The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, or SGMA, was passed in 2014 during a period of critically dry years; the legislation was intended to stop the adverse impacts occurring due to the severe overpumping of groundwater basins. SGMA required groundwater basins to form a local groundwater sustainability agency and develop a groundwater sustainability plan to achieve sustainability in their groundwater basins within 20 years. Eight years into implementation, all GSAs have submitted the first groundwater sustainability plans and are beginning to implement them. For SGMA, the rubber is just now starting to hit the road.

The law will most impact the San Joaquin Valley, as most groundwater basins in the valley have been designated as critically overdrafted. At the Urban Water Institute’s annual spring meeting, a panel discussed the challenges that San Joaquin Valley farmers face and how they are responding.

The law will most impact the San Joaquin Valley, as most groundwater basins in the valley have been designated as critically overdrafted. At the Urban Water Institute’s annual spring meeting, a panel discussed the challenges that San Joaquin Valley farmers face and how they are responding.

Seated on the panel were Jason Phillips, CEO of the Friant Water Authority; Dr. David Sunding, an economist and professor at UC Berkeley; and Jack Rice, farmer and consultant.

“In some of these historic years, the Valley has relied on about 8 million acre-feet of not groundwater, but 8 million acre-feet of groundwater overdraft,” Jason Phillips said. “So what the GSAs have in front of them is to try and figure out a way to, by 2040 and starting now, to become not dependent on all of that overdraft. So the panel today will look at the realities of what we’re dealing with in the San Joaquin Valley. And highlight whether it’s been realistic or unrealistic, given the severe economic consequences that will happen.”

Study: The potential impact of implementing SGMA in the San Joaquin Valley

Dr. David Sunding is the Thomas J. Graff professor in the College of Natural Resources at UC Berkeley. From 2013 to 2019, he served as the chair of Berkeley’s Department of Agriculture and Resource Economics. Dr. Sunding set the stage for the panel discussion by presenting the results of his assessment of the effects of SGMA implementation on agriculture in the San Joaquin Valley, as well as other anticipated surface water reductions. The research was done for the San Joaquin Valley Water Blueprint.

This research is the first phase of a two-phase research effort. The first phase is to model the economic impacts of water supply reductions from SGMA and other anticipated reductions in surface supplies with no change in infrastructure and no change in institutions. The second phase would identify measures that would mitigate some of those impacts.

“So, in a way, the policy challenge is to make sure that some of these impacts that I’m going to go through don’t occur and can be mitigated to the extent possible,” said Dr. Sunding.

The first phase lays out the possible outcomes with more or less status quo assumptions about institutions and infrastructure. In the San Joaquin Valley, about 4.4 million acres are being farmed, depending on the year, producing about $20 billion in crop sales; this doesn’t include other agricultural operations, such as livestock industries or dairy. In a typical year, agriculture employs about 165,000 people.

“Given the nature of the semi-arid environment that we live in California, access to irrigation water drives these economic outcomes,” he said. “It simply wouldn’t be possible to produce on that scale without the use of a significant amount of irrigation water.”

There are three main sources of farm water supply in the San Joaquin Valley are:

- water imported from the Delta,

- local surface water supplies, and

- groundwater

Not all of these sources of water are available to all the farmers in the San Joaquin Valley, and all of these sources are expected to decline over the coming decades.

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (or SGMA) was passed in September 2014; SGMA requires agencies that manage groundwater basins to halt overdraft and bring their basins into hydrologic balance by 2040. In January 2020, groundwater sustainability agencies for the basins designated as critically overdrafted submitted their initial plans to the state for how they were going to accomplish this; most groundwater basins in the San Joaquin Valley are classified as critically overdrafted.

