Presentation covers the preliminary cost estimate, the preliminary benefits analysis, the agreement in principle for the State Water Project Delta conveyance contract amendment and how opting out will work, and the funding agreements

In December, the Metropolitan Water District Board of Directors will be asked to support a motion to fund a portion of the planning costs for the Delta Conveyance Project. In preparation for the upcoming vote, staff began a series of presentations for the Special Committee on the Bay-Delta to prepare the directors for the vote.

In this presentation, Mr. Arakawa discussed the preliminary cost estimate, the preliminary benefits analysis, the agreement in principle, the funding agreements, the activities of the Design and Construction Authority and the Stakeholder Engagement Committee, and next steps. At the October meeting, they will discuss the Design and Construction Authority agreement and any questions that come up from today’s presentation that need further discussion, and in November, they will discuss the board action.

In this presentation, Mr. Arakawa discussed the preliminary cost estimate, the preliminary benefits analysis, the agreement in principle, the funding agreements, the activities of the Design and Construction Authority and the Stakeholder Engagement Committee, and next steps. At the October meeting, they will discuss the Design and Construction Authority agreement and any questions that come up from today’s presentation that need further discussion, and in November, they will discuss the board action.

In December, the Metropolitan Board of Directors will consider a funding request for a portion of the project planning costs, consider the agreement in principle for the contract extension that has been negotiated between the State Water Project contractors and the Department of Water Resources, and potential updates to the Design and Construction Authority agreement.

Metropolitan’s vote on project participation will likely come sometime in 2024 or later, but prior to that, there are many other permits and decisions to occur.

The slide shows the latest schedule for the Delta Conveyance Project. Currently, they are working on the CEQA/NEPA review and preparing the administrative draft of the environmental impact report. A public review draft is expected to be ready for public comment in 2022, with a final environmental impact report in the second half of 2023. Other efforts listed include the endangered species consultations on both federal and state Endangered Species Act which will occur during 2023, and the water rights decision at the State Water Board and the consistency determination with the Delta Stewardship Council’s Delta Plan occurring farther out in 2024.

The slide shows the latest schedule for the Delta Conveyance Project. Currently, they are working on the CEQA/NEPA review and preparing the administrative draft of the environmental impact report. A public review draft is expected to be ready for public comment in 2022, with a final environmental impact report in the second half of 2023. Other efforts listed include the endangered species consultations on both federal and state Endangered Species Act which will occur during 2023, and the water rights decision at the State Water Board and the consistency determination with the Delta Stewardship Council’s Delta Plan occurring farther out in 2024.

PRELIMINARY COSTS

Mr. Arakawa then turned to the preliminary cost estimates, emphasizing that it is very early in the planning process. There is no draft EIR and no alternatives analyzed as of yet. There is only the scoping effort that the Department of Water Resources initiated earlier this year which gave a very basic description of the facilities. Those facilities include one tunnel at 6000 cfs, two intakes, 42 miles of tunnel, and associated appurtenance facilities such as a pumping station and a forebay.

Mr. Arakawa then turned to the preliminary cost estimates, emphasizing that it is very early in the planning process. There is no draft EIR and no alternatives analyzed as of yet. There is only the scoping effort that the Department of Water Resources initiated earlier this year which gave a very basic description of the facilities. Those facilities include one tunnel at 6000 cfs, two intakes, 42 miles of tunnel, and associated appurtenance facilities such as a pumping station and a forebay.

“We’re far ahead of any kind of refined level project,” said Mr. Arakawa. “We haven’t gone through the environmental process, and in fact, there’s no conceptual engineering report, but for purposes of giving the water contracting agencies or the public water agencies a basis for talking to their boards, the DCA performed some cost assessments to take into account the facilities that included in the footprint.”

The preliminary cost estimate is $15.9 billion dollars, which includes the construction costs, the management costs, the planning costs, oversight by DWR, and assumptions about contingencies and mitigation. The estimate is in 2020 dollars, which means it doesn’t take into account any escalation of costs during the construction period or anything like that, he explained.

