Panel discusses temporary urgency change petitions, transfers, and drought litigation

As California enters the second year of dry conditions, many water purveyors face minimal water supplies and have activated their drought contingency plans. So what more can an agency or district do besides water restrictions, conservation incentives, and other actions to reduce water demand?

At the spring conference of the Association of California Water Agencies, a panel discussed how temporary urgency change petitions, transfers, and litigation are sometimes used to respond to drought conditions. Seated on the panel:

- Erik Ekdahl, Deputy Director of the Division of Water Rights at the State Water Resources Control Board

- Don Seymour, Water Resources Manager for Sonoma County Water Agency

- John Rubin, General Counsel and Assistant General Manager of Westlands Water District

- Valerie Kincaid, a partner at the law firm of Paris Kincaid Wasiewski.

- Moderator Elizabeth Leeper, Senior Deputy General Counsel for the Eldorado Irrigation District.

State Water Board actions to address drought

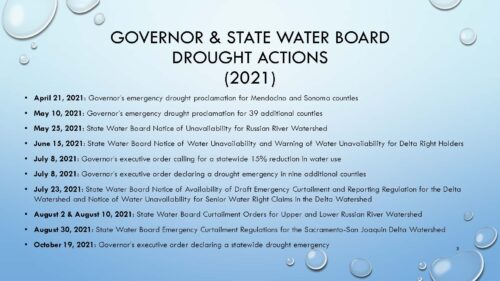

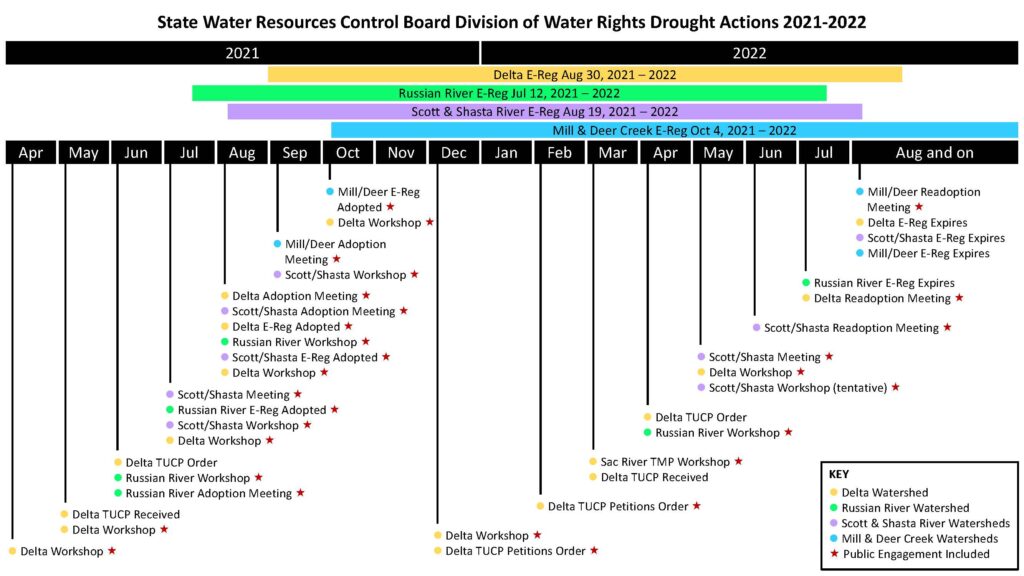

The Governor and the State Water Board have undertaken numerous executive and regulatory actions in response to the drought. Erik Ekdahl began by highlighting the key actions and sequence of events that led up to the curtailment and related activities of the Board over the last two years.

On April 21, 2021, Governor Newsom issued an emergency drought proclamation for Mendocino and Sonoma counties. Mr. Ekdahl pointed out that even though board staff was collaborating with stakeholders in some watersheds, the process didn’t start from a legal standpoint until the proclamation was issued.

Over the next several months, additional sets of proclamations expanded the drought beyond the Russian River Watershed to include the Klamath, the Delta watershed, and eventually the entire state of California.

