A recap of the webinar featuring Tim Quinn, formerly with ACWA, Tracy Quinn with the NRDC, and author John Fleck

A week doesn’t go by without someone saying there are water wars underway or about to kick off in California. How we manage and govern water is critically important to people, the environment, and the economy. But, are we really at war? Really? Do we believe there are always victors and vanquished? What is the impact of telling ourselves and others this is warfare, when in reality it is simply the messiness of working together in community?

So, we’ve gathered a panel to answer the question: Water wars, what are they good for?

The panel:

Timothy Quinn retired in 2018 after a very eventful 40-year career in California water management and politics. His water career began in 1978 when he chose groundwater management as the topic of his PHD dissertation in economics at UCLA, while working with a group of water economists at the RAND Corporation. In 1985, Tim started a 22-year stint at the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, most of it as Deputy General Manager. In 2007, Tim became the Executive Director of the Association of California Water Agencies, leading the association to legislative and other successes on behalf of ACWA’s roughly 450 public agency members. In 2019, Tim was the William C. Landreth Visiting Fellow at Stanford University’s Water in the West Program, where he taught a course on water policy and wrote a paper on governance based on his career experience.

John Fleck wrote about science for the Albuquerque Journal for 25 years. He is also an author of two books on the Colorado River: Water is for Fighting Over: and other Myths About Water in the West and Science Be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River, a collaboration with Eric Kuhn. He also wrote The Tree Rings’ Tale, a book for middle-school aged kids about the climate of the West. He is now the director of the University of New Mexico Water Resources Program. John Fleck’s blog can be found here: http://inkstain.net/fleck

Tracy Quinn’s practice area has encompassed a wide range of water-related issues, including resources planning, infrastructure design, and industrial compliance with regulations. Most recently, Quinn has focused on the unique efficiency challenges and opportunities that face California as it responds to unprecedented drought and developing product standards for conserving water. She earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in agricultural and biological engineering at Cornell University and is a registered civil engineer in California. She is based in NRDC’s Santa Monica office. Tracy Quinn is also on the Metropolitan Water District’s board of directors, representing the City of Los Angeles. More information on Tracy Quinn here: https://www.nrdc.org/experts/tracy-quinn

The moderator is Lisa Beutler, an AWRA past president and executive facilitator at Stantec, is no stranger to wicked problems. She helps communities and organizations solve problems and make decisions. A nationally recognized conflict resolution and public policy specialist, she has worked on some of the most complex water resources issues in the United States.

The host is Mike Antos, a watershed social scientist with Stantec and visiting scholar at UC Irvine’s Anthropology Department.

Here’s what they had to say, only edited for clarity …

MIKE ANTOS

I have to admit that I sagely say more than once a week, ‘words matter,’ and many nod their heads along with me that they agree Later, Lisa is going to remind us that it’s well understood that words create worlds. The question I really wanted to think through, and I’m super excited to have everyone think it through together today is, what do we conjure for ourselves and others, especially those who are watching only from a distance, when we say that our lives are about ‘fighting water wars’?

I have to admit that I sagely say more than once a week, ‘words matter,’ and many nod their heads along with me that they agree Later, Lisa is going to remind us that it’s well understood that words create worlds. The question I really wanted to think through, and I’m super excited to have everyone think it through together today is, what do we conjure for ourselves and others, especially those who are watching only from a distance, when we say that our lives are about ‘fighting water wars’?

Aaron Wolf at Oregon State University has done some amazing work on this, at times alongside Peter Gleick at Pacific Institute. Of course, Peter has been recognized for his water diplomacy. Aaron’s work, he says, and this is a quote, ‘water management is conflict management.’

We have a concept of wicked problems. I’m originally from New England, so I’m allowed to call it wicked. And the idea of a wicked problem is that it’s just so complex and interconnected with other things that you’d never really actually solve them; you can only manage them. One could say that it’s very much like relationships and very much like diplomacy. Tony Brand, a World War II pilot and later an MP in the UK, is quoted as saying that ‘war is the ultimate failure of diplomacy.’

So as I and others wrote in the invitation today, we talk about how we manage and govern water. It’s critically important to people, the environment, and the economy. But are we really at war when we do that work? Really? Do we believe that there are always victors and vanquished? What is the impact that we have on ourselves and others by saying that this is warfare when in reality, it’s more like diplomacy; it’s more like the messiness of a wicked problem of working together and in community.

I’m going to turn it over to my colleague and friend, Lisa Beutler. She’s an executive facilitator at Stantec, past president of the American Water Resources Association, and a go-to when confronting wicked water problems. And she’s also my friend.

LISA BEUTLER, Moderator

I’m really excited about the panel that’s been pulled together. It’s fair to say that that we have a pretty legendary panel with us today. Tim Quinn is going to be our first speaker and launch us off into this conversation. This has been a fun process getting ready, as Tim himself has gone through an evolution, and he’ll be talking about that. We also have Tracy Quinn, not related to Tim; she comes from the environmental community, and she’s also an engineer. And then we have a wonderful author, John Fleck.

I’m really excited about the panel that’s been pulled together. It’s fair to say that that we have a pretty legendary panel with us today. Tim Quinn is going to be our first speaker and launch us off into this conversation. This has been a fun process getting ready, as Tim himself has gone through an evolution, and he’ll be talking about that. We also have Tracy Quinn, not related to Tim; she comes from the environmental community, and she’s also an engineer. And then we have a wonderful author, John Fleck.

First, we’re going to start with defining what war is. Merriam Webster says that war is a state of hostility. It’s a conflict or an antagonism. It could also be a struggle or a competition between opposing forces for a particular end. Tim is a nationally acclaimed water professional, and in most settings, anyone would consider you to be a formidable opponent. In fact, I don’t think very many people would want to tread on the other side of your argument, so you have a strong reputation. You are just one of a handful of people awarded the National Water Resources Association’s Water Buffalo Award. This award is only given to select individuals that are widely respected by their peers for their knowledge and their force of personality.

You have also been quoted as saying, ‘war is easy, collaboration is hell.’ So given your reputation as a powerful and skillful combatant, I’d like to know what brings you to this discussion today; the whole idea of questioning the premise of a water war.

TIM QUINN

I want to start by challenging a couple of things you said. One is, you described me as a combatant, and I have no doubt that some people listening to this call think of Tim Quinn as a combatant. But I have to tell you that Tim Quinn does not think of himself as a combatant; I view myself as a collaborationist. I’ve tried to do collaboration for almost 30 years in managing California’s water.

I want to start by challenging a couple of things you said. One is, you described me as a combatant, and I have no doubt that some people listening to this call think of Tim Quinn as a combatant. But I have to tell you that Tim Quinn does not think of himself as a combatant; I view myself as a collaborationist. I’ve tried to do collaboration for almost 30 years in managing California’s water.

I have, from time to time, been a warrior in my life. I have been a warrior at times when I had to be. But you know something? I don’t believe I ever accomplished anything great as a warrior, and being involved in water wars resulted in some of the worst enemies in my career.

The other thing I want to complete in content. War is easy; collaboration is hell. I have said that a thousand times, but I always follow it with ‘but’ – collaboration is the only way to deal with the wicked problems we have to deal with in California water policy. There’s nothing easy about collaboration, but it’s the only way to make progress. I think that’s certainly true today.

To understand how I view this notion of water wars, you have to put it in a historical evolutionary context. After I retired, I became a fellow at Stanford University. My time at Stanford gave me a chance to be reflective about my career and the forty years that I had spent almost all of it at the center of California water policy in one way or another.

I also read a lot of political science literature. Political scientists argue, I think correctly and certainly for water, that water policy decision-making proceeds in eras or stages. The first era is the development era, where you build infrastructure to provide water supply. For California water, that happened from the turn of the 20th century until pretty much the 1970s. The development era was characterized by a governing system in which decisions were made top-down by powerful water agencies, which the political science literature calls managerial and almost always adversarial.

