Attorneys Richard Roos-Collins, Doug Obegi, Jennifer Buckman, and Peter Prows discuss the pros and cons of the voluntary agreements

Voluntary agreements offer a potential alternative to flow standards imposed unilaterally by state agencies on water users. In theory, the agreements are voluntary commitments to both restore habitat and provide certain levels of flows in vulnerable waterways to support aquatic habitat and instream beneficial uses.

Many organizations have spent countless hours working together to craft such voluntary agreements in ways that protect fish and other wildlife and have less negative social and economic impacts than regulatory requirements. But in practice, the voluntary agreements have been contentious, and some question whether they can provide the benefits they promise.

On March 29, State, federal and local water leaders released a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that outlines terms for an eight-year program that would provide flows for the environment, restore habitat, and provide funding for environmental improvements and water purchases. The parties to the MOU are located primarily in the Sacramento Valley in the northern Delta; months earlier, the voluntary agreement discussions for the San Joaquin River were terminated by the state for lack of progress.

Are the promises in the MOU enough? What does it mean if only half of the watershed is covered by the MOU? Would voluntary agreements speed things up or slow things down? At the 2022 California Water Law Symposium, a panel of lawyers with various viewpoints discussed the voluntary agreements.

The panelists:

Richard Roos Collins is a principal with the Water and Power Law Group. He has been involved in many water law issues in California, including the Klamath Basin Restoration and Hydropower Agreements and the Mono Lake Cases.

Peter Prows is a managing partner in the San Francisco-based firm Briscoe, Ivestor, and Bazil. Currently, he represents the Turlock Irrigation District and the Modesto Irrigation District in litigation challenging the State Water Resources Control Board’s decision on the Water Quality Control Plan update for the Bay-Delta.

Jennifer Buckman is a shareholder at Bartkiewicz, Kronick, and Shanahan in Sacramento. She has more than 25 years of experience representing water agencies and water districts in water and land use issues involving the federal and state Endangered Species Acts, federal reclamation and other water supply laws, the California Environmental Quality Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act.

Doug Obegi is a senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council, the NRDC. He’s worked on various projects related to water resource management in California, including the San Joaquin River Restoration Program, the proposed Bay-Delta Conservation Plan/California WaterFix, the Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan review and update, and other state and federal water legislation.

The panel was moderated by Kerrigan Bork, Acting Professor of Law at UC Davis, and organized by the UC Berkeley College of Law.

RICHARD ROOS-COLLINS: Brief overview of the water quality control planning process and the voluntary agreements

Richard Roos-Collins began with the background on the voluntary agreements, which are a proposal to update the Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan. The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (or Bay-Delta) is the largest estuary on the West Coast and the source of water supply for 25 million people. Since the passage of the federal Clean Water Act and the state’s version embodied in the Porter-Cologne Act, there have been five different water quality control plans: 1978, 1986, 1991, 1995, and 2006. This update, initiated by the State Water Board in 2009, will be the sixth iteration of the plan.

Under the Porter-Cologne Act, the Water Quality Control Plan is intended to provide reasonable protection for all beneficial uses of the waters within a watershed or basin. It consists of three parts: designated beneficial uses, such as fish and wildlife or water supply; water quality objectives, which are standards to protect the beneficial uses; and then a program of implementation. The plan includes various objectives that specifically relate to fish, including a narrative objective that requires the doubling of salmon relative to a reference condition.

A program of implementation is not self-implementing, and neither are the objectives self-implementing. So the program itself specifies the authorities that the State Water Board will use to implement the objectives. These include water quality certifications issued under the Clean Water Act Section 401 and other similar orders and water rights pursuant to a decision known as the Racanelli decision in 1986.

To date, the primary sources of flow to achieve the objectives in the plan are the US Bureau of Reclamation through the Central Valley Project and the Department of Water Resources through the State Water Project.

In 2007, the State Water Board decided to update this plan with a real focus on pelagic and anadromous fish as well as salinity in the south Delta. In 2018, the Board adopted an update for the San Joaquin basin that included a new objective that requires 40% of unimpaired flow with an adaptive range of 30 to 50% in order to maintain the native fish in the Delta watershed.

“In the resolution adopting the update, the State Water Board expressly left the door open for voluntary agreements,” said Mr. Roos-Collins. “They said they are being discussed; they are underway. If they are ever submitted, the Board will consider them as a pathway in the resolution approving the 2018 update for the voluntary agreements, even though the agreements were not reached by that time.”

“That update is under litigation. There is also companion litigation with respect to the Biological Opinion under the Endangered Species Act and the Incidental Take Permit under state law. Meanwhile, the State Water Board is heading around the corner to complete the update for the Sacramento River basin.”

At this point, Mr. Roos-Collins noted that while he is the outside counsel for the Natural Resources Agency and the Department of Water Resources, he is speaking entirely in his personal capacity.

“The voluntary agreements are a dream, if you will,” he said. “It’s magical thinking … a dream that began in 2015 under the Brown administration. Various frameworks were reached between 2015 and today. And on March 29, the Newsom administration submitted a signed a memorandum of agreement with a term sheet to the State Water Board to continue in the direction of actually developing the agreements themselves.”