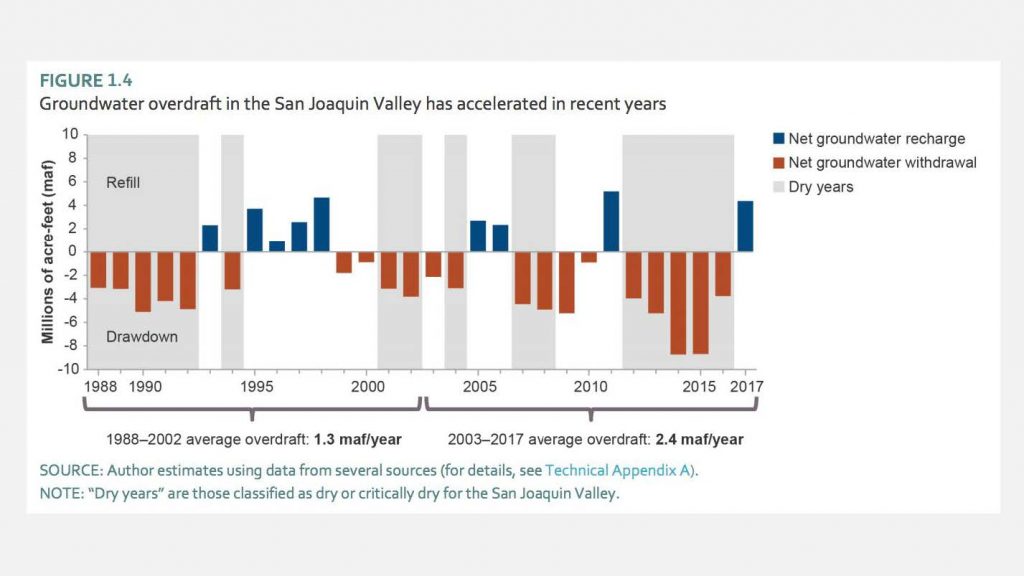

The graph on the slide is from the Public Policy Institute of California, and it shows the amount of overdraft or use in excess of natural recharge for all the basins in the San Joaquin Valley.

“If you look at the 2014-2015 years, which were significant drought years, the estimate is around 8 million acre-feet of overdraft across the San Joaquin Valley in each of those two years,” said Dr. Sunding. “But what this research from the PPIC shows is that the amount of overdraft has increased over the last 30 years or so. The average amount of overdraft from 1988 to 2002 was about 1.3 million acre-feet per year. And then from 2003 to 2017, the average overdraft was about 2.4 million acre-feet per year. So there’s a definite trend of increasing overdraft.”

He also noted that the gray bands are drought years and the white areas are non-drought periods. “What happens is exactly what you’d expect during drought,” he said. “When there’s less surface water available, more groundwater gets pumped by a lot. Then in wetter years, there can be net recharge, although not always. But in general, the trend is increasing overdraft over time.”

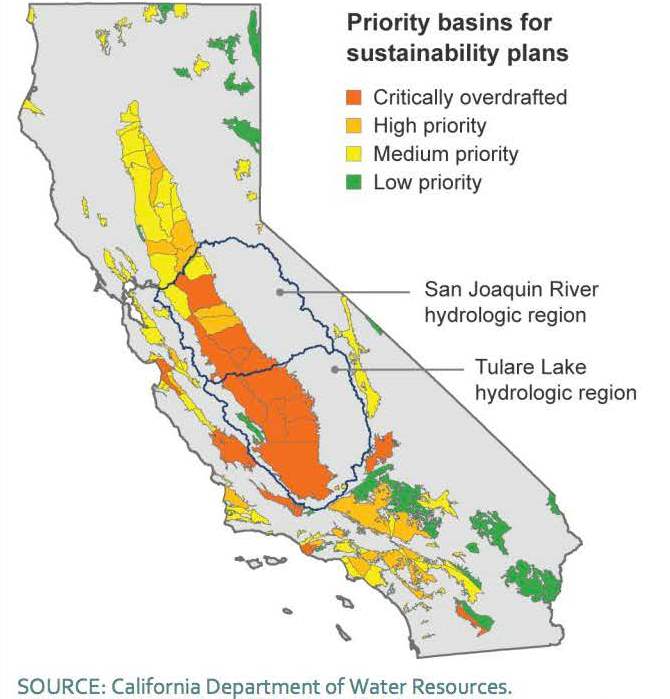

The map shows the groundwater basins across the state. Those shown in orange are critically overdrafted, which encompasses most of the San Joaquin Valley in both the Tulare Lake and the San Joaquin River hydrologic regions. Those basins are prioritized under SGMA and were required to submit their groundwater sustainability plans in January of 2020, two years ahead of the other groundwater basins.

The map shows the groundwater basins across the state. Those shown in orange are critically overdrafted, which encompasses most of the San Joaquin Valley in both the Tulare Lake and the San Joaquin River hydrologic regions. Those basins are prioritized under SGMA and were required to submit their groundwater sustainability plans in January of 2020, two years ahead of the other groundwater basins.

Several things are occurring that will likely reduce the amount of surface water available in the future. These include climate change and sea level rise, which will affect operations and reduce deliveries from the Delta for the State Water Project and Central Valley Project; the San Joaquin River Restoration plan; and then the State Water Board’s update to the Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan.

“So short and long term factors can be reasonably expected to reduce the amount of surface water available to farmers in the San Joaquin Valley,” said Dr. Sunding.

