The environmental documents, due mid-summer, are about 3200 pages plus appendices

In April of 2020, the Delta Independent Science Board (DISB) submitted a public comment to the Department of Water Resources on the Notice of Preparation on the Delta Conveyance Project, indicating their intention to review the environmental impact report (or EIR) and highlighting areas from previous reviews on the Delta conveyance that DWR should consider in preparing the document. The DISB has received updates previously from DWR in August 2020 and January 2022 on the progress of the documents.

At the June meeting of the DISB, DWR staff provided another update on the progress of the environmental documents, which are anticipated to be released mid-summer for public review and comment.

DWR Director Karla Nemeth began the series of presentations with some introductory remarks and background on the project. The State Water Project, constructed in the 1960s, has long contemplated the notion of diverting water from intakes in the North Delta and routing water around the estuary for purposes of human consumption. The idea has taken many twists and turns over the decades. The Delta Conveyance Project is the latest iteration of a project that began in the mid-2000s.

Ms. Nemeth described the Delta as the linchpin in the State Water Project, which has storage facilities north of the Delta, pumping facilities in the Delta, and hundreds of miles of aqueducts that deliver water to water users in the Bay Area, in the Central Valley, the Central Coast, and down to Southern California and San Diego County. So it’s an important piece of the water supply for 27 million Californians.

“With the ongoing and accelerated effects of climate, I think this project is becoming more and more vital to not only the State Water Project, but the way in which it supports other important investments California needs to make, particularly as it relates to managing groundwater basins sustainably and significant investments in recycled water so that we can move California to a position where it can weather deepening droughts that we know are coming with the onset of climate change,” said Ms. Nemeth.

The project is essential to adapt to the more extreme hydrologic future anticipated for California, Ms. Nemeth said, pointing out that 2022 is proof that it’s possible to have intense storm events amid an acute drought. So the ability to divert water in the northern part of the Delta and convey it through tunnels to the south Delta facilities will enable the State Water Project to operate more flexibly in response to extreme hydrologic events. Another purpose of the Delta Conveyance Project is to help the State Water Project avoid significant outages due to an earthquake event in the Delta.

The project is essential to adapt to the more extreme hydrologic future anticipated for California, Ms. Nemeth said, pointing out that 2022 is proof that it’s possible to have intense storm events amid an acute drought. So the ability to divert water in the northern part of the Delta and convey it through tunnels to the south Delta facilities will enable the State Water Project to operate more flexibly in response to extreme hydrologic events. Another purpose of the Delta Conveyance Project is to help the State Water Project avoid significant outages due to an earthquake event in the Delta.

Governor Newsom, three years ago, directed the Department of Water Resources to pursue a project that was a single tunnel project, much smaller than previous iterations. So the Department began working on new environmental documents, especially focusing on the conceptual engineering, which Ms. Nemeth acknowledged was not well developed in earlier iterations of the project.

The Department also took a hard look at the routing of the project and the construction impacts on communities in the Delta. Ms. Nemeth acknowledged that the project fundamentally supports water users unaffected by its construction or operations. As a result, this has led to significant changes to either eliminate or dramatically reduce those impacts.

The Department has worked more intensively on community engagement, including disadvantaged communities and tribes. And there are new obligations, such as tribal consultation under AB 52. There were also lessons learned from the previous project about environmental justice and the outreach needed to develop a project responsive to those communities. The Department has also developed a community benefits program, separate from CEQA, which identifies ways the project can bring lasting community benefits to the areas in and around the Delta.

“This year was a stark example of the fact that we can have very intense dry conditions punctuated with intense storm events,” said Ms. Nemeth. “It can collectively continue to be an extremely dry year. But that doesn’t mean it won’t rain in California. So a big part of California’s strategy to become more climate-resilient is to move water during those very intense storm events so that we have more water in storage to enable us to survive better during drought years.”

“We also know that during drought years, there tend to be very intense pressures also on aquatic ecosystems,” she continued. “Our ability to move water when it is wet enables us to leave more water in the system when it’s dry, or at a minimum, really lessen the conflict that we experienced collectively in California of having enough water to support our communities and our economy and our ecosystem.”

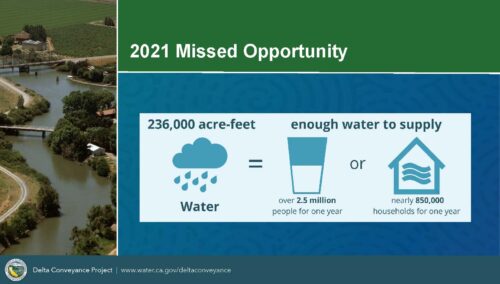

As an example, in 2021, Ms. Nemeth recalled how there were intense record-breaking storm events in December that were followed by three bone-dry months, by far, the driest wet season on record.