The MOU effectively serves as a proxy for an alternative that the State Water Board might consider in the plan update.

He pointed out that the term sheet is just a term sheet; it’s not an agreement. The voluntary agreements, if they are finalized, will be in three buckets:

- The first is a master agreement that states the relationship between the parties.

- The second is implementing agreements that commit to specific measures at specific places and times and under other conditions.

- The third is government code section 11415.60 agreements, which are agreements under the government code that allows a stipulated decision as the basis for regulatory order.

So the 50,000 plus diverters in the Delta watershed, who might otherwise contest their responsibility to contribute to water quality conditions, enter into an agreement that they sign and specifically agree to the conditions in those agreements. They also agree that the State Water Board may use its regulatory authorities to enforce those conditions, so rather than argue about who has responsibility and litigate it, the Government Code 11415.60 agreements are a mechanism whereby the parties begin implementation immediately.

Since the State Water Board has concluded it does not have direct authority to acquire habitat restoration, the term sheet for the emerging voluntary agreements discusses the integration of flow and habitat restoration. The term sheet also discusses that science will drive adaptive management, which is the State Water Board’s policy. The term sheet elaborates on the science that will be done to assure the effectiveness of the agreements. There is a 15-year check-in to ensure the agreements are working and enforceable.

Mr. Roos-Collins then discussed why he is optimistic about the voluntary agreements. He noted that it’s been roughly 44 years since the first Delta Water Quality Control Plan was adopted, and yet the pelagic and anadromous fish in the Delta watershed are at risk of collapse.

“I don’t say that to fault the regulator,” he said. “So often, these discussions just turn into fault the regulator; that’s easy, but it’s wrong. And it’s also wrong to fault the courts. This is about our system not working adequately to protect the beneficial uses. So our current system in 2022 has not adequately protected the beneficial uses, at least the fishery and wildlife beneficial uses in the Delta, to assure their future.”

He recalled a moment in the Klamath negotiations where the Yurok tribe was face to face with the lead negotiator for the Klamath Water Users Association, which represents 20-plus districts that are federal contractors with the Bureau of Reclamation.

“They looked at each other and said, ‘We’re losing some; we’re winning some, respectively. But our future is getting worse. We are not serving our people’s future through what we’ve been doing.’ And that was the moment when the possibility emerged for what will be the largest dam removal in history. It was that principle.”

“That same principle is here; we need to do better,” continued Mr. Roos-Collins. “We – the people, not the State Water Board by itself; we the people need to do better to regulate and protect the Delta. So we need to integrate flow and habitat restoration. If you go to the Tuolumne, the Stanislaus, the Merced, the Yuba, the Feather – pick your tributary. The last 50 miles, the valley floor – essentially, it’s an abandoned mining field where the native fish get lost and killed by predators, including the striped bass. You can’t just release more flow; you have to address degraded habitat – the 90-95% loss of wetlands in the Delta. So the voluntary agreements are about integrating flow and habitat restoration in the water quality control plan.”

Second, it’s all hands on deck, he said. “Rather than argue about who’s responsible besides Reclamation and DWR, these agreements are intended to bring diverters from all over the Delta watershed together to implement an actual program of flow and habitat restoration measures through these stipulations.”

And lastly, the last key promise is quicker implementation. “We don’t have time for a statutory adjudication of who’s responsible for what in the Delta,” he said. “We need to move quicker than that to restore the Delta. And the voluntary agreements, if successful, would permit early implementation by comparison to what might otherwise occur.”

JENNIFER BUCKMAN: Urban water agencies’ perspective

Jennifer Buckman began by noting that she is currently representing the City of Modesto on their challenge to San Joaquin water quality objectives adopted in 2018 and several cities and urban water districts on the Sacramento River process.

The slide lists some of the important components of the federal Clean Water Act. California’s Porter-Cologne Act implements the delegated authority from the Clean Water Act. The Clean Water Act sets a floor, not a ceiling, so the Porter-Cologne Act sets higher standards for California.

The slide lists some of the important components of the federal Clean Water Act. California’s Porter-Cologne Act implements the delegated authority from the Clean Water Act. The Clean Water Act sets a floor, not a ceiling, so the Porter-Cologne Act sets higher standards for California.

One of the standards that the federal Clean Water Act sets is the requirement to review the standards and update them as necessary every three years. However, in 44 years, there have been roughly five updates to the plan.

“I agree, it’s that’s not a regulatory problem,” said Ms. Buckman. “We have a systemic problem that we can’t complete an update on the plan in the legally required time frame. So when we talk about voluntary agreements being faster than the update process, this is one of the things that I think is most important to note.”

The slide lists some of the Porter-Cologne water quality standards derived from the water code sections. For purposes of the water quality control plan update, the Board is focusing on how to protect the many species in the Delta that are seriously imperiled, such as the salmon and Delta smelt. The longfin smelt is currently listed under the California Endangered Species Act; the federal petition has been pending under the federal ESA for several years; the finding has been listing is warranted but precluded for lack of resources.