Think dynamite in the building of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Think about the Governor of Arizona bringing out his national guard to try and stop the building of the Colorado River Aqueduct. Think about John Muir and the building of Hetch Hetchy that was arguably a significant factor in his death.

There was always a lot of conflict. There were winners and losers. Those were the rules of the game. The powerful water agencies had a set of rules that allowed them to move ahead, even if they had a lot of collateral damage.

That collateral damage led to the regulatory era in which we started to think about the environment and protect the environment. Our policy goals did a 180, from low-cost water supply development, no matter what, to environmental protection, if you read the laws, no matter what.

It was interesting to me when I was thinking about this at Stanford was that the governance did not shift. Governance was still top-down. It was still managerial. It was still winner take all. And it was winners and losers.

We’re now at a stage where that kind of warfare – not sure I like the word war, but I do believe it’s adversarial and not collaborative decision making. Through much of the history of California water, we have had adversarial winner take all, winners and losers, processes. But that’s no longer true.

In my career in the mid-1980s, I viewed myself as a collaborationist landing in a field of warriors. At Metropolitan Water District, where I was working, the mantra was ‘complete the State Water Project’ aka ‘overcome its opponents and get your will because you signed a contract,’ but I worked for a man named Carl Boronkay who knew that wasn’t the future. He told me years later he hired me because he knew I was a collaborationist and that worlds were changing.

We created access to the system, and desirably so, from groups who had been previously marginalized, and as these groups became more active, top-down wasn’t going to work anymore. We needed to move into the third era, the collaboration era, where we allow more people to be active in the decision-making process; anyone who thinks they are affected ought to be involved. Top-down does not work with open, transparent decision-making where you have multiple parties and multiple benefits. You can’t top-down that process; we have to develop ways in which we can collaborate.

LISA BEUTLER

You say we have to stop the top-down, but why?

TIM QUINN

Because the people previously marginalized can stop you in your tracks. The best example of that is the California Bay-Delta. We’ve been getting governance wrong there for 20 years. We keep trying to do top-down governance, and with that kind of problem, you can never succeed with top-down governance. You have to transition if you want to succeed. The old rules allowed a project developer or proponent to proceed even if there was a lot of collateral damage. The new rules make it really difficult to get something done. I think this has led to the collaborative era.

LISA BEUTLER

Tracy, let’s go to you. Your organization is the Natural Resources Defense Council. And your role is to ensure the rights of all people to clean air, clean water, healthy communities, and to battle urgent threats. So you are confronting pressing problems. Your organizational title explains that you are defending air, water, communities, wild places – the entire premise of your organization is that you’re under siege. So given your personal experiences and your role as a protector, how does this concept of water wars work for you and impact the way you think about or approach your work?

TRACY QUINN

For those that don’t know me, I’m Tracy Quinn. I’m the director of the California Urban Water Policy for the Natural Resources Defense Council. If you’re not familiar with our organization, NRDC is an environmental group with nearly 700 lawyers, scientists, and policy experts working in offices across the US and Beijing. As for our water program in the early 1970s, NRDC helped win passage of the Clean Water Act, our nation’s bedrock water pollution law. And since then, we have continued to fight for a safe, sufficient, and affordable water supply. The tools that we use to pursue our mission include litigation, legislation, publishing scientific papers, and working with local governments and community-based organizations.

For those that don’t know me, I’m Tracy Quinn. I’m the director of the California Urban Water Policy for the Natural Resources Defense Council. If you’re not familiar with our organization, NRDC is an environmental group with nearly 700 lawyers, scientists, and policy experts working in offices across the US and Beijing. As for our water program in the early 1970s, NRDC helped win passage of the Clean Water Act, our nation’s bedrock water pollution law. And since then, we have continued to fight for a safe, sufficient, and affordable water supply. The tools that we use to pursue our mission include litigation, legislation, publishing scientific papers, and working with local governments and community-based organizations.

For most of my career at NRDC, my focus has been on advancing water efficiency, and in the last couple of years, that has evolved into including addressing emerging contaminants and water affordability. Prior to joining NRDC ten years ago, I worked for nearly a decade as a water resources engineer in Southern California. And for some balance, I’m also on the board of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. So I think I bring a little bit of a broad background to this issue.

To address your question directly, yes, the things that I and the NRDC care about are under siege. With climate change, emerging contaminants, and a growing population, the gap is widening between the water made available by nature and the water that we need for our farms, our homes, and our businesses. Fish populations are plummeting. Over a million Californians don’t have clean water in their taps due to pollution, groundwater overdraft, and drought. And every year, hundreds of 1000s of Californians have their water shut off because they can’t afford to pay their bills. The stakes are high.

Now, I haven’t been in the trenches of deeply contentious litigation like some of my colleagues, some of the people on the panel today, and the audience, so I might be a little more optimistic than others from the environmental community. But I believe we can rise up to meet the challenges ahead if we stop trying to win this imaginary war and just have honest, thoughtful, open-minded conversations. Today, I’m hoping we can pull back the curtain on some of our preconceived notions about each other and better understand the important role we all play in the ecosystem of water management.

This is something that I learned early on was a helpful tool. When I first started at NRDC, and I was sitting in stakeholder meetings, I felt at times that my opinions or thoughts on different approaches were dismissed. I was lucky to have an honest conversation with someone from the water supplier community, and I asked, ‘why do you seem so dismissive of the things that I’m saying in this meeting?’ He said to me, ‘You’re coming from an environmental group, and you’re probably some lawyer, so there’s no way you have any idea about how my system works.’ And I said, ‘Let me stop you there. I am a professional engineer, and I actually designed some of the infrastructure in your system.’ And from that moment on, we were able to have a much more open dialogue going forward, and we could hear each other in the conversations. That’s a lesson I learned early on about really breaking down some of those barriers.

For this conversation, it’s important to start by reframing how we look at the preferred advocacy tools used by different stakeholders. Litigation, for instance, is inherently adversarial. There’s going to be winners and there’s going to be losers. But as Tim has acknowledged in some of his writing, litigation is often the driver for a more collaborative approach. And quite frankly, litigation is sometimes the only way that enviros can get a seat at the table.

Strong regulatory frameworks are also framed as adversarial, pitting the regulated community against the regulators and the environmental advocates. But regulatory frameworks play an important role in driving agreement. Take the Bay-Delta Water Quality Plan, for example. We need it because the law requires it under the Porter-Cologne Clean Water Act, and otherwise, the feds are going to step in. It serves as an incentive for stakeholders to come to the table and ensure that the agreements are implementing scientifically based standards. It could serve as a backstop to ensure that the implementation actually happens. It’s there to apply to the people not in the agreement. As for how the agreement gets drafted, it feels like we’ve been starting from a place of ‘how much water can we afford to leave in the river,’ when an approach that might get broader support is ‘how do we concurrently diversify our water supply portfolio so we can also sustain the economy.’

Instead of thinking of litigation as aggression, we can reframe it to understand that litigation can drive a strong regulatory framework, which can then incentivize voluntary agreements to have more flexibility for implementation than the state can require. It’s difficult to jump to the agreement before you have those parameters in place. And so each of these things serves as a role in this ecosystem of water management.

LISA BEUTLER

One of the things that Tim referred to was the ‘best alternative to a negotiated agreement’ or the BATNA. And the only thing that made the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act was having both sides of the equation there.

John, you spent 25 years of your youth reporting on science and the environment for the Albuquerque Journal. There’s this really wonderful passage in one of your books. You write, ‘as a newspaper reporter covering the region’s water supply, I was steeped in the old narratives of the crisis of communities at risk of running out of water. Monthly, I asked for copies of the water utilities pumping reports. And I made a habit of routinely checking the US Geological Survey’s groundwater monitoring well data. I was ready to pounce at the first sign of failure, but our water use just kept dropping, and our aquifer kept rising, grudgingly at first, but then with fascination.’

