“You can’t just dare the board to come after you. You have to pay your fees, and you have to get into these programs.” –Patrick Pulupa, Executive Officer, Central Valley Regional Water Board

In May 2018, the Central Valley Water Board approved the CV-SALTS program to address water quality impacts from ongoing and legacy salt and nitrate accumulation. Implementation of the Nitrate Control Program began in 2020, followed by the Salt Control Program in 2021, issuing Notice to Comply letters to permittees with nitrate and/or salt discharges.

At the April meeting of the Central Valley Regional Water Board, Executive Officer Patrick Pulupa discussed how the Regional Board will begin working towards enforcement actions against permittees who have failed to comply with the Notice to Comply letters for the Salt and Nitrate Control Programs.

The CV-SALTS program is a massive regulatory program, probably one of the biggest things that the Board has done in decades, Mr. Pulupa said. The CV-SALTS basin planning effort resulted in compliance options for permittees that can’t comply with the existing regulations, particularly agricultural, dairy, food processors, wastewater treatment plant sectors, municipalities, and other dischargers.

“Ultimately, what we’re trying to do here is to, where possible, restore water quality within the surface and groundwater of the Central Valley and to meet our long term objectives under the human right to water for safe, clean, and affordable drinking water for every human being in the Central Valley,” said Mr. Pulupa. “Deliberate avoidance of water quality regulations, which is just about occurring under the CV-SALTS programs for non-filers that have received multiple notices to comply, are considered Priority A violations under the State Water Board’s enforcement policy.”

“So what we’re talking about here today is a regulatory program that the Board established to provide a means of compliance for dischargers that were having a very difficult time complying with existing regulations,” he continued. “We have provided them a route of compliance. So those dischargers who have not availed themselves with that particular option and are failing to respond to board notices and directives are on our ‘naughty list’ and deserve to receive the brunt of our enforcement actions.”

Background on the CV-SALTS program

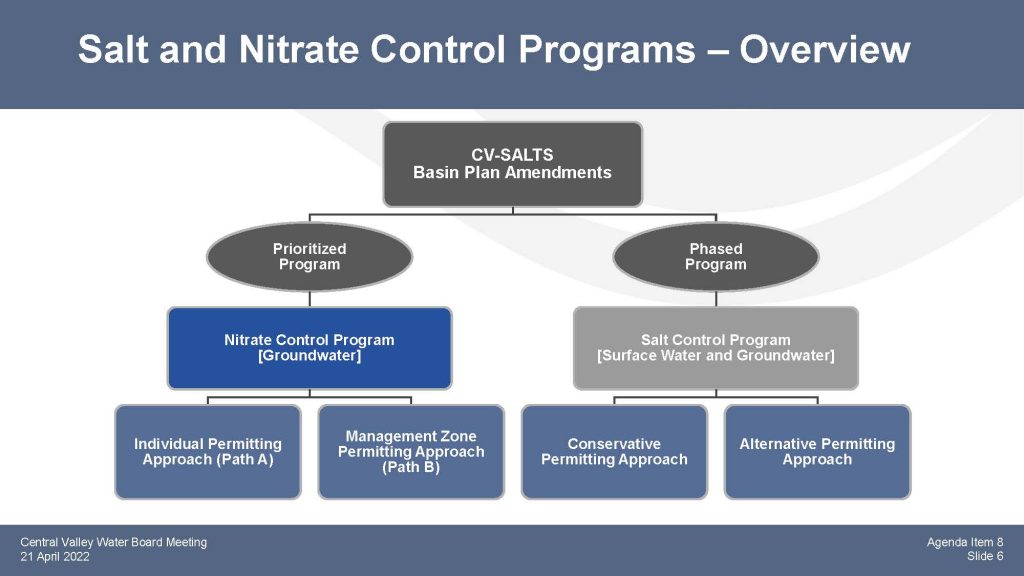

Mr. Pulupa began by discussing why the salt and nitrate control programs were developed. He noted that there were a handful of programs and policies established by the CV-SALTS basin plan amendments, but the two main components are the salt control program and the nitrate control program.

Mr. Pulupa began by discussing why the salt and nitrate control programs were developed. He noted that there were a handful of programs and policies established by the CV-SALTS basin plan amendments, but the two main components are the salt control program and the nitrate control program.