The slide lists some of the Porter-Cologne water quality standards derived from the water code sections. For purposes of the water quality control plan update, the Board is focusing on how to protect the many species in the Delta that are seriously imperiled, such as the salmon and Delta smelt. The longfin smelt is currently listed under the California Endangered Species Act; the federal petition has been pending under the federal ESA for several years; the finding has been listing is warranted but precluded for lack of resources.

“We are having some current difficulties in the way that we manage the flow of water through the Delta because the state and federal projects are subject to two different sets of regulations because the longfin smelt is not listed under the federal endangered species act, only under the California Endangered Species Act,” she said. “So when we talk about how difficult it is to do a water quality control plan update or anything in the Delta, it’s because it touches on many of these other laws that all come into play at the same time.”

Phase two involves the Sacramento basin and its tributaries, including the Feather River, Yuba River, the American River, and the Mokelumne River.

Ms. Buckman noted that she has worked on many big settlements on various rivers, such as the San Joaquin River Restoration Program and the Sacramento region’s Water Forum Agreement. “I’ve worked a lot with these flow-based approaches and how we’re going to develop habitat on a river to make it more livable for fish again,” said Ms. Buckman. “As Richard touched on, particularly in the Yuba, the mining history has really influenced the river. So putting water into the river isn’t going to be enough to make it something that can support fish. There’s a lot of physical improvements you have to make to the river too.”

She noted the recent Weyerhaeuser decision where the Supreme Court ruled that land must be habitat before it can qualify as critical habitat. “Before that decision came out, there was no regulation or, or really even policy at the fish and wildlife agencies on the federal level that defined what habitat is. So it was an open question. The Trump administration did issue a rule on this, but it’s being challenged.”

Water temperature is critical for the salmon; they simply can’t survive in water that is too hot. There also must be an adequate passage for juveniles migrating out to the ocean and adults returning to their natal stream to spawn. Coldwater refugia are critical.

“The unimpaired flow approach is the extent of the regulatory authority of the State Board,” said Ms. Buckman. “They can order you to release flows, but they can’t order you to do the physical improvements to the river. That being the case, you’re going to run into problems.”

