Within the Central Valley, over seven million acres is in irrigated agriculture, and depending on the conditions, water discharged from the site may carry nutrients, pesticides, and pathogens off-site and into water bodies or aquifers. The Central Valley Water Board’s Irrigated Lands Regulatory Program (ILRP) addresses these discharges that can harm aquatic life and make the water unusable for drinking water or agricultural uses. The goal of the ILRP is to protect surface water and groundwater and reduce the impacts of irrigated agricultural discharges to surface water and groundwater.

At the October 5 meeting of the State Water Resources Control Board, Sue McConnell, manager of the Central Valley Water board’s Irrigated Lands Regulatory Program, updated the board members on the Eastern San Joaquin program, covering program milestones, the status of on-farm drinking water well monitoring efforts, completion of the San Joaquin surface water monitoring framework and external review, development of additional groundwater protection measures, and anonymous field level reporting.

Background on the Irrigated Lands Regulatory Program

Anyone who irrigates land to produce crops or pasture commercially within the Central Valley must seek permit coverage under the program. There are two pathways to comply:

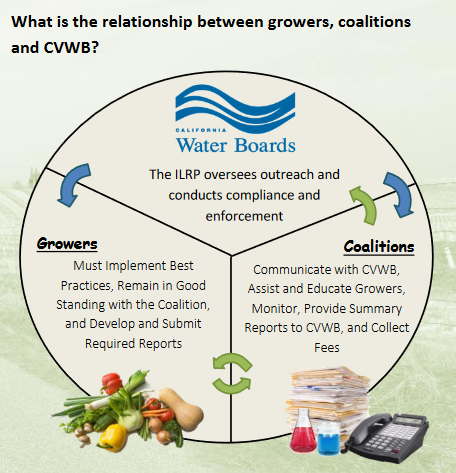

- Growers can join a coalition and then comply with the WDRs by implementing management practices that are protective of water quality and preparing plans and reports on their practices. The coalition groups work directly with their member growers to assist in complying with Central Valley Water Board requirements by conducting surface water monitoring and preparing regional plans to address water quality problems.

- A grower may seek individual coverage by submitting a Notice of Intent and paying the fees directly to the Central Valley Water Board. In this case, the grower would communicate directly with the Central Valley Water Board and bear the full cost and responsibility for compliance, monitoring, and reporting.

The goal for the Irrigated Lands Regulatory Program is to ensure that discharges from commercial irrigated lands do not impact beneficial uses. The Central Valley contains about 75% of the state’s agricultural land; activities on those lands are regulated using nine general waste discharge requirements or WDRs. Growers are assisted by 14 agricultural coalitions.

The goal for the Irrigated Lands Regulatory Program is to ensure that discharges from commercial irrigated lands do not impact beneficial uses. The Central Valley contains about 75% of the state’s agricultural land; activities on those lands are regulated using nine general waste discharge requirements or WDRs. Growers are assisted by 14 agricultural coalitions.

The Board is developing seven geographic and one commodity-specific general waste discharge requirements (WDRs) within the Central Valley region for those that are part of a coalition and one for those who are not part of a coalition. The geographic/commodity-based WDRs will allow for implementation requirements based on the specific conditions within each geographic area; consistency between the WDRs will be maintained through the use of templates for plans, evaluations, drinking water notices, and reports.

The program will focus on high vulnerability areas and areas with known water quality issues. The Eastern San Joaquin River Watershed General Order was the first of these orders to be considered by the Board.

General WDRs are primarily geographically based. There are seven geographic and one commodity-specific general WDRs for growers participating in coalitions.

General WDRs are primarily geographically based. There are seven geographic and one commodity-specific general WDRs for growers participating in coalitions.

The California Rice Commission is the one commodity-specific coalition, shown in red on the map. Rice was exempted from the petition order’s nitrogen groundwater protection requirements because rice operations have unique practices that minimize the potential to discharge nitrogen.

There’s also a general WDR for growers who are regulated individually, but no grower is currently choosing that option.

There is one coalition per coalition-based WDR, except for the Tulare Lake basin, shown in light blue, which has seven coalitions. The coalition-based WDRs contain requirements for the coalition and their growing members.