So with that, John, tell us how your own stories and the stories you tell about other people inform how we think about the topic of water wars.

JOHN FLECK

I always feel a little bit weird in these conversations because I’m the outsider; I’m the journalist, or a former journalist, and now an academic. I just stand on the outside and kibitz on these issues and provide my commentary while people like Tim and Tracy actually have to try to solve problems. So it’s a little bit easier for me on the outside to make these grand pronouncements.

I always feel a little bit weird in these conversations because I’m the outsider; I’m the journalist, or a former journalist, and now an academic. I just stand on the outside and kibitz on these issues and provide my commentary while people like Tim and Tracy actually have to try to solve problems. So it’s a little bit easier for me on the outside to make these grand pronouncements.

It’s really impossible to extricate the story that I told in that book and the narrative that I offer here about my attitude toward the notions of water wars and water collaboration. You can’t extricate it from my background as a journalist because I lived in a world that provided super-strong incentives for conflict narratives.

There’s this ritual in a daily newsroom where all the editors gather at 11 o’clock in the morning, and each of us writes a couple of sentences to describe the story we’re working on. They meet in a room over in the corner and decide whose story will be in the paper. And then, more importantly, for the sort of cultural cachet of what we do, who’s first going to be on the front page? It was the conflict stories that were always the ones that got on the front page; they were the ones that got the attention and were the ones that were incentivized.

I came to believe that this was a problem in newsroom culture, but it’s really drawn from a problem in the culture more broadly because that’s what audiences want. That’s what audiences respond to. We’ve really learned that in the last five years or more, as we’ve seen how conflict narratives incentivized by the AI algorithms of Facebook have just launched these conflicts to unimaginable disproportionate importance in our society. But I came from that culture of looking for conflict and crisis and tragedy narratives.

One of my editors had this saying which we used to laugh about, but which used to kind of get under my skin and bothered me, which was, ‘We don’t write about planes that don’t crash.’ And that’s true; we don’t. But if you really want to understand planes, you have to understand the fact that most of them don’t crash, and that’s an important thing for understanding planes.

Once I realized that these narratives of crisis and conflict weren’t the whole story, and in thinking about water, I began looking at how success had happened. I realized that this other really important narrative had kind of been squeezed out by this culture that I came from that motivated a particular style of thinking.

Once I got out of that, I really approached it with the zeal of the convert in terms of thinking about how these other narratives not only were more helpful to problem-solving, but also were far more dominant than I had realized, once I started looking for them. It’s certainly the case in Colorado River governance, where I spent most of my time, which overlaps some of the California issues Tracy and Tim talk about. California is the biggest user of Colorado River water in the West, but I think it spans a lot more geographies and areas.

So once I got that narrative, I worked with a really smart editor, Emily Turner at Island Press, who helped me think through this underlying insight that I had and how to then present that in the book. I realized that it was an entirely different and useful kind of storyline, and it animates now all the work that I do, both academically and in the writing that I do on water going forward.

LISA BEUTLER

There’s a definition of war. Tim, you’re an economist. Some of your fellow economists have written about understanding what the underpinning of war actually is. There have been two basic factors. One of them is at least one of the sides involved has to continue to expect that the gains from the conflict will outweigh the costs incurred. The other one is that there has to be a failure in bargaining so that, for some reason, there is an inability to reach a mutually advantageous, enforceable agreement.

Matthew Jackson and Massimo Morelli explain that understanding the why and the how of bargaining is really important because it’s going to tell you about the kind of war that’s going to emerge and how long the war will actually last. R.J. Rummel was a political scientist that spent his career studying war with a goal to help to resolve or eliminate them. He concluded that conflict ends when a new balance of powers has been determined. A new balance then means that both parties better perceive their mutual interests and are willing to live with whatever satisfaction of interests that results from the confrontation. I know these are actually ideas you’ve been studying. And I don’t know if it’s through this theory line, but you’ve been talking about this through your own language. So how did these worlds compare or contrast with your experience in the water world?

TIM QUINN

Both of those pieces you mentioned really resonate with me in the experience that I’ve had. If you look at the Jackson-Morelli argument, there’s always a tension between collaboration and adversarial decision-making. As I mentioned earlier, all negotiations are driven by their BATNAs (Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement). And the BATNAs have changed from one era of water management to another. In the development era, the BATNA was that you would get what you wanted through the adversarial process if you were the Metropolitan Water District in Southern California or the San Francisco water department.

In an earlier era, if you were a water agency and wanted to build a supply, you didn’t have to bargain, so you didn’t. And the result was very predictable. In the regulatory era, the reverse was true, with the regulators had very strong laws, and if they didn’t want to bargain, they didn’t have to. Again, the rules are changing now to where you do need to.

In an earlier era, if you were a water agency and wanted to build a supply, you didn’t have to bargain, so you didn’t. And the result was very predictable. In the regulatory era, the reverse was true, with the regulators had very strong laws, and if they didn’t want to bargain, they didn’t have to. Again, the rules are changing now to where you do need to.

The pivotal thing in my life was a good friend of mine who was the general manager of the Westlands Water District back in the 1990s. I’m a collaborationist at heart, even if not everybody agrees with that. I could see us going to war in 1992 over what became the Central Valley Project Improvement Act. And I was pleading with Jerry in a sidebar meeting at an ACWA Conference, why don’t we get Tom Graff and the other environmentalists and let’s negotiate this in California and avoid the mess of a war. I may have used the word war at the time in Washington, DC.

Jerry said something to me that I have never forgotten. He said, ‘Tim, you have to understand that people I work for (meaning his Board of Directors at Westlands). Some things can be negotiated away; some things have to be taken away.” That was a revolutionary moment for me. A key party was not going to negotiate in good faith. They had enjoyed the old development rules and didn’t appreciate that the rules and political competition were shifting. And I realized there would be no negotiating over CVPIA. And I became a warrior. I worked for Carl Boronkay. And Carl and Metropolitan were pivotal in passing the Central Valley Project Improvement Act. Since that time, we have been leveling the playing field in ways that I think agricultural is just starting to appreciate, although it took them a while.

It took a revolutionary change. It took war to have success in the early 1990s. The only time I think being a warrior ever promoted better policy was back in early 1992. And I’m sure there are lots of people out there disagreeing with me as I speak, but that’s my personal perspective.

In recent decades, we have leveled the playing field: winner takes all, adversarialism, top-down decision making simply will not work in a world where previously marginalized groups have access to the decision-making process. We keep trying to use the old top-down ways to make decisions. I think the Delta is the best example of that. They keep trying top-down managerial decision-making. I think their approach now with the voluntary agreements – that’s a step in the right direction. I don’t think it’s enough of a step, but it’s a step in the right direction.

We have had a lot of successes from collaborative decision-making in recent decades, which I wrote about in the paper, Forty Years of California Water Policy: What Worked, What Didn’t, and Lessons for the Future. There are the best management practices agreement in the early 1990s, which launched urban conservation as the backbone of urban water planning in the late 20th century – a truly historic thing. Drought water banks that I helped craft – we were looking at horrible adversarial action during the height of droughts. We avoided that in the early 90s by creating a voluntary collaborative, the drought water bank. That was followed by the Monterey amendments, which were controversial to some, but again, collaboration won over going to court. The Bay-Delta Accord in the mid-90s and even Cal Fed are among them.

We have had a lot of successes from collaborative decision-making in recent decades, which I wrote about in the paper, Forty Years of California Water Policy: What Worked, What Didn’t, and Lessons for the Future. There are the best management practices agreement in the early 1990s, which launched urban conservation as the backbone of urban water planning in the late 20th century – a truly historic thing. Drought water banks that I helped craft – we were looking at horrible adversarial action during the height of droughts. We avoided that in the early 90s by creating a voluntary collaborative, the drought water bank. That was followed by the Monterey amendments, which were controversial to some, but again, collaboration won over going to court. The Bay-Delta Accord in the mid-90s and even Cal Fed are among them.

