The Delta is an intricate network of waterways, canals, and sloughs connecting the Sierra Nevada watershed with the San Francisco Bay. It is considered the hub of California’s water supply, supplying fresh water to two-thirds of the state’s population and millions of acres of farmland. It is also the largest freshwater tidal estuary on the west coast, providing important habitat for birds along the Pacific Flyway and the fish that live in or migrate through the Delta. However, increasing drought and sea level rise make it more challenging for water managers to meet the freshwater needs of all who rely on the Delta.

In May of 2022, the California Council on Science and Technology (CCST) brought together experts to discuss the issues related to managing salinity in the Delta, given the impacts of climate change. The briefing was in partnership with the Delta Stewardship Council’s Delta Science Program and the Office of Assemblymember Aguilar-Curry.

CEO Amber Mace began by noting that the CCST is a nonpartisan nonprofit created at the request of the legislature to bring science and technology advice from the wealth of academic and research institutions throughout California and beyond to inform policymakers at the state level in the legislature, the executive branch, and the governor’s office. The CCST works to bridge the gap between science and policy by listening to what policymakers need and figuring out how to translate the science into something actionable, useful, and relevant. They also work to create relationships between policymakers and the scientific experts in our network. They have several mechanisms for doing this work, including fellowships for Ph.D. scientists and engineers, holding briefings and workshops, and producing peer-reviewed reports. The Council’s Disaster Resilience Initiative focuses on how California can build resilience to the overlapping intersecting disasters that can occur. These disasters can be very disruptive, but at the same time, that disruption creates an opportunity to rethink how we do what we do and try to improve the system for everyone in California.

The moderator for the panel was Karen Kayfetz, an environmental program manager at the Delta Stewardship Council, who has had over a decade of experience working on science-based management of natural resources in the San Francisco Bay-Delta.

Ms. Kayfetz began by noting that the Delta is home to half a million people and 700 species of plants and animals. It’s important to all Californians because it’s the hub of several major water projects that collectively provide fresh water to two-thirds of Californians and a $50 billion agricultural industry that serves the entire country and depends on the Delta’s fresh water to thrive.

However, the Delta is also the largest estuary on the West Coast. An estuary is where freshwater and saltwater mix. The balance of freshwater flowing out from the Delta, salty water flowing in from the ocean, and runoff from agricultural lands affects the salinity levels of water within the Delta.

Water flows through the Delta are carefully controlled by water managers to meet regulated salinity levels. But climate change, including increasing drought and sea level rise, is expected to make meeting the fresh water needs of Delta end-users more challenging.

The panelists then introduced themselves:

The panelists then introduced themselves:

Dr. Jay Lund is a Professor of Civil Environmental Engineering at UC Davis who has been working on the Delta for about 20 years. His specialty is the operation of large and small water systems, particularly regional water systems, for which the Delta qualifies.

Dr. Brett Milligan is a Professor of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Design at UC Davis who works on multifunctional adaptation to climate change through the lens of landscape design and approaching that through re-envisioning what infrastructure is. “Basically, I’m taking the past social and ecological factors and making that foregrounded in how we design for that. And specific to this, I had a hand in a project called Franks Tract futures, which was a multi-benefit project in the Delta trying to attenuate salinity while also creating recreational and ecological benefits.”

Dr. Nigel Quinn is an earth scientist at the Berkeley National Lab, where he’s been for about 35 years. His work focuses on the watersheds draining into the Delta, specifically the San Joaquin, and agricultural and wetland drainage management. He has affiliations with UC Merced, UC Berkeley, and Fresno State, and he’s been a consultant with the Bureau of Reclamation for almost 40 years. Much of his work involves mathematical and water quality modeling of salinity, selenium, and other contaminants.

QUESTION: Why is it so important to maintain freshwater supplies in the Delta?

Dr. Nigel Quinn said that it’s important to preserve the ecosystem and the fish species that have adapted to the Delta’s hydrology. The Delta also supplies water to agriculture both in and south of the Delta, especially to the west side of the San Joaquin Valley and municipalities in Contra Costa County, the East Bay, and Southern California. In addition, industries that extract water from the Delta rely on consistent water quality.

