At the January meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, Delta Watermaster Michael George updated the Council on curtailment and reporting orders in the Delta, the implementation of the Delta Alternative Compliance Plan for measuring diversions in the Delta; a pilot program for water conservation and quality protection in the Delta; building capacity within the Delta; and a status update on water quality control planning for the Delta watershed.

Update on Curtailment/Reporting Orders in the Delta

In 2021, the State Water Resources Control Board Division of Water Rights accelerated the work on developing a methodology to better manage the complex water rights system throughout the entire Delta watershed.

In 2021, the State Water Resources Control Board Division of Water Rights accelerated the work on developing a methodology to better manage the complex water rights system throughout the entire Delta watershed.

“Of course, it was a priority, but there are a lot of the intricacies of different areas of the watershed, tributaries, physical and governance factors that require a very sophisticated methodology to figure out how to manage this complex water system,” said Mr. George.

The Water Board adopted emergency regulations in August. Under those emergency regulations, both the Office of Delta Watermaster and the Division of Water Rights collaborated on issuing curtailment orders and reporting orders; the refinement of that methodology is ongoing. Although the new methodology was applied for the first time with those regulations and the orders that came out of them, the Water Board staff has focused on improving the quality of the data.

“On the one hand, improving the methodology is a great step forward, but if you’re still using data that are not reliable, not consistent, or not timely, you have this garbage in, garbage out problem,” said Mr. George. “The methodology works well, but data going into it needs and has needed to be updated. So we focused additional effort on improving the data that goes into the methodology, not just for curtailment purposes, but for understanding and managing how water is used in the Delta and how it interacts with invasives, temperature, and exports and with the quality of the environment.”

So far this water year, two atmospheric river events in October and December were followed by a very dry January. However, this methodology allows the Division of Water Rights to take into account real-time or close to real-time information, and alert users in those tributaries of the shortage and how much cutback through the priority system needs to be implemented.

“We saw the Division of Water Rights completely lift curtailment in light of the increase in precipitation, and then just recently began to reinstitute some of those curtailments in some of the Delta tributaries,” he said.

He noted that on the week of the 18th of January, curtailments were reimposed in Putah Creek at a relatively junior priority of 1986 and in the Fresno River with a priority of 1959. Due to continuing dry conditions, Cache Creek was recently added at a priority of 1946, and Putah Creek priority went from 1986 to 1945. The Chowchilla River was added to the list with a priority date of 1959, and for the Fresno River, the priority date, which had been 1959, was pushed back to 1873.

“Those fairly acute impacts of the methodology, improved data from water users, and improved data from the drought forecasting capabilities both through the Department of Water Resources and NOAA, allows us to make much more acute curtailment decisions,” said Mr. George.

Mr. George noted that making those decisions requires communicating them. One of the emergency regulation components was that the Water Board now has the authority to communicate with water users electronically. Water users are now required to check the website and can subscribe to email lists for updates.

“All of this prepares us for how we will manage if the drought persists,” he said. “When I say ‘we,’ I mean the entire water community, not the just the Water Board, not just the export interests, not just the ag or urban water users, but that whole community to share the same information and to have much more predictability about what can happen and how these various constituencies can plan to respond.”

Implementation of the Delta Alternative Compliance Plan

The Delta Alternative Compliance Plan is currently in effect.

The Delta Alternative Compliance Plan is currently in effect.

In 2015 during the latter part of the last drought, the legislature passed a law requiring better monitoring and measurement of diversions throughout the state. The Water Board adopted regulations to implement the legislation in 2016. However, there were many unforeseen challenges with measuring diversions in the Delta, so rather than put a meter on every siphon and pump in the Delta, an alternative plan for compliance was developed that uses satellite imagery to give more consistent, timely, and credible information on water use.

Open ET monitors evapotranspiration at the field level in the Delta and can compare it to other periods, other crops, or different conditions within the Delta. Mr. George noted that the information is available weekly or even sub-weekly, so instead of waiting for annual water use reports, it can now be tracked on a close to real-time basis through Open ET.

“The Alternative Compliance Plan uses Open ET and creates a software bridge between that very powerful new tool to estimate consumptive use within the Delta and links it to the Water Board legacy report management system,” he said. “That bridge allows individual water users to input their information literally down to their field level, and allows the software to reach the information previously stored in the report management system at the board, and then query Open ET to respond with how much water is being used in that very specific area of place of use. So it can tell us how much water is being used on a close to real-time basis.”

The first reports filed under the Alternative Plan of Compliance filed by water users will be in February of 2023, but currently, they can access Open ET to understand what is happening on a real-time basis.

“We’re learning more about how to help all water users be more strategic about how and when they access that shared precious water resource,” he said.

