Traditionally, stormwater was viewed as a flood management problem in which the runoff needed to be conveyed as quickly as possible away from urban areas and ultimately into waterways to protect public safety and property. Consequently, stormwater was considered a problem and not a resource.

However, in recent years, stormwater management has been receiving more attention as drought has put more pressure on water supplies, and municipal governments have been held increasingly responsible for pollutants washed from urban areas within their jurisdictions that are discharged into waterways.

In 2016, the State Water Board adopted a stormwater strategy to develop innovative regulatory and management approaches to maximize opportunities to use stormwater as a resource. At the June 21st meeting of the State Water Resources Control Board, staff updated the Board members on the Strategy to Optimize Resource Management of Stormwater (STORMS) program.

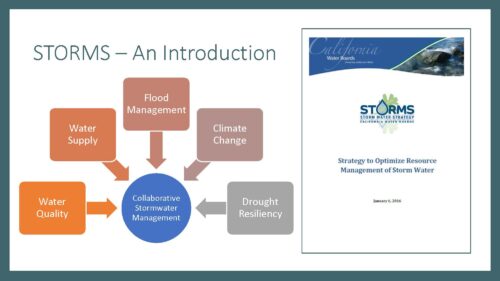

Amanda Magee, Supervisor for the STORMS unit, noted that historically, water management in California has been divided and compartmentalized into water quality, water supply, and flood control interests that span a variety of state, county, and local agencies. Stormwater touches all of these and is often perceived as a source of pollutants and a major contributor to water quality impairments.

Amanda Magee, Supervisor for the STORMS unit, noted that historically, water management in California has been divided and compartmentalized into water quality, water supply, and flood control interests that span a variety of state, county, and local agencies. Stormwater touches all of these and is often perceived as a source of pollutants and a major contributor to water quality impairments.

On the other side, population growth, climate change, and aridification are increasing pressure on the state to take immediate action and manage its water resources more effectively. These challenges represent an opportunity to redefine how California utilizes and values stormwater as a resource.

In January 2016, the State Water Board adopted the Strategy To Optimize Resource Management of Stormwater (the stormwater strategy or STORMS) to lead the evolution of stormwater management in California and advance the perspective that stormwater is indeed a valuable resource. The STORMS unit was created within the Division of Water Quality to develop policies for collaborative watershed level stormwater management and pollution prevention and to develop and oversee projects to achieve the goals and objectives of the strategy.

In January 2016, the State Water Board adopted the Strategy To Optimize Resource Management of Stormwater (the stormwater strategy or STORMS) to lead the evolution of stormwater management in California and advance the perspective that stormwater is indeed a valuable resource. The STORMS unit was created within the Division of Water Quality to develop policies for collaborative watershed level stormwater management and pollution prevention and to develop and oversee projects to achieve the goals and objectives of the strategy.

Well-conceived stormwater management actions provide multiple benefits for California communities, including improved water quality, increased water supply, increased space for public recreation, increased tree canopy, enhanced stream and riparian habitat area, as well as many other benefits. Accordingly, the stormwater strategy identifies the goals, objectives, and actions needed for the State Water Resources Control Board and the nine regional water boards to improve the regulation, management, and utilization of California’s stormwater resources.

In 2020, staff wrapped up most of the phase one projects which included identifying barriers, determining the potential for enhancing urban stormwater capture and use, and assessing uncertainties related to alternative compliance. They identified barriers to and opportunities for funding stormwater capture programs and developed recommendations to address zinc in urban receding waters.

“These projects were a great foundational start to the program and really allowed us to identify issues we didn’t initially recognize,” said Ms. Magee.

As the phase one projects were wrapping up, staff conducted outreach to stakeholders, partners, and regional boards to solicit potential project ideas for phase two of the STORMS program. From this effort, a long list of potential projects, including some originally identified in the stormwater strategy, projects identified through outcomes of phase one projects, and new projects. Those projects were then prioritized based on several factors, including feasibility, timeliness, relationship to stormwater strategy, stakeholder and regional board survey results, and State Water Board priorities.

