In 2018, the State Water Resources Control Board adopted an amendment to the Recycled Water Policy to promote recycled water use, setting a numeric goal to increase the use of recycled water to at least 2.5 million acre-feet per year by 2030. The amendment included the narrative goals to reuse all dry weather direct discharge to ocean waters, enclosed bays, estuaries, and coastal lagoons to the extent feasible; and maximize the use of recycled water in areas where groundwater supplies are threatened.

At the October 19 meeting of the State Water Board, Rebecca Greenwood, an engineering geologist with the Recycled Water Unit in the Desalination Unit within the Division of Water Quality, presented the summary of the results from the second year of the implementation of the annual volumetric reporting requirements for wastewater and recycled water facilities statewide.

In June 2019, the State Water Board Executive Director issued orders requiring wastewater treatment plants and recycled water producers to report volumetric data annually. The requirements included information for influent, or the water coming into the plant; production, which is what level that water is being treated to or processed to; effluent, or how much water is leaving the plant; and recycled water use, which can include categories such as groundwater recharge, or landscape irrigation.

In June 2019, the State Water Board Executive Director issued orders requiring wastewater treatment plants and recycled water producers to report volumetric data annually. The requirements included information for influent, or the water coming into the plant; production, which is what level that water is being treated to or processed to; effluent, or how much water is leaving the plant; and recycled water use, which can include categories such as groundwater recharge, or landscape irrigation.

The main difference between previous efforts and the volumetric reporting requirements are that the reporting is now required, and the requirements apply to both wastewater treatment plants and recycled water producers.

The first reports for 2019 were collected after granting an extension and conducting outreach efforts in June 2020. Staff reviewed and completed quality checks and published the 2019 data on the California open data portal. Since January, minor changes were made to the reporting module and additional outreach conducted. Even in these uncertain times, there was 94% compliance for 2020 reporting with no deadline extension. Ms. Greenwood credited part of that success to the continued coordination with WateReuse California and the California Association of Sanitation Agencies, who provided information about the requirements and resources to their members.

The first reports for 2019 were collected after granting an extension and conducting outreach efforts in June 2020. Staff reviewed and completed quality checks and published the 2019 data on the California open data portal. Since January, minor changes were made to the reporting module and additional outreach conducted. Even in these uncertain times, there was 94% compliance for 2020 reporting with no deadline extension. Ms. Greenwood credited part of that success to the continued coordination with WateReuse California and the California Association of Sanitation Agencies, who provided information about the requirements and resources to their members.

Ms. Greenwood noted that while there is the same number of reporting facilities in 2020, they’re not the same 710 that reported in 2019, which is purely a coincidence.

Working with the Office of Enforcement, notices of violations were issued to facilities that didn’t report either their 2019 or their 2020 reports. A few of those have been collected, and staff will continue to work with the Office of Enforcement to increase compliance.

Working with the Office of Enforcement, notices of violations were issued to facilities that didn’t report either their 2019 or their 2020 reports. A few of those have been collected, and staff will continue to work with the Office of Enforcement to increase compliance.

Of the 710 facilities that have reported, 429 facilities, shown in green, are classified as wastewater treatment plants; these facilities receive raw influent wastewater, treat it to a standard and then discharge the effluent. 261 facilities, shown in dark blue, produce recycled water in compliance with Title 22. The remaining 20 facilities are recycled water producers that do not receive influent but instead receive treated wastewater from an upstream wastewater treatment plant and then treat it further to produce water in compliance with Title 22.