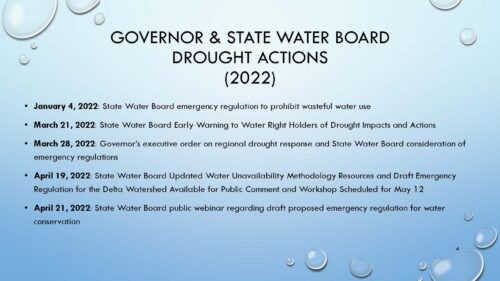

Activities to address the continuing drought have continued in 2022, with more activities expected over the coming months, including the readoption of emergency regulations.

“We went out of our way numerous times above and beyond what is called for in statute or regulations to solicit stakeholder feedback, to engage with the public, and really develop feedback on our processes, the methodologies that we used, and the draft and text of the emergency regulations that we ended up adopting,” said Mr. Ekdahl.

Temporary Urgency Change Petitions

One tool for water rights holders to manage scarce water supplies during drought is temporary urgency change petitions. Don Seymour briefly discussed how Sonoma Water uses the petitions to manage their Russian River supplies.

Sonoma Water is a wholesale water agency that provides water to customers, cities, and districts in Sonoma and Marin County. The primary source of water is the Russian River system. They co-manage Lake Mendocino and Lake Sonoma with the Army Corps of Engineers. Sonoma Water holds four appropriative water right permits with a face value of 75,000 acre-feet which authorizes Sonoma Water to directly divert and redivert stored water out of the two reservoirs. Amendments to those permits were last issued in 1986 with decision 1610.

“Almost 40 years later, just like a lot of watersheds, a lot of changes have occurred, which make a number of the terms and conditions in our permits, particularly how minimum stream flow requirements are determined and what those minimum flow requirements are, are really not reflective of the watershed or fisheries needs that are occurring now,” said Mr. Seymour.

Two changes, in particular, are drivers that, along with drought, make it challenging to manage the system.

The first is the Potter Valley Project, a small hydroelectric project owned and operated by PGE that was built over a hundred years ago. Historically, it has imported about 160,000 acre-feet of water annually into the Russian River system. The water is conveyed from the Eel River through a system of tunnels, penstocks, and conduits which is ultimately released into a powerhouse and then into the East Branch Russian River, about 12 miles upstream of Lake Mendocino. The project’s hydroelectric license is up for renewal, and its fate is uncertain.

“Since that water has been transferred, hundreds of appropriative water rights have been issued on the Russian River based on the availability of that water,” said Mr. Seymour. “In addition, the flood control manual for Lake Mendocino was developed with that water coming into the system. So with these changes, it’s become very challenging keeping the Russian River and Lake Mendocino reliable.”

The other significant change was in 2008, NMFS issued a biological opinion for the Russian River. Under certain year types, the flows during the summer are elevated and too high, so Sonoma Water is required to reduce those flows to improve the habitat for juvenile steelhead and salmon that are rearing in the mainstem of the river and Dry Creek.

“We’re required to make changes to reduce those flows,” he said. “The biological opinion does recognize it’s going to take time; that’s a complicated process. So in the interim, we have to file temporary urgency change petitions when under certain minimum streamflow requirements.”

Sonoma Water is pursuing permit changes to better reflect the current conditions, but it’s complex, and the CEQA issues are challenging. The process will take a few more years, so they will continue using temporary urgency change petitions to manage the system in the interim.

Since 2007, Sonoma Water has filed 16 temporary change petitions, four of those in just the last two years.

“We’ve been essentially operating under urgency change orders for the last two years,” said Mr. Seymour, noting that they will be filing for another one in May. “We’ve been filing both on under a number of categorical and statutory exemptions. It’s been very effective. We’ve received orders approving these petitions, and we have been successful in managing the system with them.”

“We’ve been essentially operating under urgency change orders for the last two years,” said Mr. Seymour, noting that they will be filing for another one in May. “We’ve been filing both on under a number of categorical and statutory exemptions. It’s been very effective. We’ve received orders approving these petitions, and we have been successful in managing the system with them.”