Pilot Program for Water Conservation and Quality Protection in the Delta

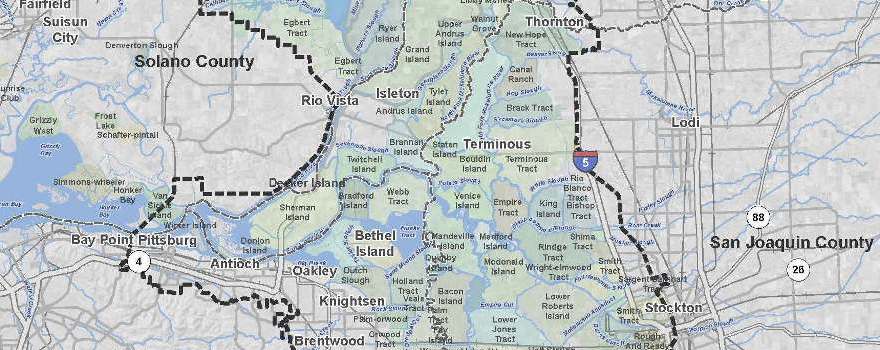

Work is underway in the Delta to plan for a response to recurring hot droughts. Mr. George noted that the Delta does not experience drought the same way drought is experienced throughout the rest of the state. It’s not experienced in the Delta as a reduction in the amount of available water, but due to its connection to the upstream watersheds, the Bay, and ultimately the Pacific Ocean, it’s a risk to water quality. Additionally, the water quality risk and drought conditions are different in the different parts of the Delta.

Work is underway in the Delta to plan for a response to recurring hot droughts. Mr. George noted that the Delta does not experience drought the same way drought is experienced throughout the rest of the state. It’s not experienced in the Delta as a reduction in the amount of available water, but due to its connection to the upstream watersheds, the Bay, and ultimately the Pacific Ocean, it’s a risk to water quality. Additionally, the water quality risk and drought conditions are different in the different parts of the Delta.

Recognizing this, the three Delta water agencies have come together to present a unified voice for the Delta that recognizes the differences in the different parts of the Delta. They initiated a collaboration with the state agencies that have responsibility for management or regulation of water use in the Delta, including the Department of Water Resources, the California Environmental Protection Agency, the Office of the Delta Watermaster, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the Department of Food and Agriculture.

“We recognized that taking effective action in the Delta when drought happens depends on planning ahead of time, and not emergency response,” said Mr. George. “So the idea was to develop a grant program for the current water year, so we developed a collaborative approach to piloting experiments and actions that could be taken in the Delta that would both conserve water and also protect water quality.”

The state agencies then entered into an interagency agreement to empower the Delta Conservancy to manage this program, which launched on the 18th of January.

“It challenges water users in the Delta to propose actions that they think would have positive effects in managing during a drought, primarily to manage the extent of consumptive use by crops and to protect the Delta from salinity intrusion,” said Mr. George. “Importantly, the Delta water agencies and the state agencies agreed that these efforts should be for the benefit of the Delta, rather than for the benefit of anybody else, whether it’s exports or even water users in the Delta. The idea was that this should help the environment of the Delta. This should be on top of other regulatory approaches to protect Delta water quality and the ecosystem.”

“It’s not about fallowing; it’s not about stopping agriculture,” he continued. “In fact, one of the things that we’re saying is that we don’t want bare ground out there. Even if we’re going to try and reduce water use by going to a less intensive crop, we want to have a cover crop, or at least leave stubble there. Because we know that the health of Delta soils depends on keeping roots in the soil. In addition, we want to make sure that we know what kind of crop rotations provide the most benefit. So that’s why we started this program by asking farmers to propose to us what they thought would be the best activities to further these objectives, data, and understanding.”

They have already received over 30 applications for the program. Ultimately, they will begin making grants on a rolling basis and create a mechanism using open ET and augmented with a ground-truthing program managed under a contract between the Department of Water Resources and the University of California Davis.

“We hope through this process to learn a lot more about how these agencies in the Delta and the State agencies can learn from this process together and have credible data that they can both rely on in developing programs that will be more predictable, in terms of response for future or persistent droughts,” he said.

Building Capacity within the Delta

Building on that momentum toward improved communication, collaboration, and shared data streams, the Office of the Delta Watermaster, along with many other collaborators, is working consciously to develop greater capacity within the Delta.

Building on that momentum toward improved communication, collaboration, and shared data streams, the Office of the Delta Watermaster, along with many other collaborators, is working consciously to develop greater capacity within the Delta.

“The idea is to connect responsible voices in the Delta to work out priorities among themselves and to work with state agencies of various kinds – the Office of the Delta Watermaster, the Delta Stewardship Council, the Division of Water Rights at the Water Board, the Department of Water Resources, the Delta Conservancy, the Delta Protection Commission. All these state agencies that have been created to help inform the state about management in the Delta will now work to develop a partner that can engage more effectively. Because, as we’ve all experienced over time, it is hard to engage with the Delta communities, which are busy doing their own things, and often have differences of impact for priorities among them.”