The total water used by farmers in the San Joaquin Valley is around 17 million acre-feet in an average year. Model estimates are that SGMA will reduce groundwater pumping by about 2.4 million acre-feet on average. In addition to that, the Bay-Delta Plan, San Joaquin River Restoration, and sea level rise over the longer term, surface supplies are projected to be reduced by 838,000 acre-feet on average over the study period.

“So if you add the SGMA reductions and surface water reductions together, what we’re talking about is about a 22% reduction in total water use by Valley farmers as a result of reduced ground and surface water supplies,” he said. “So between a quarter and a fifth of all the water that’s available would be gone with both of these measures, and that that clearly is a very large change.”

Part of their research involved determining the extent of the undistricted or ‘white’ areas, which are areas of the valley that don’t have a connection to any surface water distribution system and are completely reliant on groundwater. He acknowledged there’s quite a bit of debate and research about the location and extent of the white areas.

“As part of our work, we did a granular analysis with a lot of ground-truthing about where we think these white areas are and what the extent is,” said Dr. Sunding. “Our estimate is about 820,000 acres in the valley, so that’s 820,000 acres that only have access to groundwater supplies; they can’t use surface water at all. So here’s where the existing infrastructure assumption comes into play.”

“These white areas are the ones that will be the most impacted by SGMA potentially because they don’t have access to the surface water supplies that could substitute for anticipated reductions in groundwater.”

“These white areas are the ones that will be the most impacted by SGMA potentially because they don’t have access to the surface water supplies that could substitute for anticipated reductions in groundwater.”

To estimate the economic impacts of SGMA plus the anticipated reductions in surface water, they modeled how farmers in the San Joaquin Valley would respond to reduced groundwater and surface water supplies.

“Because these reductions require a change in consumptive use to meet the mass balance requirements of SGMA, for example, I think there’s broad agreement that fallowing would be the primary way that would happen,” he said. “Changing irrigation technology doesn’t change consumptive use by much in general, but an increase in fallowing does. And so the assumption is that’s the primary way that farmers cope with reduced surface deliveries and groundwater availability.”

Dr. Sunding reminded that the assumptions of the analysis are that 2.4 million acre-feet of reduced groundwater use and an 838,000 reduction in surface water availability, which equals about a 22% reduction in total water use, which he acknowledged was a very large percentage change.

“When you overlay that with the areas where we expect the changes to occur, we predict that with existing infrastructure and existing institutions, there could be as many as 1 million acres fallowed as a result of SGMA plus expected surface water reductions. So what that means is more than one acre in five would come out of production in the San Joaquin Valley by 2040. That would obviously result in significant land use challenges and other economic effects.”

“In terms of agricultural production and the agricultural economy in the valley … we predict lost revenues of over $7 billion per year in an average year. And lost operating income of just under $2 billion per year.”

Agriculture in the San Joaquin Valley is connected with the economy statewide; farmers purchase inputs produced outside the valley and spend money that they earn from their farming activities in areas outside the valley.

“So taking all these statewide impacts into account, looking at businesses across California, we’re predicting about $3.3 billion in lost operating income annually,” said Dr. Sunding. “Of course, less economic activity means less state and local tax revenue of about $580 million annually, and then lost federal tax revenues of just under $800 million annually. That amount will fluctuate between wet years and dry years, but on average, about $800 million less federal tax revenues annually.”

“Some of the most meaningful impacts that economists measure are job impacts. And that’s particularly true for agriculture. Losing a million acres in production in the valley would result in a loss of about 42,000 farm jobs just in the San Joaquin Valley. And significantly, those 42,000 jobs are associated with $1.1 billion in lost employee income.”

Due to economic linkages between agriculture in the San Joaquin Valley and the broader statewide economy, there are multiplier effects of the total job losses in the San Joaquin Valley. Statewide job losses are estimated at 85,000.

So the total job losses from SGMA plus the expected surface water reductions is about $1.7 billion in lost employee income in the San Joaquin Valley and $2.1 billion statewide. Dr. Sunding noted that many of the job losses occur at the lowest end of the socioeconomic or income spectrum, so the job losses will fall disproportionately on some of the lowest income families in California.

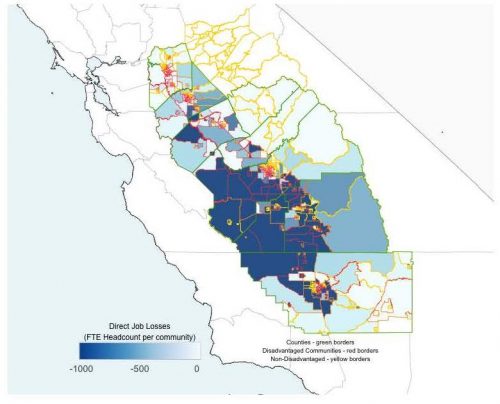

They plotted the location of the expected job losses that would occur from SGMA plus surface water reductions, assuming no change in infrastructure and no change in institutions. The map shows estimated job losses based on where the land is anticipated to be fallowed. On the map, the tracts outlined in red are classified as disadvantaged communities, and the darker the blue, the more job losses are estimated to occur in that particular census tract.