However, they come at a very high cost. The criteria in the box on the left are what applicants have to demonstrate that they have met. So the application requires detailed analyses and supporting documentation, which in turn requires staff time as well as complex hydrologic models and the folks that know how to use them.

The filing fees are calculated based on the face value of the permits being changed, which equates to over $60,000 each time they file. And the permit comes with rather burdensome terms and conditions to protect other users and the environment, such as complex fisheries and water quality monitoring and reporting.

“All in all, when Sonoma Water files these petitions, it costs in excess of $250,000 each, so it’s significant real money and shifting of staff time over to do this,” said Mr. Seymour.

The conditions in the permits restricted diversions out of the Russian River by 20%, which significantly impacted their retail customers and required significant weekly coordination to ensure the diversion reduction was met. It was an unanticipated change in Sonoma Water’s revenues that was not anticipated and built into the budget.

Lastly, Mr. Seymour acknowledged that temporary urgency change petitions aren’t a silver bullet. “You can only do so much with the temporary urgency change petition. Really what it does, at least for Sonoma Water, is allowed us to dial down minimum streamflow requirements. Last year, even with the changes we requested, we were forecasting Lake Mendocino could drain by early December if conditions had remained dry.”

“In the emergency regulation for the Russian River that was issued last July, it contained storage thresholds that if it dropped below, the State Board would take action,” he continued. “We dropped well below those storage thresholds. In August, the State Board issued unprecedented curtailments to the upper Russian River; over 1500 riparian claims and appropriative rights were curtailed. Even then, we were still extremely concerned with storage levels at Lake Mendocino. Really what stabilized the system was that huge atmospheric event that occurred in late October. So the temporary urgency change petition is a tool, but when you’re in severe conditions, it’s not even the tool that can maybe save the day.”

Next, Jon Rubin discussed how the State Water Project and Central Valley Project utilize temporary urgency change petitions.

Temporary urgency change petitions are an important tool for the Bureau of Reclamation and the Department of Water Resources for their operation in the Central Valley Project and State Water Project. Mr. Rubin said that the CVP and SWP have terms and conditions in their water rights that require them to operate to meet certain water quality objectives in the Bay-Delta. During dry periods, it significantly challenges the ability of the two projects to operate to meet those requirements, so the two projects have looked to temporary urgency change petitions to provide relief to allow the projects to best meet the purposes for the Central Valley Project and the State Water Project.

The Bureau of Reclamation and Department of Water Resources’ ability to use temporary urgency change petitions is subject to the governor suspending a provision of the water code, he noted. “The State Water Board has taken the position that water code section 13247 needs to be suspended prior to the Bureau of Reclamation and Department of Water Resources obtaining relief under their water rights for the requirements that concern implementation of the Water Quality Control Plan. Section 13247 of the water code generally requires state agencies to operate to meet water quality requirements. And so last year and again this year, the Governor’s Executive Order suspends 13247 of the water code.”

The Bureau of Reclamation and Department of Water Resources’ ability to use temporary urgency change petitions is subject to the governor suspending a provision of the water code, he noted. “The State Water Board has taken the position that water code section 13247 needs to be suspended prior to the Bureau of Reclamation and Department of Water Resources obtaining relief under their water rights for the requirements that concern implementation of the Water Quality Control Plan. Section 13247 of the water code generally requires state agencies to operate to meet water quality requirements. And so last year and again this year, the Governor’s Executive Order suspends 13247 of the water code.”

Temporary urgency change petitions were first used in 2009; prior to that, the projects did not require temporary urgency change petitions during times of significant drought.

“My sense is the need arose because of significant increases in the demand for water from the Central Valley Project and the State Water Project,” said Mr. Rubin. “The water quality objectives that the Bureau of Reclamation and Department of Water Resources are required to operate to were adopted in 1995. Principally, responsibility was placed on those projects through an order issued in 2000. But circumstances since 2000 changed significantly, and by 2009, the Central Valley Project and State Water Project were required to reoperate for additional environmental requirements that cost the Central Valley Project and State Water Project approximately 500,000 acre-feet on an annual average basis.”

