Over 600,000 Californians rely on nitrate-contaminated public supply wells for their household water needs. However, those numbers are even greater as they don’t include the many others who struggle with contaminated groundwater from domestic wells. Balancing long-term groundwater sustainability and water quality will help California weather future droughts, ensure safe drinking water, and support our thriving agricultural community that feeds the nation.

One tool for groundwater sustainability is groundwater recharge, where water is intentionally spread on the ground and allowed to infiltrate into the underlying aquifer. However, there is much concern that groundwater recharge can increase water quality issues, especially when the recharge water is spread upon agricultural lands.

In November of 2021, Sustainable Conservation held a webinar featuring a panel of experts who discussed how California can work to replenish our aquifers while protecting water quality for the health of our communities.

First, Aysha Massell, Program Director of Sustainable Conservation’s Water for the Future Program, gave introductory remarks.

Sustainable Conservation is a nonprofit dedicated to helping California thrive by uniting people to solve the toughest challenges facing our air, land, and water. Every day, Sustainable Conservation brings together businesses, landowners, scientists, government, water agencies, nonprofits, and many others to steward the resources that we all depend on in ways that are just and make economic sense, she said.

This webinar discussion focuses on how groundwater recharge and groundwater quality interact with each other. With the passage of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, or SGMA, there has been a growing interest in using groundwater recharge to increase groundwater supplies. Groundwater recharge is the process where water on land seeps through the soils and eventually back into the groundwater table. This happens naturally all the time with rainfall, snowmelt, seepage of rivers, canals, and lakes into the ground below them, and even when rivers overflow their banks and flood nearby land.

Managed aquifer recharge, often called Flood MAR, is a management technique that intentionally uses flood events to spread surface water out onto land to seep back into the ground. Some water districts have been actively managing recharge for years by operating local recharge basins or ponds with good results, but this approach is relatively expensive and limited in geographic impact.

Managed aquifer recharge, often called Flood MAR, is a management technique that intentionally uses flood events to spread surface water out onto land to seep back into the ground. Some water districts have been actively managing recharge for years by operating local recharge basins or ponds with good results, but this approach is relatively expensive and limited in geographic impact.

“Due to the sheer amount of land acreage in agricultural production, the concept of spreading water on agricultural fields has gained a lot of traction in recent years as key to helping us replenish our aquifers at the scale that is needed to address California’s severe groundwater overdraft problem,” said Ms. Massell. “However, many people including farmers, community members, and academics are concerned that contaminants or nutrients on the same fields, such as nitrate, pesticides, and herbicides, may be mobilized by water percolating through the soil, and eventually end up inadvertently contaminating drinking water wells.”

“So today, we bring this panel of experts together to talk specifically about how groundwater recharge projects could potentially harm or improve water quality and community drinking water access,” she continued. “We will discuss how community voices are so important in driving projects and management actions to make sure our work results in the best benefits for people and the environment.”

The panelists:

First, Ms. Massell asked each of the panelists to briefly introduce themselves and their organization and how they came to work in the world of Central Valley Water. In other words, what keeps you motivated each day?

Amanda Monaco from the Leadership Council for Justice and Accountability

Amanda Monaco is the water policy coordinator with Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability. The Leadership Counsel works with about 30 low-income communities of color throughout the San Joaquin Valley and the eastern Coachella valleys on a whole different host of issues ranging from lack of adequate water infrastructure to lack of safe transit and transportation infrastructure, air quality issues, affordable housing issues, affordable energy, land use and permitting of polluting industries right next to communities, and everything that has to do with residents really wanting to create and advocate for safe and healthy places for their families to live.

Amanda Monaco is the water policy coordinator with Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability. The Leadership Counsel works with about 30 low-income communities of color throughout the San Joaquin Valley and the eastern Coachella valleys on a whole different host of issues ranging from lack of adequate water infrastructure to lack of safe transit and transportation infrastructure, air quality issues, affordable housing issues, affordable energy, land use and permitting of polluting industries right next to communities, and everything that has to do with residents really wanting to create and advocate for safe and healthy places for their families to live.

“We got into the water work because all the communities that we work with are either on vulnerable private domestic wells that are going dry all the time and creating a lot of emotional and financial and physical suffering for folks that we work with, or they’re on small community water systems that have their own host of issues,” said Ms. Monaco. “What keeps me going is working directly with residents who just have such innovative ideas and are so passionate and persistent in their advocacy for their communities and their families to have safe places to live. It’s also seeing innovative and forward-thinking people coming together across disciplines to identify solutions that will move things forward and think of solutions that we wouldn’t have thought of if we were just in our own bubble.”

Sue Ruiz from Self Help Enterprises

For over nine years, Sue Ruiz has been working at Self Help Enterprises in Visalia. Self Help Enterprises started as a housing program to help people get into houses and found that they needed to provide water and wastewater infrastructure to communities, so they launched the Community Development Department. Self Help Enterprises now has about 50 employees in the Community Development Department that help mostly small rural community systems deal with water and wastewater issues in nine counties in the Central Valley. Ms. Ruiz works mostly in Fresno County. They also work with domestic well owners to help them deal with their water issues.

For over nine years, Sue Ruiz has been working at Self Help Enterprises in Visalia. Self Help Enterprises started as a housing program to help people get into houses and found that they needed to provide water and wastewater infrastructure to communities, so they launched the Community Development Department. Self Help Enterprises now has about 50 employees in the Community Development Department that help mostly small rural community systems deal with water and wastewater issues in nine counties in the Central Valley. Ms. Ruiz works mostly in Fresno County. They also work with domestic well owners to help them deal with their water issues.

Ms. Ruiz came to California from Illinois to start an outdoor education program. “After four decades in education, I’m now using my teaching thinking to help people deal with their water issues,” she said. “I’m the president of the Eastern Community Services District, which is a domestic well community; that led me to Self Help Enterprises, working with communities and helping people deal with their water issues. And basically, I think what keeps me motivated day to day, because it’s hard work, is just the desire for people to be able to make informed decisions about their needs.”

Taylor Broadhead from Sustainable Conservation

Taylor Broadhead is a project manager at Sustainable Conservation. Her background is in ecology, so her work at Sustainable Conservation has been an introduction to California water, especially in the Central Valley.

Taylor Broadhead is a project manager at Sustainable Conservation. Her background is in ecology, so her work at Sustainable Conservation has been an introduction to California water, especially in the Central Valley.