They plotted the location of the expected job losses that would occur from SGMA plus surface water reductions, assuming no change in infrastructure and no change in institutions. The map shows estimated job losses based on where the land is anticipated to be fallowed. On the map, the tracts outlined in red are classified as disadvantaged communities, and the darker the blue, the more job losses are estimated to occur in that particular census tract.

“You can see that the job losses are not equally distributed but would be concentrated among areas in the southern part of the valley,” said Dr. Sunding. “And especially in the southern San Joaquin Valley, almost all of the most disadvantaged census tracts would be impacted by the job losses we’re calculating. … In particular, some of the poorest communities in the southern and western regions of the valley, communities that are already disadvantaged by almost every measure, will lose more than a quarter of all their jobs.”

“In economics, we call this a regressive policy, where it falls disproportionately on people with the lowest income levels,” he said. “The reason that happens qualitatively is that a number of farm jobs have relatively low wages. The people who lose their jobs as a result of reduced water availability tend to be at the lower end of the income spectrum. And I think these results highlight that very clearly.”

The next stage of the study will look at ways to mitigate the impacts, such as increased groundwater recharge, water trading and markets, more surface supplies, using reclaimed water for agriculture, and other things.

The farmer’s perspective: Jack Rice

Jack Rice was raised in a farming family on California’s North Coast. He was an attorney for the California Farm Bureau and then started his own consulting business to assist farmers and ranchers. Mr. Rice currently consults for the Madera Ag Water Association, a group of farmers that are all 100% dependent on groundwater. He also operates a hay and cattle ranch in Humboldt County.

Mr. Rice discussed how farmers are responding to these challenges; his comments focused on two areas: First, what are the issues with SGMA implementation and how is ag responding, and second, how individual farmers are making decisions in response to these issues.

Issues with SGMA implementation

He said the big picture is that there’s a lot of uncertainty. “It’s a perspective of loss for farmers; they’re going to lose something in this process. So while everybody generally understands what has to change, the scale, the pace, and the methods of how those changes are going to be occurring – there’s no clarity on what that looks like.”

“And the reality is, the farmer is going to have a loss associated with less water; it’s going to cost more to get that water, there’s going to be land transitioned out of irrigated production into something else. And for the farmer, they are looking at that whole suite of changes and seeing it will be more expensive, and they’re going to have less income. So it’s a challenging position to be in.”

Mr. Rice acknowledged that the farmers in the valley are not the only ones enduring the effects of water supply, policy changes, and SGMA implementation. There are others – the communities, the environment … but it is a big issue for farmers in their day-to-day decision-making to figure out how to adapt in the face of uncertainty.

Mr. Rice acknowledged that the farmers in the valley are not the only ones enduring the effects of water supply, policy changes, and SGMA implementation. There are others – the communities, the environment … but it is a big issue for farmers in their day-to-day decision-making to figure out how to adapt in the face of uncertainty.

Mr. Rice then broke down the areas of uncertainty.

Groundwater sustainability plans deemed incomplete

The groundwater sustainability plans for the critically overdrafted basins in the San Joaquin Valley were submitted to the Department of Water Resources for review and approval in January 2020. DWR released those reviews in January 2022; many of them were deemed incomplete, which means there will be changes.

“So whatever somebody understood about the groundwater sustainability plan two years ago when the groundwater sustainability agency adopted it – now they don’t know,” Mr. Rice said. “Is that still the same? Or will there be additional changes? There’s just a lot of uncertainty, and uncertainty is very hard for people to grapple with.”

“How do you make decisions? Everything about water supply is trying to gain certainty,” he said.

Undistricted or ‘white’ areas

Those farmers in the undistricted or white areas of the valley are not connected to any water distribution system and don’t have any surface water. So their reductions in supply will come through the implementation of SGMA.

“That means they are going to deal with allocations,” said Mr. Rice. “They haven’t had that before. They’re likely to have a given amount of water to use on their farm or farming operations. And they have to figure out what to do with that. They’re going to have to measure that and pay for every acre-foot in most cases. So they are trying to understand, how do I respond? How will I make these decisions, particularly with the uncertainty of the supply side of groundwater recharge and other factors?”