When I wrote my paper, I was pretty despondent because I knew we needed to move into a collaborative era, and I didn’t see it happening out there. But collaboration, I would argue today, is blossoming in – of all places – the agricultural Central Valley of California. I would urge you to go to the Northern California Water Association’s website, norcalwater.org. I go to that website every couple of weeks because it makes me happy to know that progressive thinking is happening in California, in a place where it wasn’t 30 years ago.

In the San Joaquin Valley, I thought, frankly, we were doomed to more decades of conflict. That’s how we’ve always resolved things. But we’re now doing something called the CAP, the Collaborative Action Program, in which we have scores of people from all different sectors of water interests that are just realizing they need to work together instead of fighting each other.

I am very encouraged by that turn of events because war is not going to work anymore. War had its place. It definitely had its place. It built our system. It protected the environment. We made decisions through the adversarial process that were sometimes good, sometimes bad, but war is not going to get you where you need to go in the 21st century. You have to get to that collaborative era.

LISA BEUTLER

Tracy, you’ve got some really good lessons learned as well. You worked on the 2018 water efficiency legislation. Could you talk about what you’ve been hearing from the other panelists and how that compares or contrasts with your own successful efforts?

TRACY QUINN

To clarify my opening statements, I obviously support collaboration, and I think it is a great place to start. But it’s also a difficult place to start because you need clear rules and goals. And when you have diverse competing interests, it’s really difficult for a group to come together to coalesce around the same rules and goals. And that’s why a strong regulatory framework is so important for the agreements to be successful.

I think, unfortunately, with some of the agreements that we’ve seen in the past, there have been successful examples for some of the participants in there, but they haven’t been quite as successful for the environment. A lot of the agreements that we’ve made in California have resulted in greater diversions from the Delta. And as I said in my opening statement, we have fish populations that are plummeting. So I think going forward, it’s really important that the agreements are based on clear rules and goals, and have a bigger tent to make sure that community interests, tribal interests, the environment – all of those things are represented, so we’re meeting the needs of the broader community.

As far as the 2018 legislation that I worked on, many people may not be familiar with it. We had an epic drought in California between 2011 and 2016. During that time, the state was looking for tools to gauge how water suppliers were handling it. Do we have adequate supplies going forward? We didn’t really have any consistency around being able to report out on what our supplies look like and how well prepared we were. Many water suppliers had done a lot of great planning; they had really detailed water shortage contingency plans and lots of water and storage, but that wasn’t universal. Some water suppliers didn’t even have water shortage contingency plans; they didn’t have phases of how they would address deeper and deeper drought.

So the state started with voluntary conservation. They asked everyone to voluntarily save water and reduce water use by 20%. And as often happens, voluntary without the stick resulted in about an 8% reduction in demand statewide. The state then went to mandatory conservation, which got a lot of pushback, but it definitely highlighted the need for us to have longer-term conservation measures in place and a way to address the more intense and more frequent droughts that we know we’re going to see with climate change.

So a lot of stakeholders got together, including representatives from state agencies, the water supplier community, and the environmental organizations, and tried to come up with a new plan that would address the concerns of water suppliers from previous water efficiency efforts like 20×2020. Out of that effort and the mandatory reductions, suppliers said percent reductions just aren’t fair. It hurts early adopters of water efficiency programs, and it doesn’t take into consideration local conditions like climate, population, and how big the landscapes are in the neighborhoods. The result was a strategy to try to address these concerns with new customized water use targets that would include the state providing aerial imagery and landscape area measurements to each water supplier. That’s important and expensive data that water suppliers could use to improve water management within their service area.

So when the proposal came forward, and the water supplier community pretty much universally opposed it, it was really confusing for those of us who had worked on it. In theory, this addressed all of the concerns that we had heard repeatedly since 2009 throughout the drought. I was thinking, are they just fighting this because they don’t want to be regulated? Or are there real issues here that need to be addressed? My approach through that process is that I believe in open and honest communication, and I think that’s best achieved in one on one or small groups. I think it’s really important to get to know people. Through this process, I would have to say I made some really great friends and unlikely allies. I think you need to be honest and follow through with your promises, and through that process, you can build trust. And then lastly, keep focused on the long view.

Just because we’re being honest, there are also some challenges. There were people who mischaracterized the legislation. There were others that exaggerated some of the potential consequences. I understand that that can be a successful strategy, but it makes negotiations and finding common ground really difficult. But in the end, I found people that I believed I could trust to be honest with me as well. And we had really good conversations.

Just because we’re being honest, there are also some challenges. There were people who mischaracterized the legislation. There were others that exaggerated some of the potential consequences. I understand that that can be a successful strategy, but it makes negotiations and finding common ground really difficult. But in the end, I found people that I believed I could trust to be honest with me as well. And we had really good conversations.

Some of the things that the water suppliers asked for were changes that make a lot of sense, and I was happy to support them and their request to make those amendments to the bill. Others honestly made me really uncomfortable, because I felt like they compromised the integrity of what we were trying to achieve, at least in the short run. But I tried to put myself in their shoes. Unlike previous goals, which were a percentage reduction and very easy for the water suppliers to calculate, most of the water suppliers had no idea how their current water use compared to the water use target that they were going to be asked to comply with when this legislation passed. And I could see how that would make them uncomfortable. So I agreed to support changes to the bill, even though they made me uncomfortable because they were changes that made the water suppliers more comfortable with an enforceable set of standards with which they were going to have to comply. And I was hopeful that once we had more data and more information was made available through the implementation process, and suppliers were able to calculate their water use targets, that we could update the standards and make them more meaningful. And hopefully, the water suppliers would support that process as well.

In the end, we got a legislative package that wasn’t perfect. But we were able to get pretty broad support or at least eliminate a lot of the opposition for that package. And in the long run, this effort should help us understand how efficiently communities are using water, based on their local conditions, new technology, and a lot more information than they had before. It will provide new water management tools that otherwise wouldn’t have been available to water suppliers with fewer resources. And hopefully, it’ll advance water efficiency and help us to push off more GHG intensive new supplies. So I think all in all it was successful. I view it as a collaborative effort with some adversarial moments thrown in there. But we certainly achieved our goal. And now we’re in the tough part of the implementation.

LISA BEUTLER

While you’re talking, I was reminded that there are a couple of key principles in negotiation and conflict management. One of them is the importance of relationships, and that just cannot be understated. And then in this time of COVID, the fact that people don’t get to eat together – these are the kinds of things that typically really are the kinds of things that create relationships. It just changes the table.

You also talked about the importance of shuttle diplomacy and having the kinds of conversations that could be stacked, and people could be a little bit more candid. That speaks to the idea that many people live in two worlds: they’re living in the world at the table, and then they’re living in this external world where they have their own audiences and their own constituencies. It’s really an important, delicate balance and the people at the table have to understand that that dynamic. The last thing you said that I thought was so insightful and important is there’s always imperfect information and imperfect solutions. Perfect cannot be the enemy of the good, and that just moving the ball is important.