Phase two projects

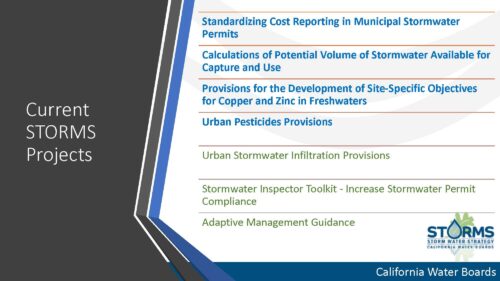

The slide shows the list of projects for phase two; the priority projects are in blue.

The slide shows the list of projects for phase two; the priority projects are in blue.

Standardizing Cost Reporting in Municipal Stormwater Permits

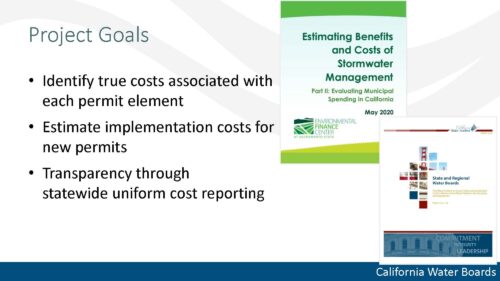

Nabiul Afrooz, a Water Resource Control Engineer in the STORMS unit, next discussed the efforts to standardize cost reporting for municipal stormwater permits.

Permits greatly vary across the state depending on local and site-specific conditions. In addition, while most permits require annual reporting of implementation costs, the reporting format specified in the permits are rarely consistent. These inconsistencies in data collection and reporting make it unclear how expenditures directly relate to specific elements in their permits. It also presents difficulties for the Regional Water Boards as they make cost considerations for new permit requirements.

“Considering all these challenges, in 2018, the state auditors highlighted a need for a statewide cost reporting guidance,” Mr. Afrooz said. “More recently, in 2020, the Office of Water programs at Sacramento State University published an evaluation of municipal spending in California. The authors concluded that the lack of standardized reporting across and even within the regions inhibits reliable estimates and confidence in observed trends.”

“Considering all these challenges, in 2018, the state auditors highlighted a need for a statewide cost reporting guidance,” Mr. Afrooz said. “More recently, in 2020, the Office of Water programs at Sacramento State University published an evaluation of municipal spending in California. The authors concluded that the lack of standardized reporting across and even within the regions inhibits reliable estimates and confidence in observed trends.”

“The goal of this STORMS project is to impart better transparency to cost reporting to developing a standardized list of cost categories and model permit language,” he continued. “Deliverables from this project build upon the statewide cost reporting guidance previously developed by the Office of Research Planning and Performance in 2019.”

At this point, staff has reviewed existing phase one and phase two permit requirements and available annual reports and prepared a draft list of cost categories. The list was shared with stakeholders, and a public workshop was held last April to seek input on the draft categories.

At this point, staff has reviewed existing phase one and phase two permit requirements and available annual reports and prepared a draft list of cost categories. The list was shared with stakeholders, and a public workshop was held last April to seek input on the draft categories.

Staff continues to engage with project stakeholders for additional feedback as the draft categories are finalized and a statewide reporting tool for cost reporting is developed. Draft model permit language along with the cost categories are anticipated to be released for public comment in spring 2023.

Calculations of Potential Volume of Stormwater Available for Capture and Use

Sahand Rastegarpour, a Water Resource Control Engineer in the STORMS unit, noted that California faces continuous water supply challenges, which are only expected to increase in the future due to higher demand, extreme droughts, climate change, and other factors. When it rains, the stormwater runoff from impervious surfaces can be used to increase and diversify California’s water supplies, so determining the potential of stormwater capture has been an objective of our STORMS programs since its inception.

Multiple reports were developed as part of phase one. A 2017 report identified the barriers to stormwater capture and use. Another report was developed with the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project, which established multiple methodologies to estimate the amount of stormwater captured and used statewide. Additionally, the STORMS program provides consistent updates to the State Water Board’s Climate Initiative.