The salt control program was critical because diverse salinity sources throughout the Central Valley were having widespread impacts on groundwater and soils due to the way water is used, particularly in the southern part of the valley. The water quality and economic impacts are widespread: Estimates are about 250,000 acres taken out of production and1.5 million more that are salinity impaired with potential direct annual costs of $1.5 billion up to 2030, largely from land taken out of production but also the ancillary businesses that depend on crops grown on that land.

Nitrate is a water quality issue that is incredibly urgent for many communities throughout the valley, particularly those dependent on groundwater as a source of drinking water. A combination of legacy pollution and existing conditions contribute to this, including fertilizer use, dairies, wastewater treatment plants, and septic systems.

Nitrate is a water quality issue that is incredibly urgent for many communities throughout the valley, particularly those dependent on groundwater as a source of drinking water. A combination of legacy pollution and existing conditions contribute to this, including fertilizer use, dairies, wastewater treatment plants, and septic systems.

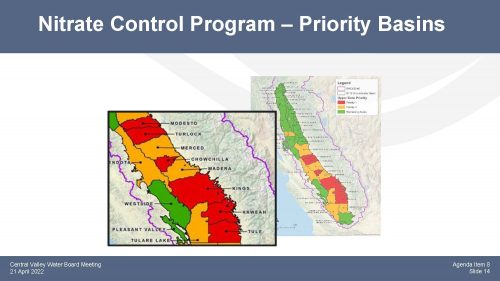

The map shows the areas where there is widespread nitrate contamination of the groundwater aquifer, rendering the groundwater unsafe to drink. Humans, especially infants, that drink water containing more than 10 milligrams per liter of nitrate are at risk of severe and potentially fatal impacts.

“So it’s an incredibly urgent water quality issue that we are called upon to address because realistically, nearly all of these nitrate sources are human-caused,” said Mr. Pulupa. “This is groundwater pollution that we need to figure out how to solve.”

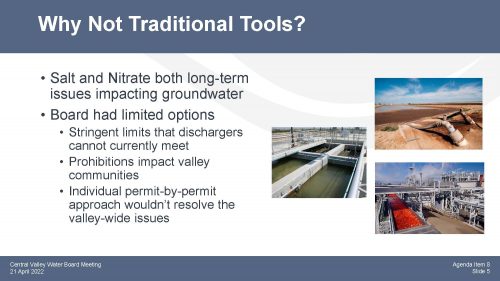

The traditional regulatory approach does not effectively address these constituents as both salt and nitrate are long-term compliance issues. The nitrate issue was not created overnight; much of the nitrate contamination issues have resulted from decades of nitrate leaching into groundwater. Similarly, the salinity problems in the valley are the product of many decades of water use practices within the Central Valley.

The traditional regulatory approach does not effectively address these constituents as both salt and nitrate are long-term compliance issues. The nitrate issue was not created overnight; much of the nitrate contamination issues have resulted from decades of nitrate leaching into groundwater. Similarly, the salinity problems in the valley are the product of many decades of water use practices within the Central Valley.

“So we can’t just apply very stringent water quality limitations to shut off the sources of nitrogen and salinity,” said Mr. Pulupa. “It is not amenable to those types of solutions. It would have huge impacts on the very industries that vulnerable communities rely upon within the valley and would have huge economic impacts. Not to mention that it would negatively impact the agricultural community, which raises many food crops for the entire country.”

He also noted that studies commissioned as part of the CV-SALTS process found that even if the sources of nitrogen and salinity were shut down by forcing businesses to close, it would take 50, 60, 70 years or more for drinking water to meet water quality objectives.

“We want to be able to build a program that meets the needs of the people dependent on nitrate-contaminated drinking water today while we work on those long-term solutions,” he said.

So in 2006, the Central Valley Salinity Alternatives for Long-Term Sustainability (or CV-SALTS) effort began as a cooperative effort among regulators, permittees, environmental interests, and others interested in Central Valley water quality. The result was a prioritized program for nitrate control and a phased program for salt control.

