At the May 24th meeting of the State Water Resources Control Board, Delta Watermaster Michael George updated the board members on the changes to water use reporting schedules, the Delta Dry Year Response Pilot Program, the investigation into alleged unlawful diversions in the Delta, and curtailments in the Delta.

Water use reporting transitions

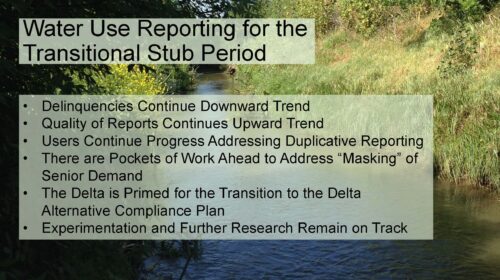

Michael George began by noting that the transition in reporting schedules has been challenging due to a change in schedule and a change in the reporting period. Nonetheless, it’s been going fairly well as delinquencies continue to decline. Currently, only five licenses and 40 statements out of 2500 are delinquent. He attributed it to effective outreach and the extraordinary support from reclamation districts, engineers, lawyers, and the Delta water agencies to help make sure that people file on time.

Michael George began by noting that the transition in reporting schedules has been challenging due to a change in schedule and a change in the reporting period. Nonetheless, it’s been going fairly well as delinquencies continue to decline. Currently, only five licenses and 40 statements out of 2500 are delinquent. He attributed it to effective outreach and the extraordinary support from reclamation districts, engineers, lawyers, and the Delta water agencies to help make sure that people file on time.

Secondly, more important than being on time is doing a good job, and the quality continues to improve. This is due to actions taken by the Board and the water community to improve the quality of the reporting. The problem of duplicative reporting, which happens when folks report the same water use under their licenses and their statements, has largely been eliminated.

There is an issue with what Mr. George called ‘masking’; this occurs when people report their water use under their license, but they move to their more senior water rights if their license gets curtailed. “In effect, reporting under the more junior right masks the more senior demand,” said Mr. George. “So when we need to curtail, we are playing a bit of a whack a mole game; [curtailing] the licenses, only to have the migration of water use move over to the statements.”

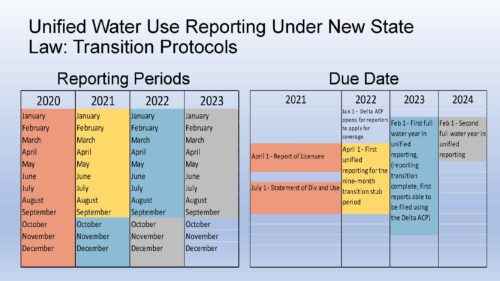

The Delta is now in the first year of the alternative compliance plan, which began with the new water year last October 1st and will end on September 30th, 2022. This is the first year the water use will be reported by water year rather than the calendar year.

“Most of it will be reported under the alternative compliance plan, which will give us more timely data developed on a consistent basis, that is machine-readable, and has a lot of data visualization to help people understand what’s going on in much closer to real-time in the Delta,” said Mr. George.

Work is continuing on refining the alternative compliance plan, he said. The Delta Measurement Experimentation Consortium is working on a new series of experiments and further research to improve the correlations between measured diversions and the ET from crops in the field.

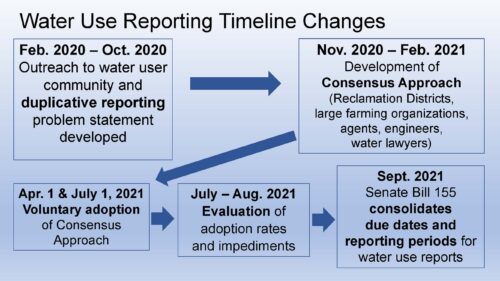

Mr. George then went into some detail on the changes with water reporting. The effort began with an extensive outreach period on duplicative reporting from February to October of 2020; a community problem statement and the consensus for it was developed among reclamation districts, large farming organizations, lawyers, engineers, and the Delta water agencies. Then, when those water use reports were filed in April and July of 2021 for the water year 2020, the voluntary efforts to eliminate duplicative reporting gave a much better sense of actual water use and under what level of priority.

Mr. George then went into some detail on the changes with water reporting. The effort began with an extensive outreach period on duplicative reporting from February to October of 2020; a community problem statement and the consensus for it was developed among reclamation districts, large farming organizations, lawyers, engineers, and the Delta water agencies. Then, when those water use reports were filed in April and July of 2021 for the water year 2020, the voluntary efforts to eliminate duplicative reporting gave a much better sense of actual water use and under what level of priority.

