At the June meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, Delta Lead Scientist Laurel Larsen’s report focused on the effects of temperature in the Delta.

Dr. Larsen began by noting that the weather has been hot, resulting in fish being trucked to the Delta to bypass the Delta and its warm temperatures. When the water temperature gets above 68 degrees Fahrenheit in the Delta, migrating salmon experience near-complete mortality, so trucking them around the Delta enables them to avoid this fate.

“What we’re seeing with the need to truck salmon is a consequence of the times that we’re living in,” Dr. Larsen said. “Several of the Delta’s keystone native species are at the southern extent of their ranges, and this fact makes them incredibly vulnerable to slight increases in temperature associated with climate warming.”

Knowing how temperature changes in different parts of the Delta and what those changes might be associated with can help manage the species, such as trucking salmon to the Bay or choosing a location to release fish in a reintroduction program. And suppose we know that inflows are a substantial driver of lower temperatures in parts of the Delta. In that case, reservoir operations theoretically could be modified to lower temperatures in the Delta at certain times of year that are critical to the life cycles of native species.

“This is something that’s already done with releases of water from the Shasta Dam cold water pool, as is required under the federal biological opinion for winter-run Chinook salmon,” said Dr. Larsen. “But the extent to which reservoir operations actually impact temperatures in the Delta is poorly understood. So understanding the impact of temperatures on ecosystems is a knowledge gap that falls squarely within the realm of two management needs from the 2022-2026 Science action agenda: one is to acquire new knowledge and synthesize existing knowledge of interacting stressors to support species recovery and ecosystem health, and the second is to assess and anticipate impacts of climate change and extreme events to support successful adaptation strategies.”

Dr. Larsen noted that little is known about temperature in the Delta. However, it is widely accepted that air temperatures are the dominant drivers, something we have little control over. Dr. Sam Bashevkin from the Synthesis and Decision Support Unit of the Delta Science Program has been analyzing over five decades of data collected as part of regular boat monitoring surveys conducted by the Interagency Ecological Program. Over the past few months, Dr. Bashevkin and his team have published two papers detailing this work and the preeminent journal, Limnology and Oceanography.

From the observed spatial distribution of water temperatures and their changes over time, Dr. Bashevkin fit a model that partitioned the variability and temperature into normal seasonal changes, smoothly varying spatial changes, changes due to different types of water years, and then a smooth long term trend. Effectively, the model tested whether the long-term trend of increasing temperatures could be teased out from all of the background variability due to differences in space, seasons, and different types of water years.

From the observed spatial distribution of water temperatures and their changes over time, Dr. Bashevkin fit a model that partitioned the variability and temperature into normal seasonal changes, smoothly varying spatial changes, changes due to different types of water years, and then a smooth long term trend. Effectively, the model tested whether the long-term trend of increasing temperatures could be teased out from all of the background variability due to differences in space, seasons, and different types of water years.

“The answer to that question is yes, there is a warming trend in the Delta, with water temperatures having increased on average by about 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit over the past 50 years,” said Dr. Larsen. “However, that warming trend wasn’t evenly distributed over space or time. Warming was most widespread through the estuary during the late fall to winter, which overlaps with juvenile Chinook salmon development and the spring spawning season of Delta smelt. Warming was the most rapid and northern regions that are important for fish migration and areas of tidal wetland habitat, which is a concerning challenge for management.”

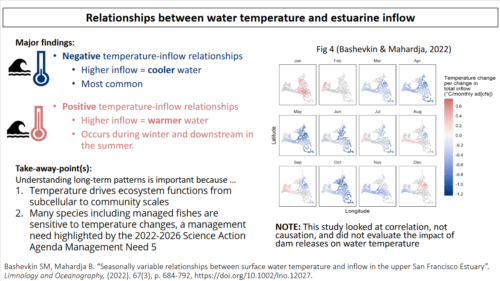

In his second study, Dr. Bashevkin combined the temperature data with Delta inflow data to evaluate the associations between the two once the background spatial and seasonal variability was accounted for. In that study, they found that the relationship between water temperature and inflow was mostly negative, which means that at times when inflow is high, water temperature tends to be low, and vice versa. These effects can be substantial, with water temperatures decreasing by up to 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit from periods of low inflow to high inflow.

In the winter, air temperatures in the Delta region are colder than water temperatures. High inflow is associated with higher temperatures in downstream regions that are more influenced by tide, possibly because during high flow years, water originating from higher in the watersheds pushes out the colder ocean water. In contrast, the colder ocean water intrudes into the Delta during low flow years.

“One important caveat is that the study doesn’t demonstrate that low inflows cause higher water temperatures,” said Dr. Larsen. “Both low inflows and high water temperatures, for example, can be a product of a hot drought, like the drought that we’re living through right now. These droughts do cause inflows to be low because of reduced precipitation and enhanced evapotranspiration. Water temperatures are driven by air temperature, and this could result in the same type of association that the study found but without requiring a causal relationship from inflow to temperature. Testing for the existence of that type of causal relationship would instead require a process-based temperature modeling study.”