“I think what keeps me motivated here is being able to do work and bring in the science and then see how it actually gets applied on the ground and getting it into people’s hands so that they can use it for projects and bring about groundwater sustainability,” said Ms. Broadhead.

AMANDA MONACO: Water quality & supply in disadvantaged communities in the San Joaquin Valley

Amanda Monaco began by presenting some statistics to illustrate just how vast and widespread drinking water issues are in the San Joaquin Valley.

“It’s truly a drinking water crisis,” she said. “Around 64,000 people in disadvantaged unincorporated communities receive unsafe drinking water in the San Joaquin Valley. And that doesn’t even include folks on domestic wells. During the last drought, the state received more than 2500 domestic well failure reports; the vast majority of those were in the Central Valley.”

“We know that falling groundwater levels are likely to lead up to 12,000 more wells dry impacting up to 127,000 people,” she continued. “And we know from various studies that drinking water issues disproportionately impact low-income communities and communities of color in the San Joaquin Valley.”

It’s important to recognize these aren’t just statistics; these are actual people whose lives are impacted. One of those is Catalina Garcia from a Central Valley community called Tombstone Territory. Ms. Monaco started working there when they heard that entire streets in the community were having their wells go dry.

Catalina and her family had to spend four months without running water in their home. “She said, ‘I felt sad that my children couldn’t bathe, couldn’t flush the toilet. They were ashamed to go to school because they couldn’t shower regularly, and they smelled. I came here to give them a better life. But even in Mexico, we had running water,” said Ms. Monaco. “She told me, ‘one day my son was using a bucket to shower, and he saved some of the water for me to use, and I cried. Every day, I live in fear that it’s going to happen again.’ People should not have to live with that fear.”

Catalina and her family had to spend four months without running water in their home. “She said, ‘I felt sad that my children couldn’t bathe, couldn’t flush the toilet. They were ashamed to go to school because they couldn’t shower regularly, and they smelled. I came here to give them a better life. But even in Mexico, we had running water,” said Ms. Monaco. “She told me, ‘one day my son was using a bucket to shower, and he saved some of the water for me to use, and I cried. Every day, I live in fear that it’s going to happen again.’ People should not have to live with that fear.”

Families throughout the San Joaquin Valley and elsewhere need water for basic needs, such as drinking, cooking, washing dishes, cleaning, hygiene, bathing, and sanitation. Sanitation is particularly important, especially with the COVID 19 pandemic.

To meet all of those needs, three components must be present:

- It needs to be safe and clean.

- It needs to be reliable and from a consistent source, so if you turn on the tap, water will come out.

- It needs to be affordable. This most basic need that everyone has should be something that everyone can afford to pay for.

In 2012, the California legislature voted that every human being has the right to safe, clean, affordable, and accessible water adequate for human consumption, cooking, and sanitary purposes. So that is now enshrined in California law.

Disadvantaged communities in the San Joaquin Valley are the most vulnerable to falling groundwater levels since they depend on shallow domestic wells and small community water systems. In the San Joaquin Valley, 87% of community water systems are served by groundwater along with all the domestic wells that get water from the ground instead of surface water or canals.

Disadvantaged communities in the San Joaquin Valley are the most vulnerable to falling groundwater levels since they depend on shallow domestic wells and small community water systems. In the San Joaquin Valley, 87% of community water systems are served by groundwater along with all the domestic wells that get water from the ground instead of surface water or canals.

There are three main drinking water challenges for disadvantaged communities: Water quality issues, water supply issues, and unaffordable costs.

Water quality

Water quality issues are numerous and widespread in the San Joaquin Valley. The most common groundwater contaminants are nitrates, arsenic, 123-TCP, DBCP, and chromium-six. The impacts of these contaminants are severe and harmful to human health if ingested, especially over a long period. In the small number of cases where communities depend on surface water instead of groundwater, surface water is not necessarily clean either, as surface water treatment byproducts can be present in the water.

Water quality issues are numerous and widespread in the San Joaquin Valley. The most common groundwater contaminants are nitrates, arsenic, 123-TCP, DBCP, and chromium-six. The impacts of these contaminants are severe and harmful to human health if ingested, especially over a long period. In the small number of cases where communities depend on surface water instead of groundwater, surface water is not necessarily clean either, as surface water treatment byproducts can be present in the water.

The map on the slide is from the State Water Board’s Human Right to Water Portal and shows the cluster of public water systems in the San Joaquin Valley that experience drinking water contamination, shown by the red stars; and the unincorporated communities in the San Joaquin Valley served contaminated water by small water systems, shown in red.

Water supply

Water supply issues are one of the most pressing because if water doesn’t come out of the tap, it’s an urgent situation for families who no longer have water basics, such as cooking, cleaning, and drinking water.

Groundwater levels are steadily dropping in the San Joaquin Valley, even outside of drought years. “There’s a common misconception that wells only go dry during drought years, but in fact, they’re going dry all the time,” she said. “And surface water is also expensive and increasingly unreliable, so that’s not something that folks want to be to have to depend upon.”

Studies have shown that more wells will go dry due to the decline in groundwater levels in the valley. The Water Foundation Report, Groundwater Management and Safe Drinking Water in the San Joaquin Valley, and the website GSPDryWells.com show that somewhere between 9200 to 12,000 wells are estimated to go dry in the next couple of decades due to groundwater decline.

“That’s a lot of homes and a lot of families,” said Ms. Monaco.

Affordable water

There are a lot of costs to address water issues, such as addressing dry wells, treating contaminated water, ongoing operations and maintenance of water systems. She presented a slide detailing the costs, noting that it can cost upwards of $45,000 to dig a new domestic well and up to $1.5 million or more to deepen a community well. Point of use filters are also expensive.

“But despite these obstacles, residents are dedicated to making their communities healthy and safe places for their families to live,” said Ms. Monaco.

Solving drinking water challenges

Ms. Monaco then gave her recommendations for solving community drinking water challenges. First, leverage existing community resources and respect community expertise. Then support with additional expertise and resources. And third, implement projects and policies to address those community needs.

Leverage existing community resources and respect community expertise

Fundamentally, when starting on a path to creating solutions to address community drinking water needs, you have to respect community expertise first.

Fundamentally, when starting on a path to creating solutions to address community drinking water needs, you have to respect community expertise first.