Salt control program

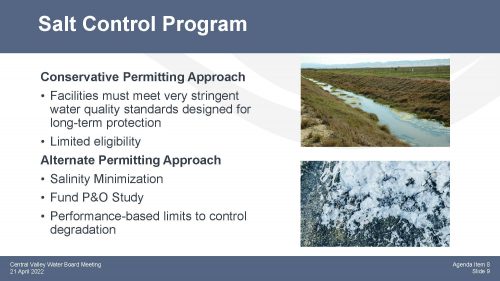

The salt control program has two compliance options that a discharger can choose: either a conservative permitting approach or an alternative permitting approach.

The salt control program has two compliance options that a discharger can choose: either a conservative permitting approach or an alternative permitting approach.

The conservative permitting approach is reserved for those facilities that can meet very stringent water quality standards designed for long-term protection; it has very limited eligibility.

“If you are using water in the Central Valley, in most cases, you are raising the salinity level because salt is a conservative pollutant,” said Mr. Pulupa. “When you apply it to crops, the water goes, but the salt stays. When you recycle water, it gets used up by the plant tissue; the water evaporates and the salt stays behind. The salt always stays behind. If there’s one kind of lesson that you take out of this, it’s that the salt always stays behind unless you develop a management practice to deal with it.”

Stormwater projects and facilities that utilize high-quality source water generally can meet the conservative permitting approach. However, most dischargers, such as most wastewater treatment plants and agricultural dischargers, can’t meet the stringent requirements, so the alternative permitting approach relies on salinity minimization and salinity studies.

As part of the alternative permitting approach, dischargers are funding a $10 million long-term prioritization and optimization (P&O) study which will develop the technical information and roadmap to describe and address the long-term problem of salt accumulation in the Valley.

Dischargers also have performance-based limits to control degradation, so they will be looking at different technologies and solutions to minimize salinity discharges, such as changing water conditioning processes to lower salt alternatives.

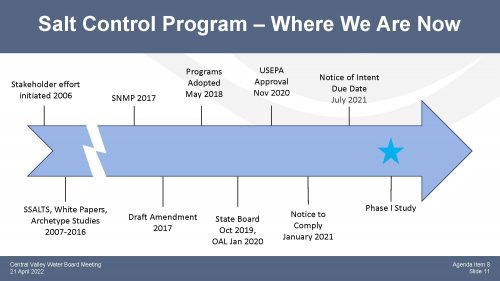

As for the timeline, the CV-SALTS stakeholder-led effort was initiated in 2006. It included strategic salt accumulation studies and white papers that looked at what existing practices were and what existing technology was out there to manage the salts. Those studies were funded from 2007 through 2016 by a mix of state money and money contributed by dischargers.

As for the timeline, the CV-SALTS stakeholder-led effort was initiated in 2006. It included strategic salt accumulation studies and white papers that looked at what existing practices were and what existing technology was out there to manage the salts. Those studies were funded from 2007 through 2016 by a mix of state money and money contributed by dischargers.

The salt and nutrient management plan was developed in 2017, resulting in draft amendments. The CV-SALTS basin plan amendments and regulatory changes that were eventually adopted were built off of that salt and nutrient management plan. The programs came in front of the Board and were adopted as basin plan amendments in May 2018.

The basin plan amendments were sent to the State Water Board and subsequently approved by the Office of Administrative Law in January 2020. USEPA approved them in November 2020, a necessary step for any water quality standard action that affects surface water. The notices to comply were then sent out in January of 2021, with the dischargers’ choice of either the conservative or alternative permitting approach due to the Board by July 15, 2021.

Currently, the program is in the phase one study; everybody is supposed to have responded to the Board and be pursuing one of those regulatory options.

Nitrate control program

The nitrate control program is a prioritized program that results in an individual permitting approach (or Path A) and a management zone permitting approach (or Path B).

There aren’t a lot of nitrate problems in the northern part of the valley, and the nitrate problems in the southern part of the valley are not evenly spread out. So the nitrate control program focuses on a subset of dischargers in the Central Valley in specific areas where the nitrate problems are the worst.

There aren’t a lot of nitrate problems in the northern part of the valley, and the nitrate problems in the southern part of the valley are not evenly spread out. So the nitrate control program focuses on a subset of dischargers in the Central Valley in specific areas where the nitrate problems are the worst.