“It serves a lot of people, but it’s also very fragile,” he said.

Dr. Jay Lund noted that most people in the Bay Area don’t realize that most of their water comes from the Delta, either directly from water pumped out of the Delta or indirectly from diversions upstream of the Delta for the Hetch Hetchy and Mokelumne Aqueduct systems.

Dr. Brett Milligan added that we developed a need to keep the Delta fresh. “There are many time questions of how the Delta used to be, what it is now, and what it might be in the future under radically different conditions,” he said. “So it’s somewhat of a time question, but we have come to depend on it in the way that it currently is.”

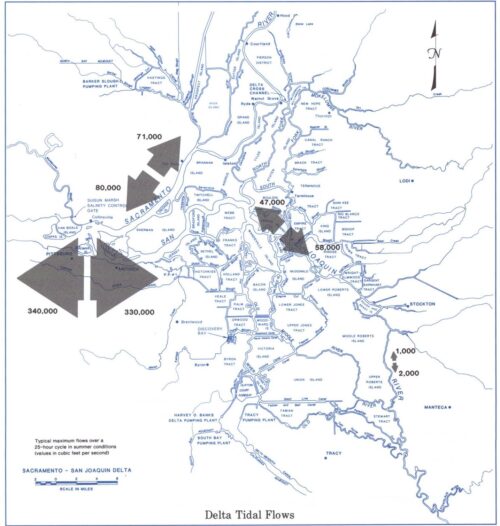

Salinity in the Delta is mostly from seawater diffusing inward with the tides, noted Dr. Lund. The tides flow in and out twice a day, and that influx and outflux of water from the Delta both bring salt water in and send freshwater and saltwater out.

“That mixing is the biggest source of salt in most of the Delta, particularly in the western parts,” Dr. Lund said. “That also means that different parts of the Delta tend to be more or less saline than others. So when we talk about salinity in the Delta, we’re primarily talking about the western Delta if things are going well, and sometimes the Central Delta if things are going poorly.”

Karen Kayfetz noted that time dependency is a product of how we manage and use the fresh water in the Delta. “The threat of salinity intrusion is based on, what is it threatening? What do we currently have in place that it is there to threaten? And what are the parts of infrastructure or the other human uses that we value now? And that’s a question of time and space.”

QUESTION: Where do the salts in the Delta water come from?

Most of the salt in the Delta comes from seawater that diffuses inwards, Dr. Lund said. Other sources are inflows into the Delta from nominally freshwater that contains some salt, including the San Joaquin River, which brings in salinity from agricultural drainage.

Most of the salt in the Delta comes from seawater that diffuses inwards, Dr. Lund said. Other sources are inflows into the Delta from nominally freshwater that contains some salt, including the San Joaquin River, which brings in salinity from agricultural drainage.

Agriculture on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley uses Delta water for irrigation; those supplies contain salt, so any drainage has salt. It returns to the San Joaquin River saltier than when applied as irrigation water, said Dr. Quinn. He noted that the state and federal wildlife refuges and private wetlands release their ponded water in the spring, which is a significant source of salt. And oil refineries and municipal discharges are also sources of salt in the Delta.

QUESTION: How does the switch from annual crops to perennial crops change the salinity of agricultural return? What about the reduction in snowpack – how would agricultural return change?

Dr. Quinn answered that in the past, there used to be a mix of crops, some of which could be fallowed to free up water for other agriculture and cities. For many years, in the Sacramento Valley, farmers have been paid not to farm and transfer that water to other agriculture and urban uses. However, nowadays, there is a significant amount of permanent nut and fruit orchards.

As water has become more scarce, farmers have invested in drip irrigation and other water-saving devices, which reduces the amount of water applied as well as the return flows.

“This has been happening on the western San Joaquin as water has become more scarce,” said Dr. Quinn. “Farmers on the west side very rarely get 100% contract water supply anymore, so there’s been an increasing amount of drip irrigation. But, of course, not every farm has drip irrigation. But there’s been a steady progression over time.”