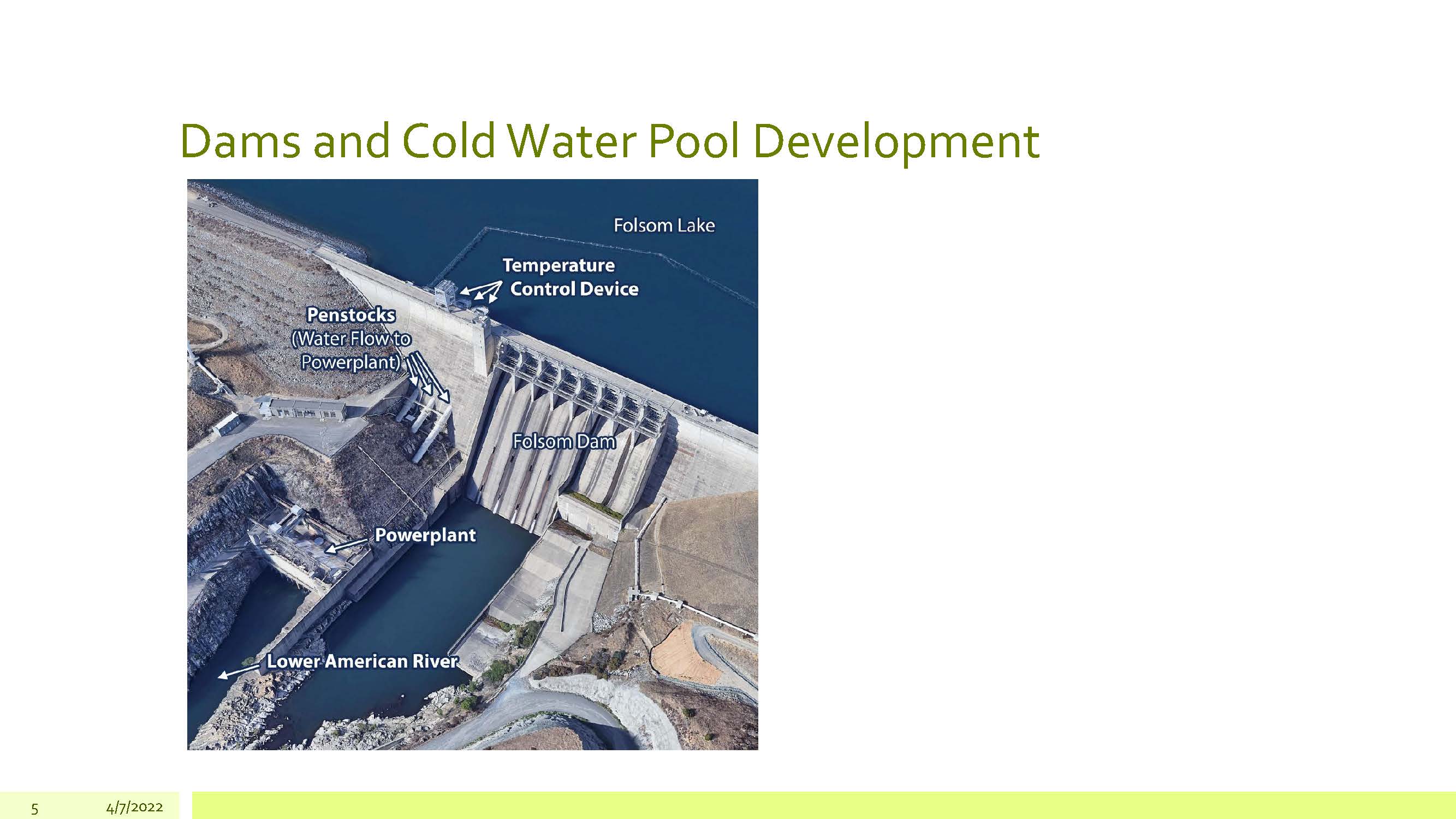

Ms. Buckman presented a picture of Folsom Dam, noting that even though there are temperature control devices on Folsom and Shasta Dam, that alone isn’t enough to create the needed habitat. “In a year like this one, it’s questionable with the low storage in those reservoirs, the lack of snowmelt, and the fact that we’re losing all our snowmelt by the end of April this year – it’s going to be really touch and go on temperature. So that’s a concern.”

Ms. Buckman presented a picture of Folsom Dam, noting that even though there are temperature control devices on Folsom and Shasta Dam, that alone isn’t enough to create the needed habitat. “In a year like this one, it’s questionable with the low storage in those reservoirs, the lack of snowmelt, and the fact that we’re losing all our snowmelt by the end of April this year – it’s going to be really touch and go on temperature. So that’s a concern.”

Another challenge with the temperature at Folsom Dam is Lake Natoma, a downstream reservoir built to regulate the flows released from the dam. The reservoir is flat, shallow, and marrow, which warms up the water before it flows downstream, essentially creating an impassable barrier for the salmon.

The Water Forum is a group of water purveyors, environmental groups, businesses, and the public representing the interests of the American River; they work together to determine which projects will have the most ‘bang for the buck’. The projects are funded largely by the Central Valley Project Improvement Act and implemented with the help of the Bureau of Reclamation and the Department of Fish and Wildlife.

The Sailor Bar project is one such project on the American River completed a couple of years ago. One component of the project was to place gravel in the river. Dams prevent gravel from dispersing as it would naturally during periods of high flow, so projects such as these are important for creating habitat. The slide on the lower right is post-project and shows the redds (or nest of salmon eggs) in the river.

“In terms of achieving the water quality standards, we’re looking to get to a program of implementation and have the VAs be one of the alternative ways of doing that water quality control plan update,” said Ms. Buckman. “The idea is that we have all these tools at our disposal on these rivers; the people who work on the rivers know them better than anyone and can help implement these physical changes faster and create the habitats.”

PETER PROWS: The San Joaquin perspective

Peter Prows began by noting that he is not speaking on behalf of any of my clients, including Turlock and Modesto Irrigation Districts.

Water Code Section 106 states, “It is hereby declared to be the established policy of this State that the use of water for domestic purposes is the highest use of water and that the next highest use is for irrigation.”

Water Code Section 106 states, “It is hereby declared to be the established policy of this State that the use of water for domestic purposes is the highest use of water and that the next highest use is for irrigation.”

“Fish are not on the list, but we water lawyers have found creative ways to get fish on this list,” said Mr. Prows. “This is the bedrock of beneficial use principles that the water quality control plans are supposed to be implementing. The legislature gets to make these calls. First and foremost, they are the trustee of the public trust and didn’t make that call.”

Narrative standards are sort of the ‘all of the above approach,’ where flows are one component of the strategy to promote fish and habitat restoration; temperature is another big one. It is the approach that the Department of Fish and Wildlife supported in the Bay-Delta watershed, and it’s the approach used in the recent Sacramento River Basin voluntary agreement MOUs.

Narrative standards are sort of the ‘all of the above approach,’ where flows are one component of the strategy to promote fish and habitat restoration; temperature is another big one. It is the approach that the Department of Fish and Wildlife supported in the Bay-Delta watershed, and it’s the approach used in the recent Sacramento River Basin voluntary agreement MOUs.

“The San Joaquin basin users have supported this approach,” said Mr. Prows. “But at least for the San Joaquin River, the State Water Board has not. The State Water Board and the state government ended the negotiations with the senior San Joaquin users over narrative-based voluntary agreements. The state walked away from those discussions and, in fact, now takes the position that they can’t legally even talk with water users who are challenging those decisions about settlement directly.”

“Instead, at least for the San Joaquin, the State Board decided to require senior San Joaquin users to implement the unimpaired flow standard from the Bay-Delta update in 2018. They’re doing that through 401 certification orders and the reasonable use doctrine.”