“Because of those increased requirements and additional demands on the project, it makes it much more difficult for the projects to operate during drought to meet the water quality requirements in their water rights. So temporary urgency change petitions have thus become a tool to manage through droughts for the project purposes.”

Water transfers

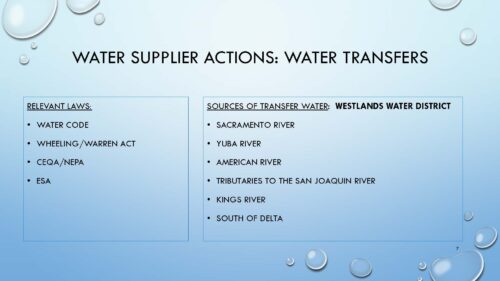

Another tool for managing through drought is water transfers. Jon Rubin then discussed how Westlands Water District utilizes water transfers.

Another tool for managing through drought is water transfers. Jon Rubin then discussed how Westlands Water District utilizes water transfers.

Westlands Water District has a contract with the Central Valley Project for up to approximately 1.2 million acre-feet of water from the Central Valley Project. Last year, the district received no water under its contract from the Central Valley Project. The same circumstance exists this year; the district will not receive any water again from its contract.

“The District supply over the last 30 or so years has been significantly and adversely affected by how environmental laws have been implemented,” Mr. Rubin said. “The District anticipates significantly less than the approximate 1.2 million acre-feet on an annual average basis. Because of that, the district relies significantly on transfers as a source of supply to mitigate those impacts.”

The district has developed strong partnerships throughout the Bay-Delta watershed and has acquired water from entities in the Sacramento Valley, Yuba River, American River, tributaries on the San Joaquin River, Kings River, and areas south of the Delta.

“The quantities of water vary based upon the surplus that exists within the areas that sell water, but the quantity of water that the district has been able to purchase can exceed 200,000 acre-feet in one year,” he said. “This provides some relief for the reduced supply given the contract quantity and the demands that we have. It mitigates in part the impacts of water shortages.”

Mr. Rubin noted that the water released for transfer to Westlands often provides instream habitat in the rivers and streams or improves cold water for fish below the dams.

The process has become less burdensome over the years since Westlands has had a transfer program. However, one significant task for many transfers is working through provisions in the water code. Three principles guide transfers:

-

- The first is to avoid injury to other legal users of water. When a transfer is proposed, changes in the water rights are necessary for the entity selling water to Westlands. One of the first considerations is whether the changes that are being proposed to sell water to Westlands would cause injury to other legal users of water. This provision applies to both temporary one-year transfers as well as longer-term transfers. The water code provision’s no injury provisions apply to the water rights that the State Water Board issues, as well as those water rights that are outside of the Board’s process.

- There must be no unreasonable impact on fish and wildlife. This principle applies to both the shorter-term urgency type changes that are required as well as long-term transfers. The no unreasonable impact to fish and wildlife is a balancing that the state water board undertakes, looking at the effect it has on the environment against the benefits of the transfer. This is separate and distinct from the requirements that may apply for environmental analysis under the California Environmental Quality Act.

- The third component applies when moving transfer water through a third party’s facilities, known as ‘wheeling’ water. One of the provisions under Water Code Section 1810 is to ensure that using that entity’s facilities will not unreasonably affect the overall economy in the area where the water is being sold from and moved to.

- The first is to avoid injury to other legal users of water. When a transfer is proposed, changes in the water rights are necessary for the entity selling water to Westlands. One of the first considerations is whether the changes that are being proposed to sell water to Westlands would cause injury to other legal users of water. This provision applies to both temporary one-year transfers as well as longer-term transfers. The water code provision’s no injury provisions apply to the water rights that the State Water Board issues, as well as those water rights that are outside of the Board’s process.

The California Environmental Quality Act can be required. There is a CEQA exemption under the water code for one-year transfers, but for longer-term transfers, CEQA applies. Westlands is often moving water through federal facilities and given their role as a contractor with the Bureau of Reclamation, there’s a need to comply with a National Environmental Policy Act as well.

Because of their federal nexus, Westlands must often ensure compliance with the endangered Species Act. One of the significant practical implications of that is through the biological opinion that controls the operation of the Central Valley Project.