For this project, staff developed a first-order estimate of stormwater capture on a localized scale to demonstrate the potential of capture as a new water resources effort. The next step was to compare this to other estimations and existing capture efforts in the area and use that to determine the baseline of stormwater capture and supplement future efforts.

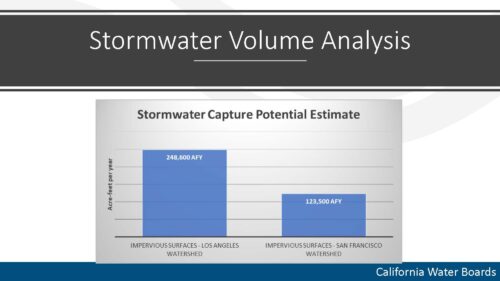

“We looked at impervious surfaces in the San Francisco Bay and Los Angeles watersheds,” said Mr. Rastegarpour. “But it’s important to know that stormwater capture is viable across the state and not just limited to the major counties we included in these studies, which were chosen because of data availability.”

Staff developed a first-order snapshot from GIS in Excel with impervious surface runoff only in the Los Angeles and San Francisco watersheds. They found approximately 250,000 acre-feet per year of stormwater capture potential for the Los Angeles River watershed and 124,000 acre-feet per year of capture potential in the San Francisco Bay watershed.

Staff developed a first-order snapshot from GIS in Excel with impervious surface runoff only in the Los Angeles and San Francisco watersheds. They found approximately 250,000 acre-feet per year of stormwater capture potential for the Los Angeles River watershed and 124,000 acre-feet per year of capture potential in the San Francisco Bay watershed.

“When comparing to some real-life estimates specifically in the central and west coast groundwater basins of Los Angeles, we approximate 54,000 acre-feet of stormwater runoff per year are currently captured and recharged,” said Mr. Rastegarpour. “Looking at initial comparisons and considering the size of the acreage with the areas involved gives us a general idea of how we are well under our potential of capturing stormwater as a resource. And we plan on diving further into these estimates with more details in our upcoming GIS story map.”

As for the stormwater potential of the overall state of California, there are estimates from the Pacific Institute and Second Nature that put stormwater capture potential anywhere from 600,000 acre-feet to 3 million acre-feet per year, depending on rainfall amounts.

“There are many aspects when estimating stormwater capture potential, and every new factor is going to present its own challenges to consider,” said Mr. Rastegarpour. “Focusing on local areas with existing stormwater capture projects could help refine those estimates. There are also more detailed models available, and we can work with different organizations to determine the best metrics for tracking, capture, and use, which isn’t just limited to volume. We can also use those new metrics to build our existing models.”

“Stormwater is going to be a significant part of California’s goal in identifying and bringing in new water resources and replacing potable water where possible,” he said.

Next steps include continuing to engage and collaborate with stakeholders and stormwater permit holders to determine what specific plans and policies will help identify where and how stormwater capture efforts should be implemented. Staff will continue to tackle projects identified in the 2017 barriers report, which includes looking at BMP efficiency, increasing data, and funding, which is often identified as a strong barrier. They are also incorporating racial equity into new studies by examining the relation to impervious surface cover and the implementation of green infrastructure projects.

Next steps include continuing to engage and collaborate with stakeholders and stormwater permit holders to determine what specific plans and policies will help identify where and how stormwater capture efforts should be implemented. Staff will continue to tackle projects identified in the 2017 barriers report, which includes looking at BMP efficiency, increasing data, and funding, which is often identified as a strong barrier. They are also incorporating racial equity into new studies by examining the relation to impervious surface cover and the implementation of green infrastructure projects.

Finally, the upcoming story map will demonstrate the significance of stormwater capture for public and legislative information. It will include informative graphics and be designed for laypeople who might not be familiar with stormwater. Staff expects to publish the story map in the coming months.

“The STORMS program understands the need for new water resources, and we’re excited to tackle the challenges and steps necessary to increase stormwater capture and use in California,” said Mr. Rastegarpour.