The preliminary cost estimate is $15.9 billion dollars, which includes the construction costs, the management costs, the planning costs, oversight by DWR, and assumptions about contingencies and mitigation. The estimate is in 2020 dollars, which means it doesn’t take into account any escalation of costs during the construction period or anything like that, he explained.

“That’s if you were to build it today with today’s dollars, with the scope of the project that has been defined to date.”

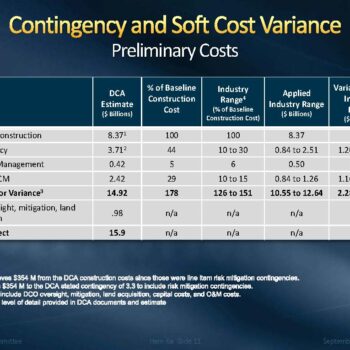

Mr. Arakawa then explained that there are a number of different components in the cost estimate, such as construction, management, and mitigation that all adds up to the total cost. Each component has a level of contingency that should be included in any cost estimates. When assigning contingencies, one takes into account where the project is in the planning process, the amount of information you have such as geotechnical or other foundational information, and the project definition, and one derives from that what type of management costs can be expected and what kind of contingencies need to be considered.

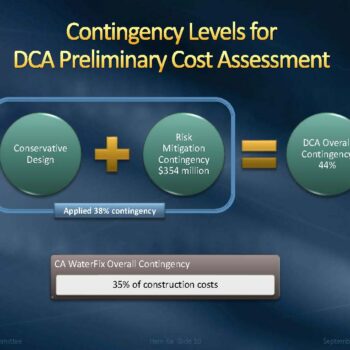

“The DCA cost assessment includes three levels of a conservative estimate, whereas Cal Water Fix, when that estimate was made, we were far along in the planning process and there was one level of contingency,” he said. “There’s no right way or wrong way; we’re just pointing out how this was all done. With the DCA, they looked at a conservative design, taking into account uncertainties with regards to the facilities, and the conditions in the Delta with the geotechnical information that’s available. They took into account risks that the project would have and what type of costs to mitigate those risks, and then in addition to that, they applied a contingency to all of that in order to come up with the overall cost estimate of $15.9 billion. So embedded in that is a total contingency.”

“The DCA started with a conservative design, based on the information that they have, then added the estimate for risk and mitigation,” he said. “In the case of the DCA’s work, they estimated that to be at $354 million to mitigate those risks. Then they applied a 38% contingency to each of those and that results in the overall contingency for the DCA cost assessment. So the way we’re analyzing it is that the $15.9 billion has an overall contingency of about 44% when you consider all of these three aspects: the conservative design, the risk contingency, mitigation contingency, and the overall contingency. The Cal Water Fix had a 35% cost contingency for that project.”

Mr. Arakawa presented the slide with table acknowledging it has a lot of numbers. “The left column just describes the key components. You have the construction, you have the contingency, you have program management, and you have design and construction management, and then below that, there is DWR oversight, mitigation, land acquisition, that all totals up to $15.9 billion dollars.”

Staff received some analysis and help from the engineering group at Metropolitan that helped them understand the context of this cost estimate. “What our experts helped us understand is that when you look at the industry process and the industry range, depending upon program management, design and construction management, or contingency, there’s a range you ought to be looking at,” he said. “The experts looked at the range of 10 to 30% contingency, they looked at for design and construction management 10 to 15%, so that’s all under that industry range column, and then when you apply that range, you have the second to the last column, which is in billions of dollars. You use the $8.37 billion in construction costs, you apply those industry ranges, and you can come up with what a range of cost might be for those elements, for contingency, program management, and design and construction management, based on that industry range.”