As an example, in 2021, Ms. Nemeth recalled how there were intense record-breaking storm events in December that were followed by three bone-dry months, by far, the driest wet season on record.

“If we had this Delta Conveyance Project in place with operating criteria as we’re proposing, we could have safely moved about 236,000 acre-feet of water simply by taking advantage of the new intakes,” she said. “One of the challenges we have, when we get a big storm in the early part of our wet season, is we turn down the pumps because we don’t want to disrupt initial cues around migration that happen with these sort of early storm events. We also don’t want to bring turbidity down into the southern part of the Delta. And that is just a key thing that additional intakes can avoid that has a material effect during these large storm events, in terms of moving water past the Delta and into storage for use later in the season.”

The project purpose as articulated in the Notice of Preparation is to modernize the aging SWP infrastructure in the Delta to restore and protect the reliability of SWP water deliveries in a cost-effective manner, consistent with the State’s Water Resilience Portfolio. The project objectives are to address sea level rise and climate change, minimize water supply disruption due to seismic risk, protect water supply reliability, and provide operational flexibility to improve aquatic conditions.

“Our objectives are to address sea level rise and climate change effects on the State Water Project,” said Ms. Nemeth. “We also want to minimize the water supply disruption that could result from an earthquake in the Delta or its environment. We do want to protect water supply reliability. As a general matter, the State Water Project and the Department of Water Resources certainly understand that with the future climate, the temperature is going to add an additional demand on the water that we manage for communities, fisheries, and the economy in California. There’s no question that with rising temperatures, we will have a higher evaporative demand. So this project itself is about working within that context to make the supplies that we do have available to us to move more reliably through our system. Then finally, we do want to enable some operational flexibility that will actually help us improve aquatic conditions.”

“Our objectives are to address sea level rise and climate change effects on the State Water Project,” said Ms. Nemeth. “We also want to minimize the water supply disruption that could result from an earthquake in the Delta or its environment. We do want to protect water supply reliability. As a general matter, the State Water Project and the Department of Water Resources certainly understand that with the future climate, the temperature is going to add an additional demand on the water that we manage for communities, fisheries, and the economy in California. There’s no question that with rising temperatures, we will have a higher evaporative demand. So this project itself is about working within that context to make the supplies that we do have available to us to move more reliably through our system. Then finally, we do want to enable some operational flexibility that will actually help us improve aquatic conditions.”

Aquatic resources approach

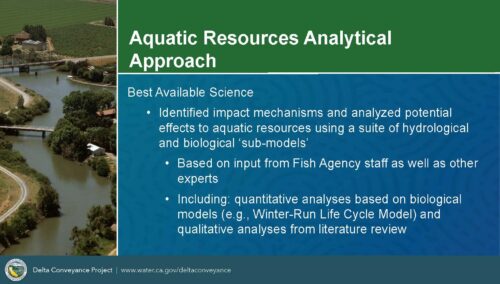

Dr. Lenny Grimaldo then briefly discussed the approach to analyzing aquatic resources. He began by saying that upfront, the Department considered how to minimize impacts, and to that end, the diversion was developed with the smaller capacity split between the two intakes to reduce the effects on fisheries. The Department also put together a committee to consider different screening technologies available; they decided on a Tee-screen technology that will reduce the footprint and provide an effective barrier to minimize fish entrainment as they move down the river.

Operational criteria are being developed that would minimize potential effects, including focusing mainly on the use of the intakes during excess conditions, developing approach and sweeping velocity restrictions to minimize potential impacts at the intake screens, and establishing bypass flow criteria and pulse protection to further restrict diversions based on flows in the Sacramento River. They are also focusing on operations during the daytime, as new research suggests that fish move at night.

Dr. Grimaldo noted that it’s not just the hydrology that will change; species will respond differently to different water temperatures and differences in the way that water moves through the system, so it will be important to keep focused on the best available science as it emerges through project implementation.

Dr. Grimaldo noted that it’s not just the hydrology that will change; species will respond differently to different water temperatures and differences in the way that water moves through the system, so it will be important to keep focused on the best available science as it emerges through project implementation.

The Department is also proposing mitigation measures to offset impacts of both construction activities and operational effects; these include channel margin habitat and tidal marsh restoration to mitigate for changes in flows that result from the North Delta diversion and project operations.

“What’s going to be really important as we move through with project implementation is adaptive management and our ability to address uncertainty,” Dr. Grimaldo said. “With climate change, we expect species to respond differently to changes in the ecosystem. So we need to keep focused on the new science that emerges and how we’re going to build this into our management decisions. Having a robust monitoring program and adaptive management program to compare and characterize the baseline versus the with-project conditions is going to be important. And we know that this is in the wheelhouse of the DISB.”

How climate change will be incorporated into the analysis

Andrew Schwarz, State Water Project Climate Action Advisor at DWR, then discussed how the documents will address climate change.

