started with. And that, I think, exemplifies a multi-benefit adaptation project with community support.”

“But the big question I have here is, what’s next? This project ended a couple of years ago, or a year and a half ago. And as far as I know, nothing’s happening. It is out of my hands. So this is a question of when we do achieve collaboration with people outside of direct government, what is the responsibility of government to those people who’ve put time into these things to follow through? Or does that then put the onus back on the government to find new ways of collaborating across agencies to find something that meets multiple agency goals rather than one and requires a lot of creativity and collaboration on their part to make it work?”

QUESTIONS & ANSWERS

QUESTION: How does government pick up where these collaborative processes leave off? What are the connections between these less institutionally formalized or more multi-sectorial processes? How do those then become part of the institution that will create the structure that will allow them to be implemented or put into practice?

Dr. Andrea Gerlak: “There’s not a lot of good research around this. I think it’s up to this larger collaborative process to decide which of these things it wants to take up and how it takes it up. There are resources and time. Some initiatives start and go on for a while and then die; they had a purpose to bring people together to talk in a certain way and then fade away. If you look at the history of collaboration in the Bay-Delta, the model goes back to an EPA initiative that started bringing people together in forums to talk a certain way. That went away because funding and leadership faded.

So I see it as an evolution of learning and change over time. Maybe it isn’t so much about maintaining all of the specific processes. There are these different kinds of streams, or like ebbs and flows, that happen over time. And if we think about them as all processes that allow folks to come together and learn, maybe that’s okay.”

Jessica Law: “I was thinking about where this all comes together. I’ve been thinking about this a lot with the Water Forum. It’s an organization that’s been around for 20 years. We’ve got a bunch of new staff, and we’re reinventing the program in a way. But at the same time, we’re trying to hold true to the work we have been doing, which is the scientific and technical work around a flow management standard and all the habitat enhancement work. I don’t know if we figured this out yet, but I think there’s a graceful way to take all of the regulatory requirements and programs and influences – when you pull all these together, the intent of these programs and the intent of the legislation, this is what it looks like, and this is how it’s actually implemented.

Somebody asked a question about the Voluntary Agreements. There was a big announcement a few weeks ago about the Voluntary Agreements. The Water Forum is envisioned as the implementing organization for the American River region, and it’s very much how the Water Forum is structured now. We will need to change some things, and our financial structure will change if this is all implemented. I think overall, you want to have partners that are local organizations where they can adapt to the new regulations and new information that’s coming out and integrate it all. So that’s how I’m starting to think about it.”

QUESTION: Regarding Tribal consultation, what are your reflections about best practices and ways to enhance the value of collaboration between Tribal and non-Tribal groups?

Matt Moore: “For us historically, we’ve come into some of these discussions midstream. We often don’t get the initial consultation, but somehow, through the process, we get involved. It has been difficult for us because you’re playing catch-up at that point. So instead of getting ahead of the issues, it goes back to that ‘collaboration instead of consultation’ mindset, where it’s purely regulatory. We come into situations where policies or regulations are so set that they’re unwilling to adapt or adjust to accommodate how they work with Tribes.”

“Each Tribe is a little bit different in how they operate. And you might see one Tribe much more responsive versus another. And a lot of those tribes slipped through the cracks. Sometimes agencies put out a Notification of Intent, or they have something in the plans where they at some point need to consult with tribes, but the Tribe is not available or responsive. And that gets seen upon and counted as consultation. And for us, consultation has to be something that is agreed upon.”

“Often, we’ll meet as an agency to another agency, but will state that this isn’t consultation, this is purely informational, until we kind of get into the bandwidth where we’re ready to consult now, and we can move forward, hopefully. But I think we need to find ways to relax some of the more rigid policies and regulations put in place decades ago; now, we’re finding that they’re really obsolete. The way we consult now versus then is completely different. So things need to reflect that.”

“Our Tribe does get heavily involved at the legislative levels. Sometimes it takes a bill to change things. And we’ve done that, but it takes a lot of time, a lot of effort, and a lot of money. Even then, you still might have resistance from agencies because it’s a change. We don’t like change too much when it comes to these things because we get set in our ways, but you really need to be flexible with Tribes because a lot of our values do not line up with how things are structured nowadays, governmentally speaking.”