Dr. Quinn noted that concentration is also a factor. “As farmers conserve more water, there’s less water to dilute this salt. So as farmers do a better job of conserving water, the quality of their return flows tends to degrade. So it’s salty water that comes off; there’s just less of it. So as the loads to the river reduce, the concentrations actually can go up.”

QUESTION: What are some of the available strategies for managing Delta salinity?

Dr. Jay Lund noted that there have been a few suggestions over the years. The first, considered in the 1920s, was to build a dam about where Benicia is now to keep saltwater out of the Delta. However, after an elaborate analysis for the time, it was decided that it was cheaper and more convenient to use Delta outflows to repel seawater. That is the strategy that continues today and is embodied in the current regulations.

“Primarily, what we do is we regulate Delta outflows, Delta inflows, and Delta pumping, the net of that being outflows to keep seawater out and to flush some of the salts that otherwise would accumulate in the Delta out to sea,” said Dr. Lund. “That strategy has been modified this year and last few years by adding an emergency salinity barrier, which means that it doesn’t take quite as much Delta outflow to keep the salts out of the Delta.”

QUESTION: Moderator Karen Kayfetz noted that Delta outflow comes from releases from upstream dams, so the reservoirs are managed in the summertime and especially during drought to keep the saltwater out of the Delta. The Delta salinity barrier is helping to retain water in the upstream reservoirs. What about the reservoir management aspect of this salinity problem?

Dr. Jay Lund agreed that the reservoirs are important for regulating Delta inflows that, combined with the regulation of pumping, o provide the outflows needed to keep salts out. He pointed out that before dam construction and irrigated agriculture in the Central Valley, groundwater and spring snowmelt provided enough outflow to keep salinity from encroaching too far into the Delta.

“So it’s not just the reservoir operations; it was mostly the upstream diversions that first caused salinity intrusion problems for the Delta,” Dr. Lund said. “In the 1930s, when agriculture had been well established throughout the Central Valley – that drought was the time when we had the most Delta salinity intrusion ever.”

Dr. Brett Milligan pointed out that the Delta has been radically altered. Historically, the Delta was a gigantic wetland sponge that would fill up with rain in the winter and slowly release that water in the drier months. “It was like the whole pace of water movement to the Delta was quite slow as it was quite absorptive and would hold it. Now the floodplains are completely separated from the channels, and the channels are wider and bigger, so it’s like an expressway of water through the Delta; it’s not held at all. It’s all very fast in terms of velocity of how it moves through there. If we still had those wetlands, you would not have to use as much water coming out of those reservoirs because you’re just pushing water through there all the time … So, it is a radically different condition than what it was in the past.”

Dr. Nigel Quinn noted that the placement of barriers isn’t a total win-win; it can affect some farmers trying to draw water to irrigate their fields because the water levels are too low.

One strategy has to be reimagining the whole Delta, Dr. Quinn added. “It needs to be thought of as a whole. We need to start thinking about the system in a different way. And until we do, we’re not going to solve a lot of these problems. Jay and I are both engineers, so we always think, ‘change the plumbing and change regulation.’ That’s typically our strategy. We’re not sociologists, but to my way of thinking, this is a social sciences problem as much as it is an engineering problem.”

QUESTION: Has there been consideration of a physical solution such as a control structure across the Carquinez Strait?

Dr. Jay Lund said that it was considered first in the early 1900s. The first California Water Plan in the 1930s considered the building of a dam by Benicia or the Carquinez Strait. Then there was the famous Reber plan in the 1950s that would have put a dam across the Golden Gate. As recently as 1978, he saw a report by the Army Corps of Engineers considering a submerged dam at Carquinez Strait to keep the denser saltwater from coming in; seawater is denser than freshwater, so the seawater tends to be below and the freshwater on top.

“Almost every conceivable solution has been considered by someone at some point in some way for this Delta over the last 150 years, so there aren’t any new solutions, but there are nice variants,” said Dr. Lund. “Some of the variants might be more suitable for these times than they were for previous times.”

Dr. Brett Milligan spoke about the Reber plan developed in the 1950s by a school teacher. The plan called for filling in half of the bay, channelizing the Sacramento River, and building military and industrial infrastructure.