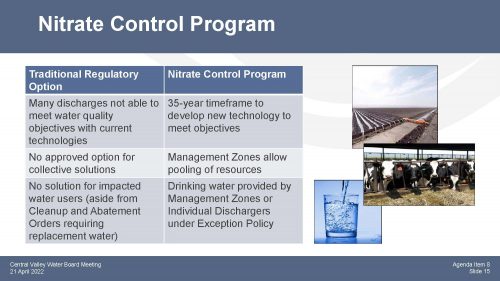

The nitrate control program is a new innovative approach. Under a traditional regulatory approach, dischargers could not meet water quality objectives with current technologies; there still needs to be advancement in the agricultural sector to meet water quality objectives. Dairies need to find new ways of managing their waste to meet water quality objectives to protect drinking water. Septic systems need to be consolidated and require more advanced treatment. Publicly owned treatment works potentially need nitrification-denitrification technologies built into their treatment trains.

The nitrate control program has a 35-year timeframe in which dischargers work together to achieve those goals collectively as opposed to individually.

The nitrate control program has a 35-year timeframe in which dischargers work together to achieve those goals collectively as opposed to individually.

“There’s no approved option for those collective solutions on our traditional regulatory approach,” said Mr. Pulupa. “But the management zone approach, which was one of the innovative components to CV-SALTS, allows the pooling of resources and the collective meeting of those objectives.”

“Also, there’s no solution spelled out for impacted water users aside from individually issuing compliance orders under water code section 13304 under the traditional regulatory option,” he continued. “Under the nitrate control program, that is an expectation. If you plan on utilizing that 35-year timeframe to develop your solution, you also have to take a survey of those communities that may be impacted by nitrate discharges and provide them with replacement drinking water, if you test their facility and you find out that that household or that community is drinking nitrate-impacted water.”

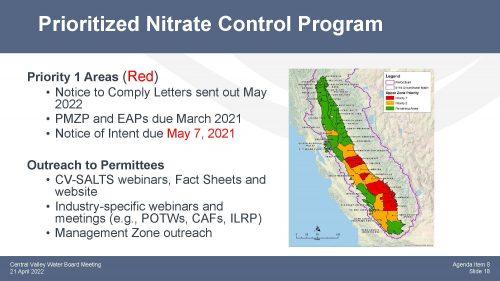

Notice to comply letters were sent out in May of 2020 to the priority management zones. Early action plans were due in March of 2021. Notices of Intent were due back from the dischargers by May 7, 2021. That was also when the Early Action Plans had to begin implementation and start providing replacement drinking water to impacted communities.

Notice to comply letters were sent out in May of 2020 to the priority management zones. Early action plans were due in March of 2021. Notices of Intent were due back from the dischargers by May 7, 2021. That was also when the Early Action Plans had to begin implementation and start providing replacement drinking water to impacted communities.

There has been a lot of outreach to permittees in Priority One areas. Mr. Pulupa noted that this isn’t outreach to communities but rather outreach to permittees informing them of the new program requirements. There were industry-specific webinars and meetings. The Salinity Coalition itself was instrumental in putting many of those together, and they were very well attended. There were specific webinars for POTWs, concentrated animal facilities, and the irrigated lands regulatory program. There was also a lot of outreach done by the individual management zones that coalesced and met with the folks within their areas needing to meet the new regulations.

As for the program timeline, the nitrate program was added to the salt control program in 2012. Similar to the salt control program, there was a study and policy development period from 2012 to 2016. One outcome was studies that found that even if irrigated agriculture and dairies were shut down, the groundwater would not be drinkable for decades in many areas.

As for the program timeline, the nitrate program was added to the salt control program in 2012. Similar to the salt control program, there was a study and policy development period from 2012 to 2016. One outcome was studies that found that even if irrigated agriculture and dairies were shut down, the groundwater would not be drinkable for decades in many areas.

The nitrate program was included in the Salt and Nutrient Management Plan sent to the Board in 2017. The Central Valley Regional Water Board approved draft basin plan amendments in 2018 and the State Water Board in 2019.

Since the program is a groundwater-specific program, it did not need approval by the US EPA, so Notices to Comply for the Priority One areas were sent out in May of 2020. Management zone plans were due in March of 2021. Notices of Intent were due May of 2021.