“The window to move water is narrow,” said Mr. Rubin. “We are able to move water from north of the Delta to south of the Delta during the July through November period. That may sound like a long period of time to move water. But given that we’re looking to move transfer water using the Central Valley Project and State Water Project facilities, those facilities are operated, as you would expect, to move water for those projects first. So oftentimes, that window is limited. And with that limited window, the quantity of water that we may be able to move is also limited.”

Litigation

Next, Valerie Kincaid discussed litigation, noting that it is a reactionary tool, not a proactive tool. “It’s really asking people to stop their actions rather than having a proactive TUCP and kind of controlling your own destiny or doing transfers trying to get water. So when we’re talking about litigation, we’re really saying we’ve hit a pinch point where things need to stop. So the limitation of the litigation tool is that you’re not trying to drive the program proactively.”

Next, Valerie Kincaid discussed litigation, noting that it is a reactionary tool, not a proactive tool. “It’s really asking people to stop their actions rather than having a proactive TUCP and kind of controlling your own destiny or doing transfers trying to get water. So when we’re talking about litigation, we’re really saying we’ve hit a pinch point where things need to stop. So the limitation of the litigation tool is that you’re not trying to drive the program proactively.”

Ms. Kincaid noted that the litigation is always driven by the initial curtailment action of the State Water Board to which the litigants are responding. She discussed four pieces of litigation, two from 2014 and two coming out of the 2021 drought. These examples will highlight how different curtailment actions are and how different the litigation stemming from those curtailment actions is as well.

2014-2015 litigation

In 2014, the State Water Board adopted a curtailment order for Mill and Deer Creek based on meeting minimum fish flows. The tool of implementation for that was an unreasonable use determination.

“The fish flows were implemented through unreasonable use; it goes to the courts, and the courts said that the State Water Board can look at a fishery need, and they can say, in this specific Deer Creek instance, that keeping less than 50 CFS at a specific point is unreasonable because fish need that,” said Ms. Kincaid. “What has now become kind of a famous quote out of the case is that that’s a ‘belly scraping amount’ of water for these fish. So that is very specific to the Deer Creek curtailment.”

Also, in 2014, the State Water Board issued curtailment orders in the Bay-Delta watershed; these curtailments were based on priority rather than fish flows. “The State Water Board was saying, ‘we’ve got to protect everyone that’s in a priority class; we have to make sure that water users aren’t stealing water from each other.’ So no fishery flows as the purpose, just maintaining water right priority,” she said. “The way they implemented that was to develop a methodology of supply and demand. So implementation is not based on unreasonable use but on adopting a methodology in which the state water board looks at supply and demand and determines when you have water available for your use.”

Those curtailment orders were challenged, and the Santa Clara County Court ruled that the State Water Board doesn’t have the jurisdiction to regulate pre-1914 water right holders. The court also ruled that the methodology that the Board adopted for the curtailments violated the due process of those water right holders; it was considered an adjudication through the methodology.

“The State Water Board took that up on appeal, but they only appealed the pre-1914 authority issue. That appeal is pending in the Sixth District Court of Appeal,” she said. “One of the arguments being made is can the court hear this? Is this an advisory opinion? Because if you’re not deciding both issues, then the curtailment gets set aside either way. So why are we taking one issue and not the other? It’s kind of a wonky legal component there, but interesting from a legal practitioner point of view.”

“So you can see by those two pieces of litigation that you have really narrow viewpoints on what the State Water Board can do based on their curtailment action. They did two very different things in these watersheds, and therefore the litigation was very different.”

2021 curtailments

After the 2014 litigation, the State Water Board reconsidered how it could issue curtailments. The 2014 litigation was based on the idea of trespass under water code 1052; you are guilty of trespass if you take water that doesn’t belong to you from a higher priority user. The court said the State Water Board couldn’t really do that, and certainly not against pre-1914 water rights holders.

So in 2021, the State Water Board used their emergency regulatory authority under water code 10585 and adopted a regulation first; and then from that regulation, they issued curtailment orders.

