The impact of climate change on flood risk in the Delta varies by location, which means the fixes will too.

“It’s not one Delta, it’s many different regions and they’re each going to need different adaptation strategies,” said Andrew Schwarz of the state Department of Water Resources in his talk on key findings from the Delta Adapts Flood Risk Analysis.

The north Delta is largely spared from increased inundation thanks to the Yolo Bypass, which absorbs high flows on the Sacramento River system. But by mid- and late-century, the risk of flooding is high across the rest of the Delta.

The San Joaquin River system lacks a bypass “so those big flows come into the south Delta and cause a lot of flooding,” Schwarz explained. “And sea-level rise comes in from the ocean and causes flooding in the central Delta.”

Next steps include identifying region-specific ways to help the Delta adapt to future flood risk.

Author: Robin Meadows | Image: Map shows areas of strongest climate change influence throughout the Delta. Map courtesy of Andrew Schwarz; photo by Rick Lewis.

Creating floating wetlands can sequester carbon and help reverse Delta subsidence.

Creating floating wetlands can sequester carbon and help reverse Delta subsidence.

In 2005, a story by some engineers caught Steven Deverel’s attention: they described witnessing some dredged sediment go underneath some peaty soil in the Montezuma Wetlands and amazingly lift up the ground five to ten feet–in other words, the peat was floating on water. Deverel quickly realized the implications and teamed up with the Metropolitan Water District’s Curt Schmutte and the UC Davis Center for Watershed Science to study the potential benefits of these rafts of reeds and mud.

“We all pretty much accept that the Delta food web no longer adequately supports native species,” he said at the conference.

But creating bobbing islands of matted marsh plant roots and soil, said Deverel, not only absorbs carbon from the air as the plants grow, but recycles it back into the food web via microorganisms that are in turn consumed by fish. There is evidence that floating islands of peat occurred naturally in the Delta in the 19th century—some reportedly large enough to harbor herds of animals during floods.

But for now, the only floating wetlands are in Deverel’s eight open water tanks beside the Mokelumne River. Similar to propagating plants via cuttings, two years ago his team transferred cubes of peaty loam from the Delta to the tanks, which have since grown dense reedy thickets with gnarled beards of stringy roots. According to Deverel, on a larger scale, these floating wetlands could help reverse subsidence at the Delta’s deeply depressed islands, in addition to acting as carbon sponges.

Author: Isaac Pearlman | Photo: Curt Schmutte

Researchers seeking to learn more about accretion at Bay marshes have gained greater insight into the site-specific nature of sediment deposition.

Researchers seeking to learn more about accretion at Bay marshes have gained greater insight into the site-specific nature of sediment deposition.

The findings have important implications for estimating sea-level rise vulnerability and understanding restoration goals and possible outcomes at locations through the region, said United States Geological Survey research ecologist Karen Thorne in her conference talk. Wetlands can build their elevation to keep pace with sea-level rise through organic matter input as well as mineral deposition.

But there’s a lot scientists don’t yet know about accretion rates and processes at different marshes throughout the Bay. Marshes at the Petaluma River, San Pablo Bay, Rush Ranch, Browns Island, and Miner’s Slough are all keeping pace with or exceeding sea-level rise, according to data collected by USGS between 2016 and 2021.

But to gain greater insight into how and when accretion occurs on a site-by-site basis, researchers zeroed in on two of these marshes, Petaluma River and Rush Ranch. Using sediment traps, vegetation surveys, and water level/salinity monitors, they determined that organic deposition was two times larger at Rush Ranch, that mineral deposition at both sites varied significantly throughout the year, and that the highest deposition rates overall occurred in May and June.

Thorne and a USGS colleague are now launching a new study to better understand temporal variability in sediment delivery to a marsh at Eden Landing Ecological Reserve.

“The motivation is to more accurately predict the fate of marshes,” Thorne said. “We really need to know how much sediment is being delivered, and how that varies by tide and wave conditions, in particular for South San Francisco Bay, where so much restoration is planned and there’s a critical need for habitat persistence for endangered species.”

Note: In a new Science-in-Short podcast, Estuary reporter Ariel Rubissow Okamoto interviews Thorne and fellow conference presenter Jessie Lacy about their planned research on micro-changes in the South Bay margins at Whale’s Tail Marsh, which hits the mud this June. The research will fill a critical gap in understanding of daily and seasonal sediment dynamics. Listen here: Drift, Drop or Floc? Tailing Sediment as it Moves Through Marsh Margins.

Author: Nate Seltenrich

By the end of the century, climate change is expected to make the Delta’s water saltier and warmer.

By the end of the century, climate change is expected to make the Delta’s water saltier and warmer.

Sea level rise will likely boost salinity near and downstream of the Sacramento-San Joaquin river confluence, threatening freshwater species.