Andrew Schwarz, State Water Project Climate Action Advisor at DWR, then discussed how the documents will address climate change.

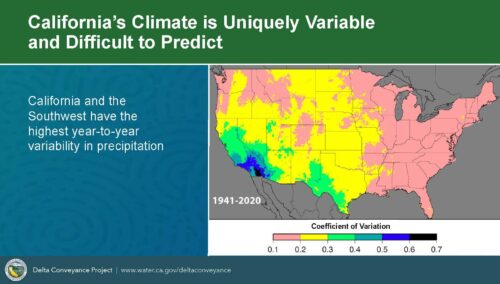

The first thing to understand about California’s hydrology is that it is uniquely variable and difficult to predict. The graphic shows the coefficient of variation of annual precipitation across the country. The yellow and pink have a lower variability; the blue, green, and black colors indicate a higher degree of year-to-year variability in precipitation.

“That’s part of the core of what we’re doing with managing water year to year in California, and climate change really makes this worse,” said Mr. Schwarz. “This project is part of our way to deal with that increasing variability.”

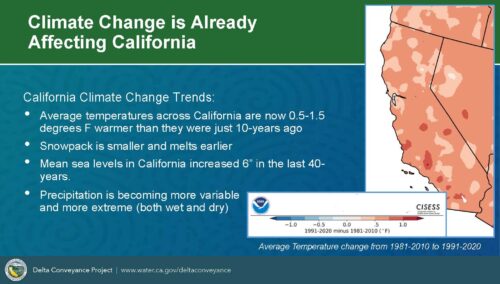

He said that climate change isn’t in the future; it’s already here. Temperatures are already .5 to 1.5 degrees warmer; the snowpack is smaller and melts earlier. The runoff is coming earlier in the season when the reservoirs are typically operated for flood protection, so we’re unable to capture that earlier runoff. Mean sea levels in California have increased six inches or more in the last 40 years, which means we have to release a little bit more water from storage every year just to repel that salinity and keep the Delta fresh. Precipitation is becoming more variable and more extreme.

He said that climate change isn’t in the future; it’s already here. Temperatures are already .5 to 1.5 degrees warmer; the snowpack is smaller and melts earlier. The runoff is coming earlier in the season when the reservoirs are typically operated for flood protection, so we’re unable to capture that earlier runoff. Mean sea levels in California have increased six inches or more in the last 40 years, which means we have to release a little bit more water from storage every year just to repel that salinity and keep the Delta fresh. Precipitation is becoming more variable and more extreme.

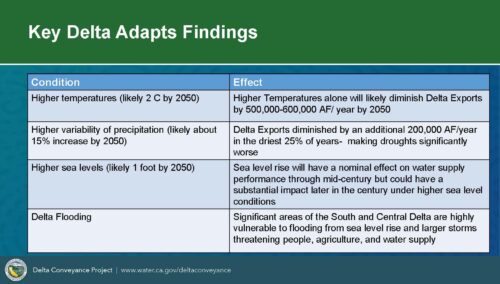

The Delta Adapts study from the Delta Stewardship Council had some key findings on water supply and flood impacts for the Delta. Temperature change alone increases demand and reduces water supply; the study estimated Delta exports would be decreased by 500-600,000 acre-feet per year by 2050 just based on temperature increases.

The Delta Adapts study from the Delta Stewardship Council had some key findings on water supply and flood impacts for the Delta. Temperature change alone increases demand and reduces water supply; the study estimated Delta exports would be decreased by 500-600,000 acre-feet per year by 2050 just based on temperature increases.

The change in variability of precipitation by 2050 really hits in the driest 25% of years. “Without additional infrastructure like Delta conveyance, and storage, we can’t store the additional water that comes in those wet years,” said Mr. Schwarz. “But we get extra hurt by those years that are drier and more dry than they would have been without climate change. And that’s another 200,000 acre-feet.”

“Sea level rise is a chronic impact that drives down our storage and really hits hard when we have very dry years; we can have shortages of water because we’ve entered those droughts with lower storage levels and less protection,” he continued. “Significant areas of the South and Central Delta are highly vulnerable to flooding from sea level rise and larger storms. The Delta is a key cog, the center hub of the water supply system. And that flooding threatens not just people and agriculture but our water supply system. This project really helps to address that.”

In terms of how climate change will be incorporated into the environmental documents, CEQA requires an analysis of the proposed impacts on the environment. Those sections will discuss how the project’s energy use and pumping of water contribute to greenhouse gas emissions and how that contributes to the continuing problem of climate change through emissions. It will also include environmental impacts that could worsen with a warmer future climate or a changed hydrologic climate.

What CEQA does not require is an analysis of climate change impacts on the proposed project; however, Mr. Schwarz said the document will include a discussion of how the project would function in a warmer world with changed hydrology and how the project help to adapt those conditions.