“Everybody bought into this idea, even the Army Corps,” said Dr. Milligan. “The Army Corps said, this looks promising so let’s test it. So they built a giant physical model to test his theory and found out that it didn’t work, and it didn’t get built for that reason. At the time, given the values, you can see just how far we’ve come in terms of how we think about solutions to the Bay and Delta.”

Karen Kayfetz added that Sylvia McLaughlin, Kay Kerr, and Esther Gulick started Save the Bay as an organization to fight the Reber plan and to fight other plans to fill in the bay. “It was notably an important and largely women-led effort to campaign for what we now cherish as our Bayfront – the recreation, aesthetics – all of that.”

QUESTION: Moderator Karen Kayfetz asked Dr. Brett Milligan to talk about his work in Franks Tract.

He noted that the salinity barrier is a primitive but effective solution; however, there are other impacts, such as impacts to boating, operation of the ferries, and velocities in the Delta. So the Franks Tract project looked at how the geometry of the landmasses and the configuration of the channels could create the same effect without putting in a hard barrier.

Dr. Milligan described Franks Tract as a subsided tract in the middle of the Delta that’s basically a novel tidal lake where salinity comes in. So the project looked at constructing wetlands in a configuration that would create a lot of tidal wetland habitat while also attenuating salinity and doing so in a way that would improve boating and provide recreational features.

“What we were trying to do was bring together all these different elements and trying to attenuate salinity into the Delta in a way that you’re not having to take this barrier in and out and spending vast sums of money,” said Dr. Milligan. “It’s something that could stay out there that wouldn’t prevent boats from traveling through. The routes might be a little longer, but they might be faster because we’d be getting rid of some of the aquatic weeds and other things. The project would provide new recreational features that I think would improve recreation in that area.”

“I think we’re only at the beginning of starting to really think about these kinds of creative ways of how we might reconfigure the Delta and thinking more systemically of like what we can do instead of just trying to put these band-aids on things,” added Dr. Milligan.

Karen Kayfetz noted that Franks Tract is the best example of a planning process for a nature-based solution on the site; however, the project is not funded yet. It was a co-design process involving state agencies with different ways the project could potentially benefit their agency missions. It also included community members representing businesses and recreational interests that could possibly stand to benefit from reconfiguring the tract for more recreational, aesthetic, and economic improvements.

“I think we’re right at the forefront of starting to think beyond just hard engineering solutions,” said Karen Kayfetz, noting that it’s not necessarily the purview of just the Department of Water Resources to plan for a landscape transformation project. “It takes a collaborative approach in order for us to go beyond those myopic single agency missions and think more holistically about how we transform the Delta landscape to serve broader interests than just the preservation of fresh water.”

Dr. Nigel Quinn noted that Bay-Delta Live is a conduit of information on the Delta that increases the confidence of folks on their understanding of some of the functions of the Delta and allows them to shift their positions a little bit and compromise. “Without information, you can’t change your vision or your perspective. … There’s going to need to be some compromise. Not everyone’s going to get what they want.”

Dr. Jay Lund pointed out that there’s very little reason to believe that the best configuration for the Delta and society’s current and future objectives is the configuration we have in the Delta today. He acknowledged that the Delta is tremendously altered from what it was naturally. It was always an evolving place that will continue to evolve as the sea level rises and other things change.

“We should be thinking systematically about the Delta and what we want out of it,” said Dr. Lund. “There’s a wide range of things that we can do to manage not only Delta salinity, but also Delta land use and water quality and ecosystems in particular.”

Dr. Brett Milligan pointed out that part of collaboration needs to consider the current form of governance and how projects are funded in the Delta. “Because if we’re going to move out of our silos into thinking about these things that meet multiple needs, we have really good frameworks for making those move forward. I think we need better ways of doing that.”

Karen Kayfetz agreed, noting that the Delta Science Program recently sponsored a brown bag series on Delta governance. One of the discussion points was that current governance structures do not support the needs that we have, particularly for addressing a changing climate.