“Respect and listen to community expertise,” said Ms. Monaco. “Create that trust and collaborate with the community at every step of the process. If you don’t, you risk having a failed project or a paternalistic process that instills even more distrust into residents who have, for many decades, seen solutions that don’t work for their communities imposed on them instead of solutions that work with them to really address their needs.”

“They have a lot of community expertise about their needs, their ability to pay, what solutions will and won’t work, creative problem solving – a lot of really great solutions come out of conversations with communities, so ask them, ‘what do you think we should do?’ Folks that we work with also have a lot of expertise about relevant policy processes, who needs to be engaged, what agencies, and how to go about doing that.”

Support with additional expertise and resources

It’s critical to support communities with additional expertise and resources if you have them to lend.

It’s critical to support communities with additional expertise and resources if you have them to lend.

“Every community has different needs, but some potential needs to complement that community expertise to go towards a solution would be funding for infrastructure, community engagement, for research, for technical assistance, like legal assistance or engineering project design and implementation,” she said. “And political capital and really being present in policymaking spaces where decisions are being made that impact community drinking water and showing that allyship with communities.”

Projects and policies to address community needs

And lastly, implement projects and policies to address community needs, such as drinking water infrastructure fixes or multi-benefit recharge. Policies include effective SGMA implementation, preventing the decline of groundwater levels, preventing increased contamination from recharge and groundwater pumping, remediation, and prevention of further contamination from all contaminants, and state legislation to pass things like water affordability programs.

“But again, first, ask the communities what would work best to meet their needs,” reminded Ms. Monaco.

SUE RUIZ: Potential Impacts of recharge basins on domestic wells

How do we solve community drinking water challenges? Ms. Ruiz reminded that it entails leveraging existing community resources and respecting community desires, supporting additional expertise and resources, which is not always easy to find, and implementing projects and policies that help address these needs. However, she noted that it’s a bit challenging regarding recharge efforts.

Ms. Ruiz comes from multiple perspectives. First, she is a domestic well owner herself, living in a community that has approximately 300 to 400 domestic wells. “There is no public water system here for the majority of the community,” she said. “Pretty much everybody’s on their own well, or there’s two, three, or four houses sharing a well, so if a well goes dry, that means four houses may end up without water all at the same time.”

Ms. Ruiz comes from multiple perspectives. First, she is a domestic well owner herself, living in a community that has approximately 300 to 400 domestic wells. “There is no public water system here for the majority of the community,” she said. “Pretty much everybody’s on their own well, or there’s two, three, or four houses sharing a well, so if a well goes dry, that means four houses may end up without water all at the same time.”

She is also the president of the Easton Community Services District, a small community of about 2000 people south of Fresno. “Over the past 60 plus years, the services district has attempted to bring a public water system to the community,” she said. “It is the only agency that can do that because it has the ability to provide services, but the community has denied the public water system approach for all of this time, even during the last drought, the drought in the 70s, and the drought in the 90s. People are not interested in a public water system.”

She has also been at Self Help Enterprises for almost a decade, where she works with the State Water Resources Control Board to provide technical assistance to individuals and rural communities to help them get reliable drinking water; sometimes that’s by abandoning wells and connecting to public water systems. She noted that they recently completed a project just south of Fresno that connected about 60 houses to a water system.

Ms. Ruiz worked extensively with the North Kings GSA in developing their groundwater sustainability plan. “I really pushed hard to make sure that the domestic wells were thought about and reflected on and intentionally included in the plans,” said she said. “There’s still a lot of work to be done in a lot of the GSPs to address domestic well and small rural schools that are served by a single well to help adequately monitor, but we did make some progress. I think that the North Kings is probably going to be a leader with a lot of the GSAs in this work.”

Ms. Ruiz worked extensively with the North Kings GSA in developing their groundwater sustainability plan. “I really pushed hard to make sure that the domestic wells were thought about and reflected on and intentionally included in the plans,” said she said. “There’s still a lot of work to be done in a lot of the GSPs to address domestic well and small rural schools that are served by a single well to help adequately monitor, but we did make some progress. I think that the North Kings is probably going to be a leader with a lot of the GSAs in this work.”

Droughts happen, she said. There have been long droughts, such as the drought from 1928 to 1934; ancient droughts lasted hundreds of years. In the most recent drought from 2011-2016, approximately a quarter to a third of the wells in Easton had to either lower their pump or replace their wells. One of the differences between the ancient droughts and the current drought is an increase in California’s population.

Domestic wells

One of the primary differences between domestic wells and public water systems is that nobody monitors domestic wells; that is up to the well owner. So the well owner has to know everything about their well, such as the quality, the quantity, how deep their well is, where their pump is set, the groundwater level – all of that information that helps them make good decisions about their well.

“Most of us can’t look into the ground and see where the groundwater level is,” said Ms. Ruiz. “How does somebody get that information? They need reliable information so that they can make informed decisions. For example, how fast is the groundwater decreasing? How much time do I have left before my well will go dry? And what do I do about it if it’s happening sooner than I want?”

Domestic well owners also need assistance to drill a new well. It can cost anywhere from $20-45,000 or more depending on where the well is located and how deep it would have to be drilled, and well drillers want that money upfront.

“That’s a lot of money. $45,000 is more than most people’s annual income in the area, definitely in the disadvantaged communities, and it’s very, very expensive,” said Ms. Ruiz. “Even the middle class need financial options like very low-interest loans or other ways to borrow money and pay it off a little bit at a time.”

About 2 million California residents are served either by domestic wells or small systems smaller than 15 connections. The Water Board does not regulate water quality from either of those, so people need information about their water quality, such as how I test it, how much it costs, and what I do if there are issues?

“As an educator, I have a personal mission and passion for getting this kind of information out to people so they can make well-informed decisions about their supply and quality,” said Ms. Ruiz. “They need to learn about what resources are out there and how to utilize those resources. But it’s frightening when you don’t know what to do or who to ask.”

“We also need to increase resources, including availability to that knowledge, and we need to look at some creative funding options. And we need to help people find long-term solutions for their supply and quality, as well as interim solutions like bottled water and the big green tanks [in yards] that you may have seen.”

How can recharge basins help domestic wells? And what are the concerns?

The Fresno Irrigation District built a ponding basin in 2010. Nearby, a well served about 12 homes, and their nitrate levels were very high: 22.5 parts per million in 1978. Ten years after the basin was constructed, the nitrates in the well were at 2 parts per million – a significant decrease, and now the water doesn’t have too much nitrogen. Ms. Ruiz noted it was something discovered by accident.