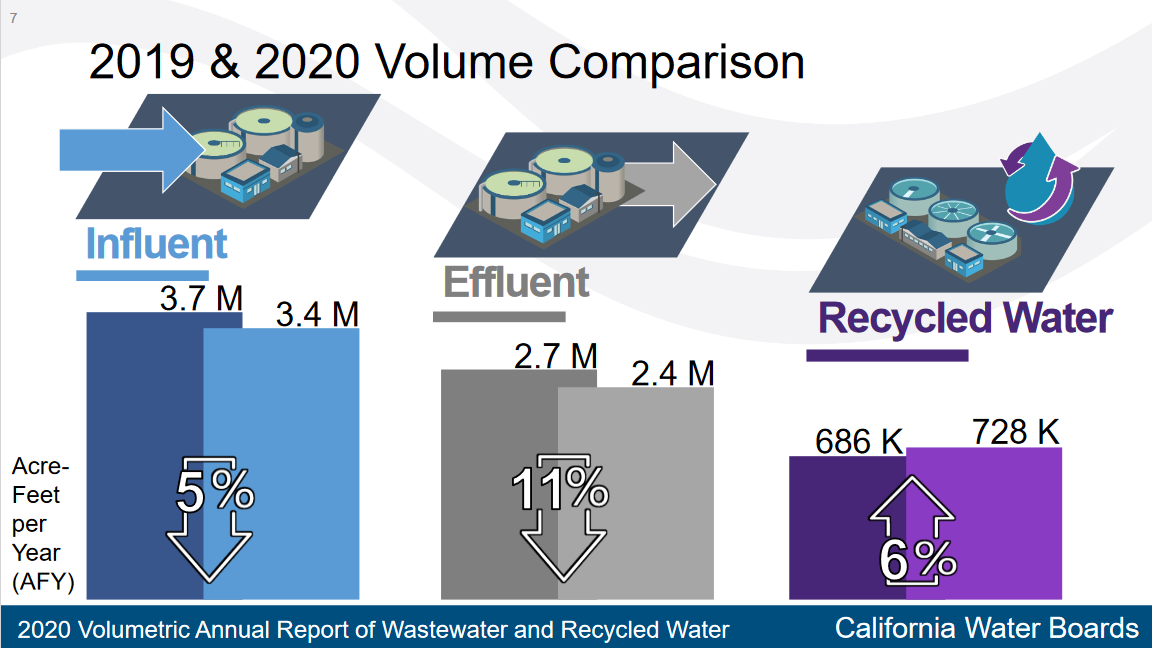

The graphic on the slide shows the comparison of influent, effluent, and recycled water volumes for the last two years given in acre-feet.

The graphic on the slide shows the comparison of influent, effluent, and recycled water volumes for the last two years given in acre-feet.

“The 2019 data is on the left, and the 2020 data is on the right, and it shows that influent and effluent have both decreased by 5% and 11%, respectively,” said Ms. Greenwood. “But despite that decrease, recycled water use has increased 6% to 720,000 acre-feet in 2020.”

Consistent with the 2019 data, the largest effluent discharge category was discharged to enclosed bays, estuaries, coastal lagoons, and ocean waters. Ms. Greenwood pointed out that it’s unknown if it’s a trend or just a year-to-year variation with only two years of reporting. The difference could reflect changes in water consumption due to conservation, variations in precipitation, or other factors.

“It’s a bit difficult right now to draw some conclusions on just two data points, so we’ll look to look forward to examining that in future years,” she said.

This chart compares recycled water use by category with 2019 data on the left and 2020 data on the right. Overall, there was a 6% increase for recycled water from 2019 to 2020, and within that recycled water, there were increases for both the agricultural irrigation and landscapes/golf course irrigation categories.

This chart compares recycled water use by category with 2019 data on the left and 2020 data on the right. Overall, there was a 6% increase for recycled water from 2019 to 2020, and within that recycled water, there were increases for both the agricultural irrigation and landscapes/golf course irrigation categories.

Ms. Greenwood reminded that it’s just the second year, so we don’t know if it’s a trend, but the facilities are getting better at reporting, and the shift could have come from categorizing their recycled water use rather than lumping it into the ‘other non-potable reuse’ category.

Looking at recycled water by region, the Los Angeles and Santa Ana regions have the highest potable uses, shown in light green; the Central Valley region has the highest agricultural reuse, shown in purple.

Looking at recycled water by region, the Los Angeles and Santa Ana regions have the highest potable uses, shown in light green; the Central Valley region has the highest agricultural reuse, shown in purple.

“We do expect to see more increases for groundwater recharge and particularly reservoir water augmentation, which could provide large volumes of recycled water to these categories by 2026,” she said.

The Water Boards fund planning, construction, and research projects through the water recycling funding program. Currently, twelve projects receive approximately $917 million in loans and grants that are still under construction for the state fiscal year 2021-22. When completed, those projects will provide an estimated 62,000 acre feet per year of recycled water for ag irrigation, landscape irrigation, groundwater recharge, potable reuse projects, and various other uses.

The Water Boards fund planning, construction, and research projects through the water recycling funding program. Currently, twelve projects receive approximately $917 million in loans and grants that are still under construction for the state fiscal year 2021-22. When completed, those projects will provide an estimated 62,000 acre feet per year of recycled water for ag irrigation, landscape irrigation, groundwater recharge, potable reuse projects, and various other uses.

The State Water Board has allotted about 3% of bond funding for research to advance the production and use of recycled water in California. The water recycling funding program selects research for funding to fill critical knowledge gaps, as well as identify impediments and other opportunities for the expansion of reuse around the state.