“We wanted to get a feel or sensitivity for how to think about the $15.9 billion, and the conclusion that we’ve drawn is that is its work that was done very thoroughly and that depending upon what type of information we get from further work, that may affect the level of contingency that will be utilized because of the range of knowns and unknowns, and therefore that last column gives you a variance that you can think about when talking about the total cost of the project. On the low end, it might have a variance, that $15.9 might have a variance from the industry standard of 2.28 or it may have a high end at 4.37. I don’t think it’s really important to get hung up in the specific numbers there, other than to understand that this is using knowledge from expertise that’s evolved in a lot of different projects, using industry standards, and it gives you some context of how to think about this initial proposed cost estimate or cost assessment.”

PRELIMINARY BENEFITS

Mr. Arakawa next turned to the preliminary benefits analysis, which is likewise highly preliminary as the project has not completed the environmental or endangered species processes. “But overall we know that the project as scoped by the state, in the state’s communication and the governor’s statement, has aspects of climate resiliency, seismic resiliency, and reliability,” he said.

“Really what’s involved in the purpose of the Delta conveyance project is to be able to protect the State Water Project, to address climate change, to address weather changes, rising sea levels, to be able to deal with the seismic risks that are in the Delta as a result earthquake faults that are near or in the Delta, to be able to adjust to regulations both that we have today as well as future regulations, and to have a project that is capable of adapting and still protecting the environment and having reliable water supplies. These are not new things, these are things that are established in the project’s purpose as the state has pursued the project under the environmental process.”

The preliminary benefits analysis is a coarse analysis that was performed for the water contractors to be able to understand with the updated project and what can be expected as to how the project might derive benefits for climate resiliency, seismic resiliency, supply reliability, and operational reliability. Mr. Arakawa noted that it is not intended to be the information that will be used to make a decision on participating in the project and committing to the project; it is provided only for consideration when making the decision on the funding agreements.

The slide shows the analysis that was conducted by the State Water Contractors with input from many different agencies. “On the climate resiliency, if you consider the baseline of the project and you consider the regulations that we have today including the federal ESA, the state ESA, and then you overlay on top of that the existing trend in climate change, including sea level rise, if you actually look at a more aggressive accelerated rate of sea level rise, what kind of benefits could you get from having an intake on the Sacramento River with a tunnel project,” said Mr. Arakawa. “So with this assessment, it’s showing that without the project, you could have a pretty good reduction in supplies, maybe from somewhere around 2.4-2.5 MAF for the State Water Project, that with the project, you could gain back a good amount of that reliability, and so this again is when you consider an accelerated rate of sea level rise. All of these scenarios include a trend of sea level rise, but this one has a more accelerated rate.”

The slide shows the analysis that was conducted by the State Water Contractors with input from many different agencies. “On the climate resiliency, if you consider the baseline of the project and you consider the regulations that we have today including the federal ESA, the state ESA, and then you overlay on top of that the existing trend in climate change, including sea level rise, if you actually look at a more aggressive accelerated rate of sea level rise, what kind of benefits could you get from having an intake on the Sacramento River with a tunnel project,” said Mr. Arakawa. “So with this assessment, it’s showing that without the project, you could have a pretty good reduction in supplies, maybe from somewhere around 2.4-2.5 MAF for the State Water Project, that with the project, you could gain back a good amount of that reliability, and so this again is when you consider an accelerated rate of sea level rise. All of these scenarios include a trend of sea level rise, but this one has a more accelerated rate.”

“If there were to be a seismic event in the Delta similar to what the state analyzed back about 8 to 10 years ago where there’s a plausible major earthquake in and around the Delta that can cause significant damage to the levees; the USGS has projected that type of event,” he continued. “The state concluded that up to 20 islands and levees that are surrounding those islands could fail and cause flooding, and so this seismic resiliency analysis indicates that you could preserve a significant amount of water supply in the State Water Project if there were the intakes on the Sacramento River and not just relying on the south end of the Delta.”