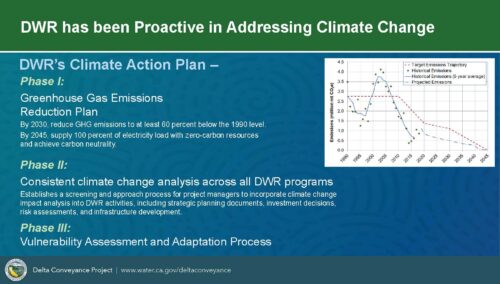

The Department has been proactive in adapting to climate change; they have had a climate action plan since 2012 that includes a goal to be carbon neutral by 2045. He noted that even with the construction and operation of the Delta Conveyance Project, the Department is still on track to meet that goal.

The Department has been proactive in adapting to climate change; they have had a climate action plan since 2012 that includes a goal to be carbon neutral by 2045. He noted that even with the construction and operation of the Delta Conveyance Project, the Department is still on track to meet that goal.

The second phase of the Climate Action Plan calls for consistent climate change analysis across all DWR programs and projects. He noted that the project has been analyzed within the DWR framework, so it is consistent with other projects and meets the Department’s rigorous standards for the best available science and consistency.

The third phase is the vulnerability assessment completed a couple of years ago. The Delta Adapts study built on some of the findings and includes an adaptation process that recognizes we will have to continually adapt to changing conditions.

“It’s not just one plan that sits on the shelf, and you do a bunch of things, and then you’re done,” said Mr. Schwarz. “It’s a process where we will have to continue to evaluate and add pieces to our infrastructure and actions and activities over time. So this is really part of that silver buckshot, not silver bullet approach.”

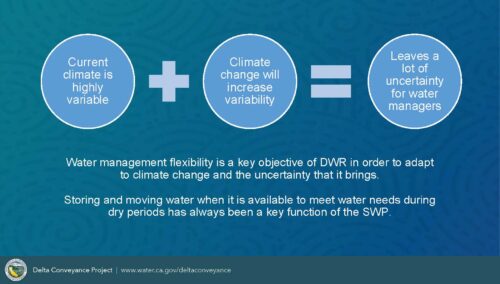

So, summing up, California’s current climate is highly variable, and climate change will increase that variability and the difficulty of managing the system. So that leaves a lot of uncertainty for water managers and water management in the face of climate change. Flexibility is a key objective to function and bring services and water to the people of California.

So, summing up, California’s current climate is highly variable, and climate change will increase that variability and the difficulty of managing the system. So that leaves a lot of uncertainty for water managers and water management in the face of climate change. Flexibility is a key objective to function and bring services and water to the people of California.

“This project really fits in with the core function of the State Water Project, which has always been storing and moving water when it’s available to meet water needs during dry periods throughout the state,” said Mr. Schwarz.

Modeling

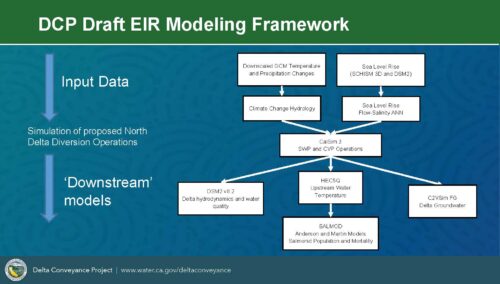

Next, Amardeep Singh, Supervising Engineer at DWR, gave a brief overview of the different models and methods being used to analyze the project. The graphic shows some of the models being used; at the center is the Cal Sim 3 model, which simulates the State Water Project and Central Valley Project operations, including the proposed North Delta diversions.

Next, Amardeep Singh, Supervising Engineer at DWR, gave a brief overview of the different models and methods being used to analyze the project. The graphic shows some of the models being used; at the center is the Cal Sim 3 model, which simulates the State Water Project and Central Valley Project operations, including the proposed North Delta diversions.

The hydrological inputs to Cal Sim include existing conditions based on historical hydrology; for the climate change scenario, they use hydrology generated based on the projected changes in temperature and precipitation from the climate models. Cal Sim uses flow-salinity relationships, which have been developed for existing conditions and the future scenario with sea level rise at 2040.

The output from Cal Sim 3 is input into a series of different models. One of those is DSM 2, which models hydrodynamics and water quality in the Delta; this model is used for existing and future conditions at 2040 with and without the project.

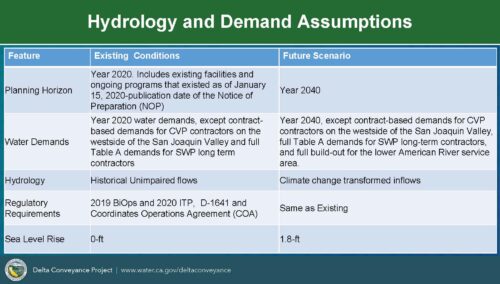

The chart shows the high-level assumptions for existing conditions and the future scenario that considers changing hydrology. The regulatory baseline is based on the existing biological opinions and incidental take permit. Sea level rise for the future scenario at 2040 is 1.8 feet, which is an extreme projection based on Ocean Protection Council guidance released in 2018.