Site-Specific Water Quality Objectives for Copper and Zinc

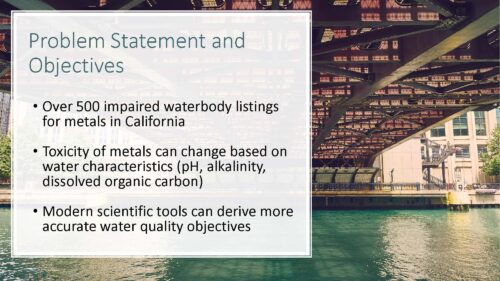

Chris Beegan, Engineering Geologist with the STORMS unit, noted that this project intends to develop a water quality control policy that describes how site-specific objectives for copper and zinc shall be developed.

“Site-specific objectives for these metals from data collection to State Board consideration can take a decade or more and are typically quite contentious due in part to a lack of consistent protocols and procedures,” said Mr. Beegan. “Metals are a frequent cause of listings in California, and the majority of those are for copper and zinc. Our existing water quality objectives, which serve as the basis for those listings, do not account for the major factors that limit metal toxicity or control bioavailability in the water column.”

“Site-specific objectives for these metals from data collection to State Board consideration can take a decade or more and are typically quite contentious due in part to a lack of consistent protocols and procedures,” said Mr. Beegan. “Metals are a frequent cause of listings in California, and the majority of those are for copper and zinc. Our existing water quality objectives, which serve as the basis for those listings, do not account for the major factors that limit metal toxicity or control bioavailability in the water column.”

In partnership with the Los Angeles Regional Board staff, they are evaluating the use of bioavailability models, such as the biotic ligand model, and the minimum data necessary to develop reliable and protective sites specific objectives. This evaluation will be used to support policy development.

“We expect the resulting policy to streamline the development of site-specific objectives while providing a more accurate assessment of metal bioavailability and improved protection of aquatic life-related beneficial uses,” said Mr. Beegan.

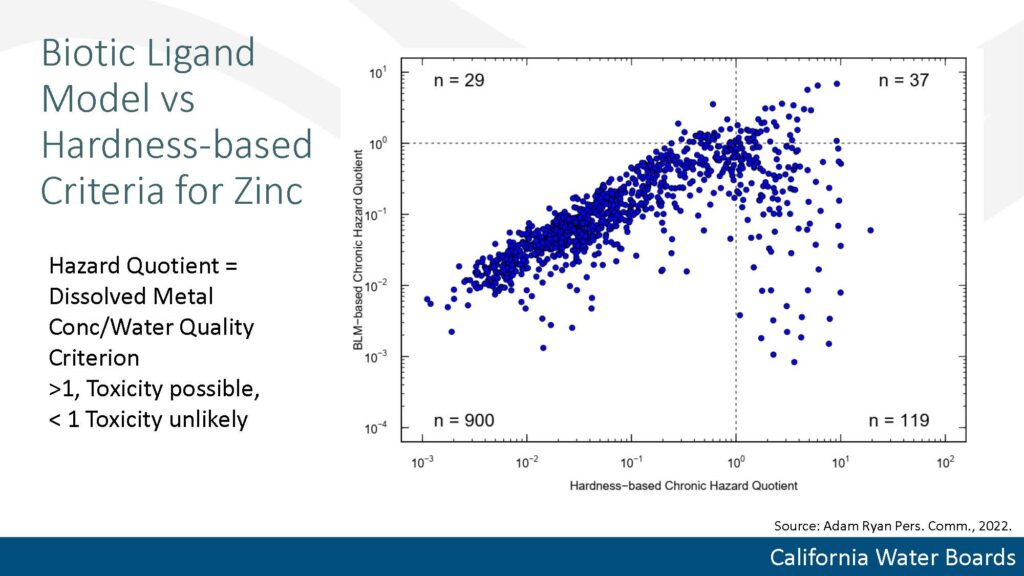

The slide shows a plot comparing the hazard quotient for the existing hardness-based criteria shown on the X-axis and the hazard quotient for the biotic ligand model-based criteria on the Y-axis. The hazard quotient is the metal concentration in the water column divided by the water quality criterion. When the concentration in the water column equals or exceeds the water quality criterion, zinc-related toxicity is possible, and the hazard quotient is equal to or greater than one. If the hazard quotient is less than one, the concentration is less than the criterion, and toxicity is unlikely. The dashed vertical line is where the hardness-based hazard quotient equals one, while the dashed horizontal line shows where the biotic ligand model-based hazard quotient equals one.