“There’s just a lot unknown right now, but yet they have to make a decision right now about the future of what they’re doing,” he added.

Water trading and markets

The idea of water trading and markets is out there, and farmers see that as an opportunity. But there’s not a lot of clarity right now on what that looks like. Farmers probably need to have an allocation in place before they can talk about trading and markets thoroughly, he said.

Variation in agriculture across the valley

There is a lot of variation in agriculture in the San Joaquin Valley. And while the undistricted or white areas face significant challenges, they are not the only ones, Mr. Rice said.

“Everybody in the valley is grappling with this,” he said. “There are more senior water rights and less senior water rights in different parts of the valley. There are all types of agriculture; there are permanent crops and non-permanent crops. But understand, in many cases, those non-permanent crops may support a dairy. That dairy is a very significant investment and provides a lot of jobs to the valley. So while it looks like you’re just drying up an alfalfa field or a cornfield, doing that could shut down a dairy worth tens of millions of dollars and employs 100 people, for example.”

Small farmers

Mr. Rice acknowledged there are a lot of large farming operations, but there are also a lot of mid-sized and small family farms.

“When you look at the capacity of people to adapt, it’s very different,” he said. “If you’re a very large entity, compared to an individual farmer trying to run a couple of hundred acres, they may not have an environmental compliance department. They are trying to do that at night after the kids’ basketball game or whatever else they have filling their schedule.”

Many changes besides SGMA

SGMA is coming at a time when there are many other changes, such as changes in labor, air quality, and others. “So SGMA is one more thing being added to their plate,” Mr. Rice said. “It’s complicated, it’s uncertain, and it’s not easy to find your path through this.”

How individual farmers are responding

It can be easy in the panels and discussions about SGMA implementation and policy to think of it as a system, and while it is indeed a system, it’s not an abstract system, he said.

“This is a system comprised of many individual people who need to make decisions for their farm and their operation that will affect their livelihood and the livelihoods of their employees and communities,” said Mr. Rice. “So bearing in mind the issue of uncertainty, it’s just really hard for people right now to know what to do.”

“This is a system comprised of many individual people who need to make decisions for their farm and their operation that will affect their livelihood and the livelihoods of their employees and communities,” said Mr. Rice. “So bearing in mind the issue of uncertainty, it’s just really hard for people right now to know what to do.”

“While SGMA was adopted eight years ago, for a lot of people and for the groundwater sustainability agencies, it’s just now really gotten to the point where they have the information and the bureaucratic infrastructure, if you will, in place to actually begin to implement it,” he continued. “And it’s not because they’ve been going slow; it’s because it’s complicated, and it’s really new for people. And it’s frankly, very difficult to do. So even though SGMA was passed a long time ago, it’s actually just now hitting the dirt.”

It’s also a capacity issue for some folks. “I work with a lot of family farms and on different issues with ranchers, and it is a challenge them … if it’s a family-run operation, they often don’t have the background or the expertise, or even really the capacity to figure out how to adapt to what’s going to come down the road with less water and more expensive water. But they don’t know exactly how much less or exactly how much more expensive it will be, or whether they might be able to do to exchange water with their neighbor.”

“It’s one thing if you have a very big entity,” he said. “They have the capacity to think about these things. They have access to attorneys and engineers to help them come up with good solutions. It’s a whole different deal with a family farm with a thousand acres or more; they don’t have that capacity. There are many folks with farms smaller than that and are really limited. And that lack of economic resources and time puts a huge strain on a lot of our smaller family farms. And that causes me some concern.”

Decreased surface water deliveries

Jason Phillips then discussed the history of Central Valley Project allocations in the San Joaquin Valley. Groundwater levels have declined in the San Joaquin Valley – over 150 million acre-feet of overdraft in the last 100 years, so it certainly isn’t a new problem. In part, the Central Valley Project and State Water Project were built to address declining groundwater levels in the Valley.