Ms. Greenwood noted that one project currently being funded is to identify the amount of wastewater that is available and feasible to recycle in California.

“This is a particularly exciting project that’s using data that’s collected from this reporting effort,” she said. “This research will add to our understanding of where in the state there is the greatest potential for recycled water use to occur. The project is scheduled to be completed by July 2022.”

Moving forward, the process is getting more refined and efficient. “We do have that mechanism now and a path forward even though we’re just in our second year of implementation, that this data set is establishing a baseline for us to make informed data-driven decisions,” said Ms. Greenwood. “Having this consistent annual data set will help us meet the implementation needs of the recycled water policy, fill data gaps for additional statewide water planning efforts, and assist state and local communities in evaluating the feasibility of increasing recycled water production and use in areas where the state need it the most.”

Moving forward, the process is getting more refined and efficient. “We do have that mechanism now and a path forward even though we’re just in our second year of implementation, that this data set is establishing a baseline for us to make informed data-driven decisions,” said Ms. Greenwood. “Having this consistent annual data set will help us meet the implementation needs of the recycled water policy, fill data gaps for additional statewide water planning efforts, and assist state and local communities in evaluating the feasibility of increasing recycled water production and use in areas where the state need it the most.”

She also noted that this data can inform water board programs such as water rights petitions, reviewing minimum instream flows, the water recycling funding program, and the human right to water. Externally, the Department of Water Resources can use this data to compare what’s being presented in urban water management plans.

“These continued interactions will continue to expand the utility of this dataset and provide insight into additional potential connections moving forward,” she said.

“So you can make a case that you only really need two points to draw a line, but you need that third point to confirm that it can be a trend,” she said. “So looking forward into our third year, the baseline is going to continue to get clear. And we’re going to start to have more conversations around this data and continue to have more interest in finding intersections. So it’s important to start looking at potential trends and be proactive in discussing not only what is being reported but how it truly affects the future. So with the volumetric end report, we’re continuing to commit to using high-quality data to support the long-term stewardship of California’s water resources.”

“So you can make a case that you only really need two points to draw a line, but you need that third point to confirm that it can be a trend,” she said. “So looking forward into our third year, the baseline is going to continue to get clear. And we’re going to start to have more conversations around this data and continue to have more interest in finding intersections. So it’s important to start looking at potential trends and be proactive in discussing not only what is being reported but how it truly affects the future. So with the volumetric end report, we’re continuing to commit to using high-quality data to support the long-term stewardship of California’s water resources.”

Chair Joaquin Esquivel acknowledged former State Water Board member Fran Spivy-Weber, who was a staunch advocate of water recycling. “This is all generational in the making, insofar as the effort on the regulatory side to bring more certainty to projects, the dollars to also now really be accelerating the ability and the affordability of water recycling throughout the state,” he said. “We have just an incredible opportunity to take that data and that information and turn it into just great decision making at the local level and support for projects and investment in critical resources in the face of drought.”

Board member Sean Maguire acknowledged it’s difficult to draw a line and certainly make any conclusions about the trend, but there’s no doubt that the trend will be positive. He acknowledged the many projects under construction or development: San Diego, Los Angeles, Santa Clara, and others. “The question ultimately is, what is the slope of that line, and how can we at the board support a higher slope, getting closer to our ultimate goals to whatever is feasible within all the different constraints that we have?” he said.

Chair Esquivel asked if the survey includes any questions asking the water agencies to estimate what they anticipate coming online in the next few years?

Chair Esquivel asked if the survey includes any questions asking the water agencies to estimate what they anticipate coming online in the next few years?

Chief Deputy Director Jonathan Bishop replied, “What we’re really doing is requiring them to report on what they did, not on what they’re planning. Part of that was very purposeful. The previous ones were questionnaires. And it was very hard to determine what was actually being recycled, what was being hoped to be recycled, or what was being discharged in a way that might be considered use. So we got away from the questionnaire approach; this is reporting on their volumes in and out and what’s in different pots.”

Senior Environmental Scientist Laura McClellan added, “The urban water management plans that DWR reviews ask questions like that, and that’s part of the coordination that we have with DWR is they’re doing that analysis to see where they anticipate growth in different areas of the state and then cross-checking it with our data.”

Chief Deputy Director Jonathan Bishop noted, “Another thought is that most of the recycled water projects get some money from us in one way or another, so we have a preview of what is going to be going online in a few years by what we’ve been funding in the last few years.”