The coalitions represent the growers and assist their members by informing them what their requirements are and letting them know what they need to do to comply. The coalitions act as intermediaries between the growers and the Water Board; however, the coalitions do not enforce the WDRs or monitor individual member discharges. Instead, the coalitions are responsible for fulfilling regional requirements and addressing water quality issues by monitoring water quality and working with growers to implement practices according to management plans. Coalitions must meet the requirements of the WDRs and provide the information needed by the Central Valley Water Board to assess grower compliance.

The coalitions represent the growers and assist their members by informing them what their requirements are and letting them know what they need to do to comply. The coalitions act as intermediaries between the growers and the Water Board; however, the coalitions do not enforce the WDRs or monitor individual member discharges. Instead, the coalitions are responsible for fulfilling regional requirements and addressing water quality issues by monitoring water quality and working with growers to implement practices according to management plans. Coalitions must meet the requirements of the WDRs and provide the information needed by the Central Valley Water Board to assess grower compliance.

Implementing the Eastern San Joaquin petition order

The Eastern San Joaquin Coalition has about 700,000 irrigated acres and 3100 members. The coalition received the first adopted irrigated lands general WDRs, which were petitioned to and adopted by the State Water Board. The petition order updated the San Joaquin general WDRs and included requirements for the Central Valley Irrigated Lands Program and irrigated lands programs statewide.

On February 7, 2018, the State Water Board adopted Order WQ 2018-0002 in response to the petitions of the Eastern San Joaquin River Watershed General Waste Discharge Requirements, the first requirements adopted by the Central Valley Water Board to address discharges of waste from irrigated lands to both surface water and groundwater.

In October of 2018, the Central Valley Water Board’s executive officer approved three templates required by the petition order after they were publicly noticed and comments addressed: The Irrigation Nitrogen Management Plan template and summary report template, and the drinking water notification template.

The drinking water notification template was developed in close collaboration with representatives from the environmental justice organizations, the Division of Drinking Water, and agricultural coalitions to meet the petition order requirements. This template is sent to coalition members with an information packet before initiating the monitoring requirements; it is available on the Irrigated Lands Program website in English, Spanish, Punjabi, and Hmong.

The drinking water notification template was developed in close collaboration with representatives from the environmental justice organizations, the Division of Drinking Water, and agricultural coalitions to meet the petition order requirements. This template is sent to coalition members with an information packet before initiating the monitoring requirements; it is available on the Irrigated Lands Program website in English, Spanish, Punjabi, and Hmong.

“Coalition members with drinking water wells that exceed the nitrates drinking water standard must provide the template to users to inform them of the nitrate concentration and the dangers of consuming that water,” said Ms. McConnell. “They also have to provide a copy of it to the Central Valley Water Board to document that users were informed. Notification compliance is a very high priority for the program.”

The petition order requires East San Joaquin Coalition members to start monitoring on-farm drinking water wells annually in 2019. The Central Valley Water Board then prioritized the monitoring timelines for other coalitions based on groundwater nitrate concentrations.

The petition order requires East San Joaquin Coalition members to start monitoring on-farm drinking water wells annually in 2019. The Central Valley Water Board then prioritized the monitoring timelines for other coalitions based on groundwater nitrate concentrations.

Last year, members of the seven Tulare Lake Basin coalition started monitoring their drinking water wells annually. This year, members of three additional coalitions start monitoring their drinking water wells, and next year, members of the last coalition will start monitoring their drinking water wells; this requirement will cover all growers enrolled in the program.

Information on the Irrigated Lands Program drinking water well monitoring efforts is available on the website and includes information on the sampling requirements, lab information, the forms, and frequently asked questions.

The drinking water well data is available on GeoTracker. Just the nitrate concentration and sample data are available; grower information is not shown.

The table on the slide shows the monitoring data as of last month. Almost 7900 wells have been sampled, and in a few months, there will be grower-reported data on the number of active drinking water wells on grower parcels, and it will be possible to know the percent of drinking water wells that have been sampled.

The table on the slide shows the monitoring data as of last month. Almost 7900 wells have been sampled, and in a few months, there will be grower-reported data on the number of active drinking water wells on grower parcels, and it will be possible to know the percent of drinking water wells that have been sampled.

“Like last year, about 31% of the wells sampled did exceed the nitrate drinking water standards,” said Ms. McConnell. “But I’m happy to say that we have received over 99% of the required notifications.”