“So even though this study by Dr. Bashevkin doesn’t allow us to estimate whether or by how much reservoir water releases might be able to decrease water temperatures in the Delta, it does lay a strong foundation for understanding those associations between temperature and inflows,” she continued. “And it establishes a hypothesis that inflows might, just might, be able to drive enough of a temperature shift in the Delta to make a difference for listed species. But that is something that requires further study.”

- Warming in the upper San Francisco Estuary: Patterns of water temperature change from five decades of data; Bashevkin, Mahardja, & Brown, Limnology and Oceanography, 2022

- Seasonally variable relationships between surface water temperature and inflow in the upper San Francisco Estuary; Bashevkin & Mahardja, Limnology and Oceanography, 2022.

ACTIVITIES OF THE DELTA SCIENCE PROGRAM

Delta Salinity Management Workshops

Report out on the Delta Salinity Management Workshop

(Copied and pasted from the Staff Report)

On April 26-27, 2022, the Delta Science Program convened the first in a series of workshops focused on salinity management in the Delta. The overarching goal of this workshop was to kick off a collaborative adaptive management process for evaluating long-term tradeoffs associated with alternative strategies for salinity management during droughts.

Specific goals were to (1) build toward a shared understanding of how salinity management affects different people, industries, and ecological systems; (2) identify knowledge gaps that could be filled with future research and scenario-based modeling; (3) start conversations around goals for long-term adaptive management; and (4) lay the foundation for a collaborative scenario-based modeling exercise.

The workshop had over 200 registrants, about half of whom were affiliated with California State agencies. Other registrants primarily represented federal, local, and nonprofit organizations, universities, and consultancies. Workshop discussions focused on exchanging diverse perspectives associated with salinity management in the Delta, the challenge of developing meaningful metrics of impacts, the importance of community engagement and collaboration, and the barriers to innovation and experimentation. Despite a diversity of interests, a unifying prioritization on social justice and equity emerged.

Specifically, a key takeaway was the perceived inevitability of tradeoffs and the recognition of the importance of the intentional effort to mitigate disproportionate cost burdens on vulnerable and historically marginalized communities throughout the Delta. Other discussions focused on a proposal for a demonstration exercise that will use quantitative computer models to evaluate alternative scenarios for future salinity management in the face of drought and sea-level rise. The demonstration will help identify needs and gaps and set the stage for a long-term, collaborative scenario planning and modeling process. Participants expressed a desire to relax model assumptions about how operations of the water projects are conducted and to use complementary quantitative and qualitative approaches to assess socio-economic and ecological impacts.

Workshop feedback will inform a series of meetings to be held later this year, during which the project team will seek more detailed input from stakeholders and other interested or affected parties. Pilot scenarios will subsequently be modeled and outputs are expected to be presented for discussion in the winter/spring of 2023.

Update

The long-term, collaborative planning process has begun; the modeling subgroup of the planning committee is proceeding to work with contractors to develop a proposal for doing the modeling for the demonstration exercise. They are considering and incorporating the feedback received from participants in the first workshop.

The team continues to seek feedback on the demonstration modeling exercise and the gaps and priorities to be addressed. They are engaging Delta stakeholders through a partnership with the Delta Adapts efforts and by spreading awareness of the need to better understand the concerns and needs of the impacts that salinity management will have in the future through extended drought and sea level rise. They are also developing a plan to attend other Delta stakeholder meetings to give presentations to introduce this topic and seek additional feedback.

In addition, two other working group sessions are being planned for the summer and fall that would be broadly open to the community of stakeholders and interest groups. The second workshop has been pushed back to late spring or early summer of 2023 to give more time to engage with the community and to have meaningful modeling work done that tackles some of the troublesome assumptions that are in existing models and creates tools that could be used in the longer-term planning process.

Delta Science Fellows Program

They continue to review the proposals received for the Delta Science Fellows Program. It was the largest batch of applications received in the 10+ years of the program. Review panels convened in early June evaluated the proposals.

“All of the panelists were just really cognizant of the fact that this is a really strong group of applications that we received,” said Dr. Larsen. “We’ve been having a lot of really challenging, in a good way, internal discussions to try to identify the proposals that we’re going to award funding to, and we’re in the process right now of talking to some of our funding partners and coordinating with them. But we expect to report on the award decisions and the projects at the July council meeting.”

Water data science symposium

One of the synthesis activities of the Delta Science Program is to promote platforms for data sharing, provide data analysis tools and software to the science community, and provide training and how to extract a story from data. As part of these activities, the Delta Science Program regularly coordinates with other agencies such as the USGS and State Water Resources Control Board that have a similar emphasis on data synthesis.

The California Water Data Science Symposium, hosted by the State Water Board, is an annual event that targets state scientists, academic scientists, and students to improve the collection and use of water quality monitoring data for management decisions. The event also includes a Water Data Challenge, a data hackathon aimed at collaborative problem solving using water data to answer important questions. This year’s challenge questions focused on how water data can be used to benefit human communities and promote justice and equity.

Several folks from the Delta Science Program gave presentations designed to pique interest in and awareness of the tools, resources, and data the Council has invested in making available to the community. They also proposed important questions of management relevance that could be addressed with new analyses of already available datasets using already available tools.

Link to 2022 California Water Data Science Symposium Recordings & Resources