The last part of the analysis looks at water supply reliability and operational resiliency. “We have talked quite a bit over the last several years about Old and Middle River flows or reverse flows in the Delta, but if those were to get more and more stringent both in the fish sensitive periods of December through June, or even go into the remaining part of the year, what kind of impact would that have on the State Water Project,” said Mr. Arakawa. “So if you looked at the without bar, it’s showing that you would have a significant reduction in supply potentially compared to what the project is capable of delivering today at about 2.4 to 2.5 MAF. But with the ability to divert water at the north end of the Delta in addition to the south end, a good amount of that, or pretty much that amount could be protected and that would provide that reliability.”

The last bar on the chart is if there’s increased regulation due to Delta outflow, such as the regulations the State Water Board is proposing with a percent of unimpaired on both the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers in addition to certain flows down that occur in the springtime.

“The combination of those, that all in all, with that water dedication for outflow, there is some capability of getting benefit with the project, but at the same time a lot of the design of those operational restrictions are to keep water in the Delta so that would have a more significant limitation on the ability to protect the water,” Mr. Arakawa said.

AGREEMENT IN PRINCIPLE: STATE WATER PROJECT CONTRACT AMENDMENT

There were a number of public negotiations that considered an opt-in approach, but then the Department made an offer and it became an opt-out approach where every contractor has a contractual responsibility to pay their share of the improvements in the Delta, but there could be a negotiated opportunity to opt-out of the project. The contractors completed negotiations how that could work mechanically and in a contract amendment and that was completed in April of 2020.

“The key thing to know is we’re talking about the contractors having responsibility for this project, but they could potentially opt-out, but they would have to opt-out of the benefits,” said Mr. Arakawa. “The way that would work specifically is that if you are a contractor with a certain amount of Table A contract amount, you would have the ability to opt out of that project for that Table A amount, or alternatively you could stay in and participate in the project, or you could opt-in for additional benefits that those that opt-out may be leaving behind.”

“You have the ability to opt-out of your responsibility in the contract and then there would be other contractors that would take that on, but then you wouldn’t be getting the benefits. If you opt-out of the project, you would not be paying the costs, you would also be agreeing not to gain the benefits. If you do opt-in to the project, you would be paying the additional costs based on whatever proportion you are taking on and then you would be able to get the benefits of the project and the reliability that comes with that through the contract.”

“You have the ability to opt-out of your responsibility in the contract and then there would be other contractors that would take that on, but then you wouldn’t be getting the benefits. If you opt-out of the project, you would not be paying the costs, you would also be agreeing not to gain the benefits. If you do opt-in to the project, you would be paying the additional costs based on whatever proportion you are taking on and then you would be able to get the benefits of the project and the reliability that comes with that through the contract.”

The contract amendment becomes effective once the contract is extended from the year 2035 out 50 years. The allocation would be based on a participation table that has yet to be filled.

Mr. Arakawa then explained how the project would be operated to benefit the participants and not steer benefits to non-participants or to not impact non-participants. “There would be an administrative process that would capture how DWR would manage in San Luis Reservoir, how they would allocate what’s called Article 21 water, unscheduled water, and the more detailed operational measures that are happening on a day to day basis; they would be defined in a white paper that would be similar to how the project operates today. All the project operations are not defined in the contract; there’s a number of administrative processes that are defined that the Department follows, so that’s how the mechanics would work.”

FUNDING AGREEMENTS

Mr. Arakawa then shifted to the funding agreements. As of now, the funding for completing the environmental process, including the EIR and EIS and the endangered species permits, is estimated at $385 million through four years, 2021-2024. The funding agreement would allow for the project to move forward with funds to be spent for both the Department’s oversight and involvement in all of the environmental costs and would include all of the technical work that is necessary to help support the planning process. The funds would be contributed on an agency basis with each participating contractor signing a funding agreement with its associated cost share, depending on their participation level. A contractor can either pay through the statement of charges or through a specified scheduled payment, but it will be based on the funding agreement and not the existing terms of the State Water Project contract.