So why unimpaired flow? He noted that the ostensible reason is that it’s being done to benefit fish, but flow doesn’t necessarily equal fish. In developing the Bay-Delta plan update, the State Board used the Department of Fish and Wildlife model, which found that implementing the unimpaired standard would add only 1100 more salmon. They then tried reducing the number of years in the study and found that implementing the unimpaired flow standard would produce a little over 7600 more fish. Contrast that with hatcheries in California, which release 40 million salmon a year.

So why unimpaired flow? He noted that the ostensible reason is that it’s being done to benefit fish, but flow doesn’t necessarily equal fish. In developing the Bay-Delta plan update, the State Board used the Department of Fish and Wildlife model, which found that implementing the unimpaired standard would add only 1100 more salmon. They then tried reducing the number of years in the study and found that implementing the unimpaired flow standard would produce a little over 7600 more fish. Contrast that with hatcheries in California, which release 40 million salmon a year.

“The Sal Sim model, the Department of Fish and Wildlife’s model, showed that increasing unimpaired flows actually decreased salmon,” said Mr. Prows. “Those of us, especially lawyers who don’t understand how models work anyway, can at least come to appreciate that there are bad models and models have their limits. But this is the best model we have. Of course, there are other sources of models, but this is the best model we have. And it just goes to show that it’s not a given that if we just release more water, we can get more fish, and all will be well.”

It’s also important to look at costs. The Tuolumne River is an important economic driver for Stanislaus and Merced counties. Implementing the unimpaired flows is estimated to cost 9,000 jobs, the loss of hundreds of thousands of acres of productive farmland, and $2 billion a year in certain critical dry years. One in five live in poverty in these counties, and one in three families with children lives in poverty. The rapidly growing counties have 50-90% higher unemployment rates than the rest of the state and are 34% poorer. The majority of the population is Hispanic or Latino.

“So let’s not kid ourselves who will be hurt by taking away their water,” said Mr. Prows. “This is an environmental justice issue. Again, all for maybe 1100 or 7500 fish.”

“So what’s really going on here? It’s about water. The State Board’s refusal to negotiate with the senior San Joaquin users is not about fish; it’s about taking their water. Despite California’s record budget surplus, currently $70 billion, the state wants to take senior San Joaquin water rights without paying for it. That’s really what this is all about.”

DOUG OBEGI: The environmentalist perspective

“Our rivers are really impaired by unsustainable water diversions,” began Mr. Obegi, noting that California has variable rainfall and snowpack, wet and dry years, and periodic droughts. We humans have adapted by building dams and levees, but our native fish and wildlife have adapted to the variability.

One of the fundamental things that has changed is the level of water diverted from the system. Unimpaired flow is the term for the volume of water that would flow through the rivers without dams and diversions.

The graph on the lower left shows Delta outflows in 2016. The blue line shows the unimpaired flows; the red line is how much water was captured or stored upstream, and the difference between them is what was captured or stored upstream.

The graph on the upper right is the Tuolumne River in 2015, a drought year. Mr. Obegi pointed out that the Tuolumne is one of the most impaired rivers in California. On average, from 1984 to 2009, 79% of the river’s flow during the months of January to June was stored or diverted; in really dry years, it can be as much as 91%.

“As a result, it’s not surprising that our fish and wildlife are in terrible shape,” he said. “We’re going to watch species go extinct under my watch. My job is to prevent that from happening, and I’m failing.”

The species listed as endangered all have in common a flow abundance relationship that is statistically significant and very strong. “For salmon swimming in the San Joaquin River, in the Tuolumne River, in the Stanislaus River, in the Sacramento River, there’s a strong relationship between the amount of water that flows in the spring and the survival of juvenile salmon swimming downstream. The same is true with respect to water temperature at upstream dams. That’s not just a function of how much water is coming into the dam. It is crucially a function of how much water is leaving the system for farms and cities elsewhere.”

Mr. Obegi pointed out that it’s not just affecting fish and wildlife; it’s behind the harmful algal blooms in the Bay-Delta that are aerosolizing and creating threats to human health and safety in Stockton and some disadvantaged communities.

“There’s a relationship between X2, which is how much water flows through the Delta, and the abundance and distribution of harmful algal blooms,” he said.

Mr. Obegi noted that it’d been stated that the voluntary agreements will be faster, but in fact, over the last 15 years (his entire career), voluntary agreements have been used as an impediment to stop the Board from doing its job.

“In 2013, negotiations were already well underway on voluntary agreements, and they were supposed to be done in 2014,” he said. “Then, in 2014, they were supposed to be done in 2019. And then, in a 2016 letter, they were supposed to be done in 2016. In 2018, they were supposed to be done by March 1, 2019. And then, by March 1, they’re going to be done by spring 2020. So what we’ve seen is a pattern and practice of preventing the Board from doing its job because it benefits those exploiting the resource and are profiting from the level of current water diversions.”