In February 2019, the Central Valley Water Board updated all coalition-based WDRs to include the petition order requirements. In March of that year, the East San Joaquin coalition members started preparing INMP. Members subject to water quality management plans also worked with the coalition to prepare management practice implementation reports or MPIRs, another new template required by the petition order.

In July 2019, our executive officer approved the methodology proposed by the San Joaquin coalition to identify nitrogen deficiency outliers; this identification can trigger additional certification, outreach, and management practice requirements.

External review

In August of 2019, the Central Valley Water Board contracted with the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project to facilitate an external expert review of the East San Joaquin surface water monitoring framework to answer specific questions about the East San Joaquin surface water monitoring framework. These questions included whether the representative monitoring approach is appropriate for regulating irrigation operations, whether the framework has sufficient density to reasonably identify exceedances throughout the watershed, and whether the framework provides adequate feedback between management practices implemented and water quality goals.

In August of 2019, the Central Valley Water Board contracted with the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project to facilitate an external expert review of the East San Joaquin surface water monitoring framework to answer specific questions about the East San Joaquin surface water monitoring framework. These questions included whether the representative monitoring approach is appropriate for regulating irrigation operations, whether the framework has sufficient density to reasonably identify exceedances throughout the watershed, and whether the framework provides adequate feedback between management practices implemented and water quality goals.

A nine-member stakeholder advisory group with three environmental, three agricultural, and three Water Board representatives then selected the five-member panel with expertise specified by the petition order. Last year, the panel held multiple meetings that included a field trip to the East San Joaquin Coalition’s monitoring locations. Before releasing the draft and then final recommendations, there was ample opportunity for public input.

All of the meetings, presentations, public comments, and the final report are available on this page: www.sccwrp.org/about/research-areas/additional-research-areas/east-san-joaquin-expert-panel

The panel brought their final report to the Central Valley Water Board earlier this year.

The panel brought their final report to the Central Valley Water Board earlier this year.

“The good news is that they found the program generally adequate and appropriate to achieve our overarching goals,” said Ms. McConnell. “They endorsed the program’s overall monitoring design, the data collection and analysis methods, the adaptive nature of the program, and the use of data to inform management practices. They also included recommendations for improvement, which staff is evaluating.”

Reporting

Last March, the San Joaquin coalition members submitted INMP summary reports for the first time. Then last July, the East San Joaquin Coalition used that information to submit field-level data by anonymous member ID for the first time. The coalitions subject to the requirement jointly submitted a proposed groundwater protection formula work plan during that same month.

Last September, Central Valley Water Board staff provided the first annual report on the implementation of that petition order and will be reporting every fall as required. Staff will discuss whether anonymous field-level reporting is sufficient for program oversight and determining progress next year.

Last September, Central Valley Water Board staff provided the first annual report on the implementation of that petition order and will be reporting every fall as required. Staff will discuss whether anonymous field-level reporting is sufficient for program oversight and determining progress next year.

This spring, farm evaluations were due for all coalition members with the reporting frequency of every five years. Nitrogen removal coefficients were required for crops covering 95% of irrigated land acreage, and INMP summary reports for all coalition members were due for the first time.

All coalition-based WDRs have been updated to include the CV-SALTS requirements and to make them enforceable.

“Since the coalitions have been actively involved in the development of the CV-SALTs basin plan amendment, they knew this was coming,” said Ms. McConnell. “And they’ve been working very hard to keep their members in compliance.”

In July, the groundwater protection values were provided for high vulnerability townships.

Groundwater Protection Formula

The petition order requires the development of a groundwater protection formula to calculate values and targets for high vulnerability townships.

The petition order requires the development of a groundwater protection formula to calculate values and targets for high vulnerability townships.

The coalitions use the soil and water assessment tool to calibrate it for the Central Valley in conjunction with grower-reported data to estimate the current nitrogen loading. The soil and water assessment tool is a public domain model used to quantify the impact of management practices in large, complex watersheds. It can account for weather, land use, soils, crop growth, irrigation, nutrient loading, and other factors.

Last year, the proposed formula was released for public comment and discussed at the Central Valley Water board’s October board meeting. Staff met with the coalitions and environmental justice representative to discuss the comments, and the executive officer conditionally approved the formula in January of this year.