The regulation was based on protecting water right priority and a very similar methodology that they used in the 2014 cases. “So everyone sued,” said Ms. Kincaid. “Some people interestingly sued on the regulation first, then subsequently on the curtailment orders, because it was a two-step process this time. First, you do a reg; then you do the orders. Some people sued on the reg and the orders together; others sued on one, not the other. So now we have seven cases in five different jurisdictions. We’re all going through a fairly messy venue argument right now about where this case should be; someone moved for coordination through the Judicial Council. So we’re all waiting.”

Ms. Kincaid noted that’s what happened in the 2014 cases; they were all put together in a coordination proceeding. “So we’re headed towards the same direction based on similar but somewhat changed methodologies … So we’ll see if the shifting approach is more lawful or not at all lawful.”

The other 2021 curtailment litigation piece is from the Shasta watershed. The Shasta curtailments had fishery flows and included groundwater too. The litigants in that moved for a temporary restraining order and received it.

Conclusions

Coming out of all of this litigation, there are snippets of where the State Water Board can go and can’t go, but we don’t have an overall picture of how to move forward in the next drought.

“Certainly, as a person who represents folks [in these proceedings], I’m not terribly interested in continuing to spend money fighting the State Water Board on every new curtailment manifestation,” Ms. Kincaid said. “We probably all need to take a step back and look at how we’re doing things potentially in non-drought years and come up with a plan where we can, at least from the Bay-Delta perspective, talk about priority when we’re not jostling in line. … I think we should probably talk about that line a little bit in terms of who has priority and who doesn’t. If certain people need to take cuts in certain years, what does that mean in other years? Does it cost money, or does it not? There are so many questions that we could resolve in a non-drought year.”

“So my plug is that litigation is necessary. It’s interesting. It can be very fast-moving. But it is a little bit of a stick that’s beating someone off. And I suggest that we all pull it back and in non-drought years figure this thing out from a holistic perspective, which litigation, unfortunately, does not give you.”

Jon Rubin noted that Ms. Kincaid represents entities that hold water rights and have concerns that the actions in the Bay Delta impair their ability to exercise their water rights in a lawful way. “Westlands has a different perspective on this issue,” said Mr. Rubin. “The transfers that Westlands relies upon, a significant amount of that water is conveyed through natural watercourses through the Sacramento River to the Delta, for example. So if diversions occur when there’s an insufficient natural flow or abandoned flow in the system, there’s the risk that the water supply that Westlands farmers invested in significantly can be taken unlawfully. And so we participate in these proceedings. And we’re supportive of an action by the State Water Board to protect our transfer water.”

“In addition, water previously stored by the Central Valley Project that is being moved through the system for Project purposes – the same circumstance could exist with regard to the Central Valley Project water at times of insufficient natural flow to support water rights,” he continued. “If those water rights are not curtailed, Central Valley Project water can be diverted to the detriment of the Central Valley Project. And so for the protection of Central Valley Project water and the protection of transfer water, the district was concerned and engaged, supportive of an action by the State Water Board to protect those supplies.”

Mr. Seymour noted that curtailments in the Russian River watershed don’t occur very frequently, but in 2014, there were some curtailments. “However, last year, of those 1500 water rights that were curtailed, three of them were our permits, and one of them was for rediversion of stored water in Lake Mendocino,” he said. “But we didn’t look at it as a negative thing. Without those curtailments, Lake Mendocino would have drained; it would have threatened the water supply for over 60,000 people in the upper Russian River. So it’s a slightly different perspective based on the predicament the Russian River system was in. We were actually supportive of those curtailments.”

Erik Ekdahl pointed out that historically, the State Water Board hasn’t issued many curtailment orders; last year was the first year they issued them in earnest in most watersheds. One of the lessons learned from the 2014-15 drought was that the State Water Board needed to have improved data.

