Estuary News sent reporters to the 11th Biennial Bay-Delta Science Conference, held virtually earlier this month. The theme of this year’s conference was Building Resilience Through Diversity in Science. In this second of four special editions of Pearls we highlight new science on Bay-Delta birds and fish.

Severe thiamine deficiency is plaguing the Sacramento River’s Chinook salmon, causing elevated mortality rates in juveniles and adding another obstacle to the species’ already uncertain future.

Thiamine, or vitamin B-1, is a nutrient necessary for basic cellular-level metabolism and critical to every lifeform. Since early 2020, staff at the Central Valley’s salmon hatcheries have observed symptoms of thiamine deficiency in juvenile fish—especially erratic swimming and an inability to feed (tests confirmed the condition was affecting the fish).

In her conference talk, Rachel Johnson of NOAA’s Fisheries Ecology Division explained why she and her colleagues suspect anchovies may be the source of the problem: Anchovies contain an enzyme called thiaminase that breaks down thiamine in creatures that eat them. Due to recent shifts in forage-fish communities along the California coast, anchovies have become the dominant prey species available for the Central Valley’s Chinook. This, researchers believe, has caused Chinook salmon to over-consume the vitamin-destroying enzyme.

Fortunately, mitigating the problem seems relatively straightforward, at least for captive hatchery fish. Trials conducted last year suggest that injecting female salmon prior to spawning with a thiamine booster essentially eliminates deficiency symptoms in their offspring.

“It’s much like humans taking a prenatal pill,” Johnson says, adding that the injection technique has proven “wildly successful.”

Now, Johnson and colleagues are tracking tagged juvenile salmon in real-time as they migrate downriver toward the ocean to see if the booster given to their mothers improves their survival compared to those deprived of the vitamin during development. Unfortunately, the conditions that scientists believe are causing thiamine deficiency in the first place persist.

“There is no evidence that the marine food web has returned to normal,” Johnson says.

Author: Alistair Bland | Image: Travis Webster, USFWS

Restoration often involves tradeoffs among species and habitats; the South Bay Salt Ponds Restoration project is no exception.

As USGS biologist Alex Hartman explained in his presentation on breeding waterbird declines in the south Bay over the past two decades, converting managed ponds to tidal wetlands may be good for the Ridgway’s rail and salt marsh harvest mouse, but less so for colonial waterbirds like the American avocet, black-necked stilt, and Forster’s tern. Formerly abundant in the former salt ponds, all three declined during the initial stages of restoration.

Comparing 2001 and 2019 surveys, avocet numbers fell by 13.5 percent and stilts by 30 per cent. Nesting abundance of avocets, stilts, and terns dropped between 2005 and 2019. Some former colony sites are now inactive, and nesting islands have been lost to erosion. Observations showed that these waterbirds used managed ponds more than expected, tidal marsh and mudflat less than expected. To compensate, islands have been built in remaining managed ponds and social attraction methods (decoys and recorded calls) used to draw the birds to them.

“Numbers increasing at these other sites as of yet have not made up for steep decline elsewhere,” said Hartman.

The project’s goal is to restore 50-90 percent of salt ponds to tidal action. Retaining managed ponds may help limit future declines in breeding waterbird populations. The wild card is the burgeoning population of California gulls, voracious predators of eggs and chicks.

“There have been limited efforts to dissuade gulls from establishing colonies in some areas, but no real population control,” he added.

Author: Joe Eaton | Above: Nesting abundance of colonial waterbirds in the South Bay has declined from peaks in the late 2000s.

Researchers who analyzed 19th century Central Valley Chinook salmon remains have made a surprising discovery about the fish’s historical life history and migrations.

In a conference talk, Malte Willmes, an assistant project scientist with UC Santa Cruz’s Institute of Marine Sciences, described examining 43 Chinook salmon otoliths found beside the lower Feather River at a site dated to the mid-1800s.

Otoliths, or ear stones, are composed of calcium carbonate and, because they grow throughout a fish’s life, can tell scientists a great deal about the environment a fish lived in. For instance, otolith growth layers can carry isotopic tracers of salinity. By analyzing these biochemical clues, Willmes and his team concluded that the fish in their samples never left the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

Modern Chinook, of course, are legendary for their epic migrations, which include years of traveling through the open ocean. Willmes’s research tells a new story: “It appears that these fish moved out into the low and medium salinity areas, and not into the Pacific Ocean,” he says.

The fish then remained in the Delta most of their lives. “We think we’ve discovered a life history strategy that we don’t see in the modern Chinook of the Central Valley,” Willmes told conference attendees.

He adds that these results do not mean that all the Central Valley’s salmon once behaved this way. Rather, he suspects that California’s waterways, when still unimpaired, afforded Chinook populations an additional life history strategy not seen today. Willmes suspects that routine flooding and high outflow from the river systems through the Estuary historically created high-quality habitat that could have supported adult fish within the Estuary—conditions since sacrificed to water diversions and habitat simplification.