The chart shows the high-level assumptions for existing conditions and the future scenario that considers changing hydrology. The regulatory baseline is based on the existing biological opinions and incidental take permit. Sea level rise for the future scenario at 2040 is 1.8 feet, which is an extreme projection based on Ocean Protection Council guidance released in 2018.

To determine the climate change hydrology for the 2040 scenario, they started with 32 Global Circulation Models (GCM) based ensemble scenarios from the Fifth Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5) archive. Then they selected ten available climate models that DWR’s climate change advisory group recommended as suitable for planning studies in California.

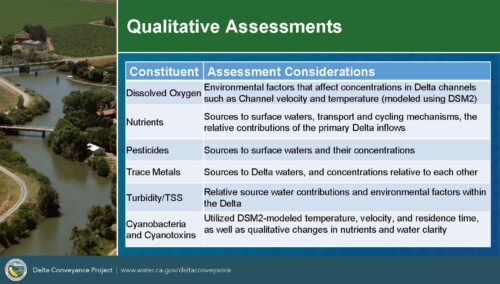

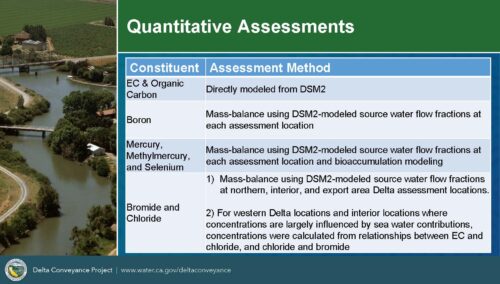

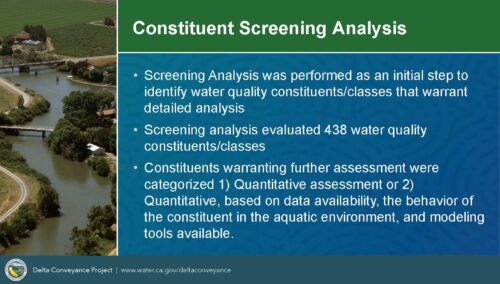

For water quality, the first step is the screening analysis, which identifies the constituents of concern that warrant detailed analysis. A list was developed with more than 438 water quality constituent classes based on existing data, current federal and state objectives and standards, professional judgment, and comments received from public scoping. Next, the list of constituents was narrowed down based on available data or detections in the historical monitoring information to about 60. Then, depending on the modeling tools and available data, either a qualitative or quantitative assessment was done for both with and without the project.

For water quality, the first step is the screening analysis, which identifies the constituents of concern that warrant detailed analysis. A list was developed with more than 438 water quality constituent classes based on existing data, current federal and state objectives and standards, professional judgment, and comments received from public scoping. Next, the list of constituents was narrowed down based on available data or detections in the historical monitoring information to about 60. Then, depending on the modeling tools and available data, either a qualitative or quantitative assessment was done for both with and without the project.

The slide on the lower left shows some of the constituents for which qualitative analyses are being done. Since there generally aren’t models for these constituents available, the analysis considers the sources of those constituents to the surface water or Delta waters, their concentrations, and how the project could potentially change those sources or concentrations.

The slide on the upper right lists some of the water quality constituents that have quantitative assessments based on model estimates.

“DSM 2 also provides assessments of locations of different source water fractions,” said Mr. Singh. “So for a given location, we can see how much Sacramento River water, seawater, or San Joaquin water is there. Based on those known concentrations, we can use a mass balance to calculate the concentrations of these constituents. In addition, we also used some available regression equations that relate EC to bromide and chloride for Western Delta locations to calculate concentrations.”

Socioeconomic analysis

Dr. Stephen Hatchett, Senior Principal Economist at ERA Economics, discussed the socioeconomic analysis.

Dr. Stephen Hatchett, Senior Principal Economist at ERA Economics, discussed the socioeconomic analysis.

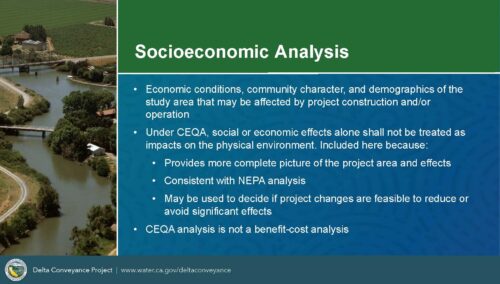

Under CEQA, social or economic effects aren’t generally treated as impacts on the physical environment, but they are included in the analysis because of significant public interest and a more complete picture of the project area and possible effects. There is a companion NEPA analysis, the federal environmental impact document, which does have more socioeconomic requirements. This information may be used to make decisions about whether mitigations or avoidance of effects are feasible.