“The message here is that while the hardness-based criteria and the more sophisticated biotic ligand model use different factors to account for metal bioavailability, there is agreement for the 900 samples unlikely to be toxic shown in the lower left, as well as the 37 samples in their upper right where zinc-related toxicity as possible,” said Mr. Beegan. “However, there are 119 samples shown in the lower right and 29 samples in the upper left that illustrate how incorporating improved bioavailability models can result in different outcomes. Please note this dataset is from a variety of watersheds throughout California and not necessarily representative of urban watersheds where such projects are likely to be undertaken.”

Key issues for implementation to be addressed include ensuring that bioavailability and metal concentrations in the segment of interest are well characterized over space and time; ensuring that water quality is protected in downstream segments and reaches beyond the project boundaries, including estuarine and marine waters; and lastly, recognizing the need to reassess conditions periodically to ensure that changes in flow regime or source waters does not alter metal bioavailability over time.

Staff held a CEQA scoping meeting in February of 2022. The draft policy for public comment and scientific peer review is expected to be available in early 2023.

Urban Pesticides Provisions

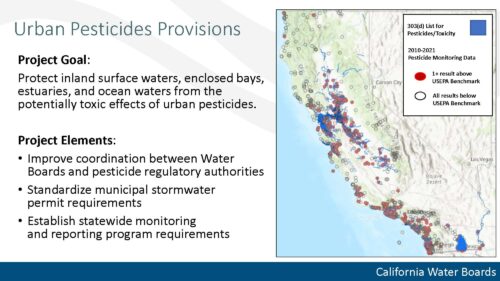

Next, Sara Huber, Water Resources Control Engineer in the STORMS unit, gave an update on the urban pesticide provisions. The provisions aim to protect inland surface waters, enclosed bays, estuaries, and ocean waters from the potentially toxic effects of pesticides applied in urban areas.

The project will achieve this goal through three project elements:

The project will achieve this goal through three project elements:

Improved coordination between the water boards and pesticide regulatory authorities: The Water Boards will continue strengthening collaborative efforts with the California Department of Pesticide Regulations and the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

Standardized municipal stormwater permit requirements for pesticide pollution prevention: For the second project element, the State Water Board would establish baseline requirements for Integrated Pest Management and community outreach that would apply to all municipal stormwater permittees. Integrated pest management programs would be elevated to a common standard that reflects lessons learned over the last decade of work. These local programs would be integral to community outreach, consisting of a series of statewide harmonized outreach campaigns designed to promote integrated pest management and influence private pest use at home and work.

Better monitoring data that can inform management actions both locally and statewide: The State Water Board would establish monitoring and reporting requirements for pesticides and pesticide-related aquatic toxicity. However, there is a need for better data, as illustrated by the map on the slide. White dots indicate sites where available pesticide results are below the United States EPA aquatic life benchmarks and may even be 100% non-detectable; red dots indicate monitoring locations with recent pesticide water quality concentrations above those same benchmarks. Impaired water bodies are shown in blue.

“The goal is to modify existing monitoring programs to reflect current urban pesticide use, better informed management actions, and evaluate the water quality impact of the provisions as a whole,” said Ms. Huber. “Staff are actively working on the monitoring program design and other major draft elements of the provisions. And we plan to have a draft package for public comment in spring of 2023.”

Non–priority projects

- The staff is currently working on a charter for the urban stormwater infiltration provisions intended to promote stormwater capture through infiltration while ensuring groundwater resources are protected.