“We first have to have the demand and supply data, and we have faith in that data. However, in some watersheds, that user-reported data is off by 86%, to the tune of 15 million acre-feet or more by watershed. So we had to go through a process to clean that up, which takes three to six months. Then we have to send notice if we find that there is insufficient supply relative to demand. That notice is not a strict order to tell you to stop diverting; it’s our finding that we don’t think you have sufficient supply relative to demand. Then we would have to send enforcement staff out to that particular point of diversion. If, in fact, we did agree that there was insufficient supply relative to demand, we would have to then develop a formal enforcement action, draft that, send it out, wait a number of days for a response, then proceed through a formal kind of enforcement action that can take two to seven years. That’s for one water right. So that’s why we don’t historically do a lot of curtailments.”

QUESTIONS & ANSWERS

QUESTION: I’m asking a question on the federal side for the Sacramento River. So the Central Valley Project contractors should only have been cut 25%, but the water wasn’t in Shasta. So how do we address that moving forward when the water is not there and contracts and diversion agreements can’t be met? Because we were facing that potentially on the Feather River with Lake Oroville and meeting the diversion agreements for the Feather River districts.

“Obviously, it’s a significant challenge,” said Jon Rubin. “I think it probably raises a larger question or issue. And that is, how are we going to manage into the future with a system that’s not meeting the needs of California, whether you’re looking at it from an environmental standpoint, an agricultural standpoint, or an urban standpoint? I would like to think that at least part of the answer is investing in infrastructure. There are a lot of projects out there that can be implemented that will produce a supply that can serve multiple purposes. And I think that that’s part of the solution.”

“I think another part of the solution is making sure that we’re using water as efficiently as possible for all of the purposes. There are areas of the agricultural community and in Westlands that are using water as efficiently as any other place in the nation. There are areas on the urban side doing the same thing. I think we really have to ask ourselves, are all of the areas that are using water using it efficiently? I think the environment is one of those areas that we can look at to see if water is being used efficiently. Are there other ways we can meet the biological needs of the ecosystem?”

“So for me, it’s making sure that we are investing, that we capture and appropriate water for multiple purposes by investing in infrastructure, and implementing our laws using water as efficiently as possible.”

QUESTION: This morning, we heard some recommendations for real-time water diversion, monitoring, and reporting with the purpose of helping to implement the existing water rights priority system. On the panel here this afternoon, we’ve heard a CVP contractor talk about some of the needs for curtailment in order to protect storage water releases that are not natural flows that are available for taking by other water rights holders. And the need to protect water transfers, same kind of thing. We’ve heard a water right holder, the holder of federal rights on a system, talk about the benefits of curtailment to protect the water supply for 60,000 people in the Russian River watershed.

So is the suggestion that one could derive from the comments of the two panels and the issues they have addressed that maybe the water right system could work pretty well? Certainly, everybody has developed a reliance with the knowledge that there is a water right priority system, there are juniors and seniors, and juniors get cut when there’s not enough available for all. What do you all think about real-time monitoring and reporting being carried out over time so that folks who verify their rights if tested can establish their priority and the amount of water that can go to the person with the priority? Is that a good idea or a bad idea in reality?

“At Eldorado Irrigation District, we have diversion locations where we’re exercising multiple water rights at a single diversion,” said moderator Elizabeth Leeper. “Sometimes that’s a direct diversion. Sometimes it’s previously stored water that’s being rediverted. So we might be a good example of, does real-time monitoring give you sufficient information about the exercise of an individual right where it’s not one right moving through one location?”

“My perspective on that is that improved data is a great idea; real-time monitoring, great idea; but it’s not going to solve the entire problem,” said Ms. Kincaid. “If you have all that real-time data, you will understand what supply is, but the problem is that you have a priority system that no one agrees to. I’ll tell you from a fairly senior water right holder’s counsel, I look at curtailment as, I’m going into a concert, I’ve got a ticket, I’m fourth in line, I think I’m going to get in. Okay. But there are a whole bunch of people in front of me who I don’t think have a ticket. But they said they left their ticket at home; they’ve been claiming that ticket for a long time. So they get let in anyway, and I’m not happy about it. The people behind me, they’re clearly behind me. But they need to get in more than me this year because of public health and safety. I get it. I might even be willing to say go ahead. But when are you going to pay me back? Next time in line? or not at all? And those things are foundationally undecided. And we need to decide them, and data will not get you out of those issues.”