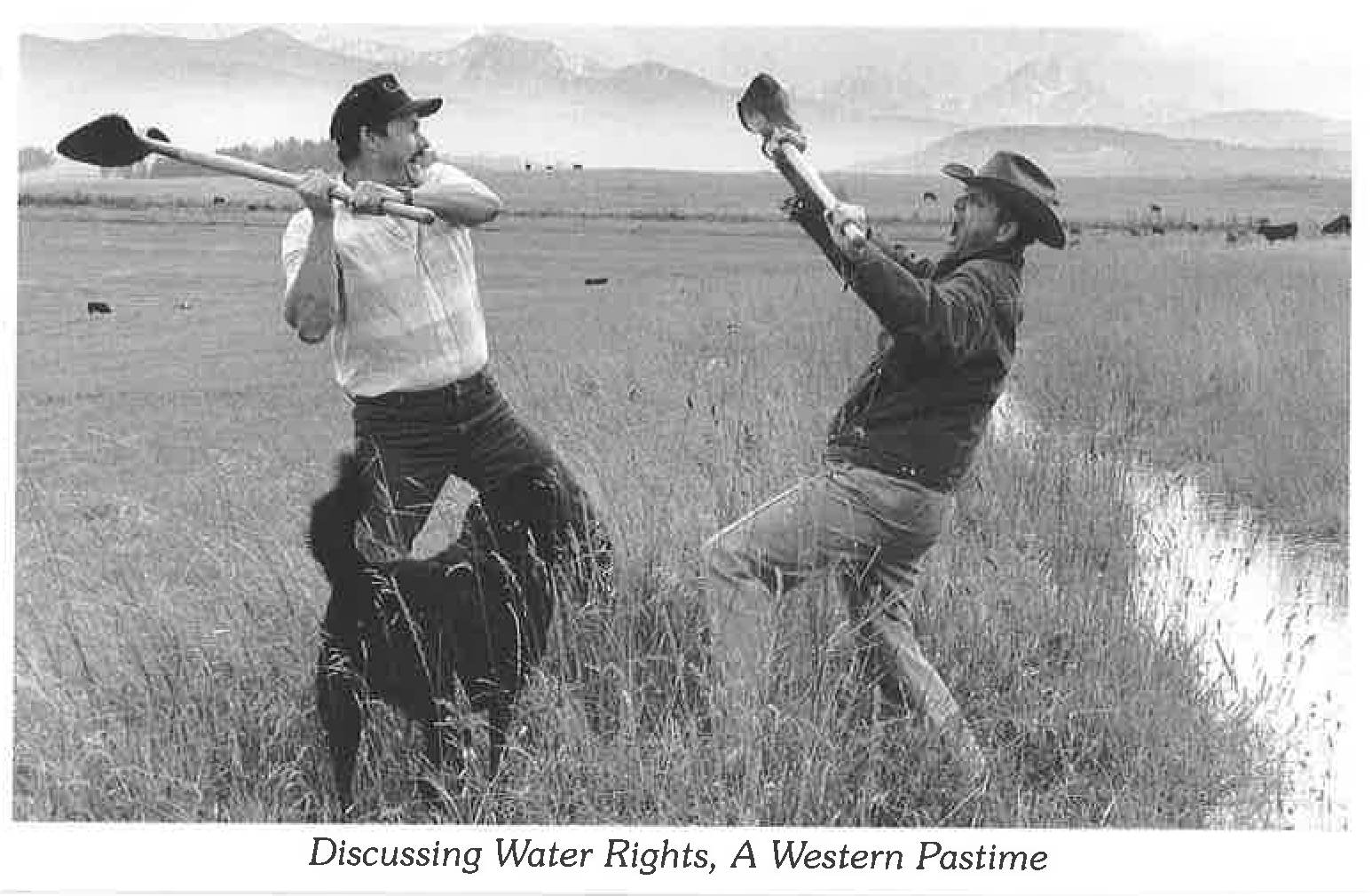

John, you’ve spent the last decade just dissecting politics and the realities of the Colorado River. And you’ve made some surprising and not surprising findings about the source of conflict and what people actually do to make things work. In your book, you throw in a lot of really good Western common water sayings. One of them that I loved was, ‘it’s better to be upstream with a shovel, then downstream was a decree.’ While we all share this great Western humor, Californians often don’t really appreciate the Colorado River. I’m in California, so I can say we always think of our own situations as unique. So how does your experience compare or contrast with what you’ve heard from Tim and Tracy? And what can you take from your work that would help them in their own efforts?

JOHN FLECK

I first met Tim more than ten years ago when I was on a fellowship at Stanford with the Water in the West and the Bill Lane Center. I was spending some time trying to understand the Sacramento Bay-Delta. And I threw up my hands, trying to figure out how to write about it because it was too Byzantine and too complex for me to understand what the narrative and the structure of the story might be. It remains a little bit impenetrable to me today as well.

I’m also a little hesitant in trying to think about how lessons from the Colorado River and the sort of optimistic success stories that I’ve talked about might apply in other places because each water problem’s geography, politics, hydrology, and social concerns are always unique. But there’s such an overlap in California that I think it’s really important that we draw these connections.

One of the real early insights into this came from a talk I heard Pat Mulroy give here in Albuquerque 10 years ago. She was the former head of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, one of the leaders of the conflict transitioning into the collaborative governance processes in the Colorado River Basin. She pointed out the interconnections between the Bay-Delta through the State Water Project, to Southern California to Metropolitan, drawing off the Colorado River, which flows down past my neighborhood and brings water and the inner connection between me here in Albuquerque, and in you all in the Sacramento-Bay Delta 1000 miles away. We’ve created this one giant interconnected human-created super-watershed across the West. And so we better understand how to make the whole thing function effectively in this interconnected way.

That was really important for me in thinking about how all these pieces have to fit together, because what we have in the Colorado River Basin, some folks out in California dealing with the pains of the agonies of the Sacramento Bay Delta over these many, many years, may not fully appreciate it. We’ve built an effective system that has provided an evolving structure of collaborative governance that goes back a century now in the Colorado River Basin, which is really the effective story of collaboration that I describe in the book, Water is for Fighting Over: and other Myths About Water in the West

That was really important for me in thinking about how all these pieces have to fit together, because what we have in the Colorado River Basin, some folks out in California dealing with the pains of the agonies of the Sacramento Bay Delta over these many, many years, may not fully appreciate it. We’ve built an effective system that has provided an evolving structure of collaborative governance that goes back a century now in the Colorado River Basin, which is really the effective story of collaboration that I describe in the book, Water is for Fighting Over: and other Myths About Water in the West

One of the things that I didn’t fully appreciate when I published that book that I’ve really come to appreciate in a much greater way in the years since goes back to a point Tim made that collaboration is a direct partner with conflict. Collaboration grows out of the challenge of conflict and overcoming it.

When Island Press published a paperback edition of Water is for Fighting Over a couple of years after the hardback edition came out at the end of 2016, there was some really difficult conflict underway in the Colorado River Basin over a new set of agreements we called the Drought Contingency Plan. And there was the sense, especially in the state of Arizona, that conflict was overcoming collaboration, and there was a sense of the wheels were going to come off. My optimistic narrative was going to look really dumb. And it’s published in a physical book, so you’re stuck with it; there’s no way to change it.

I was talking to a lot of my friends working on the Colorado River. And I kept posing this rhetorical question to them, what am I – optimistic or pessimistic? One of my friends who had many years of working on the river as a very effective collaborator, we were at the happy hour after a day’s meetings, and she stared me really intensely in the eye and said, John, you have to be optimistic. Not meaning that optimism was right, but that somebody needs to model the optimistic path.

And I think that’s what’s really important about what Tim is trying to do here. For example, with SGMA in the Central Valley, it’s not that successful collaboration is guaranteed, but that as we are thinking about how to solve these problems, those of us who have these public platforms like the three of us on this panel – we all have these public positions. We have to model the optimistic path.

One of the points I made in Water is for Fighting Over is that if we allow our rhetoric to just descend into the expectation of conflict, then that’s what we’re going to get. Collaboration is not assured; collaborative success is not assured. But we have to model that as an effective path. Because the alternative, I think, is really bad. And I don’t want to see that happen.

LISA BEUTLER

I’m going to jump to the question about thinking about words differently. So Mike Antos started this discussion with the idea that hearing the word ‘war’ actually is very problematic as it creates a mindset that was not as useful as it needs to be.

