Written exclusively for Maven’s Notebook by Robin Meadows

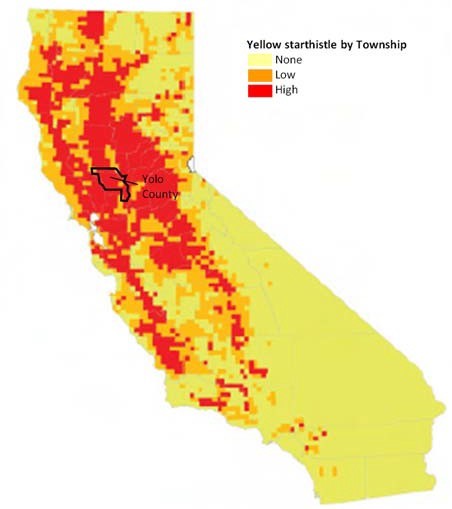

The litany of harms from yellow starthistle, California’s most aggressive invasive weed with as many as 15 million acres infested, ranges from crowding out native plants to becoming so spiny livestock stop eating it. New research adds sucking the land dry to that list.

“Yellow starthistle creates artificial drought,” says UC Davis weed specialist Joseph DiTomaso, who co-led the study.

DiTomaso first suspected yellow starthistle of being a water hog 20 years ago, when he noticed that lands overrun by this noxious weed had no oak seedlings. He surmised this was because yellow starthistle sinks its roots astonishingly deep into the soil — up to eight feet compared to about 1.5 feet for annual grasses — and drinks all the water it can reach.

DiTomaso first suspected yellow starthistle of being a water hog 20 years ago, when he noticed that lands overrun by this noxious weed had no oak seedlings. He surmised this was because yellow starthistle sinks its roots astonishingly deep into the soil — up to eight feet compared to about 1.5 feet for annual grasses — and drinks all the water it can reach.

“So we thought, ‘if we get rid of yellow starthistle, will that increase water deeper in the soil and runoff into streams?’” DiTomaso says, whose collaborators included colleagues at UC Davis and Davis-based consulting firm Watercourse Engineering.

To find out, the team studied how yellow starthistle control affects water yields at a ranch in Yolo County, focusing on four small watersheds or basins that collectively covered about 30 contiguous acres. At the outset all four basins had dense stands of yellow starthistle, and two were treated with a broadleaf herbicide while two were left untreated. The researchers then tracked factors including soil moisture, precipitation, surface runoff, and plant diversity in the basins over five years.

The results confirmed their expectations. “Where yellow starthistle is controlled, there’s deep soil moisture,” DiTomaso says. At depths beyond annual grass roots and during the wettest year in the study period, treated basins held a lot more water — 0.25 acre-feet per acre — than untreated basins. An average California household uses up to an acre-foot of water annually.

The results confirmed their expectations. “Where yellow starthistle is controlled, there’s deep soil moisture,” DiTomaso says. At depths beyond annual grass roots and during the wettest year in the study period, treated basins held a lot more water — 0.25 acre-feet per acre — than untreated basins. An average California household uses up to an acre-foot of water annually.

Yellow starthistle infests millions of acres in the Sacramento Valley, so all told the water supply could jump hundreds of thousands of acre-feet in a wet year. DiTomaso is far from being surprised at this magnitude of water savings because it’s in line with earlier small-scale projects, with test plots on the order of a few square meters.

In fact, if anything DiTomaso thinks the water yield boost is likely to be an underestimate. The test basins were grazed more lightly than he would have liked, partly because fencing made the logistics of livestock access a challenge. Grazing decreases grasses, which increases sunlight penetration and so yellow starthistle. “If we’d had heavy grazing, there would have been even more yellow starthistle in the untreated plots,” DiTomaso explains. “That would have made the differences in water supply even greater.”

While broadleaf herbicides spare grasses, this treatment does kill legumes such as clovers and vetches in addition to the target nonnative weed. But this is just in the short term. The key is to treat with herbicides two years in a row and then take a year or more off. Legumes will bounce back during the third year thanks to hard-coated seeds that persist in soil for half a century. In contrast, yellow starthistle seeds perish after just a few years in the ground. “In the third year, 98% of them are gone,” DiTomaso says.

Now happily retired, DiTomaso has no plans to do any follow up work on this project himself. “It’s 100 degrees in the summer, and you’re walking up and down hills and bending down thousands of times a day to survey plants,” he says. “It’s kind of brutal.”

Still, a fellow team member dreams of showcasing their findings on the yellow starthistle-plagued ranch of a well-known person they’d rather not name at the moment. And if this person said yes?

“I’d do it,” DiTomaso says without missing a beat.

For a copy of the report or other questions, email Jerry Meral at jerrymeral@gmail.com.