“That’s where we are now,” said Mr. Pulupa. “If you have not submitted your Notice of Intent, and you’ve got those certified mail receipts coming in from the regional water board, you are eligible for enforcement action from the board.”

“That is key because the final management zone proposals are due in August of 2022,” he continued. “If you’re not participating in this program, you are also not funding replacement drinking water, you are not working with your neighbors to meet the needs of the communities, and you’re not working on nitrate solutions for your discharges.”

The Management Zone Implementation Plans will be due in 2023. Then the Board will begin priority two implementation in those areas that are also nitrate impacted but not as heavily nitrate impacted as the priority one basins.

Compliance and enforcement

Salt control program compliance

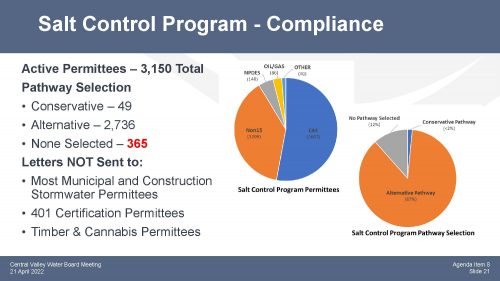

The Notice to Comply for the salt control program was sent to 3150 dischargers, virtually every permittee in the regional Board’s jurisdiction, with some exceptions. Mr. Pulupa noted that those that did not receive notices to comply were municipal and construction stormwater permittees. In most cases, they were found to be discharging below the salinity thresholds for 401 Water Quality Certification permittees. In most cases, they are not moving around water or using water in a way that would exceed those thresholds. With timber and cannabis permittees, the concern is other water quality constituents that are not attendant to this compliance program.

The Notice to Comply for the salt control program was sent to 3150 dischargers, virtually every permittee in the regional Board’s jurisdiction, with some exceptions. Mr. Pulupa noted that those that did not receive notices to comply were municipal and construction stormwater permittees. In most cases, they were found to be discharging below the salinity thresholds for 401 Water Quality Certification permittees. In most cases, they are not moving around water or using water in a way that would exceed those thresholds. With timber and cannabis permittees, the concern is other water quality constituents that are not attendant to this compliance program.

Of the 3150 dischargers who received notices, 49 chose the conservative pathway; those are the very few facilities that can meet the stringent discharge requirements. 2736 chose the alternative compliance pathway, which means they exceed the stringent salinity thresholds and will be participating in the prioritization and optimization study. That leaves 365 dischargers who have not selected a compliance pathway despite receiving multiple notices.

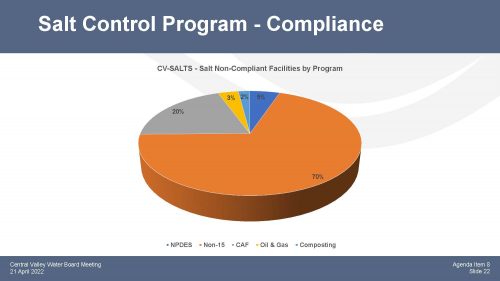

The slide shows the breakdown of those who have not responded. Most of the non-responsive entities are in the “Non-15” program, which is the Waste Discharge to Land Program; these are publicly owned treatment works that discharge to a spray field and food processing facilities. About 20% of the non-responsive entities are in the confined animal facilities unit. The remaining entities are small percentages of composting operations, oil and gas facilities, and NPDES facilities.

The slide shows the breakdown of those who have not responded. Most of the non-responsive entities are in the “Non-15” program, which is the Waste Discharge to Land Program; these are publicly owned treatment works that discharge to a spray field and food processing facilities. About 20% of the non-responsive entities are in the confined animal facilities unit. The remaining entities are small percentages of composting operations, oil and gas facilities, and NPDES facilities.

“These are who we will be targeting with enforcement actions in the month to come for the salt control program,” said Mr. Pulupa.