“It’s such a multifaceted problem,” she said. “The way that our governance structures are currently set up is largely to deal with one problem per agency. That might be an oversimplification, but that’s how our government is structured. And so, it’s very challenging for us to work on problems like climate change in our existing governance structures. We need to rethink how we collaborate and partner, particularly how we collaborate and partner when it comes to large financial investments in climate adaptation futures.”

Dr. Nigel Quinn noted that the problem also pertains to regulation. The total maximum daily load (TMDL) model that the EPA uses to regulate nonpoint source pollution is an outdated concept that doesn’t take advantage of current information technology. “The police power of governing entities and water agencies needs to be rethought.”

Dr. Quinn suggested a model might be the CV-SALTS program, which is comprised of hundreds of stakeholders working to find the best way of managing salts over the entire Central Valley. “It’s a long-term vision – a 30-year vision. We’re working on the first decade right now. But just in terms of getting everyone to the table and listening to people’s viewpoints, it’s been very successful to date. It’s self-funded to a large extent. So stakeholders, obviously, if they’re putting money in, they want to see results. But that could be a model for moving forward in the Delta.”

QUESTION: What is the impact of salty water on crops?

Dr. Nigel Quinn answered that crops differ in their salt tolerance. Certain crops can tolerate salty water up to a certain point; crop yield declines after crossing a particular threshold.

Dr. Nigel Quinn answered that crops differ in their salt tolerance. Certain crops can tolerate salty water up to a certain point; crop yield declines after crossing a particular threshold.

“Basically, the root system in a crop has to work against osmotic pressures to pull fresh water up into the plant, and the saltier the water, the harder it has to work,” he explained. “Finally, it’s so difficult for the plant it just gives up the ghost.”

Plant breeding has created strains or varieties of crops that are more salt tolerant. “It tends to be that the more valuable crops tend to be the salt-sensitive ones,” Dr. Quinn continued. “The ones the crops farmers like to grow are the ones they’re going to get the most return from, so almonds and crops like that, and to some degree, melons tend to be less salt tolerant. … So it’s that relationship between yields, and income and salinity that farmers are paying close attention to.”

QUESTION: What can farmers do to be more resilient to salinity increases?

Dr. Brett Milligan said that one idea is ‘paludiculture,’ which is growing crops such as rice on wetlands. There’s been a lot of research done from DWR and other folks looking at rice and other crops that can be grown in the Delta under wet and somewhat salty conditions.

Another idea is carbon farming, although Dr. Milligan acknowledged that the market has yet to become viable. Carbon farming can occur on impounded wetlands where they’re not tidal, but there are still levees around them. “You can try to reverse subsidence while also growing wetland plants and tules; it can sequester carbon by pulling it out of the atmosphere. It would help us with the climate change efforts. I think many scientists and agriculturists are looking at new ways of farming, given these changes in conditions.”

QUESTION: What is one knowledge gap that still needs to be addressed, and what would be the benefit of filling this knowledge gap?

“The biggest knowledge gap is knowing what we want, given the complexity of the situation,” said Dr. Lund.

“You sound like a social scientist,” said Ms. Kayfetz.

“We have a very broad view of social science – an unrealistically broad view of social science in the sense that knowing what we want is not a social science question entirely,” said Dr. Lund. “Social science methods can be helpful in assessing that, but knowing what we want is kind of a moral and philosophical thing, as well as a social and political thing. It’s not going to be found by a survey necessarily by itself.”

Dr. Brett Milligan agreed. “What are the potential visions of what the Delta could be? We’ve come around on this multiple times; we have this configuration that the Delta was put into some time back, and it’s not working in many ways. If we take some of the values we have now that are conflicting, there’s a range, but I don’t feel like we’ve really explored it. We can’t keep it the way it is, clearly. What is the realm of possibility that culturally we can even take, interrelate, and think about how we might adapt it to suit our present future needs?”

Dr. Lund pointed out that we have a rich economy relative to where we were at when the Delta was reconfigured. “The sea level is rising, and the climate is changing. And so we should be thinking about the future, what we want, how to get there, and what’s possible to get there.”