After the reports were submitted, they evaluated the adoption rate and determined that 65% of the reporters were using the method to avoid duplicative reporting. So they considered actions to increase that rate; what were the reasons for not adopting it, and how can that be overcome?

In addition, SB 155, a trailer bill, was passed, which consolidated the due dates for all reports to February 1st, rather than July, and all the water use reports to the water year. This means the information will be reported earlier and will be easier to correlate with Open ET and other data available for the same time period.

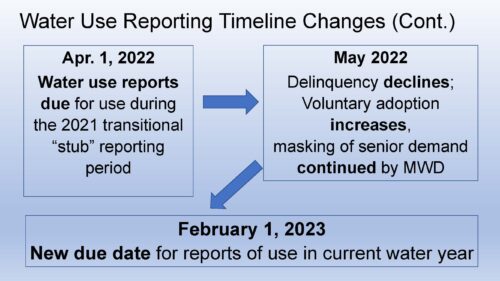

The most recent reports for both statements and licenses were due on April 1st. Next year, those reports will be due by February 1st, 2023, for the water year that ends on September 30th, 2022.

“The net benefit of this is better data achieved on a more consistent basis with a higher level of reliability and consistency so that we can use the data to make closer to real-time decisions,” said Mr. George.

Implementation of the Delta Dry-year Response Program

Mr. George then turned to a major effort in the Delta to respond to the drought conditions. Reservoir levels were low at the beginning of the year and continued dry conditions were predicted. So the Delta water agencies, the Department of Water Resources, the Delta Conservancy, the Delta Protection Commission, the Delta Stewardship Council, the State Water Board’s Division of Water Rights, and the Delta Watermaster’s office quickly pulled together a program for responding to continued dry conditions.

Mr. George then turned to a major effort in the Delta to respond to the drought conditions. Reservoir levels were low at the beginning of the year and continued dry conditions were predicted. So the Delta water agencies, the Department of Water Resources, the Delta Conservancy, the Delta Protection Commission, the Delta Stewardship Council, the State Water Board’s Division of Water Rights, and the Delta Watermaster’s office quickly pulled together a program for responding to continued dry conditions.

With $10 million in funding provided by the Department of Water Resources, they developed a pilot program to demonstrate what water conservation actions would work in the Delta and compare them to see if the same actions in different parts of the Delta will yield the same results. They received 85 applications for funding, of which 35 were approved. The fields are monitored, and evapotranspiration data is available through Open ET.

“So, for instance, a farmer joins the program and says, ‘I’ll forego a summer corn crop, and instead just leave my stubble from my winter wheat in the field, to protect from evaporation from bare soil, and to keep roots in the soil for the Healthy Soils program,” said Mr. George. “So we’ll take a field nearby, where another farmer, sometimes even the same farmer, is growing a corn crop. So we’ll be able to have a very good comparison.”

The studies will determine the effect of these actions on reducing water use and protecting water quality and help understand what can be done on a predictable basis in future dry years.

Additional funds are included in the Governor’s May revised budget, and assuming that comes through, they are planning to move from a pilot program to a program for the upcoming water year.

Investigation of alleged unlawful water diversion in the Delta

Mr. George then gave an update on the investigation of water exporter complaints alleging unlawful water diversion of the Delta. This complaint originated as a letter from the Friant Water Authority to Chair Esquivel, which then went to the Office of the Delta Watermaster to begin the investigation.

Mr. George then gave an update on the investigation of water exporter complaints alleging unlawful water diversion of the Delta. This complaint originated as a letter from the Friant Water Authority to Chair Esquivel, which then went to the Office of the Delta Watermaster to begin the investigation.

The Office of the Delta Watermaster and the Division of Water Rights worked together on the investigation recognizing the implications for impacts throughout the Delta watershed and the export communities served from the Delta.

The complainants were also brought into the investigation, working collaboratively and transparently to sort out the complaints, gain a common understanding of the issues, and a conclusion that would be credible with all parties. Friant Water Authority was soon joined by the State Water Contractors, San Luis Delta Mendota Water Authority, and Tehama Colusa Canal Authority in the complaint.

The complaint was based essentially on a mass balance analysis. The exporters looked at the inflows and the outflows from the Delta, with the difference between the two being depletions within the Delta. So the first step of the investigation was to refine the mass balance approach by determining how there could be more certainty about the inputs and disaggregating the pieces to understand what was going on.

They set up a technical subgroup, including people from the State Water Board, the water contractors, and engineers. They first challenged the complainants to refine their analysis, which they did; the Board staff then tried to replicate their analysis to see if they could come to the same conclusions using the same data sources. Then they dug into the discrepancies and worked to bring the range of certainty for each of the inputs to +/- 5%. They also looked at other areas where data could be improved and further refined the analysis.