Last month, the Natural Resources Agency submitted the MOU for the Voluntary Agreements to the State Water Board. The picture on the slide was included with the press release. Mr. Obegi pointed out that there are no tribal members, no conservation groups, fishing industry folks, or any Delta communities in the picture.

Last month, the Natural Resources Agency submitted the MOU for the Voluntary Agreements to the State Water Board. The picture on the slide was included with the press release. Mr. Obegi pointed out that there are no tribal members, no conservation groups, fishing industry folks, or any Delta communities in the picture.

“All of us have been systematically excluded from this process since at least 2018,” said Mr. Obegi. “In fact, the participants had to sign confidentiality agreements. And when I requested a copy of the state’s proposal for a voluntary agreement under the Public Records Act, it was denied. They claimed that it was exempt as a gubernatorial communication even though it had come from the resources agency.”

Over the last 15 years, the State Water Board has undergone many peer-reviewed scientific efforts to establish how much flow is needed to protect the environment. In 2010, the Board developed a public trust flows report at the direction of the legislature, and through an open and transparent process, they reached conclusions about how much flow was going to be needed, and it was substantial. In 2012, they did a similar study for the San Joaquin River, and in 2017, they did one for the Sacramento.

“We can all quibble about the science, and in fact, we will always quibble about the science because the incentives are there,” said Mr. Obegi. “Those who make their living from diverting water from the Delta will always be willing to pay to find science that says fish don’t need water. What we see in the voluntary agreements, however, is instead of a process designed, first and foremost, to protect beneficial uses, instead is fundamentally organized around the principle of how much water are you willing to give up? Not what the environment needs, but what are you willing to give up?”

“Part of the reason we haven’t been part of this process is that back in 2016, we told the state, ‘you’re doing this all backward; you should be setting this based on science. What are the fish’s needs, and what are the environment’s needs? And then how do we invest state money to help reduce reliance on the Delta and help sustain the economy? We just got laughed out the room.”

In 2018, the Water Board adopted its framework for updating the Bay-Delta Plan. The framework identified unimpaired flows in the winter and spring months as well as other months, the need to address carryover storage to prevent temperature impacts below upstream dams, and rules on export pumping. It found that it would reduce diversions from the Bay-Delta by about 2 million acre-feet a year; of that total, about 75% was just from winter-spring outflow – and importantly, that’s just from the Sacramento side of the system, Mr. Obegi said. He noted this was in addition to what the Board adopted in December of a 40% unimpaired flow standard for the Stanislaus, Tuolumne, and Merced rivers, which was already down from the 60% that the Board recommended in 2010.

In 2018, the Water Board adopted its framework for updating the Bay-Delta Plan. The framework identified unimpaired flows in the winter and spring months as well as other months, the need to address carryover storage to prevent temperature impacts below upstream dams, and rules on export pumping. It found that it would reduce diversions from the Bay-Delta by about 2 million acre-feet a year; of that total, about 75% was just from winter-spring outflow – and importantly, that’s just from the Sacramento side of the system, Mr. Obegi said. He noted this was in addition to what the Board adopted in December of a 40% unimpaired flow standard for the Stanislaus, Tuolumne, and Merced rivers, which was already down from the 60% that the Board recommended in 2010.

“Yet, behind the scenes, the numbers of the Water Board had just kept shrinking and shrinking under political pressure,” he said. “1.3 million acre-feet combined from the two tributary sides of the system in 2017; 755,000 in 2020, down to less than 500,000 acre-feet of additional flow compared to what was required, or what occurred from 2008 to 2019.”

“If you look closely, you’ll see that the Sacramento River in a critical year, under that C column (referring to the slide on the upper right), is providing a whole 2000 acre-feet of water to help the system, which is less than Putah Creek is providing to the system,” said Mr. Obegi. “Part of the reason why this is so much less is that this latest proposal is now framed around the Trump administration’s blatantly unlawful biological opinions. So the state of California has been suing to overturn those opinions. Yet they turn around and, in this voluntary agreement, say we’re going to add water to those Trump opinions. And because the Trump admin opinions weakened all these protections in the Delta, it resulted in a lot more diversions and a lot less Delta outflow. So when you’re adding water to what was taken away, you end up with a lot less water. And, in wet years and critical years, it looks like it is less water that occurred in 2008/2009 biops with far greater exports from the Delta.”

Mr. Obegi pointed out that the same is true on the San Joaquin side of the system. The VA proposal assumes flows from the San Joaquin – even though there are no parties to the VA from the San Joaquin Basin. But it asked for somewhere between 0% and 84% of the flows required by the 2018 amendments.

“When you look at who signed the MOU versus where the water is coming from, other folks are being asked to subsidize these politically connected water districts who signed the MOU,” he said.

“The same is true with the money. Although according to the MOU, of the money comes from the water district, 75% is coming from federal and state taxpayers. And much of that money is being used for short-term water purchases, meaning that we get no benefit at the end of it from the public’s perspective.”

“The same is true with the money. Although according to the MOU, of the money comes from the water district, 75% is coming from federal and state taxpayers. And much of that money is being used for short-term water purchases, meaning that we get no benefit at the end of it from the public’s perspective.”

