Dr. Gerald (Jerry) Meral is the director of the California Water Program at the Natural Heritage Institute. He works on funding for California water, Delta infrastructure, and a variety of other California water programs. He formerly served as Deputy Director of the California Department of Water Resources, Deputy Secretary of the California Natural Resources Agency, Executive Director of the Planning and Conservation Director, and Staff Scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund.

Dr. Gerald (Jerry) Meral is the director of the California Water Program at the Natural Heritage Institute. He works on funding for California water, Delta infrastructure, and a variety of other California water programs. He formerly served as Deputy Director of the California Department of Water Resources, Deputy Secretary of the California Natural Resources Agency, Executive Director of the Planning and Conservation Director, and Staff Scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund.

I remember Jerry Meral from the Bay Delta Conservation Plan meetings (one of the precursors to the current Delta Conveyance Project) which he presided over. My coverage of those meetings back in 2013 was the kickoff for Maven’s Notebook as it exists today. So I asked Jerry Meral about the current Delta Conveyance Project, the voluntary agreements, and the projects he is currently working on.

Question 1: What do you think is the biggest threat to California water?

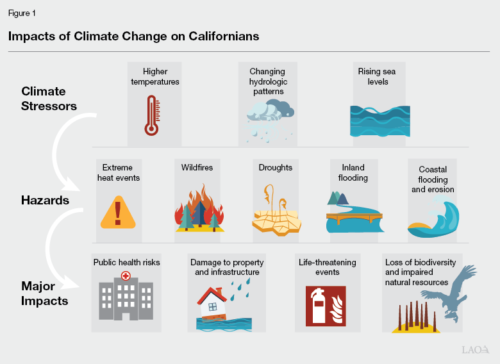

This is undoubtedly climate change. It will affect California in at least the following ways:

Conversion of snow to rain. This will severely reduce water supply by requiring larger winter floods to be detained and then passed through large reservoirs like Shasta, Oroville, Folsom, New Melones, Don Pedro and so on. It is likely that flood reservations in these and other reservoirs will have to be increased, and it will become harder and harder to refill these larger flood reservations since little snow will be left upstream in the spring. This will reduce the water supply, hydroelectric, recreational, and cold water benefits of these reservoirs.

Conversion of snow to rain. This will severely reduce water supply by requiring larger winter floods to be detained and then passed through large reservoirs like Shasta, Oroville, Folsom, New Melones, Don Pedro and so on. It is likely that flood reservations in these and other reservoirs will have to be increased, and it will become harder and harder to refill these larger flood reservations since little snow will be left upstream in the spring. This will reduce the water supply, hydroelectric, recreational, and cold water benefits of these reservoirs.

The millennial drought is bringing into question the continued value of Lake Powell. Surface evaporation and bank storage depletions may soon outweigh the fading water storage benefits of that reservoir.

Sea level rise means most Delta islands will be inundated, probably before the end of the century. Even before then, increased hydrostatic pressure due to sea level rise will force water under the levees into Delta island interiors, reducing their value for agriculture, and possibly making levees harder to maintain. When the islands fail and the Delta becomes a seawater extension of San Francisco Bay, export of water from the Sacramento River to the state and federal pumps will be impossible. This points out the urgent need for as large a facility as possible to move water safely from the Sacramento River directly to the pumps. This project should be implemented as quickly as possible. Twenty percent of California’s water supply usually comes from the Delta. It could never be replaced.

The millennial drought we are in, undoubtedly exacerbated by climate change, will force increased use of recycled wastewater, and desalination in certain locations. Lawns will soon be a thing of the past in California, and agriculture will increasingly convert to higher value crops due to water scarcity.

Fish species that rely on high flows will be increasingly challenged.

New water storage facilities seem attractive, but only those which can still be operated economically under the expected changes in river hydrology and precipitation patterns should be considered. The only ones which might prove economical will be those which capture the much larger winter flows from the Cascades and Sierra in off-stream storage reservoirs without flood reservations.

Innovation is the key to water survival. Using winter flood waters to refill groundwater basins can work on farmland without damaging crops. This practice needs to spread throughout the San Joaquin Valley. Treated wastewater should not be allowed to flow to the ocean, except to maintain streamflow.