Nitrate control program compliance

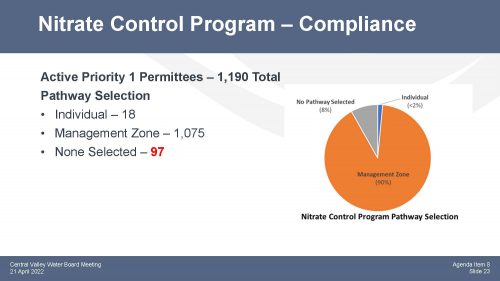

The Notices to Comply were sent to a much smaller subset of permittees; 1190 dischargers in the Priority One areas received Notices to Comply. Eighteen permittees chose the individual compliance pathway; these are food processing facilities with extraordinarily advanced treatment and publicly owned treatment plants denitrifying their effluent.

The Notices to Comply were sent to a much smaller subset of permittees; 1190 dischargers in the Priority One areas received Notices to Comply. Eighteen permittees chose the individual compliance pathway; these are food processing facilities with extraordinarily advanced treatment and publicly owned treatment plants denitrifying their effluent.

Ninety-seven facilities have not yet responded to the multiple notices from the Board, the management zone, and other stakeholders. These notices were sent via certified mail. In addition, multiple notices about the CV-SALTS basin plan amendment process were sent out, so it’s hard to envision a circumstance where they do not actually know about this program, said Mr. Pulupa.

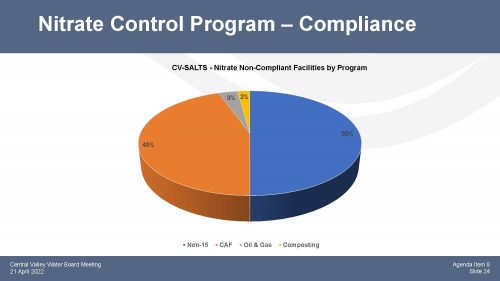

The slide shows the breakdown of those who have not responded by discharger type. About 50% of those are on the “Non 15” program, which are those dischargers with a spray field of some sort. 45% are concentrated animal facilities, and a small number of oil and gas and composting operations comprise the remainder.

The slide shows the breakdown of those who have not responded by discharger type. About 50% of those are on the “Non 15” program, which are those dischargers with a spray field of some sort. 45% are concentrated animal facilities, and a small number of oil and gas and composting operations comprise the remainder.

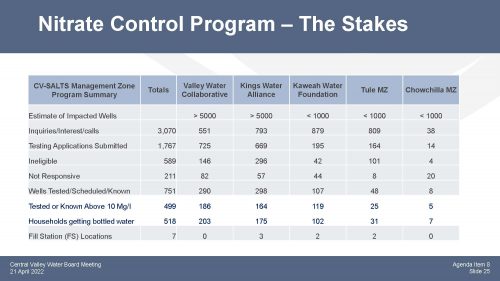

Mr. Pulupa presented a slide with statistics of those impacted by nitrates. The program began in May, and the management zones are working to provide replacement drinking water and free testing to communities that may have nitrate impacts.

Mr. Pulupa presented a slide with statistics of those impacted by nitrates. The program began in May, and the management zones are working to provide replacement drinking water and free testing to communities that may have nitrate impacts.

“Currently, they’re providing about 500 homes with replacement bottled water, and several fill stations have been set up,” said Mr. Pulupa. “At least 2000 testing applications have been submitted, and about 3000 inquiries have come in.”

He noted that folks on municipal water are not being tested because those facilities are regulated under another program.

“If you’re not participating in the nitrate control program, it means that, despite the notices, you are not funding these actions, you are not doing this outreach, and you’re not working on nitrate compliance yourself,” he said.

Staffing and enforcement

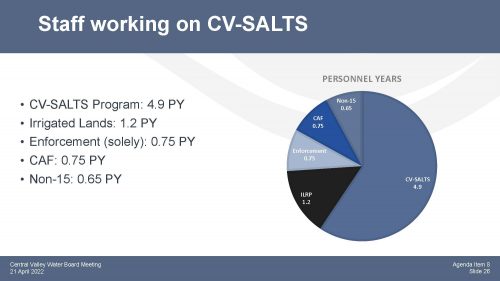

In terms of staff, there are 4.9 personnel years (or 4.9 people) spread out over seven actual people working on CV-SALTS issues. That includes the work being done to get the notices out, stage the meetings, respond to US EPA’s concerns, and manage other regulatory programs that are interfacing with CV-SALTS.