The Fresno Irrigation District built a ponding basin in 2010. Nearby, a well served about 12 homes, and their nitrate levels were very high: 22.5 parts per million in 1978. Ten years after the basin was constructed, the nitrates in the well were at 2 parts per million – a significant decrease, and now the water doesn’t have too much nitrogen. Ms. Ruiz noted it was something discovered by accident.

Near Okieville in Kern County, the Tulare Irrigation District has a ponding basin that Self Help Enterprises monitored for the effects to nearby wells. The domestic wells were going dry, and Self Help Enterprises measured the distance between the domestic wells and the ponding basin. They found that the wells closer to the ponding basin had less nitrate and uranium. Nitrate levels of domestic wells increased from 8.4 ppm less than 330 feet from the basin to 86 ppm at 2,500 feet away from the basin. Uranium showed similar patterns.

“Both of these are downgradient from the basin, so it appears that the basins really do have some kind of impact on reducing the levels of nitrate in the groundwater,” said Ms. Ruiz.

Fresno Irrigation District just recently placed a new Malaga recharge basin upgradient of Easton, where Ms. Ruiz lives, with the idea of helping water to flow down to Easton. “In terms of water quality, I think it’s far enough away that it won’t impact us, but it might impact some domestic wells between the basin and us,” she said. “We don’t know, but the level of water should be positively impacted by that basin when they can collect runoff.”

Ms. Ruiz pointed out that the state is more willing to fund recharge projects that benefit disadvantaged communities. “That is a carrot that is helpful to Irrigation Districts or GSAs looking at recharge projects; they’re more likely to get funding from the state when they show a benefit to disadvantaged communities, and it’s a good partnership. However, all of this needs to be studied further.”

Could a recharge basin that is downgradient from a community have any impact? Ms. Ruiz asked an engineer working in the Kings Basin, and he said that for a recharge basin that is downgradient from a community, the recharge basin would produce a mound of water, rather than a cone of depression, which could reduce the gradient and slow the movement or migration of a plume that’s upstream.

“Rather than have this rush of the plume through the community to the basin, if the basin fills up, it can possibly keep that plume from flowing into the community,” she said. “In general, he says SGMA is supposed to be monitoring plumes to make sure that whatever they’re doing on groundwater levels isn’t going to negatively impact plumes and the quality of water.”

Ms. Ruiz acknowledged that it’s relatively new, and people are still trying to figure things out. There are not enough monitoring wells in general and not enough monitoring wells strategically located next to domestic well communities. There’s still more work to be done, but in general, surface water brought into the pond can help reduce contaminants and improve the groundwater quality, she said.

Regarding lined versus unlined canals, there is anecdotal evidence that unlined canals boost the water levels in nearby wells. Near Easton, there are a lot of canals that the Fresno Irrigation District put in many years ago. During the last drought, the groundwater level dropped about eight feet; from March to September 2021, the groundwater level in Easton dropped about 10 feet.

Regarding lined versus unlined canals, there is anecdotal evidence that unlined canals boost the water levels in nearby wells. Near Easton, there are a lot of canals that the Fresno Irrigation District put in many years ago. During the last drought, the groundwater level dropped about eight feet; from March to September 2021, the groundwater level in Easton dropped about 10 feet.

“We helped connect folks to the city of Fresno’s water system, and the people whose wells were going dry reported that when the canal, which was about 200 yards from their houses, was full of water, their wells produced a little bit of water,” said Ms. Ruiz. “The drinking water folks were concerned about what that might mean in terms of contaminants rushing into those wells. But the water levels were being impacted just by the canals being full of water. We think it’s very likely that the East Porterville widespread well failure happened because the river was no longer there; the channel to the Tule River didn’t have water for several years.”

“In the past, they started cement lining the canals and closing them up, thinking that that water was being lost,” she continued. “Now we’re rethinking that that water was helping to recharge aquifers. But again, this needs to be studied further.”

It’s important to pay attention to contaminants because a recharge basin could potentially push the contaminant into the community, Ms. Ruiz said. “The hydrological studies and modeling have to be done to determine the impacts to the community. If there’s an existing source of contamination, the polluter should be held accountable. The polluter might need to mitigate.”

“Currently, the state incentivizes recharge basins that help DACs, but are they monitoring or questioning and requiring a study when they fund these things. SGMA is supposed to be paying attention to it and not causing more problems.”

“The other question to think about is if we are going to hold a dairy or construction company accountable, is there another unintended negative impact for the economy and local jobs for ag community? We just have to be aware of those things, even for domestic wells.”

“The other question to think about is if we are going to hold a dairy or construction company accountable, is there another unintended negative impact for the economy and local jobs for ag community? We just have to be aware of those things, even for domestic wells.”

“We also need to think about if a domestic well community should be informed if there’s a basin going in there. Should the domestic well community have input into where those basins go? Right now, there isn’t a real opportunity for that to happen. And if there’s bound to be some contamination, should that basin go in?”

Ms. Ruiz closed by saying that recharge basins impact groundwater levels and quality downstream, so strategically placing them is important.

“We need to have studies to make sure that there are positive and not negative impacts taking place,” she said. “SGMA and the GSAs are supposed to be helping monitor all this, but they’re still trying to get their act figured out.”

TAYLOR BROADHEAD: On-Farm Recharge: Water Quality Considerations & Decision Support Tools

As a project manager at Sustainable Conservation, Taylor Broadhead’s role has two main functions: First, she works with diverse stakeholders to help gather and communicate science related to recharge and how it can be included in management actions; and secondly, she takes the information and works with technical teams to incorporate the science and management practices into decision support tools. In her presentation, she discussed Sustainable Conservation’s work to develop water quality considerations for on-farm recharge over the last year and how they hope to incorporate these into decision support tools.

She began by noting that groundwater use in California is not sustainable, and certain regions of the state are in worse condition than others, so a lot of people have been looking into groundwater recharge as a possible solution. The Public Policy Institute of California (or PPIC) found that, realistically, recharge could probably make up about 25% of the overdraft in the Central Valley, so she noted that groundwater recharge is a really important tool, but not exactly a silver bullet for solving all of our water issues.

There are different types of recharge, such as constructing recharge basins, but this presentation will look specifically at recharge on agricultural fields, also known as on-farm recharge.