Dr. Hatchett also pointed out that the CEQA analysis is not a comprehensive benefit-cost analysis. “You will certainly see things in it that relate to benefits or costs, but there’s no formal compilation and quantification in a way that some people might expect,” he said.

There were three basic rules for their methods and approach:

- The first is to find the best and most recent data to base the description of existing conditions and assessment of potential changes.

- The second is to be consistent with the other analyses in the EIR for other resources, including the agricultural resources and recreation chapters.

- The third is to use widely accepted and understood methods for the analysis and do it quantitatively where appropriate and applicable.

Dr. Hatchett then gave some examples.

The construction and operation of the project itself is the largest one quantitatively, so they have gathered estimates by year from the Project Design Team on the employment during project construction and operation. However, the project footprint will affect existing land uses most significantly agricultural land use, so the effects of that need to be considered as well. So everything is incorporated into an input-output regional economic impact model that determines the direct effects as well as the indirect and induced effects.

Agricultural production is linked to the GIS and land use analysis in other parts of the EIR. It was used to identify acres of crops that would be taken out of production due to the project footprint and gathered the most recent data on the production value. They then put that into the model to assess the larger effects of taking that land out of production. In addition, other basic information is presented that describes the agricultural economy in the area from the best available sources. Dr. Hatchett noted that all dollar-related estimates are indexed to a common point in time.

Other effects are incorporated into the socioeconomics section, including quantitative assessments of changes in population and housing demand, and qualitative assessments of community character, recreation effects, and local fiscal conditions. The chapter also includes descriptive text about the effects for the areas receiving the exported water.

Environmental justice

Carrie Buckman then gave an overview of how environmental justice is incorporated into the CEQA process.

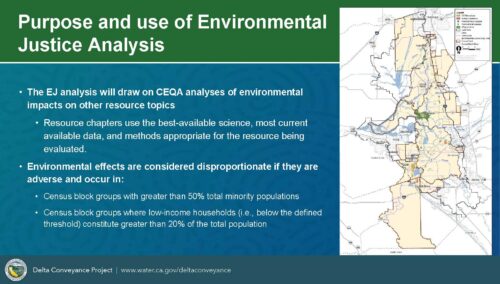

She began by noting that, in general, CEQA does not require an analysis of environmental justice. “We have to look under the CEQA process at potential significant environmental impacts, but economic or social changes, including environmental justice, are not in and of themselves a significant impact to the environment, according to CEQA.”

However, multiple state policies instruct state agencies to consider the impacts of their actions on environmental justice communities, defined as census blocks with greater than 50% total minority population or where low-income households constitute greater than 20% of the population.

“So the way that we’re looking at this analysis is if an impact is less than significant or has no effect, as a conclusion, we don’t carry that forward into the environmental justice analysis. But where an impact is potentially significant, we consider that in the environmental justice analysis to determine if it could have a disproportionately high and adverse impact on an environmental justice population. So we look at both the significant impact that’s identified and the mitigation measure because we want to make sure that mitigation measures are applied appropriately, and don’t in and of themselves, disproportionately affect an environmental justice population.”

“So the way that we’re looking at this analysis is if an impact is less than significant or has no effect, as a conclusion, we don’t carry that forward into the environmental justice analysis. But where an impact is potentially significant, we consider that in the environmental justice analysis to determine if it could have a disproportionately high and adverse impact on an environmental justice population. So we look at both the significant impact that’s identified and the mitigation measure because we want to make sure that mitigation measures are applied appropriately, and don’t in and of themselves, disproportionately affect an environmental justice population.”

Ms. Buckman also noted that they are working on a robust community benefits program as part of the proposed project; however, that program is not considered environmental mitigation or mitigation for environmental justice impacts.

Dr. Juliana Birkhoff, managing facilitator at Ag Innovations, then discussed the survey and outreach efforts.

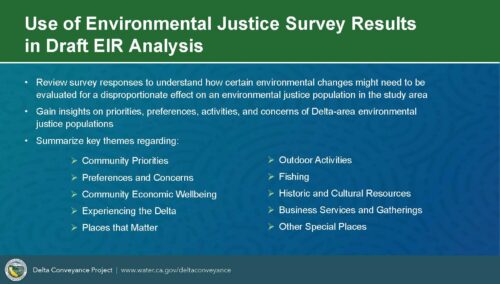

Ag Innovations has been working with DWR on outreach to environmental justice and disadvantaged communities for the Delta Conveyance Project. One of the first tasks was to conduct a survey in the fall of 2020 to find out from people how they work, live, recreate, and experience the Delta. They reached out in particular to the historically burdened, underrepresented people of color and the disadvantaged communities in the Delta.