In terms of staff, there are 4.9 personnel years (or 4.9 people) spread out over seven actual people working on CV-SALTS issues. That includes the work being done to get the notices out, stage the meetings, respond to US EPA’s concerns, and manage other regulatory programs that are interfacing with CV-SALTS.

The Irrigated Lands Program has about 1.2 personnel years dedicated to bringing the multiple irrigated lands regulatory program orders in line with CV-SALTS regulations. The confined animal facility program has .75 personnel a year to do work strictly related to CV-SALTS. Those solely related to enforcement are about .7 personnel per year.

“What we are going to do is essentially ramp up those operations as need be to pursue Administrative Civil Liability for non-filers that present a significant threat to water quality and that have actual instructive notice of the program requirements,” said Mr. Pulupa. “So the folks that know or should know about this regulatory program may be facing fines from the Central Valley Water Board to make sure that they do come into compliance.”

The Board will assign a lead to ensure program accountability, including tracking and proposing additional resource needs if needed to track and issue the Administrative Civil Liability complaints. Regular updates on case development will be provided in the executive officer reports so folks can judge how the Board is doing at pursuing these violations.

“We’re going to focus on disadvantaged communities,” said Mr. Pulupa. “Now, the nitrate control program is, by its nature, focused on disadvantaged communities. For the salt control program, the first tier are those salt discharges that are within disadvantaged communities and having an impact on drinking water sources.”

“The bottom line is that the State Water Board’s enforcement prioritization metrics within the state enforcement power priority will treat these as Priority A violations – impacting the integrity of the regulatory program,” he continued. “So that’s basically at the same level as significant spills and requires the same follow-up level for those types of actions.”

Discussion highlights

A board member asked if there is an overlap between the people who are not responding to the salt letters and the nitrate letters.

“Yes, there is,” said Mr. Pulupa. “One of the more complex problems is that there are a number of POTWs in disadvantaged communities that are also not responding to salt and nitrate control programs. We have been meeting with them as much as we can, but that is a kind of dual problem in that these are facilities discharging and impacting their residents through nitrate pollution and salt contamination. So we’re going to be working on, in all likelihood, a separate approach for them and see if we can figure out additional compliance options there.”

A board member asked if there are ongoing conversations with those who are not replying to the notices, or are they just ignoring it?

“It’s the full spectrum,” said Mr. Pulupa. “There are those folks who are in denial that they are causing nitrate contamination and then stop answering our phone calls. Others have just never made themselves available. We have the return receipt that they picked up their mail; they know what’s happening. But they’re just not responding to board inquiries. And those merit enforcement actions.”

Mr. Pulupa recalled that similar enforcement actions were necessary when they initiated the current version of the dairy program. Many folks didn’t sign up for the program, so there were many hearings where the Board had to penalize those people. There were similar enforcement efforts for the Irrigated Lands Regulatory Program.

“You can’t just dare the board to come after you,” he said. “You have to pay your fees, and you have to get into these programs.”

“There’s certainly an issue in terms of equity among our dischargers,” he continued. “We have many dischargers that stepped up and are paying the fee, paying for water testing, paying for bottled water, and will be paying for other drinking water solutions in the years to come. So we don’t want to essentially penalize them by allowing their fellow dischargers to not pay into those programs and not participate in those programs.”

During the public comment period, Michael Claiborne, with the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability, said, “We’re in support of additional enforcement here. I think it’s important to note that CV-SALTS was a proposal by the regulated community. As Mr. Pulupa noted, it allows agriculture, dairies, and other dischargers to continue causing or contributing to exceedances of nitrate water quality objectives for up to 35 years. But this is contingent upon the requirement for responsible parties to provide replacement water and to begin the hard work of coming into compliance with water quality objectives over that period, or in as short a period as is practicable for each discharger or category of dischargers.”

“This structure just doesn’t work if some dischargers decline to participate in the replacement water and nitrate control programs. So for these reasons, we were very supportive of the prioritization of enforcement efforts to ensure that dischargers comply with the notices have to comply and file notices of intent. We ask that staff prioritize important enforcement for those that have not filed Notice of Intent for the nitrate control program in particular, and do appreciate that focus on disadvantaged communities.”

“If it is determined that there’s a need for additional staffing to enforce this program and implement IRLP, dairy, and CV salts, we’d be very supportive of that ask. Just let us know how we can help.”