- The stormwater inspector toolkit is an internal set of technical guidance documents for regional board inspectors to increase stormwater permit compliance through better and more efficient inspections and audits.

- The adaptive management project aims to reduce uncertainty in stormwater planning and management by developing a best practices framework for designing alternative compliance pathway monitoring programs to reduce uncertainty in stormwater permits and better inform adaptive management strategies.

Next steps

Lastly, Amanda Magee closed out the presentation with the next steps.

Phase two projects will continue for the next several years. “As we continue towards the finish line, we want to ensure that we maintain our high level of stakeholder and partner coordination,” she said. “We continue to do this through speaking engagements, stakeholder workshops, roundtable presentations, and one-on-one communication. When we start to wrap up these phase two projects and start thinking about phase three of STORMS implementation, we will initiate another extended outreach period to ensure that we engage and find project partners who we can team with to maximize our efforts and make a difference.”

The stormwater strategy is broad enough that a wide range of projects is possible; some are listed on the slide. Phase Three projects are anticipated to include infiltration provisions to protect groundwater.

The stormwater strategy is broad enough that a wide range of projects is possible; some are listed on the slide. Phase Three projects are anticipated to include infiltration provisions to protect groundwater.

“Climate change, droughts, and the continued aridification of California are a reminder that water resiliency is essential, and realizing stormwater as a resource is a huge step towards the development of new locally sourced water supplies,” said Ms. Magee. “I heard you, Chair Esquivel, mentioned earlier in the drought item that in order to maintain our water supplies, we need to unlock innovation. And I really think that the next phase of STORMS will allow us to do just that. We look forward to collaborating with all our project partners and stakeholders to identify new projects and assist in that final project selection.”

DISCUSSION / PUBLIC COMMENT PERIOD

During the discussion period, board members noted the importance of stormwater and praised the staff’s work on the program.

Jonathon Bishop, Chief Deputy Director, pointed out that the STORMS program was designed to be the counterpart of the standards program for surface waters, but there wasn’t the same level of tools developed for stormwater when it was brought into the Clean Water Act. As the team meets with stakeholders, they are learning the tools needed to better manage stormwater and improve water quality.

“This team was developed so that we’d had a place to address those, and instead of doing them in a permit by permit update approach,” he said. “So over time, what we’ve seen is that the initial STORMS projects were much broader … how do we incentivize stormwater? And now we’re starting to see more regulatory actions that improve the ability to work with stormwater. So as we move forward, I encourage you, as you’re talking to stakeholders, to forward information about what is concerning them about stormwater so that we can make sure that we fold that into our future. … I expect what will happen with stormwater, too, is that we’ll have more than we can do. And so we need to continue to refine that and identify what’s important and make sure we’re working on what’s important, and finishing what we started so that we can utilize them.”

During the public comment period, Karen Cowan, Executive Director of the California Stormwater Quality Association, gave a brief presentation.

CASQA’s vision is that California sustainably manages stormwater as an essential component of the state’s water resources that supports human and ecological needs, protects water quality, and enhances and restores our waterways. Ms. Cowan noted that sustainably means environmentally, economically, and socially sustainable.

CASQA’s vision is that California sustainably manages stormwater as an essential component of the state’s water resources that supports human and ecological needs, protects water quality, and enhances and restores our waterways. Ms. Cowan noted that sustainably means environmentally, economically, and socially sustainable.

She pointed out that public education is key to changing everybody’s perspective that stormwater is a resource, not a waste. “If something is a resource, you protect it; you take care of it. So it is fundamental not to think of it as toxic soup, as the language has been from the dawn of time and stormwater permitting, but it is a very valuable resource.”

Ms. Cowan agreed that funding is important. “We are in desperate need of significant funding. We talk about precipitation changing to rain as opposed to snow. This is re-plumbing California and really thinking of our future. It’s going to take massive investment from the state as well as the federal government. Adding to our challenge is Prop 218 that it’s also locally prohibited for almost everybody. So we have a big need and a big challenge ahead of us.”