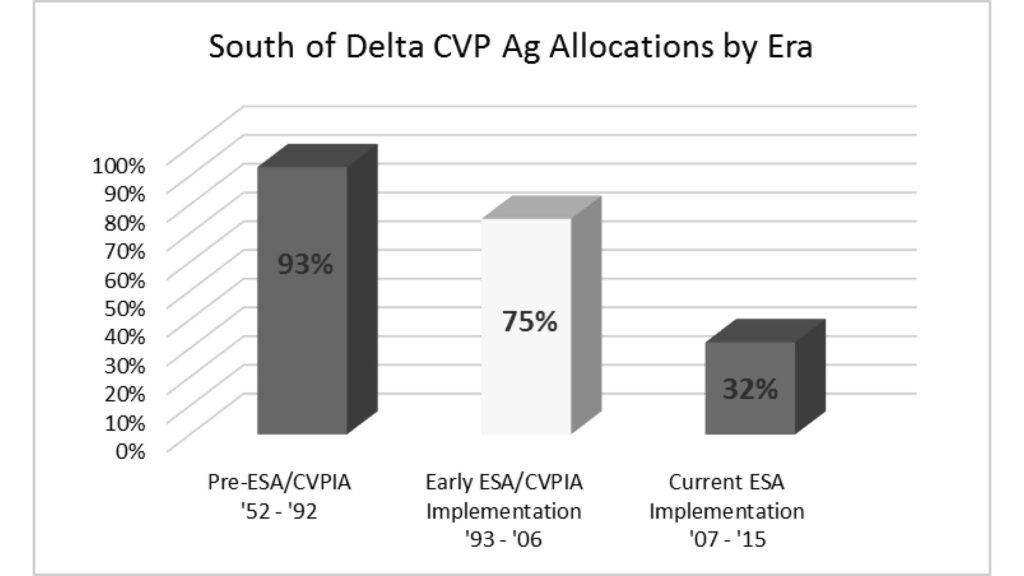

The slide shows how the Central Valley Project allocation has declined over time. When the project came online in about the 1950s, the CVP allocation averaged 93%. Then the Endangered Species Act was passed, so from 1993 to 2006, the CVP allocation declined to 75%. From 2007 to 2015, due to increased regulations of Delta exports, the CVP allocation was further reduced to about 32%.

“In fact, there were regulations that just flat out said, there won’t be an impact from this regulation because we know that the farmers will pump more groundwater to supplement it,” said Mr. Phillips. “Then, in 2014, SGMA was the ultimate regulation that said, well, we’re going to stop that too.”

“We agree that we need to not rely on groundwater overdraft, but this is just to give a perspective of how the problem was supposed to be solved.”

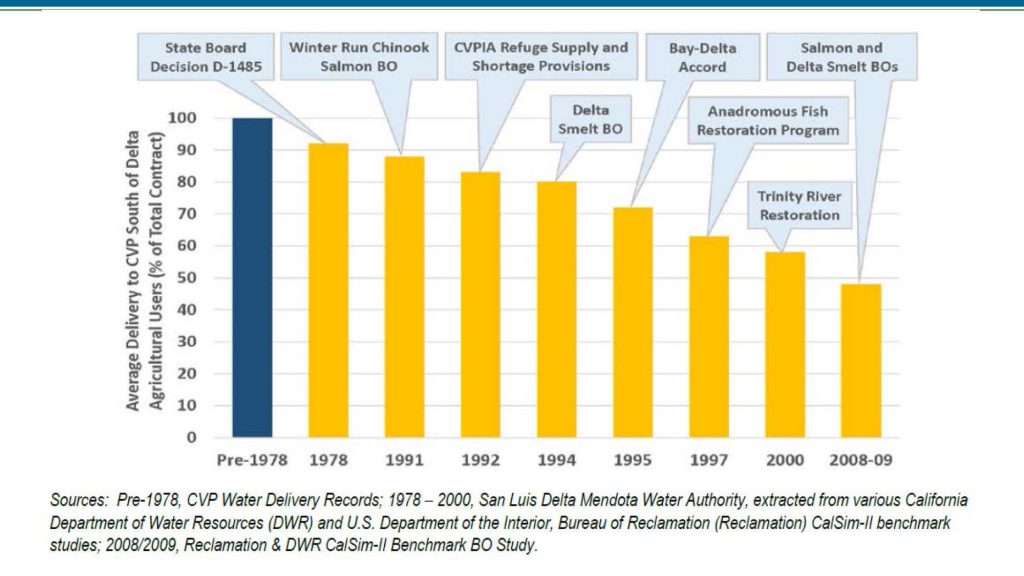

The graph below gives a finer resolution of those increased regulations over time.

“Pre 1978, the Delta allocations to the South Valley were always 100%, even in dry years, and we were seeing an improvement in the groundwater table,” said Mr. Phillips. “One regulation after another, we saw that drop, drop, drop, and we’ve had more subsequent to what is shown on this table.”

“A lot of folks might think that we need to protect the endangered species and water quality, and we agree with that,” he continued. “However, the trajectory of the endangered species has followed probably a steeper decline than this water chart, in terms of overall populations, and so coming from the perspective of those impacted by these decreases, when even more decreases are proposed in the near future, it feels a lot like continuing to do what’s not working. And we bear the brunt of the impact.”