“There are a lot of potential benefits of on-farm recharge,” said Ms. Broadhead. “There are also a lot of people who are concerned – and justifiably so – that on-farm recharge has the potential to mobilize contaminants and impact drinking water. But there’s also potential to apply enough water during recharge to possibly dilute what is flushed into the groundwater. So what we’re trying to understand is how on-farm recharge can lead to clean drinking water, or at the very least, prevent water quality problems.”

There are multiple methods of recharge and many different contaminants out there, such as pesticides and arsenic, but Sustainable Conservation’s work is focused specifically on the potential impacts of on-farm recharge on salts and, in particular, nitrates.

She acknowledged that Sustainable Conservation had a lot of help from a wide range of perspectives and expertise, including academics, scientists, irrigation districts, GSAs and their consultants, environmental justice and Conservation NGOs, government staff, and grower representatives.

“As you can imagine, with a lot of different stakeholders, there are really a lot of different perspectives, and sometimes those viewpoints can be conflicting,” she said. “So we were able to address these conflicts by balancing two core principles: The first is that the science is the foundation of the work, but we recognize that the science is not yet settled and it’s still evolving. And second, we want to keep community concerns front and center.”

Sustainable Conservation has produced a white paper that gives an overview of the most current and peer-reviewed literature that forms the scientific foundation on protecting and even possibly improving groundwater quality under on-farm recharge. In addition, there is a nitrate brief targeted towards growers, water planners, and communities which summarizes the nitrate-specific findings from the white paper.

One of the main findings is that nitrate is bad, and it’s likely to get worse in a lot of places in the Central Valley. The map on the slide, produced through the CV-SALTS process, shows the areas of the state in red where nitrate levels are already exceeding drinking water quality standards.

One of the main findings is that nitrate is bad, and it’s likely to get worse in a lot of places in the Central Valley. The map on the slide, produced through the CV-SALTS process, shows the areas of the state in red where nitrate levels are already exceeding drinking water quality standards.

“These red areas are likely to get bigger before they diminish, regardless of management actions like recharge,” said Ms. Broadhead. “A lot of this contamination is due to over-application of nitrogen fertilizer in prior years and even decades. So given that this nitrate has been and still is going to be seeping into the ground, the will still be ongoing nitrate leaching, with or without recharge, from below the root zone.”

One of the most important things from the research found that the most important thing to protect water quality under on-farm recharge is to minimize any further nitrate leaching below the root zone.

“The irrigated lands regulatory program is hopefully ensuring that growers are adhering to best practices,” she said. “But we should also recognize that the work to practically reduce nitrogen leaching on farms is not easily done, and it’s going to take some time. There is still a lot of research, guidance, and tools to be developed.”

The figure is an example of active work to help farmers improve their nitrogen use efficiency that emphasizes the ‘4 Rs’ of nutrient management – which is applying nitrogen at the right rate, at the right time, in the right place, with the right source.

The figure is an example of active work to help farmers improve their nitrogen use efficiency that emphasizes the ‘4 Rs’ of nutrient management – which is applying nitrogen at the right rate, at the right time, in the right place, with the right source.

Sustainable Conservation provides field scale considerations for growers to minimize nitrate leaching under on-farm recharge, such as targeting recharge on crops that have lower nitrate demand, like grapes or alfalfa. These could also be useful for GSAs and irrigation districts in developing guidelines and prioritization tools for recharge.

“GSAs may also want to look at possible cumulative effects of recharge sites in a bigger region or bigger area,” said Ms. Broadhead. “For example, recharge and pumping can result in shifts in groundwater gradients. And this is important to understand for scenarios when you want to avoid flushing nitrate toward a well, or if you want to target recharge to a well so that you can improve water access for communities.”

“When water is limited, as it often is in California, GSAs could prioritize recharge on fewer sites so that they could better dilute some of that legacy nitrate that might be in the soil,” she continued. “Because water is often limited, we thought it would be really useful in this document to include a framework on how you might prioritize sites under on-farm recharge.”

One of the findings of this work is that groundwater quality is likely to worsen before it gets better, regardless of whether there is recharge or not, but the timescale on how that happens can potentially differ with or without recharge. The short-term and long-term potential effects depend on existing water quality and legacy nitrate loading.

The graph below shows how groundwater quality might change with and without recharge across time. In this scenario, there is medium or high legacy nitrate and good existing water quality. The x-axis is time; the y-axis is water quality. The starting point is below the maximum contaminant level, shown by the red line.

“With recharge, which is shown in the blue, you might initially flush some of that legacy and into the groundwater, which causes that initial spike,” said Ms. Broadhead. “But it’s likely to resolve sooner and quicker than in the no recharge scenario, which is shown by the brown band.”

“With recharge, which is shown in the blue, you might initially flush some of that legacy and into the groundwater, which causes that initial spike,” said Ms. Broadhead. “But it’s likely to resolve sooner and quicker than in the no recharge scenario, which is shown by the brown band.”

She explained that the bands are thick because estimating legacy nitrate is really difficult, so there is uncertainty in whether or not the nitrate concentration will exceed the maximum contaminant level. “This is an example of a scenario where you want to exercise some more caution because what we don’t want to do with recharge is worsen water quality that is already drinkable for communities.”

They explored another scenario where nitrate concentration in the groundwater is already above that maximum contaminant level. So this scenario starts above the red line.

“With recharge, we’re likely to flush out and dilute nitrate in the groundwater much sooner than what would have occurred in the no recharge scenario,” she said. “So this situation is one where recharging might be able to help clean up already contaminated groundwater on a much shorter timescale than what otherwise may have occurred.”

Monitoring for impacts of recharge is important, so the framework provides information on identifying sites for monitoring. “We also recognize that funding can be limited for monitoring programs, so it might be helpful to focus monitoring on some of these higher-risk sites,” she said. “That might make sense in some cases where monitoring wells are limited, and our information and data that we’re able to collect is limited.”

Monitoring for impacts of recharge is important, so the framework provides information on identifying sites for monitoring. “We also recognize that funding can be limited for monitoring programs, so it might be helpful to focus monitoring on some of these higher-risk sites,” she said. “That might make sense in some cases where monitoring wells are limited, and our information and data that we’re able to collect is limited.”

Ms. Broadhead acknowledged there are a lot of other great resources available, but they do provide some considerations on monitoring and contingency plans, such as establishing a baseline water quality condition before you do recharge or coordinating monitoring efforts with existing programs like the IRLP as there might be ways to leverage work that’s already been done.