So what I wanted to do was talk a little bit about some of the things that we heard when we even posed this webinar. We heard from a combat veteran who wrote us a note and said, ‘I’m glad you’re talking about this because I work in water, and I have gone to war. And I’m really uncomfortable with this framing.’ I had another blogger write a note to me and say, ‘If it’s a war, who are the sides? Who is paying the cost? Who are the combatants? And who are the civilians? Do we have the equivalent of women and children?’

There’s a ton of research on the fact that problem-solving and conflict resolution, that solution proposing – telling other people, ‘I know what you need,’ that that actually can be more of a problem, when people might actually have common ground what the issue is, but they don’t like the way that you’re telling them what the solutions are.

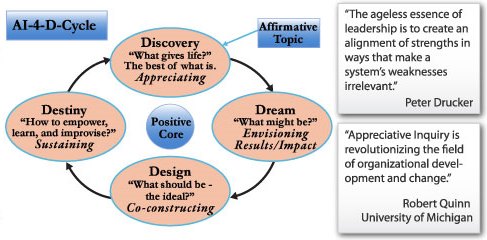

Another interesting theory that’s evolved out of the conflict world and general organizational theory has to do with some of the work that David Cooperrider has done at Case Western. It’s called appreciative inquiry. What he talks about is that our words create the worlds that we live in. So if we are actually using those words, we’re setting the stage. Our inquiry will make a change, so the act of questioning anything will change it. We can choose the things that we study. So the principle there is the things we pay attention to, the things we measure, the things we get, and images inspire action. So if we can begin to visualize the context of success versus the context of conflict, that can also inspire action. And then finally, positive questions, they lead to positive change. So that’s kind of the theory base.

Another interesting theory that’s evolved out of the conflict world and general organizational theory has to do with some of the work that David Cooperrider has done at Case Western. It’s called appreciative inquiry. What he talks about is that our words create the worlds that we live in. So if we are actually using those words, we’re setting the stage. Our inquiry will make a change, so the act of questioning anything will change it. We can choose the things that we study. So the principle there is the things we pay attention to, the things we measure, the things we get, and images inspire action. So if we can begin to visualize the context of success versus the context of conflict, that can also inspire action. And then finally, positive questions, they lead to positive change. So that’s kind of the theory base.

At the heart of his theories, any negative frame of fixing the broken is an unhelpful frame. And in fact, with water, there’s no such thing as fixing water. Water is a continuously evolving situation; nature is not a fixed or a static thing. So to all of you, can we stop the war language? Is there a way to reframe what is happening to get a better outcome?

JOHN FLECK

That’s what I tried to do in the book and what I now try to do with the bully pulpit that the publication of that book got me. I’m the guy who says Mark Twain didn’t say it, and it’s probably a bad metaphor anyway. One of the things I learned in my journalism career is that no one story solves a problem. No one story draws the attention; what draws the attention is the repetition. Just pointing out repeatedly, that’s not a war, that’s not a conflict, and there’s another way of framing this issue, I think, is an incredibly valuable step. And it’s certainly as an academic guy writes books now; that’s the vantage point I have in the place that I can do this work from.

TRACY QUINN

What you said – Will anyone be killed? How is this a war? I would say that, on a personal level, there are definitely times when this feels like a war, because there are huge consequences for mistakes. Even in preparation for this panel, I thought that I have to be careful not to misstate anything or use the wrong statistic or the wrong verbiage for fear that someone on the “other side” will use it against me, questioning my knowledge or my integrity.

When I’m out there doing advocacy, it sometimes feels the same way. I won’t be killed, but the policy that I’m advocating for could be, my reputation could be, so sometimes it feels like there are really high stakes personally. Then obviously, high stakes for the people and wildlife that depend on water in California. So I think that because the stakes are so high, it raises the level of conflict.

How do we move forward and address and change that dynamic? I think, in the larger sense, we need to start by exploring how water issues are framed in California. As always, North versus South, rural versus urban, fish versus farm- these are oversimplifications that aren’t accurate, and they only serve to reinforce these outdated adversarial mindsets.

One of the things that I’ve found to be helpful is to try to have open and honest discussions about motivations and approaches with my fellow stakeholders. So maybe it’s helpful to start by sharing some of NRDC’s relation to the Delta, which is the center of water conflict in California for probably at least my lifetime, and the framing of this fish versus farm.

So with the caveat that I have not been deeply engaged in NRDC’s Delta work, and this is simply coming from my time is working in water for the last 20 year: In the Delta, when NRDC advocates for reduced diversions and keeping water in storage, we aren’t simply looking to protect an endangered fish without concern for the impacts to other interests that are also dependent on that water. Our goal is to find solutions that are good for the environment, the economy, and the impacted communities.

So, for example, the Delta smelt is an indicator of a healthy ecosystem. Thousands of fishing jobs and farmers in the Delta depend on that healthy ecosystem. So we’re also advocating for the livelihoods of professional and subsistence fishermen and farmers when we advocate for increased flows. Those flows help fish survival, help curb harmful algal blooms that threaten public health, a desirable waterfront economy, Delta wildlife, pets, and the extensive homeless community that living adjacent to those waterways.

So, for example, the Delta smelt is an indicator of a healthy ecosystem. Thousands of fishing jobs and farmers in the Delta depend on that healthy ecosystem. So we’re also advocating for the livelihoods of professional and subsistence fishermen and farmers when we advocate for increased flows. Those flows help fish survival, help curb harmful algal blooms that threaten public health, a desirable waterfront economy, Delta wildlife, pets, and the extensive homeless community that living adjacent to those waterways.

Requiring more water to be held in storage helps preserve cold temperatures for salmon and improves drought preparedness by ensuring that we have additional water available, should we have a dry period the following year. And we’re not working on reducing diversions in a silo. We’re also working on supportive policies that will help make those reductions easier, including funding to help sustain the economy and a healthy water supply system.

I lead our work to advance water efficiency and promote water recycling. My team also works to improve stormwater capture. We were instrumental in the passage of measure W here in Los Angeles, which is a parcel tax that provides funding for stormwater capture projects. And we have a team that advocates for financial incentives for agricultural practices that promote healthy soil and drought protection and help farmers maintain production rates with less supplemental irrigation.

California is a large and diverse state with several competing interests for one shared resource that is becoming more and more scarce. Of course, there’s going to be conflict, but we don’t need to try to conquer one another. We should focus on solutions that can, directly and indirectly, benefit multiple competing interests. One of those things is diversifying our water supply portfolio; I think that’s something that we can and should all get behind.

TIM QUINN

I agree that words matter. I agree that we need to separate the words water and war from each other. And but in doing so, don’t lose sight of the fact that those two words belonged together for most of California’s water history. We did engage in warfare.

I like your dictionary definition of war, which comes down to adversarial decision-making in which there are winners and losers. That’s the heart of an adversarial process, and in my mind, I equate it to warfare. But we did that on both sides; we created collateral damage.

One of the things I realized is everybody feels like they’ve been victimized: the farmers feel like they’ve been victimized, the environmentalists feel like they’ve been victimized, the drinking water activists feel like they’ve been victimized – and they are all correct. Because at various times, they have wound up on the losing side.

So we need to separate those two words. And I think the best way to do it is by making people understand, that is how we got things done in the past, but it is not going to work in the future. How do we work into a collaborative era together, where we truly have multiple benefits, and open and transparent processes? In my heart of hearts, war is easy; collaboration is hell – don’t ever forget that because collaboration is not easy. We need to focus on the future, but I only think we can do that successfully if we don’t forget the past.