The values were calculated using the approved groundwater protection formula and represent the estimated nitrogen loading due to current farming practices. Groundwater protection values are township-based and were provided six months after executive officer approval as required. The proposed values were released for public review discussed at the July irrigated lands stakeholder meeting and were the subject of an information item at the October Central Valley Water Board meeting.

Calculating groundwater protection values

The purpose of the Groundwater Protection Formula is to “generate a value (the Groundwater Protection Value or GWP Value), expressed as either a nitrogen loading number or a concentration of nitrate in water (such as mg/l) as appropriate, reflecting the total applied nitrogen, total removed nitrogen, recharge conditions, and other relevant and scientifically supported variables that influence the potential average concentration of nitrate in water expected to reach groundwater in a given township over a given time period.” (Order WQ-2018-0002)

The purpose of the Groundwater Protection Formula is to “generate a value (the Groundwater Protection Value or GWP Value), expressed as either a nitrogen loading number or a concentration of nitrate in water (such as mg/l) as appropriate, reflecting the total applied nitrogen, total removed nitrogen, recharge conditions, and other relevant and scientifically supported variables that influence the potential average concentration of nitrate in water expected to reach groundwater in a given township over a given time period.” (Order WQ-2018-0002)

Ms. McConnell gave a high-level overview of the three steps involved in developing the groundwater protection values.

The first step is to compile the significant data needed by the Central Valley Soil and Water Assessment Tool. The second step uses that data to simulate crop growth and develop a root zone library. Currently, that library contains over 200 million unique crop, soil, and climate management zone scenarios with the corresponding percolation and nitrogen loading estimates, and those numbers are used in step three.

The third step is to compute the groundwater protection value. The graphic on the left side is an example township with different units and parcels outlined in black. Each parcel is evaluated individually. So, for example, there is a parcel in the township where processing tomatoes are grown on six different soil types. First, the grower data is matched to the result library scenario to estimate the nitrogen loading for each soil type. Then the six results are acre weighted to estimate the nitrogen loading for each parcel, which is aggregated with the other parcel values to calculate the groundwater protection value for the township.

Data collection

The collection and evaluation of nitrogen and management practice data are important components of the Irrigated Lands Program efforts to assess grower trends and performance. The data are used to identify protective practices and nitrogen deficiency outliers, develop groundwater protection targets, and estimate acceptable multi-year A/R ranges by crop.

“Given its importance, we continue to engage with Coalitions on improving the quality of this member-reported data,” said Ms. McConnell. “We’re also collaborating with university researchers on its use, as well as evaluation of its quality.”

Groundwater protection targets

Next summer, township-based groundwater protection targets must be developed for incorporation into Groundwater Quality Management Plans.

Next summer, township-based groundwater protection targets must be developed for incorporation into Groundwater Quality Management Plans.

Groundwater protection targets are township-based nitrogen loading rates needed to comply with receiving water limitations. This requires information on existing groundwater quality and a process for estimating the effects nitrogen loading has on groundwater. Targets will be released for public review and comments before executive officer approval. They will be reviewed every five years.

The Management Practice Evaluation Program, or MPEP, is an umbrella for evaluating practices.

“The petition order inserted the groundwater protection targets into the program to make the connection to groundwater quality,” said Ms. McConnell. “So on this slide, the water droplets represent the six MPEP goals. And the three dark droplets represent the questions that will be answered using groundwater protection values and targets.”

“The petition order inserted the groundwater protection targets into the program to make the connection to groundwater quality,” said Ms. McConnell. “So on this slide, the water droplets represent the six MPEP goals. And the three dark droplets represent the questions that will be answered using groundwater protection values and targets.”

There are three MPEP elements that are interconnected: the management practice assessment, the groundwater protection values and targets, and then the implementation of those management practices via the groundwater quality management plan.

“The assessment looked at both existing and new practices, and evaluating whether they’re protective or improving groundwater quality,” said Ms. McConnell. “But it’s the values in the targets that get at that connection to groundwater quality, getting at the loadings to groundwater, and then what do you need for compliance and meeting the groundwater receiving water limitations. And then finally, the implementation of those protective practices will happen through the groundwater quality management plan. And the timelines and the milestones will be included in that as well.”