Ag Innovations has been working with DWR on outreach to environmental justice and disadvantaged communities for the Delta Conveyance Project. One of the first tasks was to conduct a survey in the fall of 2020 to find out from people how they work, live, recreate, and experience the Delta. They reached out in particular to the historically burdened, underrepresented people of color and the disadvantaged communities in the Delta.

The survey also served to make sure people knew about the Delta Conveyance Project; a secondary objective was to see if they could increase the number of disadvantaged community members interested in participating in public engagement activities.

From the survey responses, they derived the priorities, preferences, activities, and concerns of the respondents. Then, they summarized the key themes into community priorities, preferences, economic well-being, and how folks experienced the Delta. The survey also included a map where people could mark their special places and say why it was special.

From that, they began outreach to disadvantaged communities.

From that, they began outreach to disadvantaged communities.

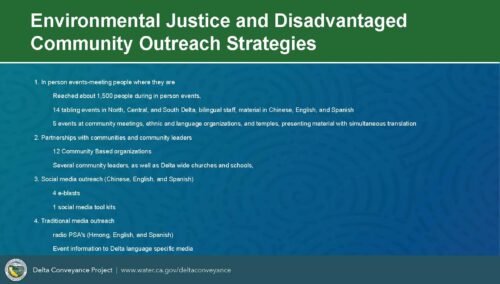

“Our goals for the outreach have been that people will know about and understand what the proposed Delta conveyance project is and its timeline,” said Dr. Birkhoff. “It’s an important project that’s had different iterations, so we wanted people to know what this current project does. We wanted them to understand how or if this project will affect or not their priorities and interests, and to understand how or why it’s worth their time and effort to participate. And then are they prepared to actually participate in the project’s public input processes?”

They worked on ‘meeting people where they are at,’ such as farmers’ markets, food pantries, school activities, church coffee hours, and festivals. They also partnered with community-based organizations, which helped them with meetings, social media, and languages. They also used traditional media, such as public service announcements, to reach people who were subsistence fishermen in the Delta. And they ensured they had translators available at events and that all materials were translated moving forward.

Considerations for the review process

The draft environmental documents are expected to be released mid-summer for a 90-day public review. The Army Corps of Engineers is developing a separate draft environmental impact statement under the NEPA process that will be ready likely shortly after the draft EIR for a shorter review period. Ms. Buckman said the review periods will overlap but will not be identical.

The Army Corps’ draft EIS will have similar information to the draft EIR, but there are differences. The Corps has some requirements for brevity, so the EIS will be shorter and will summarize and refer to the EIR in some areas. NEPA has different ways to determine the importance of impacts; they do not have the same types of significant findings as an EIR.

The baseline for the impact analysis is also different. With CEQA, the proposed project and alternatives are compared to existing conditions at the time of the Notice of Preparation. Under NEPA, they will compare the conditions with the proposed project or alternatives to the future no-action alternative. So it’s a different timeline for the impact analysis.

As for things to look for in the review, Ms. Buckman said that typically, people look at the project description to determine if the project is described well enough so that folks understand the project and can identify the potential environmental effects. The environmental setting must also be adequately described based on available information. The impacts include direct, indirect, growth-inducing, and cumulative impacts and should be evaluated in light of what is reasonably foreseeable.

Are feasible alternatives evaluated that meet project objectives and would avoid or reduce potential significant impacts of the proposed project? Mitigation measures should be included that would avoid, minimize or compensate for potentially significant impacts.

Are feasible alternatives evaluated that meet project objectives and would avoid or reduce potential significant impacts of the proposed project? Mitigation measures should be included that would avoid, minimize or compensate for potentially significant impacts.

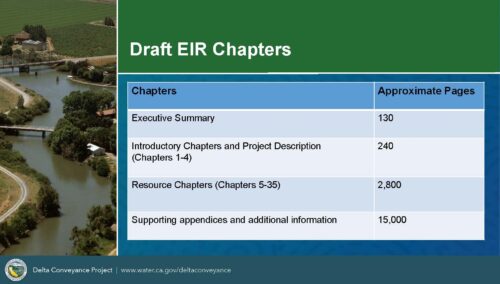

As for the size of the document, the executive summary is about 130 pages, the introductory material is about 240 pages, and the resource chapters are about 2800 pages. The supporting appendices and additional information are about 15,000 pages, but much of that material is modeling output included for reference.

Q&A HIGHLIGHTS

QUESTION: Chair Steven Brandt noted that the DISB has asked for chapter summaries in earlier comments. Is the 130-page Executive Summary going to include chapter summaries?

Carrie Buckman replied that they do not have individual chapter summaries, but they have compiled some summaries that hopefully will be helpful. One is that the executive summary includes a table that summarizes all of the impacts throughout the entire document.