“Our needs are infinite; our resources are negligible,” she said. “It’s hard to get resources when that’s the numbers you give people. … We are looking to find dedicated funding sources because, again, without dedicated funding, it is really hard to do massive infrastructure projects with a random grant here, a random grant there. And we have barriers to the State Revolving Fund because if you don’t have dedicated funding, it’s really hard to access that state revolving funds. So these barriers to funding build on top of each other.”

Board member Laurel Firestone asked Ms. Cowan about funding. Is it primarily the State Revolving Fund, or are there additional funding sources?

Board member Laurel Firestone asked Ms. Cowan about funding. Is it primarily the State Revolving Fund, or are there additional funding sources?

Ms. Cowan said there’s not much funding available. A new program at the EPA was developed a few years ago, but the underlying legislation was written more for combined sewer systems, which isn’t how urban infrastructure in the west developed. They worked with DFA and were able to access some funding, but there isn’t any more funding at this time.

Mr. Bishop noted that almost all of the state funding for stormwater has come through grants from ballot propositions. Ms. Cowan noted that some funding has come through the IRWM program, but very little.

“We try to get creative, wherever we can make a nexus,” said Ms. Cowan. “But it’s hard to run programs or do big meaningful work when you’re trying to backbend into find partners … for stormwater, we need really dedicated funding.”

Sean Bothwell, Executive Director for the California Coastkeeper Alliance, said the STORMS team has been terrific to work with and appreciates their efforts. Still, he did have some suggestions for improvements.

He found the phase one project results were ‘a little underwhelming.’ There seemed to be a lot of excitement around the two committees working on removing technical and funding barriers to stormwater capture. But after the white papers were developed, he didn’t see a lot of follow-through. He acknowledged that as the chair of the funding subcommittee, he could have done a better job, but he didn’t have the capacity.

The stakeholders in the subcommittee were interested in a lot of things, but water board staff at the time wanted to focus on what the Water Board’s role was. The second round of projects was decided without the same type of collaboration as the original STORMS strategic planning document, and there’s not much for environmental groups to get excited about. He feels there was a divergence from treating stormwater as a resource and a lot more focused on miscellaneous regulatory tools; they don’t seem to be focused on treating stormwater as a resource.

The stakeholders in the subcommittee were interested in a lot of things, but water board staff at the time wanted to focus on what the Water Board’s role was. The second round of projects was decided without the same type of collaboration as the original STORMS strategic planning document, and there’s not much for environmental groups to get excited about. He feels there was a divergence from treating stormwater as a resource and a lot more focused on miscellaneous regulatory tools; they don’t seem to be focused on treating stormwater as a resource.

Mr. Bothwell said there were two pathways for where he sees the STORMS program going in the future. The first is that the water board can continue down the path of developing these regulatory projects, but if so, he recommends disbanding the implementation committee and having more briefings, both internal briefings, and external public workshops, and having better transparency around the projects. The second is to return to STORM’s original intent to treat stormwater as a resource. This pathway can and should be more collaborative with projects everyone can get behind and support.

“We’re not going to ever all of us agree on compliance programs, but we can all agree that we need to remove barriers to stormwater funding,” he said. “So I have three general proposals for future projects. One is to focus on implementing the recommendations from the white paper on technical barriers to stormwater capture. There were a lot of recommendations in there, but I haven’t heard a lot of follow-up on actions since it was published. Two, a renewed stormwater funding subcommittee led by your staff instead of me, but includes projects outside of the Water Board’s silo. And then three, focus on projects to better achieve cross permittee collaboration.”

Mr. Bothwell summed up his remarks by saying, “We can continue to go down the STORMS current path, but there needs to be a lot more oversight and transparency going forward. Or focus on projects that all stakeholders get behind and be excited about projects that advance stormwater capture as a resource, while also helping permittees come into compliance rather than avoiding compliance.”

- Strategy to Optimize Resource Management of Stormwater (State Water Board)

- Stormwater Program (State Water Board)

- California Stormwater Quality Association website