“The assessment looked at both existing and new practices, and evaluating whether they’re protective or improving groundwater quality,” said Ms. McConnell. “But it’s the values in the targets that get at that connection to groundwater quality, getting at the loadings to groundwater, and then what do you need for compliance and meeting the groundwater receiving water limitations. And then finally, the implementation of those protective practices will happen through the groundwater quality management plan. And the timelines and the milestones will be included in that as well.”

DISCUSSION PERIOD

Board member Laurel Firestone asked about the domestic well testing. “Is there any data on how many are providing replacement water? Because it seems like what’s being submitted is a notice that they’ve notified people.”

Ms. McConnell noted that it’s not a requirement to report that, but it is included in the notification form. “Some members did provide that information, but it isn’t required; it’s voluntarily submitted. So we have some information, but it’s limited.”

Ms. Firestone asked about the current level of enrollment and the status of the reporting. Ms. McConnell said they continue to work on enrollment issues. They have done quite a bit of work, mapping out potential commercial irrigated lands operations to follow up on.

“We know that there are still operations out there that are not enrolled in the program,” said Ms. McConnell. “There’s still going to be a significant number of smaller operations which are not on the program, and we’re still continuing to following to follow up on that.”

“In terms of the reporting, we do actually have more compliance work to do with reporting because now we’re reaching out to low vulnerability areas who never submitted summary reports in the past. So we recognize there’s going to be more work for both the coalitions and us moving forward because of the requirements from the petition order.”

Patrick Palupa, Executive Officer of the Central Valley Water Board, acknowledged there’s still a significant amount of acreage not enrolled in the program comprised of small parcels. “We’re talking about thousands and thousands of parcels. The lion’s share of these parcels are less than 10 acres: 1 to 10 acres 45%; less than one acre 28%; so really, we’ve been able to kind of knock out all of the big guys; I think it’s just about everybody over 100 acres is in the program. I think it would be hard to find somebody who’s outside of the program who’s over 100 acres. But it’s those two numbers, 28% and 45% of the percentage of the 35,000 potentially unenrolled parcels that we’re trying to figure out what’s the strategy going to be.”

Board member Laurel Firestone said the part of the idea of the reporting requirements and the evaluation programs is to see outliers and follow up on those. Are outliers being addressed?

Board member Laurel Firestone said the part of the idea of the reporting requirements and the evaluation programs is to see outliers and follow up on those. Are outliers being addressed?

Ms. McConnell said that work is ongoing. “Even with a nitrogen management plan, reporting folks have been looking at outliers and coalitions have been working with their members with outreach to let those growers know when they’re outliers that they are using quite a bit more fertilizer than their peers, and working with them,” she said. “That’s all in their annual report; how many outliers they’ve identified and what they’re doing in terms of outreach.”

Vice-Chair DeDe D’Adamo echoed the concerns about outliers. “I know that I’ve seen a big change, but it’s anecdotal,” she said. “As I talk with growers and folks out in the field, they express an awareness and how they have changed their habits. I get a sense that there’s this sort of crowd correction going on, but it would sure be great … I would leave that up to you to get a better sense of, in the case of outliers, how often you’re having to step in versus the coalitions versus what’s just occurring naturally.”

During the public comment period, Jennifer Clary, California Director for Clean Water Action, said that given the time that the program has been in underway, she’d like to see some results. “I think something we really need to discuss is how to incorporate some numbers, some actual water quality benefits into these regular reports. … I think particularly having a little less transparency in the data reporting is something that we were willing to trade and exchange for a more rigorous program, and we still want to understand where things are happening and how that’s occurring. And I think another piece of that is the enforcement. So if we’re going in and talking to folks, are we doing any on farm enforcement? And if not, because of COVID? When does it resume? And what does it look like? … “So it’d be really, really useful if between DDW, and the regional board and the management zones, we could all talk to each other and figure out how this information should actually be used to provide to ensure that people are safe drinking water.”

Mr. Palupa said that drinking water is an important component of our program, but drinking water and enforcement is being done under CV-SALTS, and not necessarily under the ILRP program, citing the limited enforcement staff. He also noted that the numbers for drinking water well exceedances and notifications is reported in the Executive Officer’s report.

Vice-chair DeDe D’Adamo, “My takeaway is that you have to know how better tell the story and link up these regulatory sort of the alphabet soup of the different programs, and how that translates to something that folks on the ground can understand will benefit them or it has already benefited them.”