“One thing that became abundantly clear to us through this process is that communities who might be impacted by recharge activities need to be included as decision-makers,” said Ms. Broadhead. “Short term, it could mean 10 to 20 years, which might not sound like a lot. But really, that’s a huge impact for someone who’s relying on groundwater every single day. So this work is really meant to be a tool that can also help communities, as well as growers and water managers, make informed decisions about their water future.”

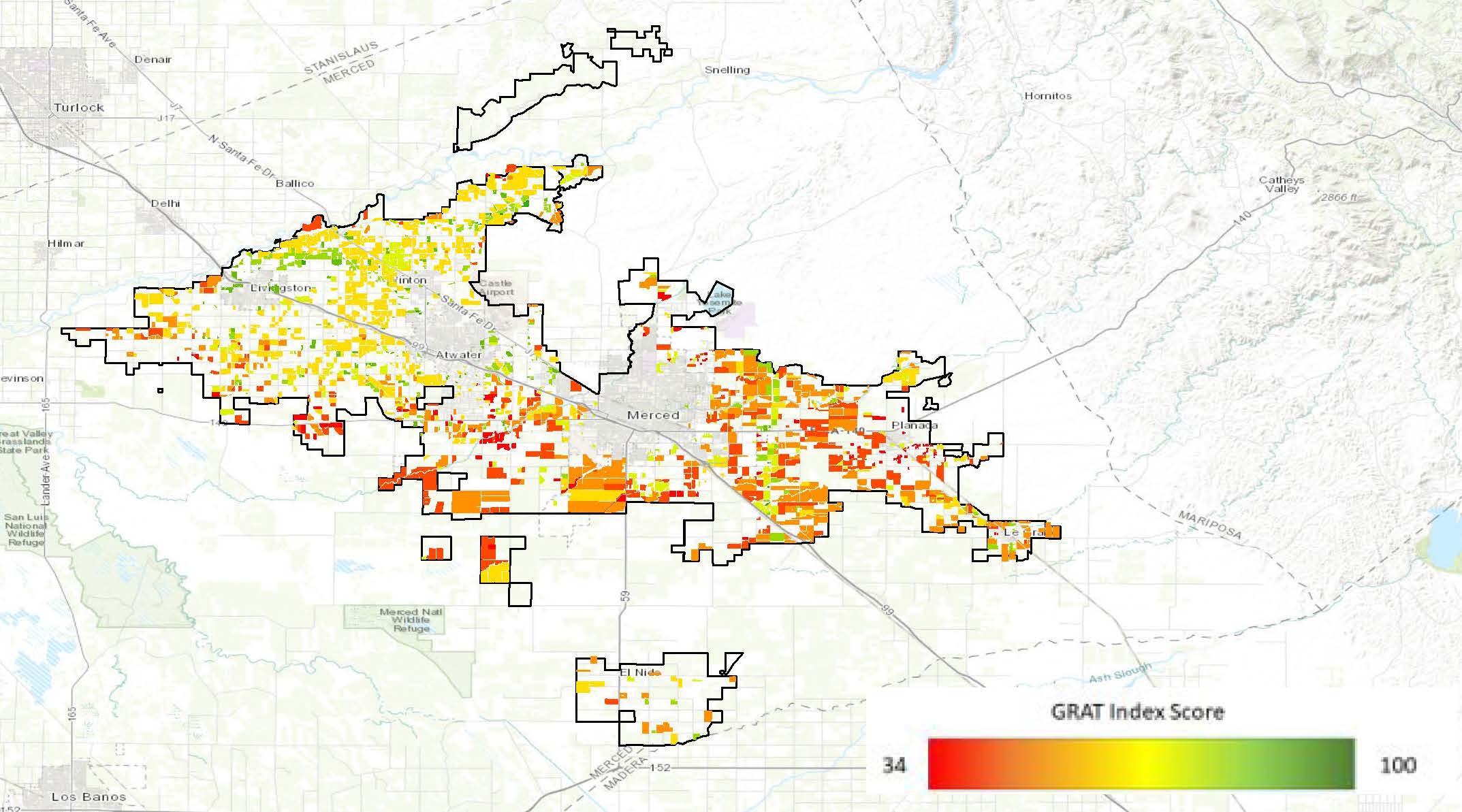

Ms. Broadhead acknowledged there’s still much work to be done to solidify the science and develop tools to support farm recharge. So Sustainable Conservation partnered with Earth Genome to develop the Groundwater Recharge Assessment Tool, or GRAT, for GSAs and irrigation districts. The GRAT tool looks at soils, crops, and other geologic conditions to determine the best sites for recharge, with the primary goal to increase water quantity overall and target the best sites for getting water into the ground.

Ms. Broadhead acknowledged there’s still much work to be done to solidify the science and develop tools to support farm recharge. So Sustainable Conservation partnered with Earth Genome to develop the Groundwater Recharge Assessment Tool, or GRAT, for GSAs and irrigation districts. The GRAT tool looks at soils, crops, and other geologic conditions to determine the best sites for recharge, with the primary goal to increase water quantity overall and target the best sites for getting water into the ground.

“What we found is that these sites that are best for getting water into the ground in terms of percolation may not always be in places where you might need to do recharge the most – for example, to deliver water for communities,” said Ms. Broadhead. “There’s some really cool work being done with this decision support tool to start targeting recharge to achieve different management objectives, like replenishing groundwater that serves disadvantaged communities or ecosystems, for example. So now we’re trying to work out how we can include these water quality considerations, principles, and decision support tools for recharge. There’s definitely work to be done on collecting and refining the data and methodology that can make this happen. But the potential here is really exciting.”

For the next steps, they are to incorporate a management area concept for water quality and decision support tools. More outreach to GSAs, irrigation districts, farmers, and communities is planned. And they are working to incorporate this guidance into supporting recharge program development on the ground.

QUESTIONS & ANSWERS

QUESTION: How can we take what we know about groundwater recharge and water quality and use it to plan for projects that are protective of water quality? How do we incorporate water quality into recharge projects?

“One piece is really understanding what the historic land use has been,” said Taylor Broadhead. “It’s really hard to estimate how much nitrate might be in the vadose zone underneath the root zone and how much legacy nitrates are there. We might be able to do that by understanding what the historic land use has been and looking at what crops may have taken more nitrate in the past. Another thing could be if we can get more specific information about what nitrate application records have been, so that for the districts interested in doing recharge, really trying to target water to where there is less of a risk of flushing nitrate into the groundwater, I think is really key.”