“No one has a vested right to unreasonable water use, so there is no obligation to pay water districts to ensure that their use is reasonable and protects the public trust,” Mr. Obegi continued. “We can make social choices whether we should be investing in these communities to help communities adapt to a future with less water. And I think we should be particularly focused on communities and not on the landowners. But that’s not the approach taken here. Instead, this is basically a pay-to-play scheme.”

There are two other critical issues, he said. “One is that the VA wholly fails to ensure that water quality standards are met during droughts. We violated water quality standards in 2014, 2015, 2016, 2021, and now 2022. Every critically dry year since the Brown administration took over, we have not met the water rights obligations of the state and federal water projects. So all the rest of us who don’t have water rights but whose interests are protected by the terms and conditions on those rights just get waived. And there’s nothing in this VA that solves that problem.”

“The second is that this VA just proposes to add some water on top of what already exists but doesn’t actually have strict requirements, even as we’re processing new water rights for diverting more and more water, such as the Sites Reservoir to take more water out of the system. So as we’re adding water with the left hand, we’re also taking water away with the right hand and not ensuring that we’re providing the water that’s needed for the environment.”

“So my opinion, the voluntary agreements have really fundamentally undermined the public trust. They have been negotiated in an exclusionary illegitimate process based on political science, not biological science. It fails to protect the health of the Delta, but it has a lot of political support.”

Some thoughts from Richard Roos-Collins …

The moderator then allowed Richard Roos-Collins to comment. “If the voluntary agreements are as ineffective as Doug just said, they shouldn’t be approved, and if they’re approved, they’ll be vacated, importantly,” he said. “Second, I’ve spent more than 1000 hours in the past five years negotiating with conservation groups on these agreements, and there are ebbs and flows in terms of who’s at the table. Third, with respect to schedule, I’ve never completed a complex negotiation or seen one completed, including prior, which ran on time. I think we missed a dozen deadlines in Klamath until we succeeded. And as I said, we’re on track for the biggest dam removal in history.”

“And lastly, perspective funding,” Mr. Roos-Collins said. “Yes, this is a mix of diverter and other funding, but much like Friant, the Klamath, or what has been done whenever you have to do something that involves the tragedy of the commons – you look for diversity of funding. And so I just encourage all of you to take Doug’s criticisms utterly seriously and keep your eyes open as this process goes forward and form your own opinion once the agreements are actually submitted to the State Water Board.”

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

QUESTION: It seems to me that the state owns the water, and we have a right to use it. But it’s not really private property, so I don’t understand why we would negotiate with private property owners and irrigation districts when it’s really the state’s water. So I’m not sure about the precedent that this sets. …

Richard Roos Collins: “Water is owned by the people; you are one hundred percent correct. Water rights are a proprietary right to use public property. So what we’re doing here is negotiating how those water rights are used. And for me, the single best answer to your question came from the California Supreme Court in the Monterey cases, where the court did reconcile the public trust doctrine with the water code. And it said there very clearly the water code is legal; it’s adopted by our legislature, as authorized in our democracy; it allows diversion of water for hundreds of miles. It is essential for our welfare, our economy, and our future. So those rights that LA holds are legal, but they must be used in a way that avoids unnecessary harm to public trust uses. And so it’s that tension, that reconciliation, which we’re trying to get at here in the voluntary agreements.”

Kerrigan Bork: “I think there’s a lot of debate about how much power the water board has. We’ve had a couple of people say that the water board doesn’t have the power to order habitat work; I think it does. And I’m not alone in that. There are a lot of people who think that it does, and it has, but do we want to litigate that up to the California Supreme Court, and how long would that take? So that’s part of the trade-off this voluntary agreement is. What can you get done more quickly? And I think it’s a very delicate dance to figure that piece out.”

Doug Obegi: “I think one of the real challenges here is that until we start to address the priority of use, we just end up back in the same boat at the end of a voluntary agreement. What we are doing is empowering the water districts to have more leverage to prevent the Water Board from doing its statutorily and constitutionally mandated job. Because of this unequal access to power, and because delay benefits the water districts and not the fish, we have an incentive structure that’s completely misaligned to the goals we’re trying to achieve.”

QUESTION: It sounds like some of the panelists say, let’s do the voluntary agreements. I’d like to hear what the alternative is because I didn’t quite follow that. So, where do we go from here? Are we just going to debate this ad nauseam?

QUESTION: It sounds like some of the panelists say, let’s do the voluntary agreements. I’d like to hear what the alternative is because I didn’t quite follow that. So, where do we go from here? Are we just going to debate this ad nauseam?

Doug Obegi: “The Water Board adopted updated objectives in 2018 for the San Joaquin side of the system. And this voluntary agreement, once it is sufficiently defined, will be, in theory, an alternative for the Board to consider in completing the update of the Bay-Delta Plan, which will happen in the next – in theory, a year or two; in practice; we’ll see.”