“How much more water will reservoirs need to release to counteract the effects of sea-level rise on salinity?” asked Noah Knowles of the U.S. Geological Survey during his conference talk.

Depending on the climate scenario, preliminary results suggest that the answer ranges from about 150,000 acre-feet to 1.5 million acre-feet per year; the latter is enough to supply up to 3 million California households. In addition, hotter air will likely push Delta water temperatures up by 1 to 3⁰C. This means the mortality threshold for Delta smelt—24⁰C—could be exceeded for an additional one-to-four months every year, bad news for a fish that is already barely hanging on.

Author: Robin Meadows | Delta station at Shag Island measuring salinity and water quality remotely, near wildfire smoke. Photo courtesy USGS.

Both managed and natural features in Suisun Marsh are “engines of productivity” for fish, but those engines could shut down as early as 2100 if sea-level rise continues as predicted.

Both managed and natural features in Suisun Marsh are “engines of productivity” for fish, but those engines could shut down as early as 2100 if sea-level rise continues as predicted.

The marsh, the largest contiguous tidal wetland in the San Francisco Estuary, is a rich complex of meandering brackish sloughs, natural tidal marshes, and muted seasonal ponds managed by duck clubs. Salinity is controlled by gates installed in the 1980s. Researchers at the UC Davis Center for Watershed Science have determined that productivity (chlorophyll, zooplankton, and dissolved organic matter) is highest at the terminal ends of the sloughs and in the ponds.

“There is considerable evidence that this sort of productivity creates an attractive environment for many native and naturalized fishes in the Estuary,” said John Durand of the center’s Suisun Marsh Fish Study, during his presentation on the subject. “And there’s a place for managed wetlands and working landscapes to support restored sites.”

A study conducted by the center found that in 2050 some areas will be inundated by mean high tides, but will still drain. By 2100, however, projections show that all the managed wetlands will be inundated every high tide. Regarding 2150, he said, “if we don’t take actions to mitigate sea-level rise, and the patterns continue as we predict, the entire marsh will become more of an embayment than a marsh, and those very attributes that make the Suisun Marsh desirable as a habitat will be gone.”

Author: Aleta George | Image courtesy of John Durand

Two Delta smelt researchers project the endangered fish won’t be too happy in a climate-changed estuary.

Two Delta smelt researchers project the endangered fish won’t be too happy in a climate-changed estuary.

In one talk, UC Davis’ Levi Lewis took a hard look at the future for wild fish that “have adapted for over 4,000 generations to conditions that no longer exist.”

Lewis modeled how the species’ reproductive patterns, growth, and migratory life history might change with hotter, clearer and saltier water in the Delta. His models demonstrated hatching shifts of about 60 days, with hatching earlier in warmer years and later in cooler years. Loss of turbidity also proved challenging to the beleaguered fish.

“Their growth rates decline by 36% when the water is both warm and clear,” he said.

Lewis also explored how climate change may affect life history differences in terms of fish residency and migration between fresh and brackish water, with few freshwater resident fish persisting in warmer years. The fish are already “rare and patchy” today, Lewis said. Climate change will likely only further disrupt historic patterns.

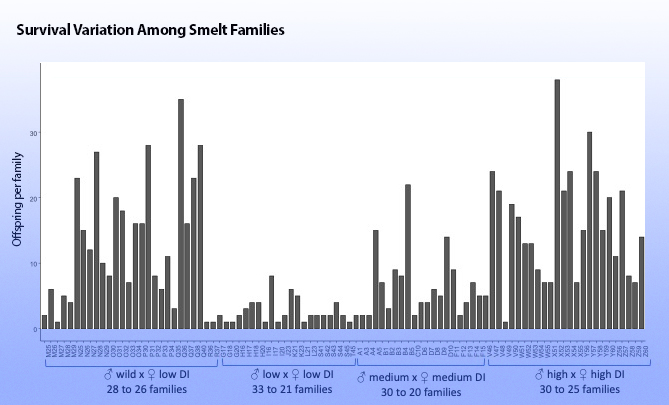

So how might the genetically preserved specimens living in labs until more habitat can be restored fare in this brave new Delta? In another talk, UC Davis colleague Joanna Griffiths described raising four families of different combinations of male and female wild and domesticated smelt at 15°C and 18°C water temperatures to see if they contained appropriate genetic material to adapt.

“Despite Covid, fires, and a direct lightning strike on our facility, we were able to sample 1,000 fish,” she said. “Very wild and very domesticated fish had high survival rates, but fish of medium domestication indices did not, and we’re still trying to understand that,” she said. “But smelt [in the lab] seem to have a limited capacity to adapt to temperature change.”

Author: Ariel Rubissow Okamoto