Brett Milligan: “There wasn’t a lot of tribal representation in Franks Tract. We did try to reach out; it was not at the beginning, which is also our fault. And we had trouble getting participation. That is a limitation of that project. And I appreciate it being pointed out. I saw that was a problem with that project.

“Now working on another project in the same region of the Delta called Delta Island Adaptations. We are taking a different approach. Right from the get-go, we have two indigenous tribal members from the Delta on our advisory board, so from the start, we’re trying to see how we can think about co-management. I find it’s very challenging to make sure that when you do this work, you don’t end up repeating colonial legacies or making sure that it’s mutually beneficial… So really, we’re trying to make sure that it is for their benefit.

“Much of what Matt was bringing up such as access to basket weaving materials, or having the opportunity to perform some forms of stewardship that used to be done in the Delta like burning … We are looking at that and trying to find ways to integrate that. It’s been really interesting working with [indigenous people] who are helping us, as it’s affected how we think about all our objectives. They come at things from a very different way … just a whole different approach to the landscapes of the Delta, which has informed how we’re thinking about all of that. So it’s definitely a big learning process for me.”

Jessica Law: “Matthew clearly outlined that there’s a huge gap in not just consultation but engagement with tribal communities. I see this a lot at the Water Forum. The American River below American River Parkway was and is still a place of native peoples’ cultural aesthetic – there’s so much there. We’re doing the projects mostly in the river, not in upland areas where cultural resources might exist. But still, I think there are a lot of opportunities to integrate the restoration and habitat enhancement work we’re doing with a Tribal perspective in mind.

“So in terms of process, the Water Forum, which started in the 90s and signed in 2000, had four caucuses: water, environment, business, and then civic or public, which was more groups such as the Taxpayers Association and the League of Women Voters. As we’re renegotiating the agreement, Water Forum 2.0, we’ve reformed a public caucus. We have had internal conversations about what it would look like to bring in either a tribal caucus or an outside government group. I think there are areas to explore there.

Last year at the Ancil Hoffman Park, we were doing a tremendous amount of work. The Tribal Ecological Knowledge group from the Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians visited the site. We walked the site and talked about the restoration project, which was an amazing dialogue. Since then, the woman in charge of that group, we asked her to join this stakeholder group that meets monthly. It’s called the American River Group. ARG. And it’s a stakeholder group where state and federal agencies and Water Forum members can get together, and we talk about what’s happening on the river, what the conditions are, and what the release projections are going to be for that month. And so, you know, I haven’t followed up with her since she started attending the meetings. But I think I’d be curious to hear her experiences and if she feels like that’s a good opportunity to ask questions or engage. There’s just a tremendous amount of opportunity here.”

Dr. Andrea Gerlak: “There has been a lot of research on this, and most of the research is about how people didn’t get it right; how we didn’t engage tribal communities, indigenous communities, and minority communities in good ways. So most of the scholarship is about how we’ve gotten this wrong. You could flip that and then say, this is what we got wrong, this is how you change it, or this is what it would look like. So if you think about best practices or process, people talk about who’s at the table and about the heterogeneity of tribal communities … There’s this recognition that there are diverse communities, different interests, different ways of using water, and different experiences. It’s recognizing that heterogeneity.

“It’s how you build an agenda, the content of it, the flow, how people talk, the language that you use – all of that can be inclusive to diverse kinds of people or not or can be more closed off. … It’s about engaging with tribes and different communities at the very beginning, not bringing folks in later. And it’s about asking tribal members and representatives how they want to be engaged. It does not presuppose our usual set of how we do this, but it’s sitting down and having those rich conversations about how people want to be engaged.

“There’s great scholarship around environmental justice that’s really evolved. We know that it’s about process and procedures, how you bring people together, how we distribute goods and benefits, and who wins and who loses. But over the last number of years, people have been talking about recognition and rights for tribal communities in the US. It’s about tribal sovereignty, seeing tribes as government entities equal to all of these other entities, and recognizing those rights. It’s having conversations and processes that, frankly, are different. It’s not just about bringing the tribes to the table; it’s rethinking what that table looks like and how we do our processes. And I don’t think we have best practices because we don’t do this well. And we need to be thinking about how to do it better. And that needs to be in conversation with tribes about how they want to have these conversations.”