“We didn’t always make it, but we generally got close,” said Mr. George. “But we also realized that we were dealing with so many variables that it was a compounding issue even if we got down to a +- 5% on each.”

As a result, they did come to some conclusions and are currently drafting a summary and report of those conclusions.

First, the current laws do not allow individual enforcement actions based on the data and the analysis that we have. “In other words, as a result of the gross water balance, there appears to be less natural flow coming into the Delta than there are riparian demands in the Delta,” he said. “Therefore, one might say, as the complainants did, it looks to us like there are unlawful diversions in the Delta; the difference of primarily riparian demands against reduced natural supply means that riparians take project water released from storage for different purposes. The available data and the requirements of the burden of proof don’t allow us to bring individual enforcement actions against individual riparian demands.”

During the investigation, they reduced the amount of actionable information they were using. For example, the northern part of the Delta has a backup supply in the form of a contract with the State Water Project. So they explained how the contract worked, but the net effect was to say that even if they found an unlawful diversion, it would only be changing the demand to the State Water Project.

They focused their attention primarily on the Central Delta, Southern Delta, and some of the agricultural areas of Contra Costa County. They also worked to understand how much water was at stake; if they successfully identified and stopped unlawful riparian diversions, what would be the effect? This helped to focus on where continued development of data was needed for wide reliability and begin using the new tool Open ET.

“One of the biggest things that came out of this was developing a common understanding of other avenues available for addressing the issues the complainants brought forward,” said Mr. George. “So that’s really where we’re going with the closing of this investigation without an enforcement action being taken, but with a lot more work to do to identify how to take action on the issues.”

Through the process, they discovered several unresolved legal issues. “Where we have differences of opinion, we disagree violently with each other, and we’re all convinced we’re absolutely right,” he said. “We can go to the legislature and ask the legislature to pass a law. We can go to the courts and ask the courts to determine what the law is when it comes to the water board. We can ask for regulations to resolve the conflict. Or we can negotiate or collaborate. But to negotiate and collaborate, which is faster, cheaper and both durable and flexible, it requires the kind of data that we are developing but don’t yet have.”

During the discussion period, Mr. George elaborated on perhaps the largest looming unresolved legal issue: the conflict between riparians and appropriators during times of shortage.

When California became a state, it adopted the common law; riparianism was part of that. Later, the priority system was overlaid on it. “We never resolved the fact that those two systems allocate shortage, not only differently, but on a basis that is inconsistent. So that is an example of a thorny, difficult, unresolved legal issue. The riparians are supposed to share the shortage correlatively; the [appropriators], first in time, first and right.”

In the Delta, there’s a conflict between the water rights of riparian users and early appropriators, sometimes even on the same watercourses. “You get into this circumstance where the appropriator says, ‘you can’t tell me, Mr. Watermaster, at what priority I should be cut off because you haven’t invoked the correlative reduction on the riparians.’ “I say, okay, let me go talk to the riparians. And they say, ‘you can’t determine what the correlative reduction is until we know where the appropriators are going to be cut off and, importantly, until you decide what water is available to a riparian now.”

There are some data issues and some tough legal issues. “Are the riparians in the Delta the intended beneficiaries of the project’s design and obligation to provide a freshwater pool from which to draw water? I’ve got lawyers who I respect on both sides of that issue. So maybe this is just one of those things that can only be settled by litigation. … But one of the problems with litigation in the Delta is that they’re often designed to be so fact-specific that their application to other fact circumstances is limited.”

“So what I’ve said to both sides is maybe the answer here is to develop a case that we can agree on and where the facts are stipulated. It would save a lot of time and money going through a discovery period to stipulate the facts that isolate the issue we want to resolve. However, it becomes very clear that there’s a risk to everybody in resolving those issues. You might not get all your claim; it might not be as clear as you’d like it to be. There might be conflicting and confounding information that you’re going to take and present to a tribunal that doesn’t have your deep background in water law. And you might get decisions that, let’s say, are oversimplified and not very useful.”

“So maybe we should do something else, like develop the information that we would put into that stipulated settlement. And then see if there might be areas where we could test for a while, instead of trying to enter into a permanent contract, maybe four or five years with some off-ramps, where we could try things together to see what the outcomes are. Those are the kinds of mechanisms for resolution.”