They are also developing a summary for the general public that will provide information about the project and key pieces of information. “One of the things we’ve heard about CEQA documents, in general, is that they’re not always conducive to public understanding. It’s pretty complex legal document. So this other external summary will summarize the proposed project and the alternatives. It looks at key resources and some of the important findings and trade-offs in a way that isn’t intended to be comprehensive but will hopefully highlight some of the things that are of the most interest and the most important for people to understand.

QUESTION: Dr. Thomas Holzer questioned the planning horizon for the report as the year 2040 – that’s only 18 years away. The sea-level rise for that period was estimated to be 1.8 feet, but most projections show the sea level accelerating as you go through the century. So how is the project considering the longer-term future?

Amardeep Singh acknowledged the information he presented was mostly about 2040 because that is the quantitative modeling that has been done. The EIR will discuss the future at 2070, looking at the projected climate changes, how they expect the project to be operated, and the impact on the project under those conditions.

“The main thing is that the further we go out, there is a lot of uncertainty in terms of climate change assumptions, sea level rise assumptions, and what the regulatory environment would be,” he said. “There’s a lot of assumptions that we have to make, and doing quantitative modeling has some challenges associated with that. So there will be a qualitative discussion about climate change, looking at a period down the road, and what this project does under those conditions.”

QUESTION: Dr. Thomas Holzer asked, Who is the water supply reliability for? In other words, what are the metrics you’re using for the water supply reliability estimates?

“One of the metrics would be looking at the total project yield and how that yield is expected to change with climate change, hydrology, and sea level rise,” said Amardeep Singh. “One of the things we’re looking at is basically water supply for the State Water Project overall, and how it will change based on the existing conditions and moving forward with climate change and sea level rise, and whether we’re able to maintain that down the road … and how this project will be able to capture some excess flows that we can’t do right now to maintain that reliability.”

Dr. Holzer: What about reliable flows for the Delta itself?

“The project itself will operate to meet all the existing regulatory requirements, aquatics, and other resources that are important in the Delta as well,” said Amardeep Singh. “The analysis includes that –not the water supply, but just consideration in terms of different requirements and overall ecosystem, how this [project would meet that].”

Carrie Buckman added, “We are also looking at the different indicators that help us reflect on water quality and ecological parameters within the Delta. So we are presenting information in the EIR about flows at different locations and looking at changes as part of the impact analysis.”

QUESTION: Dr. Harindra Joseph Fernando asked why the Corps is involved? Is this the normal protocol?

Carrie Buckman replied that the Corps has to issue both a 404 permit for wetlands and a 408 permit for changes to the flood protection system, so they need to evaluate the project and perform a NEPA analysis before determining if they can issue permits.

“They’re not a project proponent; they’re not trying to implement this project,” she said. “They’re just evaluating it so that they can determine whether they should permit. So yes, it’s a very different perspective than DWR’s.”

“We are working on an environmental impact report under CEQA. And they’re working on an environmental impact statement under NEPA. So the requirements are similar, but not the same. It will be shorter. It has a little bit different focus. It does include some of the economic and environmental justice impacts that are not required under CEQA but are included under NEPA. So it will be a little different. But it’s a similar project and a similar process.”

QUESTION: Dr. Robert Naiman asked how the report treats floods. Does the report address the positive aspects of flooding? Ecologically flooding is probably one of the most important characteristics that you have in terms of shaping ecosystem processes. Does the report directly address how this project would impact the positive aspects of flood regimes?

Carrie Buckman said that for the purposes of the environmental review, they are looking at existing conditions and whether the project being considered has the potential to worsen those conditions. “One of our project objectives isn’t really to provide increased flooding for habitat. So I don’t think that we’re necessarily looking for that opportunity. We do have an analysis of how flooding will change. But I don’t know we are trying to capitalize on that opportunity because it is outside our project objectives.”

DWR Director Karla Nemeth noted that the state is working to reactivate floodplains for their ecological purpose, most notably in the Yolo Bypass. “The Yolo Bypass, which is outside of the legal Delta, has a reactivation of that floodplain for fishery purposes which certainly has downstream ecological benefit. That’s really important. So, as we think about this project and how this project would operate, we definitely want to preserve the positive effects of floodplain restoration projects that will be coming online over the course of the next 10 to 15 years.”

Dr. Lenny Grimaldo said that when he thinks of flooding, he thinks of all the available habitat that becomes accessible, not just on the floodplains but in tidal marshes as well. “We get activation of low salinity help with habitat that promotes species spawning downstream in the Delta and our project area. So for me, I think of all the portfolio of actions that occur with flooding and what we’re doing to promote those things. And these things are connected because we have to get fish off the floodplains and into the tidal marshes as they move to the ocean. So to me, I think it’s, it’s about connecting that bridge concept from upstream to downstream with the flooding concept.”