“But at the end of the day, we have to do something to get more recharge water. So what are we doing?”

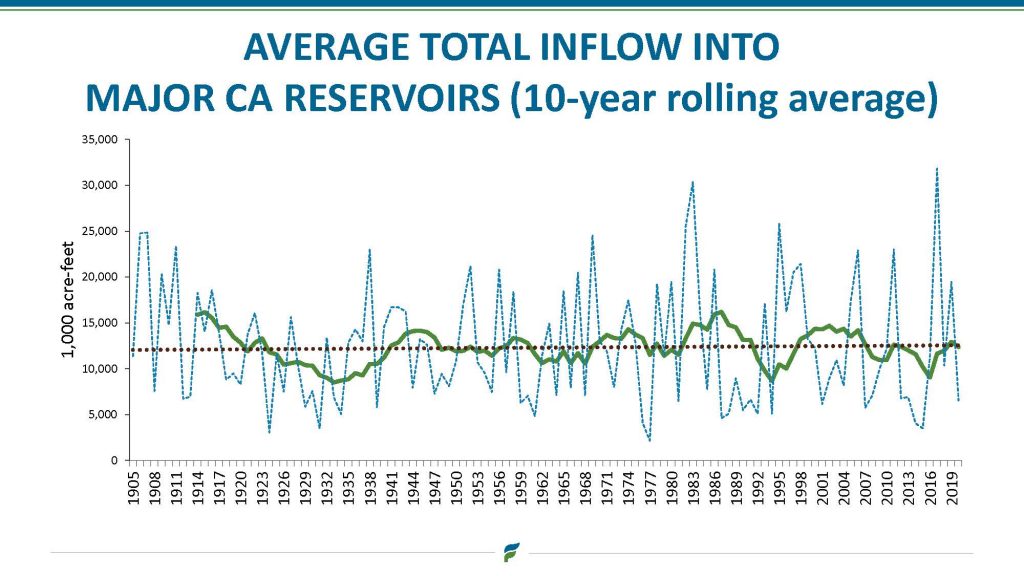

Mr. Phillips noted that we are seeing a shift in temperatures and rising seas, but we do not see a change in the amount of water so far. The slide shows the inflow to the major reservoirs that feed the San Joaquin Valley, including from Northern California.

“If you look at every single year, it’s all over the map,” he said. “This is the variability that engineers have had to deal with the state’s hydrology. But if you look at a ten-year rolling average, it stayed pretty close. We have these really bad drought years, and then we have years where there’s more water. So we need to capture the water when there’s more and find a way to get it in the ground to help when we have to use that groundwater in the dry years.”

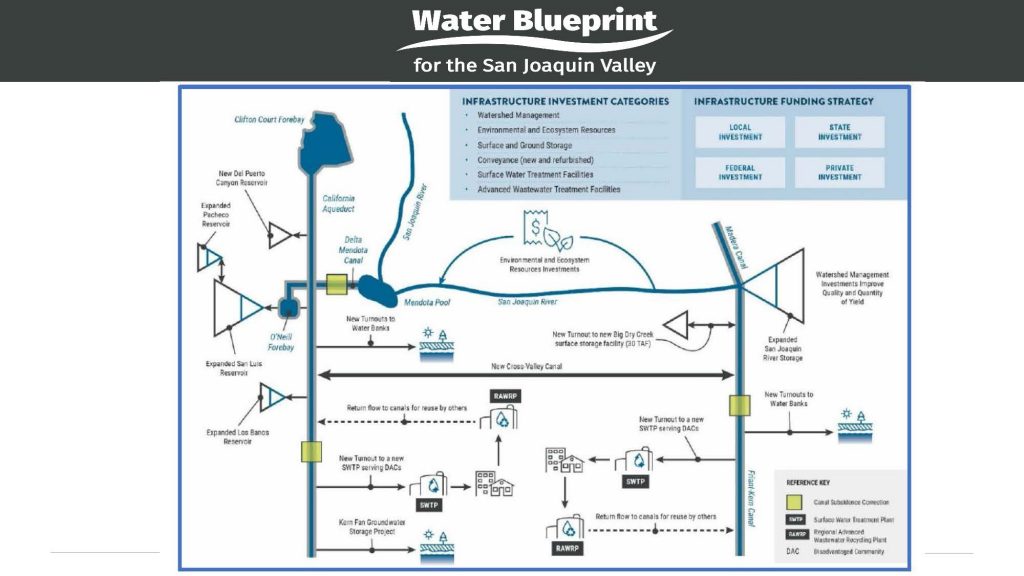

Water Blueprint for the San Joaquin Valley

About three years ago, the Water Blueprint for the San Joaquin Valley effort began to answer the question, can we agree on one set of operations and one set of new infrastructure and improved infrastructure that’s feasible to implement, that we can count on in the somewhat near future so that we can get a better estimate of how much land is going to have to come out of production?