The pilot program is an opportunity to develop the capacity in the Delta to write grant proposals, administer grants, and comply with the requirements of those grants,

“There’s a lot of money out there, but the Delta has never been effective in competing for that money to do multi-benefit projects within the Delta,” said Mr. George.

Status of water quality control plan update

Lastly, Mr. George gave an update on the status of the Water Board’s Water Quality Control Plan process for the Delta. In 2018, the State Water Board adopted a revision to the water quality control plan for the portion of the Delta watershed on the San Joaquin side and salinity objectives in the southern Delta. At that time, voluntary agreements were proposed to be developed that would be used to implement that water quality control plan instead of the Water Board’s full natural flow approach to increasing flows in the Delta.

Lastly, Mr. George gave an update on the status of the Water Board’s Water Quality Control Plan process for the Delta. In 2018, the State Water Board adopted a revision to the water quality control plan for the portion of the Delta watershed on the San Joaquin side and salinity objectives in the southern Delta. At that time, voluntary agreements were proposed to be developed that would be used to implement that water quality control plan instead of the Water Board’s full natural flow approach to increasing flows in the Delta.

Negotiations over options for implementing the State Water Board’s regime ensued; however, in October, the Secretaries of the Department of Natural Resources, Department of Food and Agriculture, and Cal EPA all decided that the voluntary agreement process had not developed traction in the San Joaquin part of the watershed. So in December, the Water Board instructed staff to focus on implementing the Water Quality Control Plan as adopted, leaving room for voluntary agreements if they should happen.

The State Water Board is pursuing the implementation through a program of water rights administration, potentially adjudication or individual waterways decisions, or potentially through a regulatory action that would have a broader impact.

Mr. George said that in the spring of 2022, drafts will be released for the San Joaquin and the Sacramento River with opportunities for public comment periods, testing the science and insight, and proposing alternatives to further inform the board. So those processes are moving forward and are likely to result in final proposals being presented for board consideration sometime in the early fall of 2022.

The Water Board’s efforts will be informed by ongoing processes such as the Delta Adapts project and the upcoming series of salinity workshops being organized by the Delta Science Program. He also expressed appreciation for Dr. Conrad’s presentation to the Collaborative Science Adaptive Management Program on the review of Delta’s existing environmental review programs and how they could be improved.

Discussion period

During the discussion period, Chair Susan Tatayon asked if Council members and the general public can access the Open ET portal or website and see the progress or data. Is it open to the public?

Mr. George said absolutely; the data is accessible to anyone at OpenET.org. “There’s a mapping function that can get you down to the field level. So if you’re a farmer in the Delta, and you want to know how much water you will apply next week, you need to know how much water your field consumed and used to grow the crop last week. Irrigation essentially replaces the water that the plant has used so that there’s available water to use going forward. So yes, it’s accessible.”

Mr. George also noted that the pilot program for Delta drought response relies on Open ET to measure the effect of the proposed actions; this couldn’t have happened if not for the Alternative Compliance Plan. “Because that was Delta water user-led, they helped pay for it. They were technical advisors on it. And over five years, there was developed a lot of credibility and understanding of why Open ET made sense and how it could be used to develop very rigorous processes of demonstrating the accuracy of this new science that was being developed and captured in that tool.”

“This stuff is cumulative,” he continued. “The Delta is wickedly complex. We have a series of aha moments that inform incremental improvements in how we manage and how we manage depends importantly on bringing all the constituents along on a regular basis.”

Vice Chair Virginia Madueño asked how he is engaging with Delta farmers. Do you have a developed list already of key stakeholders, in this case, farmers that you already work with? And are there any other strategies you’re implementing to ensure you include as many farmers as possible in the process?

“One of the challenges is you never know how well the outreach is going until you see the applications come in,” said Mr. George. “The most effective first line of communication is through the three Delta water agencies: the North Delta Water Agency, which are Yolo, Solano, and Sacramento Counties; and the Central and South Delta Water Agencies, which are Alameda and San Joaquin counties. Each of those agencies has an elected board, and each of those agencies assesses all the acreage in their area. So there’s a pretty tight connection between farmers and their representatives on those boards. In addition, every island has a Reclamation District that is essentially the way farmers within that island cooperate to maintain and manage their levee protections. And there are the county farm bureaus. But the water agency boards; there are 15 farmers elected by their constituents, and they’re extremely well connected in their farming communities. And they’ve been the most effective at getting this word out.”

“Going beyond that, there are other communities of interest, whether they’re farmworkers who don’t own land or their tenant farmers who work with the landowners, or whether it is people like the Metropolitan Water District that manage four critically important located islands in the Delta. So you’re quite right; it takes a lot of outreach to a lot of different constituencies. So I’ve been pleased to work with Dr. Rudnick on some of the outreach for community engagement and identifying landowners who can help to inform some of the adaptation strategies and so forth. So it’s, it’s a complex place, and it’s a multi-pronged approach to maintaining or gaining connection and credibility with all those communities.”