MIKE ANTOS

We’ve heard from folks in the questions about Cal Fed, SGMA, and the Integrated Regional Water Management Program in California. All three of those were efforts to administer collaborative processes, so is legislation or programs that try to bring people together to achieve these collaborative solutions – is it either the stick or carrot drive collaboratives? I’m curious if the panelists are willing to accept that those three things are of a like kind and talk about the tools that we’ve brought to bear to help push these collaboratives and talk about how governance and policy can help make these things happen better.

TIM QUINN

I do think they all have that common feature, but I think a lot of people think Cal Fed was not a success. I was up to my eyeballs in Cal Fed, and I believe Cal Fed changed a lot. I was still at Metropolitan in those days, and Cal Fed was where we realized that completing the State Water Project was not our future; local resource development, efficiencies, recycling – that was our future. We learned that as we were going through the Cal Fed process. I think Cal Fed had success after success after success – until it got to the Delta. And in the Delta, there are a thousand reasons, but a big chunk of it was that the state and federal agencies weren’t ready for the kind of thinking back then that they needed to be into. We were headed in that direction in the 1990s, with leadership change and collaboration dying on the vine.

It’s the same thing with SGMA. I was one of the major architects of SGMA. Frankly, I think SGMA wouldn’t have happened if Tim Quinn hadn’t worked for seven years to change his board of directors’ mind about what needed to happen with respect to groundwater. In my mind, SGMA was all about governance. In the past, the local water managers knew they had a problem. If you couldn’t come to an agreement, the default was to keep on pumping. SGMA changed the default. If you don’t come to an agreement, it’s ‘Hello, State Water Resources Control Board’ instead of keep on pumping.

It’s the same thing with SGMA. I was one of the major architects of SGMA. Frankly, I think SGMA wouldn’t have happened if Tim Quinn hadn’t worked for seven years to change his board of directors’ mind about what needed to happen with respect to groundwater. In my mind, SGMA was all about governance. In the past, the local water managers knew they had a problem. If you couldn’t come to an agreement, the default was to keep on pumping. SGMA changed the default. If you don’t come to an agreement, it’s ‘Hello, State Water Resources Control Board’ instead of keep on pumping.

What’s going on with SGMA is a remarkable change. I’m pleased; it’s certainly not perfect, miles from perfect, but we also set up an iterative process between the state agencies and the local decision-makers. It’s currently one of the things that people are complaining about in GSPs and GSAs – those things are very imperfect now, but we have an iterative process in which DWR and the State Board have the opportunity to work collaboratively with those local decision-makers.

I think over time, you will see many of the defects that are in the current groundwater sustainability plans; they will evolve over time because they’re doing things inconsistent with definitions of sustainability in the law. And I think in their heart of hearts, they really want to do the right thing. It’s going to take them a while working with other interests to get there.

MIKE ANTOS

One of the most upvoted questions we have at the moment is the assembly bill that was passed a number of years ago in California that recognizes the source watersheds of the Sierra as integral components of California’s water infrastructure, or the idea of making natural space and watersheds into infrastructure such that you can invest in it and prioritize it. There are also lots of conversations about the Upper and Lower Colorado situation. So in this question of suggesting that upper and lower watershed are shared infrastructure, whether it’s a natural system or not, and the idea of natural space as infrastructure such that it can be invested in like infrastructure – I suppose it’s probably not fair to match the upper and lower Colorado to the upper and lower of the Sierra, but perhaps we can pull it off. What do you think, John? Can we talk about the watershed as infrastructure as a platform for investment, as a way for the lower users to recognize the upper supply source?

One of the most upvoted questions we have at the moment is the assembly bill that was passed a number of years ago in California that recognizes the source watersheds of the Sierra as integral components of California’s water infrastructure, or the idea of making natural space and watersheds into infrastructure such that you can invest in it and prioritize it. There are also lots of conversations about the Upper and Lower Colorado situation. So in this question of suggesting that upper and lower watershed are shared infrastructure, whether it’s a natural system or not, and the idea of natural space as infrastructure such that it can be invested in like infrastructure – I suppose it’s probably not fair to match the upper and lower Colorado to the upper and lower of the Sierra, but perhaps we can pull it off. What do you think, John? Can we talk about the watershed as infrastructure as a platform for investment, as a way for the lower users to recognize the upper supply source?

JOHN FLECK

I have a couple of things to say here. One is that, in some sense, the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basin matching doesn’t quite work. But this is something that we’ve been thinking about here in the Rio Grande as well. I’m in Albuquerque, and we use Colorado River water through transbasin diversion, but we’re in the Rio Grande basin. And we’ve had some folks here, led by the Nature Conservancy, who have been really working really hard to build broad collaborative scale governance structures to implement exactly this thing. I don’t think we can call it a success yet, but I think we can call it a success in that they have fostered this really significant conversation with my local utility contributing to that. We also see this happening in a number of other places around the West, such as the Salt River Project and greater Phoenix area, especially with the watersheds of the Salt and Verde rivers that bring a big chunk of Central Arizona’s water that doesn’t come from the main stem of the Colorado River. So I think those integrations matter.

It also raises this broader question of the importance of successful collaboration in thinking about where we’re drawing the boundaries around the resource system when we have these conversations. We often have the tendencies to draw them narrowly because as soon as you draw the sort of geographic boundary around the water problem you’re trying to solve more broadly, there are more stakeholders and more interest involved. You get this exponential growth in the difficulties of the conversation. But if you don’t extend either to headwaters and forested watersheds and mountains or to upstream neighbors, as we have to worry about here in the Rio Grande with water flowing down from the state of Colorado, for example, then our collaboration can fall short because we don’t have the right interested parties in the discussion.

This is really important … Elinor Ostrom, the late social scientist who helped us think about how these collaborative structures function in practice, talked about the importance of this – let’s look carefully at where we’ve drawn the boundaries and how our system of collaboration interacts across those boundaries.

TIM QUINN

I couldn’t agree more … I saw recently on the Northern California Water Association’s website, ‘From the mountain ridge down to the river mouth.’ I tend to think ‘Peak to Pacific’ – that deals with half the California anyway. It’s just hugely important.

When I worked at ACWA, several of my board members were from that part of California. They strongly felt that what happened up in their neck of the woods should be paid attention to by people who use water closer to sea level. And I couldn’t have agreed more. I helped them work with the ACWA board, and when I left, it was one of the highest priorities in the ACWA board’s strategic plan. It was really something that resonated with me. I know my successor, Dave Eggerton, used to manage water agencies up in the upper watershed. And he has continued that work. So at least with respect to ACWA, it’s an organization that can knit together people from the southern California Coastal Plains, the Bay Area, coastal Central Valley, and people in the natural resources up in the upper watershed.

One of the things we need to focus on the most as we move towards infrastructure legislation in Washington DC is making sure that that that legislation recognizes the value of natural infrastructure and gives us the resources to invest in it.

MIKE ANTOS

There are questions about the moment of racial equity that we’ve been going through in the United States for the last year or so after the prominent deaths of black Americans. And the question is, how do we start thinking about white privilege in these traditional governance and environmental management spaces that we all work within? And then how do we bring racial equity and other forms of equity into the work that we do? And I know this is a little to the side of what we’ve been discussing, but maybe this is a central piece that we need to bring in. So Tracy, why don’t you go first because they called you out, but I suspect everyone has something to say here.

TRACY QUINN

I’m so glad that this was brought up. I think that we are at a reckoning point. You can’t work in the environment and can’t work on water without considering the disparate impacts of pollution and access and affordability on communities of color. We look at Cal EnviroScreen and overlay the demographics of our state, and you can see that communities of color are disproporti

onately impacted by all aspects around water and aren’t represented at the tables that are making the decisions about the solutions for those problems. Even within my own organization, we are a very white organization. And this is something that we are reckoning with internally – environmental justice and social justice.

We need to make sure that the impacted communities have a voice at the table. John spoke to this, Tim spoke to this – the right people have to be at the table. We need to make sure that we are centering communities that are being impacted by these policies and making sure that they have a seat at the table and that they’re driving the solutions that are going to be impacted in their communities. So, I think that it is really important.