“We have a foundational legal argument problem, and we’ve got to get that straight,” she continued. “The only way I can see to do that is a non-drought period of serious engagement and settlement. … I get it. In critical years, public health and safety has to go in front of me. I’ll tell you right now, I think ag should wake up. Because public health and safety keeps cutting in front of us ag users, and we keep letting it happen. And we never say, can we get that ticket back? Or can I get some of my money back for that? So we have to have a plan. We have to insist on planning. We must. So data will get you there, but it won’t get you all the way.”

FINAL QUESTION: I think we’re all dealing with very challenging conditions. So where do we go from here? What are some of the methods that we can employ moving forward?

“I agree 100% with Valerie’s comments about data not being the silver bullet; it’s not going to magically solve everything,” said Erik Ekdahl. “At the same time, I think it’s also absolutely key to where California needs to go in the future. Seven of the last nine years have been drought years; we’re in our own millennial drought that Australia saw 20 years ago. And with climate change all pointing towards the concept that we’ll see more of these more frequently, we’re going to have to address the accounting and balance the books of supply and demand.”

“One of the best ways to do that is starting to aim us towards this idea of real-time telemetry,” he continued. “It’s not that tricky. People do it all the time already. But we must figure out how to do it in a useful and integrated way. Because I think it not only opens up tools for the state board in the regulatory or more scary context, but it opens up immense possibilities for those locally driven solutions.

“If we look at the future of drought management, it’s real-time telemetry, a better understanding of data, and tying that to the ability of local water users to help manage those own supplies,” Mr. Ekdahl continued. “We’re actively taking those steps. Now, in the Russian River, we have a voluntary drought water-sharing framework released publicly yesterday that, in many respects, functions as a Plan B to curtailment. In the Scott and Shasta watersheds, there are local cooperative solutions that now, I think in the Scott, cover almost 100% of the groundwater acreage in that watershed, so that’s an immense step forward. And that’s all driven at the local level. The data is what I think prevents that from being an option in other places. And that’s where there’s immense opportunity in the future.”

“From the perspective of a water manager, Sonoma Water is responsible for managing the rest of the river, making releases from the two reservoirs to meet minimum stream flow requirements to over 100 miles of river,” said Mr. Seymour. “In that 100 miles of river, there’s hundreds and hundreds of water rights diverters that divert under their own water right. It’s not coordinated with Sonoma Water; we have no idea when those diversions will occur. So I agree; real-time data could be helpful. There’s the challenge of creating the tools necessary to digest that information and turn it into something useful that you can use as operational. But I agree more data would be helpful.”

“In response to the recent data question, I think it’s critically important,” said Jon Rubin. “You can go on to a website today and see to the cubic foot per second how much water is being pumped by the Central Valley Project from its facilities in the Delta. You can go on to the website and see how much water is being delivered by the Bureau of Reclamation on a monthly basis.”

“For example, the Central Valley Project is regulated with its pumping limited by a flow in two rivers in the Delta: Old and Middle River,” he continued. “We don’t know how much water is being pumped out of those rivers for use in the Delta. There’s no reporting that’s useful for us to know that and, and so will you have this conflict between high regulation of the Central Valley Project, what appears to be precise regulation of the Central Valley Project with a significant unknown of the consumptive diversions that are occurring in the Delta. So I think additional data will not solve the problem, but it will provide us with a lot more information. And I think we’ll be able to make a lot better decisions in terms of how we’re managing the system.”

“When we’re talking about investments in California water, a term often used as beneficiary pays,” Mr. Rubin continued. “Westlands is a predominantly agricultural water district. And oftentimes, when we’re looking at investment in infrastructure, the ask is for the agricultural water districts to pay. And I think the agricultural water districts such as Westlands have frequently stepped up and invested when necessary to improve the supply for the farmers in Westlands. But I would hope that people appreciate, particularly after going through the last couple of years with the pandemic, that the benefit of agriculture in California extends well beyond the farmers. The farmers provide the food that we relied upon in our produce departments, and we need to recognize that when we’re looking at infrastructure investment.”