Dr. Nigel Quinn noted that we have much more sophisticated numerical and other models and visualization tools that are light years ahead of where it was even ten years ago, so we can render some of these new visions or ideas without building a physical model. But we need to use them carefully and in the right environment, and with robust stakeholder involvement.

“I have a very positive outlook, but it will take time,” said Dr. Quinn. “This is not going to happen in a year or two or in the period of time typically a research grant lasts. So this is a 2030 vision. But I think we’ve got the tools that can really help us.”

Dr. Milligan said that we will have to start discussing retreat, whether it’s reducing the amount of water drawn from the Delta or pulling back from the land. “We assume that we can keep doing things the way we have when as we keep going forward, it looks less and less likely that that will be possible. And that might be our best adaptation thing we have, and we have really no way of going about it yet.”

“We might want to use a word other than retreat,” said Dr. Quinn. “It’s just compromise; it’s just being willing to see the value in doing things a little differently, which it’s not going to be optimal for you necessarily, but it’s going to bring everyone forward and bring people to the table.”

“There’s very little doubt in my mind that we’re going to see retreat, in a sense, very broadly for the Delta and many other aspects of California’s environment,” said Dr. Lund. “We’re going to see some retreat in terms of trying to maintain all of these subsided islands. We’re seeing some retreat in terms of how many native species we can maintain with higher temperatures and tremendously altered ecosystem conditions in terms of invasive species and water quality. We’re seeing some retreat in terms of how much water we expect to export from the Delta.”

“This is the broad societal problem that we have to figure out,” Dr. Lund continued. “Everybody’s going to have to retreat some, and then there will be politics about who retreats and how much. But I think we’re all going to have to retreat; all the interests will have to retreat in one sense or another.”

“Going back to where we started, we need to know what we want to manage retreat,” said Ms. Kayfetz.

“And to know how we’ll get there once we’ve decided,” said Dr. Quinn.

“It’s easy, particularly in the Delta, to say what we want but to specify it in an unrealistic way,” said Dr. Lund. “There’s physics, chemistry, biology, ecology, and economics that limit what we can actually accomplish. There are limits to our ability to manage. And so that needs to be borne in mind as well – not only the direction we want to go but how far we’re actually able to go in that direction.”

QUESTION: What is one action you recommend the state take to address these issues?

“On the technical side, I really think some fairly wide-ranging analyses of water quality in the Delta, not just salinity, but broader water quality, is useful under a wide range of climate change, sea level rise conditions, and Delta island configurations,” said Dr. Lund. “We haven’t been publicly doing a wide range of exploratory analyses on what’s possible and how things interact with Delta salinity. So that’s the technical side.”

“On the policy side and social side, I think real conversations about what we want and how we’re going to have to compromise into the future in a lot of different ways is an important conversation for somebody to sponsor,” continued Dr. Lund. “Perhaps the Delta Stewardship Council will be brave enough to do it.”

“I think rethinking regulation,” said Dr. Quinn. “Regulation and set standards have been convenient in the past, but it tends to be a single issue. And we have a lot of conflicting regulations. For instance, with the Stockton Deep Water Ship Channel, the recommendation was to increase flow through the ship channel into the Delta, yet farmers were being encouraged to conserve more and reduce the drainage into the San Joaquin; these things were completely in conflict. So I think we need to rethink the way we regulate. And we need to do that in a more collaborative and systemic way that looks at the system as a whole.”

“We mentioned Franks Tract and how it’s not funded,” said Dr. Milligan. “I’m wondering if there’s a way that governance can be that it’s envisioning things across agencies from the get-go, so when we go out to those projects, we know that there’s funding, and we know that there’s a mechanism for getting multi-benefit things done. Without them, you try to come up with a solution, and then there’s no constituency for it.”

“We talked about this in terms of permitting or all kinds of things, but greater integration across sectors and what sort of thing could be put in place in the Delta, specifically around adaptation,” Dr. Milligan continued. “A key piece of that too would be how to do it equitably? We keep using the ‘we”, but who the ‘we’ is, is really complicated and hard to get at. So how do we put in a message there to ensure that decision-making is equitable and public?”

CCST_2021_DeltaSalinity_OnePager-2