“Our view is that the Water Board should be allowed to do its job and move forward with the regulatory process of updating the plan, and then use its authority in the program of implementation to include both regulatory and the water rights adjudication to implement that plan, which also includes 401 certifications.”

“There are challenges with implementing it, but until we actually start dealing with implementation problems, the only other alternative is to end up back right where we are right now, where we have standards that the Water Board and the state agencies and federal agencies have acknowledged are inadequate. And we don’t have the ability to move quickly to update those standards and implement them. … Section 5937 of the fishing game code is one of the longest-standing pieces of California law. … when we became a state, it was illegal to build a dam. And then it was okay to build a dam as long as you kept fish in good condition. So we can use a mix of tools to go after individual diverters and to go after these systemic problems. But ultimately, we think it’s important for the Water Board to adopt the updated plan and do so based on biological science.”

Peter Prows: “Lawsuits. There are going to be lawsuits. When the State Board adopts an approach and a plan that it’s not the approach recommended by the Fish and Wildlife agencies of unimpaired flow and does so over the objections of some of the water users; and then refuses to negotiate with those water users on the San Joaquin about a voluntary agreement and then also refuses to pay for the water that they want to require those users to give up for free, you’re going to get lawsuits. That’s predictable, and that’s why we aren’t there. They’re multiple lawsuits already pending, and there will be more.”

Richard Roos-Collins: “Time matters. And time is getting short for the Delta and for resolving so many other shortages and conflicts. And when we are in a situation like this, the tendency is to point the fingers at the other guy. I personally am not aware of anything the State Water Board said that stopped their process in favor of voluntary agreements. But Doug sees it that way.”

“We point the finger at the other guy. Well, it’s time for all of us to act as though time matters. There is literally a saying in the water bar that a case that matters takes 20 years or longer. As a bar, we have developed an expectation that we should fight for our client’s interest, despite the consequences, despite the time. We have got to change now. There are things that State Water Board could do. There are things that each of us here and each of you could do that would get time back into the equation. So I don’t have an answer, not in the 30 seconds we’ve got left, but I just encourage you to pursue that thought because we have to shorten the time it takes to get one of these water quality control plans in place.”

Jennifer Buckman: “I’m going to be the Debbie Downer here and say climate change because there are many problems we have right now balancing our system and trying to manage it so that we don’t kill fish. We’re going to have even more in the future, and these last two years have shown that. Those water quality standards adopted in December 2018 by the water board, I would argue that based on the last two years of data, they already need to be updated because we aren’t seeing snowmelt that lasts through June. We’re seeing snowmelt the last through April. So an unimpaired flow regime, if you’re trying to mimic that, you’d get a whole different ballgame these days. And that’s why our forecasting has been so off these last two years is because it’s based on historical regression analyses. And we can’t use that going forward. It’s just not working.”

QUESTION: On the issue of delay or timeliness, we heard examples of previously negotiated agreements. One was the settlement of the San Joaquin Restoration, where the judge set a deadline for when the case was going to trial, and fairly promptly, the negotiated agreement was reached. On the other hand, there is the example of the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Act, where the parties agreed to put the State Water Board’s process on the sidetrack, and the negotiations dragged on year after year. Isn’t the best way to get some kind of solution, either a voluntary agreement or a board plan, to set a deadline on the Water Quality Control Plan, adoption, and implementation, so there’s an incentive to finish the voluntary agreement as quickly as possible?

Jennifer Buckman: “I would argue no, having sat through the San Joaquin from July 2003 through September 2006, when we actually signed it, the deadline set by the court was an impediment to making progress – not helpful. What was really helpful was the exchange of expert witness testimony prior to trial, where [a witness] came in for the plaintiffs and acknowledged that the river was going to be too hot without significant habitat improvements. That’s what got the parties moving. Unfortunately, we didn’t finish the San Joaquin settlement until 2009 because of the required federal legislation. So I don’t think that the schedule the judge set was at all helpful.”

Doug Obegi: “I joined NRDC after the settlement had been signed, and my first day at work was meeting with the San Joaquin River Exchange contractors to negotiate the Settlement Act to go to Congress, and they wanted to change the word ‘San Joaquin River’ to ‘conveyance channel’ in the Acts. That was my introduction to California water. So I can’t answer the question of whether having deadlines from the court would incentivize the parties.

“I do think that having the Board move forward creates a powerful incentive to make progress. And in my opinion, the San Joaquin River settlement is not a model. The river will be dried up completely this year because of deliveries to the exchange contractors, precisely because we have an agreement between private parties rather than a regulatory standard that applies to everyone. And it is part of the reason I now much more firmly believe that we need regulatory standards rather than private enforcement as the sole mechanism of protecting the public trust.”

- An update on the Bay-Delta Water Quality Control Plan, a thorough presentation to the Delta Independent Science Board covered on Maven’s Notebook

- State, Federal Agencies Announce Agreement with Local Water Suppliers to Improve the Health of Rivers and Landscapes, press release from the Natural Resources Agency

- San Francisco Bay/Sacramento – San Joaquin Delta Estuary (Bay-Delta) Watershed Efforts, webpage from the State Water Board