QUESTION to Ms. Monaco: You mentioned that what gets you motivated every day are innovative solutions that people are coming up with. Can you talk about some of the solutions that the people most affected by drought and water quality? What are some of the solutions that they are suggesting on the ground for their particular communities?

“The first solution that most folks that we work with want is to stop groundwater overpumping near their communities,” said Ms. Monaco. “They see the direct correlation between what happened in Tombstone Territory and Fairmead and many other communities – the direct correlation between new almond fields being planted right next to their communities, and their community wells and their domestic wells going dry. So first and foremost, doing whatever we can to protect the groundwater levels under communities and keep them high.”

“The second big proposal from communities is having drinking water mitigation programs, so if wells do go dry, there are readily available programs and agencies who are responsible and accountable to those impacts and will either connect them to a local water system, deepen their well, or give them emergency bottled water,” she continued. “And third, having these projects like land repurposing or groundwater recharge right next to communities that can provide additional benefits. Folks in Fairmead and Lavinia in Madera County have had really innovative ideas about how to do land repurposing and recharge in a way that creates green space, protects habitat, creates habitat, and also protects community drinking water.”

QUESTION: Some communities, when faced with dwindling water supplies, potentially have a choice to connect to nearby water systems, but they choose not to. Why is that?

“There are a couple of reasons,” said Ms. Ruiz. “There is the freedom to make choices for yourself and not be under some government or somebody else telling you what to do with your water. What helped me educate the community that connected to the city of Fresno when we first were working with them was water quality … It’s really hard to convince the 95-year-old who has been drinking water all his life that the water is going to kill him. That’s a hard, hard sell. But when the wells started going dry, people were willing to connect to the city. We educated them on the cost of drilling a new well, bringing in bottled water or putting in a point-of-use filter which is expensive, versus a monthly water bill for reliable water. So just helping people look at the dollars helps them make that decision.”

QUESTION: Anyone trying to get information about the state of domestic wells has run into issues; it’s hard to get this data from public sources, and part of that is due to privacy and security reasons. People don’t want others to know where their well is located. And also freedom – I don’t want other people to be nosy about my water. But planners and others such as nonprofits or consultants really need this information to serve domestic wells. So how do others access the information while keeping people’s information safe? Do you have any ideas on that?

“When we do our work, if we test wells, we don’t put the address on a list of where that sample came from; we’ll just put a number on the well and note that they’re all in this area so that we can say within this area of 200-300 wells, we’ve tested this many, and this many had these contaminants, but it doesn’t identify which individual well – it’s more of an area,” said Ms. Ruiz. “People are concerned about the value of their home. … So we do struggle with getting information from folks and getting folks willing to volunteer their well information, but the best way is not to identify exactly where the location of the well is. Do it more in a cluster.”

QUESTION: What is the role of the California Water Board has regarding the vast amounts of domestic wells in use in the state?

“The Water Board doesn’t regulate individual domestic wells, but Water Board is providing resources through different venues, like through us, CV-SALTS, and other places to get testing,” said Ms. Ruiz. “Some counties do more than other counties do to help get information out to folks. And the GSAs, partially funded a little bit and some of the efforts funded by the state, are trying to get information available on websites for people to find out what’s going on in their area. But nobody’s regulating domestic wells.”

QUESTION: California legislation and proposed water-saving measures, will the 40 million people living in California be able to comfortably live here for the next three to four decades?

“Define comfortably,” said Sue Ruiz. “One of the reasons that domestic well users might not want to connect is that they don’t want to be metered and told how much can and can’t use. However, what I’ve seen is that the ones who really don’t care are maybe 1% or 2%. Most of the domestic well users (not all, but the ones that we work with anyway) are conscientious about needing to reduce their water use, especially in their yards. So it becomes a little less comfortable when you can’t just use as much water as you want to. Obviously, why we buy things is because of marketing, so we have to market to use less water and just use really good marketing strategies for people to make the decisions about their water use, and that will help at least.”

“I think it depends on what kind of water use the question asker is talking about,” said Amanda Monaco. “If we’re referring to simply drinking water, we have enough water to serve drinking water needs, although maybe not in Southern California. That’s a problem, given how dependent they are on interconnected surface water and climate change, which might make those surface water supplies less reliable. So that’s going to be concerning, but at least in the Central Valley, there is enough water for everyone to use and definitely in Northern California.”

“It is how we are using that water that is the problem the way we see it,” continued Ms. Monaco. “So for just drinking water, there is enough. We also have all these other industrial actors who are using 70% of the water, and that is why the groundwater levels going declining. That’s why we’re seeing this need to do recharge. So I think if we can do recharge, and if we can also just reevaluate the way that we’re using water and potentially have a smaller agricultural footprint, then I think that would help make sure that we have water to last for decades and decades and decades.”

QUESTION: Looking forward, what recommendations do you have for residents with wells in small communities in Northern California, knowing that crops like marijuana are very thirsty and maybe popping up here and there and everywhere? Is there a grander plan to connect disparate water systems to provide more resilience and backup?

“In terms of connecting, it’s expensive, and it’s a long process if you’re going to use state funds, which of course are limited, to do connections to a larger public water system,” said Ms. Ruiz. “Fresno, which I can speak about the best, has brought in surface water when it’s available, and now they have a surface water treatment plant. They got money from the state back in the day when they were incentivized to do so, and that’s how we got these communities and a school in the communities funded to connect to Fresno. It’s a very long process that takes a lot of cooperation, a lot of trust building, and a lot of talking. And I will say that the larger communities and cities are not always willing to take on customers; one reason is they don’t have the staffing to go through the whole process.”

“Here in Fresno, that’s changing,” continued Ms. Ruiz. “Fresno stepped up. We’re working with Fresno State, and they came up with the study. We’re going to be consolidating 12 independent water systems and then two or three communities to the city because they stepped up and said, ‘let’s just make this happen.’ So I think it’s shifting a little bit to let these folks get connected. But it’s hard.”

Ms. Monaco recalled that someone from Lake County said they had done a lot of consolidations and connected a number of different systems. “So it’s possible, and there’s precedent for it. So I would say, you should definitely look into it … An academic institution was key in our area to look into doing those feasibility studies and seeing if that was possible. So I would suggest reaching out to Humboldt or someone up there to see if they could help with that analysis. I’m not sure who’s managing groundwater up there, but I would hope they would be looking out for, seeing this growing industry and planning to have some sort of warning system if it starts using too much water.”