“We have been focused in the last three years on developing the plan that we can all agree with and get behind that is feasible because that’s important,” said Mr. Phillips. “We don’t want just to put out plans that aren’t going to work. In addition to that, we’ve been working on a broader consensus group, where we’ve also invited environmental interests and community interest representatives to broaden that advocacy group to support what projects we need to get recharge water.”

San Joaquin Valley Collaborative Action Program

The San Joaquin Valley Water Collaborative Action Program is another effort to address these impacts built on that vein of collaboration that’s always been part of environmental and water policy. “Sometimes it’s pretty narrow and thin, and sometimes it’s broader,” said Mr. Rice. “This is an effort to expand that over time.”

The Collaborative Action Program grew out of Stanford’s ‘uncommon dialogues’ process. The San Joaquin Valley Collaborative Action Program brings together broad interests generally organized around five groups: safe drinking water and disadvantaged communities, environmental groups, local government, water agencies, and agriculture.

The goal of the first phase was to develop a common problem statement that describes the scale, the water deficit, and environmental needs and create a common solution set of ways to respond that include comprehensive and integrated solutions to achieve sustainability.

On the left, the desired outcomes are listed, such as safe drinking water, sustainable water supplies, the need for improved floodplain and ecosystem health, dealing with the land-use changes from the fallowing, and grappling with the policies that will help inform and shape the solutions. The solutions are shown on the right.

On the left, the desired outcomes are listed, such as safe drinking water, sustainable water supplies, the need for improved floodplain and ecosystem health, dealing with the land-use changes from the fallowing, and grappling with the policies that will help inform and shape the solutions. The solutions are shown on the right.

“It is making sure everyone has safe and affordable drinking water, coming up with strategies to bridge the demand and supply gap that we have, and then investing in these land conversions for habitat purposes and the larger strategies that are going to change what the valley looks like,” said Mr. Rice. “That 20% that Dr. Sunding mentioned – that’s a lot of ground that will look different in the future.”

QUESTIONS & ANSWERS

QUESTION: Is dryland farming and ranching an option?

Jack Rice: “There are several options for land repurposing, and dryland farming is one. Ranching – land may be able to go back into rangeland, as well as renewable energy, solar panels, and habitat. There are a lot of options, but they all have significant economic impacts for the individuals, and that’s why they’re hard decisions to make.”

QUESTION: Are there examples of other states where groundwater management has been implemented? Are there lessons to be learned for California?

Jason Phillips: “Most other states in the country had implemented groundwater regulations well before it became a significant problem like we have today, so we could have learned, but it’s too late.”

Dr. Sunding: “There are certainly examples from around the US. Nebraska is a good example that has some innovative groundwater management policies. In areas around certain rivers like the Platte River, where there is important habitat, they have created different zones where they impose very spatially explicit regulations on how much groundwater can be pumped to try to manage surface groundwater connections and keep that habitat with the right amount of water that it needs. Then there’s a whole water trading overlay. So Nebraska would be just one example.”

QUESTION: Metropolitan Water District pays lots of farmers to fallow as a mechanism to get additional water. Is that possible in the San Joaquin Valley?

Jason Phillips: “In the San Joaquin Valley, I think the expectation and the hope would be that there would be some state and or federal funding to help farmers deal with the fallowing. Of course, that helps potentially the farmer, but in terms of the impact to the communities, the workers, and the state in general, that doesn’t really address that.”

Jack Rice: “The issue of land being repurposed will happen, and part of the value of the funding will be for that to occur better than it otherwise would for the community as a whole, as well as the individual farmers. The farmers hope that there will be some help in making that transition.”

David Sunding: “I know the focus here is on water, but I do want to highlight the land use challenges of the water supply changes that we’re talking about. If the land is to come out of production as a result of SGMA and surface water reductions, that process needs to be managed. You don’t want to end up with a situation where you’ve got a Swiss cheese fallowing pattern; that has issues associated with it, as we found in other parts of the country. But then … what happens to that land if it comes out of farming? Does it become subdivisions? Does it become wildlife habitat, like expanded refuges? Groundwater banking facilities? Could it be renewable energy, such as solar panels? There are all kinds of possibilities, but how you get from A to B, whatever the ultimate use is – that is really an area where I think County and even city governments will have to be very involved. And that is a process that I think will need to be managed.”