Author: Alistair Bland | Image: Adi Khen

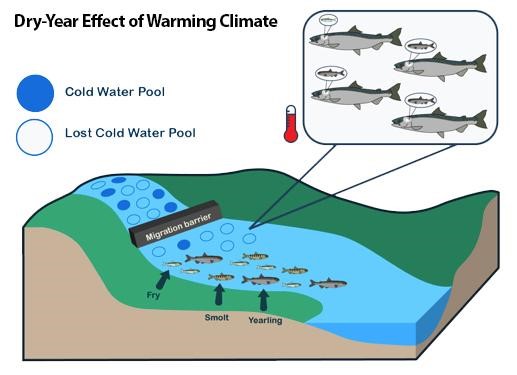

Evolving in a volatile environment, spring-run Chinook salmon have developed a variety of life-history strategies, with different conservation implications.

Evolving in a volatile environment, spring-run Chinook salmon have developed a variety of life-history strategies, with different conservation implications.

Some have what Flora Cordoleani, in her presentation “Years in Their Ears,” labeled a yearling strategy, leaving the streams where they were hatched later and at a larger size than other juveniles. Cordoleani analyzed the otoliths (ear bones) of salmon returning to spawn to determine their natal streams, from variations in strontium isotope ratios across the landscape, and their age when they left them, from the structure of the otoliths.

“Otoliths are incredible markers because they record the strontium signature of the water and the age of the fish at the same time,” she said.

She focused on Butte, Deer, and Mill Creeks, the last Upper Sacramento River tributaries with self-sustaining spring run Chinook populations. Comparing the life histories of returning salmon for years with varying hydrological conditions, she found that yearling migrants were critical to sustaining the Mill and Deer Creek populations during drought conditions. But their strategy requires access to streams with cool summer temperatures, many currently blocked by dams. Although suitable yearling rearing habitat is predicted to shrink due to climate change, Cordoleani said it could be tripled if access to upstream thermal refugia was restored.

In contrast, the success of the Butte Creek population depends on juveniles that migrate at a younger age and need continued access to floodplain rearing habitat downstream in the Sutter Bypass.

Author: Joe Eaton

How do San Francisco Bay’s mudflats support the multitudes of shorebirds that use them in winter and during spring and fall migration?

USGS biologist Laurie Hall says resource partitioning—divvying up the available food in a structured way—is the key. With bill length and shape ranging from the short straight beak of the least sandpiper to the sickle beak of the long-billed curlew, shorebirds find food at different depths in the mud.

The subject of her research and talk, the western sandpiper (the Bay’s most abundant shorebird) goes a step farther, partitioning by age and sex. Female westerns have longer bills and greater body mass than males. At Dumbarton Shoal in the South Bay, Hall and her colleagues analyzed carbon and nitrogen isotopes in the sandpipers’ blood and in food sources. They found that in winter, all the birds had similar diets. In spring, however, females ate more deep-burrowing polychaete worms, while males ate more surface-dwelling invertebrates, biofilm (communities of bacteria and other microorganisms), and microphytobenthos (diatoms and other algae within the biofilm.) Juvenile males in spring consumed more microphytobenthos than any other demographic group.

“The birds are foraging on biofilm and microphytobenthos because they’re high in the fatty acids they need to fuel their migration,” she explained.

Hall hopes her data will help resource managers make informed conservation decisions for shorebirds, targeting regions of high biofilm productivity: “That will be increasingly important as sea level rise and changes in water management reduce available foraging habitat.”

Author: Joe Eaton

Image: Diets of western sandpipers of both sexes and all ages are similar in winter but differ in spring, when males and juveniles eat more biofilm

Predictive models can help identify hotspots of bird diversity in the Delta and protect bird populations from future changes in land use and climate.

Focusing on riparian species, such as song sparrows, and waterbirds like ducks, the scientists from Point Blue Conservation Science used data from field surveys to build better predictive models future bird distribution and habitat conditions in the Central Valley and Delta. Point Blue took factors like general and specific habitat type, vegetation species, and surrounding land use into account. Scientists chose nine species to represent a range of riparian habitat needs, showing a diversity of nesting preferences, diet, and migratory status for each group of birds.

“These maps give us a way to forecast how these birds might respond to a changing landscape in the future,” said Kristen Dybala, one of the lead scientists on the study in her conference talk. “But also, because we expect these species to collectively represent the riparian ecosystem, we can put all these maps together to get a sense of current hotspots of riparian diversity on the landscape.”

For waterbirds, the models also accounted for seasonal changes due to the presence of migratory species and the shifting nature of aquatic habitat. The models can be altered to highlight different priorities, such as overall bird diversity, or locations that are particularly important to more rare species. For riparian birds, the preliminary maps show critical hotspots in the upper Delta, whereas the focus is on the central Delta for waterbirds.

“We hope to use these results to identify, under future landscape scenarios, how do these hotspots move, how do these important areas change, what are the threats to these areas today, and how can we use that to inform conservation,” said Dybala.

Author: Elyse DeFranco | Image: Riparian habitat photo by Amber Manfree; Bird conservation hotspots in the Delta

Conference abstracts and recordings of the actual talks are available online, with some log in requirements, for the next few weeks.