I think it’s a really important issue, and it should be centered around all of our conversations. Even as I was preparing for this panel, it occurred to me that all of us are white. For this conversation, there would have been an advantage to having a more diverse panel to have this conversation. And I hope that the next conversation on this topic or any future topics is, you know, that we’re able to have a more diverse panel.

TIM QUINN

We have a long way to go. I was the head of this Association of California Water Agencies for 11 years. Go to any ACWA conference, and you’d see a sea of pretty much white faces. We need to change that, and I believe it will change. Because as I said in my remarks, water policy is becoming more and more participatory. A few years ago, we passed [the human right to water legislation.] That was it. These previously marginalized groups said we’re tired of being marginalized, and they got that legislation passed.

I can tell you, in the Collaborative Action Program that we’re building in the San Joaquin Valley, those groups are at our table, and they are being respected, and we listen with empathy at our table. Again, we’ve got a long way to go. I’m not saying everything is right by any stretch of the imagination. But one of the things I’m spending a fair amount of time on right now is raising money for those groups or helping them raise money so that they can have the resources and the capacity to meaningfully influence politics. And that’s not something that I would have been doing ten years ago.

JOHN FLECK

That segues nicely into the broader point I wanted to make. In my work now at the University of New Mexico, I’m the director of the water resources program. I work with graduate students and also colleagues. We’ve been doing some really interesting work with a really smart young economist in our department, Benjamin Jones, who looks at the value of trees, and in particular, at the health benefits the community gets by having trees. I used to be one of those water conservation nuts who thought, oh, good, we have fewer trees in our neighborhood, so we’re conserving water. And Benjamin has helped me understand that I was missing the value being provided by those trees. So we looked at the value of trees. And Benjamin is very clever about helping us measure that. And we can see that there are these health benefits that a neighborhood gets by having trees. Well, if you look at the distribution of trees around Albuquerque, which some of my students are looking at now, you find who has the trees, right? It’s the affluent neighborhoods. There’s a reason the cliche of the leafy neighborhood exists.

So it points to a place where, at least in my mind, that we as a community may have drawn the boundaries around what we’re considering the water policy problem in a way that ignores these disadvantaged communities, economically, socioeconomically, ethnically – that don’t have the trees. So if we want to think about the optimal distribution of water across our landscape, which is what Benjamin does as a math problem, we can say we should give those poor folks some trees. But as long as we don’t have a water policy apparatus capable of thinking that through, we’re not going to come up with good solutions.

So it points to a place where, at least in my mind, that we as a community may have drawn the boundaries around what we’re considering the water policy problem in a way that ignores these disadvantaged communities, economically, socioeconomically, ethnically – that don’t have the trees. So if we want to think about the optimal distribution of water across our landscape, which is what Benjamin does as a math problem, we can say we should give those poor folks some trees. But as long as we don’t have a water policy apparatus capable of thinking that through, we’re not going to come up with good solutions.

And that leads me to this broader point. I wrote a whole chapter in Water is for Fighting Over but in preparation for this panel, and I went back and looked at this chapter, and I think it’s a thing that needs to be more centrally considered as we think about going forward with the broad collaborative governance solutions that we’re interested in. Which is, in these collaborative structures, even if we are successful in collaboration, who is it who’s still not in the room, participating in the collaboration? Who is not there?

We’ve been really successful in the collaboration in the Colorado River Basin in solving some problems. We’ve figured out how to crack the door open a little bit to let some environmental groups into the room sometimes, and their voices are heard. And when they are allowed to contribute to the solutions, the solutions are better.

But we have a huge problem in the Colorado River Basin right now with Native American communities with tribal interests that have legal and moral rights to some water that they’re not yet using. There is a great deal of difficulty in solving that problem without recognizing the reality that if a tribe uses more water and that pool of available water is shrinking, that means less water for other people. And so, figuring out how to enable that collaboration is one of the really hard problems that we face going forward. That’s my central hope, as optimistic as I am about collaboration. I’m still nervous about this piece. I think we need to be thoughtful and mindful about figuring out how to solve this piece of the problem as our collaboration is going forward. Let’s look around when we’re in the room collaborating at those who are not there.

TIM QUINN

I’m an economist by training. In my Ph.D. dissertation 40 years ago, I started thinking and still do think about the world as politics and marketers because that’s how you analyze the world. In the political marketplace, things happen because people and interest groups join together; they build coalitions to make things happen. Private markets go with shifts in demand and supply. Political markets go with shifts in coalition building. And we need to keep building broader coalitions to push leadership in the direction of realizing that they have to support collaborative decision-making.

When they did that, in the Clinton-Pete Wilson era, it wasn’t perfect, but we made a lot of progress with collaboration. And then leadership lost the interest, and the warriors took over. And collaboration, at least outside the legislature – we had a lot of success in the legislature, but the kind of thing that was happening in the 90s stopped happening. And we need to get back in the habit of doing that by working together whenever we can.

TRACY QUINN

John said a lot of the things that I had planned to say as far as making sure that the right people are at the table. And I think Tim gave a really eloquent closing. So maybe I’ll just end with … I pursued a career in advocacy because I liked competition. I was an athlete my whole life. And I thought that a career at NRDC would be .. I wanted to win. I didn’t see other stakeholders as people with interests with valid points, you know, they were my competition, and I was going to crush them.

I think what I’ve learned in practice is that we can get a lot further together. And I’ve learned a lot from the people that were propped up as my enemies, and many of them have turned into friends, hopefully, lifelong friends. I am optimistic. I hope that we can model some optimism here and throughout our continued careers. I am optimistic about the importance of collaboration in the ecosystem where each of the litigation and regulatory frameworks all play a role, but strong collaboration, I think, is the future, and I look forward to working with all of you in collaborative ways going forward.

LISA BEUTLER

When you told that story, it reminded me a years ago, I was in a really, really contentious, collaborative process. And it was brutal. We had been in it for about a year, and one day one of the stakeholders looked at another stakeholder and said, ‘Listen, we’ve just got to get along because let’s face it; eventually our children are going to get married and then we’re going to be in-laws, so we need to figure it out.’ You said this so beautifully before about the whole idea of relationships. So thank you so much.

MIKE ANTOS

This has been extraordinary – from a Saturday afternoon snark out into the Twitterverse to this just really amazing discussion with so much engagement from the folks that came. I’m so appreciative that things like this can happen amongst the colleagues that we all have together. The relationships that brought this into being where the three of you have been talking, and a whole bunch of people have been listening and asking questions; I think it’s an extraordinary sign that a lot of us are modeling this optimistic path.

I was thinking, Tracy, as you were talking about your sports experience, this idea that’s out there about the difference between a finite game and an infinite one. A finite game is for the purpose of winning; it is zero-sum; somebody wins and somebody loses. The idea of an infinite game is that its purpose is that you get to continue to play. And what’s different between war and sport is that the victor in a sporting match gets a chance to play that same opponent again, sometime in the future. And that idea that sometimes we are opponents, perhaps sometimes colleagues, I think that’s just a really a neat way to be thinking about it – that you can’t be your best if you don’t have someone to test yourself against.

It was fun watching everybody in the Q&A start to catch the words that we use. Now you’re playing my game. ‘In the trenches’ was mentioned; someone else suggested that ‘we are talking softly and carrying a big stick.’ I think we have a long way to go to recognize how we’ve allowed war and violence to pervade our language. And it’s something that I hope everyone has a little hiccup going forward as they travel their water world, and you hear the wars, and you hear the trenches and the fight, and the girding for battle – realize that those words are impacting us in ways perhaps we don’t realize and we should abandon them. We should also make sure that we can fight back against the copy editors responsible for the headlines and get them to quit doing it.

So that’s my closing. Thank you so much, everyone.