Curtailments in the Delta

Mr. George began by pointing out that drought in the Delta is experienced differently than in the rest of the Delta watershed; it is not a lack of physical water supply but rather a heightened risk to water quality. The Delta is a tidal estuary with important riverine influences, and it’s the freshwater flow that keeps the salty bay water from intruding into the Delta. So the Delta Dry Year Response Program focuses on creating a larger margin of reduced risk of salinity intrusion, as well as water conservation.

Mr. George began by pointing out that drought in the Delta is experienced differently than in the rest of the Delta watershed; it is not a lack of physical water supply but rather a heightened risk to water quality. The Delta is a tidal estuary with important riverine influences, and it’s the freshwater flow that keeps the salty bay water from intruding into the Delta. So the Delta Dry Year Response Program focuses on creating a larger margin of reduced risk of salinity intrusion, as well as water conservation.

“So keeping salt at bay, no pun intended, is probably the most important challenge in the Delta, not just for interior Delta water uses, but for all beneficial uses, whether for the ecological health of the estuary, for export, or for agricultural water uses,” he said.

The Division of Water Rights held a workshop in May to describe additional refinements to the water unavailability methodology. On the day of the meeting (May 24th), the only curtailments in the legal Delta were project curtailments for a few of the water rights and permits from the federal project. Term 91 was not in effect at the time, but later did go into effect in early June.

Nonetheless, they are planning and working with Delta water users on the assumption that the continuing persistent drought will require curtailments of licenses and likely some of the pre-14 water rights in the Delta. Unlike last year, where those curtailments only came for eleven days at the end of the irrigation season, it will be much deeper this year.

“The methodology today, much like our investigation, does not support riparian curtailments,” he said. “There are too many variables with too large of a compounded range of uncertainty to get to that.”

Mr. George noted the recent analysis by the Public Policy Institute of California, which presents a different way of looking at inflows, uses, and outflows in the Delta.

“One thing that really stood out to me is that over a number of years – dry years, wet years, recent years historic years, the depletion of water within the Delta is very steady at about 1.8 million acre-feet,” he said. “Given that fact, now we can take information that we’ve gleaned from the better water use data that we’re getting, from the new tool of Open ET, and from the investigation that we’ve just been through. And now we can look more carefully into how to disaggregate that 1.8 million acre-feet of use within the Delta to figure out what of it is subject to management.”

There are elements of water use in the Delta that cannot be managed in the same way as crops, such as evaporation from open water, riparian vegetation, and invasive aquatic vegetation.

“So as we get into that, we are going to continually narrow our focus on what we can manage, and how the information that we get allows us to adaptively manage in closer to real-time to make management adaptation changes in the Delta that will result in an outcome rather than a lot of finger-pointing.”

Collaboration on Integrated Responses to Wicked Challenges in the Delta

Mr. George acknowledged the many collaborative efforts underway in the Delta. One of those is the Delta Channel Maintenance Workgroup, which came together to find a solution to the channels in the South Delta, which have become clogged with sediment in recent years.

Mr. George acknowledged the many collaborative efforts underway in the Delta. One of those is the Delta Channel Maintenance Workgroup, which came together to find a solution to the channels in the South Delta, which have become clogged with sediment in recent years.

The Governor’s revised budget includes funds for dredging 10 miles of South Delta channels to increase channel capacity, reduce invasive weeds, and improve flood management. The dredging will recover the channels’ historic capacity, and the dredged materials will be used to support the surrounding levees.

“It is an action that came out of looking at the problem through many different lenses, getting people to understand that it was a shared problem that none of us could solve individually,” said Mr. George. “By making the problem bigger, you brought more people to the table with an interest in this. For instance, the two most important proponents of this are the State Water Contractors and the South Delta Water Agency.”

Mr. George noted that when the Board adopted the 2018 update to the Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan, it called for monitoring special studies in the South Delta. The effort has been broadened so it will inform comprehensive operations changes that could make a difference in the Delta.

Region 5, the Delta Watermaster’s Office, the South Delta water agency, Contra Costa Water District, and others are sharing their knowledge about the problems of salinity, channel throughput, and other issues to inform a master plan to improve conditions.

It’s important to empower regional responses. “The Delta, as I’ve said many times before, is not a monolith. It’s not one place. It’s different regions. There’s a good reason why there’s a North Delta Water Agency, a Central Delta Water Agency, and a South Delta Water Agency – because the problems, opportunities, and demands in those areas are different and need to be managed differently.”

“Nonetheless, it’s important to bring the Delta together for a unified voice and to look at how they can solve problems together and collaborate with people who want to solve some of those problems as well,” he continued. “So it’s outreach and dealing with the communities of interest, listening to them, understanding their needs. My experience is that you can say no, but only after you’ve listened to the problems. And that’s what we’re trying to do.”