Question 2: The state recently released an MOU for a voluntary agreement for the Sacramento Valley that promises water and habitat restoration. What do you think of this agreement? Is it enough? What do you think it would take for a voluntary agreement to be successful?

Certainly the agreement with the Sacramento Valley water rights holders is a step forward. Given the tenure and volume of their water rights, and their longstanding work with fish and waterfowl interests, it is not surprising that the agreement was reached. Unfortunately, due to the climate change impacts discussed above, the agreement will not be enough, since the temperature of released water will increase, and the allowable winter storage volume in the reservoirs will decrease due to needed increased flood reservations. It is likely that to sustain fish and waterfowl populations and to meet even modest Delta needs, farmland will have to be taken out of production. The state has made a start at paying for land conversion, but markedly larger funds will be needed in the future.

The San Joaquin River situation is much worse, although changes in flood reservations will come more slowly there due to the higher elevations in the Sierra. But sustaining anadromous fish populations will require a lot more water than the water rights holders have been willing to give so far. We can expect continued and even escalated conflict between water rights holders, state and federal regulators, and nonprofit groups.

Question 3: The environmental documents for the Delta Conveyance Project will be released this summer. The project has come a long way from the Bay Delta Conservation Plan and the California Water Fix. This is at least the third Delta conveyance project that you’ve seen the state propose. It has been somewhat downsized and has been rerouted it to reduce impacts to the Delta. Do you think this is the project that will get built?

Actually, this is my sixth round on Delta conveyance. There was the old through Delta (prior to 1970), the Peripheral Canal (1975-1983), Duke’s Ditch (1984), the BDCP tunnels/Water Fix (2 tunnel sizes, 2000-2018), and now the single tunnel.

Some tunnel opponents act out of simple self interest (Delta landowners), or are climate change deniers (see earlier discussion). But DWR and the SWP contractors have responded to legitimate concerns, and continually improved the design. I think the currently proposed facility will be constructed, perhaps with some additional improvements and modifications. It really is too small, but more capacity can be added as needed. The intake will have to gradually move upstream, probably to near the mouth of the Feather River.

Question 4: Tell me about your work with Yellow Starthistle and groundwater.

Yellow Starthistle (YST) covers more than 8 million acres of California, especially in the Sacramento Valley watershed. It is deep rooted (2 meters) compared to other annual grasses. It severely depletes groundwater. A study by MWD showed water depletions in Sacramento River tributaries which could be linked to YST.

I asked the state and federal water contractors, UC Davis, Yuba County Water Agency and others to fund a scientific study of this problem. Led by Prof. Joe DiTomaso (an internationally known invasive plant researcher from UC Davis) and Mike Deas of Watercourse Inc, with help from UC Davis, we created 4 test plots of several acres each on land owned by Bruce Rominger in Yolo County. We removed YST from 2 plots, and left it on the two control plots. We found that removal of YST improves groundwater storage by .1-.25 acre feet per acre, depending on the water year type. This means that hundreds of thousands of acre feet of water can be saved in the Sacramento Valley groundwater for a nominal cost (far less than any other new water supply, including water conservation). This water would make its way to the river.

The next step will be to ask water agencies and landowners to implement a much larger program of YST removal. The final report is now available: to get a copy send me an email at jerrymeral@gmail.com.

RELATED ARTICLE: Knocking Out Yellow Starthistle Can Boost Groundwater Supplies

Question 5: What other projects are you working on? How are you spending your time these days?

I have qualified an initiative at the Inverness Public Utility District which will be on the ballot this fall. It provides funding for wildfire prevention and improved water conservation and supply. I am also helping IPUD with a proposal to purchase water in the Central Valley through Marin Municipal Water District. The water would be conveyed by exchange via EBMUD, MMWD and North Marin Water District facilities.

I am working to bring beavers back to Marin County to improve water supply, groundwater recharge, restore fish and wildlife habitat, and help control fire in the riparian zone. I am also working to create a wildlife crossing for newts and other amphibians on a road in northern Marin County.

I am a volunteer with Point Reyes National Seashore, and have removed tens of thousands of broom and other invasive plants. I also serve on the boards of the Inverness Foundation, Fire Safe Marin, and the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin. I also volunteer with Activate America, which is trying to preserve Democratic majorities in the House and Senate.

I try to leave some time for hiking, backpacking, rafting and kayaking (sadly, without my kayaking buddy Jonas Minton).