QUESTION: The examples that Sue Ruiz gave seemed all positive regarding water quality for drinking water wells. And are there other examples that are negative? Do you know of any places where it’s negatively impacted drinking water?

“Not yet,” said Sue Ruiz. “But I do know there are plumes up gradient from Easton, where that ponding basin went in. So when we get really wet years, and the water flows there, maybe we will know that some of those plumes have moved into the community that weren’t there before … I don’t think there’s been enough opportunities or examples, and I don’t think there’s been enough study to answer that question. We just happened to notice the two that I talked about that were positive – there were two dots, and we put them together. And now, let’s look for this on purpose, intentionally. But I’m not aware of any negative impacts that have been examples. I think there’s potential for negative, so it has to be watched. The GSAs are charged with that. GSAs are supposed to make sure that negative impacts don’t happen, but how they’re going to go about doing that is still to be determined by each GSA. Some are a little bit more adaptable and willing than others. So we’ll see how it goes over the next 5, 10, and 20 years.”

Ms. Monaco said, “When we were first hearing about the potential of recharge basins to be made over land that was previously used for agriculture, or hearing about GSA and landowners having these ideas to do on-farm recharge … we know that there’s a ton of contamination from pesticides and fertilizers and other agricultural applied chemicals in the soil where these basins might be located, or where the on-farm recharge might be done. So it would eventually have gotten into the drinking water of folks that we work with maybe in 40 years. But having a recharge project there now makes that all of that contamination wash through and come directly into the drinking water within the next couple years.”

“First of all, residents that we work with really want to make sure that we prioritize non-on-farm recharge, that we prioritize recharge that is done on land that has not been previously used for agriculture, and could have a lot of other benefits like wetlands restoration or floodplain restoration,” continued Ms. Monaco. “Recharge could be done in areas that both have ecological benefits and don’t have historical agricultural contamination. And if you’re going to do on-farm recharge or locate a recharge basin over land that has had agriculture on it for a long time, you need to take soil samples; you need to see what the potential impacts will be and be monitoring that closely. And when those contaminants inevitably get into a nearby drinking water supply, whoever did that recharge project needs to be responsible for making sure that they have an alternative source of water or that there is a treatment for any nitrates or other contaminants that are entering their water.”

“In terms of individual domestic well users, because you own your own, well, it’s up to you to figure out what to do, how deep to go,” said Sue Ruiz. “There are some minimum county-driven public health requirements. But since the water is so much further, or the contaminants are up here where there isn’t any water, how long will it take to get down? Do I go ahead and drill down to 300 feet or 400 feet or spend the money on that? How deep do I make my seal? Is this sufficient? Okay, I’m not required to go this deep, but is it worth it to me to spend X number of dollars more to make that seal deeper? Those are all hard questions even to know to ask, and then to get answers to.”

“Somehow, we have to get this information out to people so that they can make well-informed decisions about their long-term water supply and the value of their homes,” continued Ms. Ruiz. “If I’m going to sell my house in 20, 30, or 50 years, and I need to make sure I have water; otherwise, it’s not going to be worth anything. And I need to drill my well during the wet time when the drillers are less expensive and aren’t so busy. Thinking ahead like that is hard. But that’s part of what we need to do is to help people get that information so that they can make those decisions.”

“Something that we learned while creating these water quality documents is that a lot of people are having to balance the decision of my wells going to go dry, or I can have some water, but that water might be carrying other things with it,” said Taylor Broadhead. “So I think getting as much data as we can that’s more openly available so that we can have better support and making decisions on where we can do recharge and what the impacts might be. If we do recharge there, how much water do we need to put on to where we can dilute it so that if we do bring a rush of contaminants toward a drinking water well, how quickly and how much will we need to be able to clean that up?”

“I think on-farm recharge does pose an additional risk because there have been contaminants and nutrients and pesticides applied to that land previously,” continued Ms. Broadhead. “Something we also learned through these water quality documents is that there are also lands that definitely could be a no – for example, recharging on dairies on what used to be a dairy lagoon. So just getting that information out and making it available – there’s a lot of work to do.”

QUESTION: What are your recommendations for local agencies such as GSAs or state agencies to listen to and address the needs of community members?

“We have to get them to listen and then put money behind it,” said Ms. Ruiz. “And where does that money come from?”

“Historically on drinking water issues, we’ve found some alignment with the State Water Board, and there’s been some encouraging legislation that we’ve helped pass to give them more powers,” said Amanda Monaco. “But they’ve been more aligned on making sure they understand the need for safe, reliable, and affordable drinking water. And I think the SAFER program has been great in that we’re actually finally addressing some of these affordability issues. The State Water Board’s SB 88 power where they can force a water system to connect to a community water system that is suffering; that’s been really powerful and has opened up a whole new area of work, where they can facilitate that process and make sure that happens.”

“But there are still really big concerns about water affordability,” Ms. Monaco continued. “We still have a lot of unsolved issues around water affordability. And then on the water resource management side, we have CV-SALTS, at least in the Central Valley; we have this process where local agencies are starting to look at nitrate contamination and how to remediate it and prevent more contamination. And that needs to be done 1000-fold for all contaminants. Then on the groundwater management side, we need a lot of better commitment from groundwater sustainability agencies on the ground and the Department of Water Resources at the state level to make sure that we’re managing our groundwater in a way that protects community drinking water.”

Sue Ruiz said we have to give credit to SGMA and the GSAs. “The SGMA Act was just passed in 2014; that was only seven years ago. From conception to saying this is what’s going to happen to where we are today, from the ground up, it’s never been done like this before – where the authority was placed at the local levels, all the locals had to get together, and all have to get in the sandbox and play nice … “Truly, it has come together relatively quickly. We have come a very long way, really in a short time.”

Ms. Ruiz also pointed out that she’s been involved in this work for almost ten years. “When I first started, the state was thinking about incentives for disadvantaged community funding, and now there is this much money set aside, you get an incentive, you get bonuses, if you help. So there’s been a shift at the state level too, so we have to give credit to those two things and recognize that there has been a lot of work done.”

“Yes, we have a lot of work to do, but we’ve come a long way in a very short period of time,” said Ms. Monaco.