“The funding agreement would allow for authorizing an agency’s entire share of the planning funds or for the first two years through 2022, and would allow for mechanisms where the boards could authorize the full amount through the end of the planning process or it would allow an agency to come back in two years and get further board direction,” said Mr. Arakawa.

The project will also analyze alternatives that include some capacity for potential participation by the federal water project, but for purposes of paying for the planning costs, these costs would be allocated amongst the SWP contractors.

There are 29 State Water Project contractors. North of Delta contractors don’t use the Delta for conveyance, so they are exempted from having to pay because they won’t receive any benefit from the Delta conveyance. There are 24 south of Delta contractors that would be paying for the planning costs. There may be non-participants that could decide to opt-out of the project.

“The assessment is that there may be another six contractors in addition to the north of Delta that possibly opt out, and so there would be a remaining 18 contractors where those costs would be allocated,” said Mr. Arakawa. “So 65% of the total is just an estimate. It’s not clear yet whether that will be 65%, but when looking at the participation levels and what may come out of agriculture and the considerations that were made in Cal Water Fix and looking at what Metropolitan may need to be prepared for. Again, we estimated up to 65%, approximately the same as what we had in Cal Water Fix, and that is certainly something that the board will be deliberating on.”

UPDATE ON THE DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION AUTHORITY AND THE STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT COMMITTEE

A lot of work has been focused on updating the agreement between the Design and Construction Authority and the Department of Water Resources. There have been some amendments to update how the Department’s process works overseeing the budget, the costs, and the planning funds that are being used now prior to the contributions by the funding agencies. At the September meeting, there was an action to allow the Design and Construction Authority to allow to one ex-officio member and one more regular member on the Stakeholder Engagement Committee.

During the Stakeholder Engagement Committee meetings, the Department is providing updates to the members on the planning process, timelines, what’s being considered and what the alternatives are, as well as refinements to the project that could have some importance to those that live in the Delta, such as construction traffic reductions. The Committee also received a briefing on the Bethany alternative, which is considering connecting to Bethany Reservoir and then to the California Aqueduct that can reduce impacts in the south Delta area.

“The whole idea is getting input from the stakeholders so the project can be defined and refined to minimize and even eliminate impacts where possible,” he said.

The DCA also been providing virtual tours for the stakeholder committee which are available on YouTube.

DISCUSSION HIGHLIGHTS

Director Michael Hogan (San Diego) asked if DWR or Metropolitan will be conducting a new cost benefit analysis. Do you know when we’ll start to see some preliminary analysis on the cost benefit analysis that the board could be briefed on?

“This is to give you an idea of where the starting point is, but as the project gets in the more evaluation and particularly through the alternatives analysis and refinement of the project, I think it’s really key not to presuppose what the project looks like but go through the environmental process and understand what the project will be made up of,” said Mr. Arakawa. “Then during the process, leading up towards finalization, through the draft and the finalization of the EIR, the board would want to be prepared to have an understanding and an indication of where we want to go as we go through that planning process. We would be prepared to provide more detailed information.”

“As we did with Water Fix, we provided information on benefits and cost and we compared that to other options. I suspect we would be doing the same thing. I think in any kind of supply reliability planning process, we would want the board to understand the value of the project, the cost of the project as compared to other things that they would want to consider, so I think that as we get further into the planning process and there’s something to update these costs with and the benefits, we would be doing that with the Board as we did with Water Fix.”

Director Tim Smith (San Diego) asked about the assumption for seismic benefits.

“The USGS has projected what kind of plausible earthquake and the Department has utilized that in the analysis they did about 8 or 10 years ago, looking at what kind of effect could you potentially experience in the Delta and at that time, they identified that the failure of up to 20 islands could occur as a result of a plausible major earthquake in the Delta, so that’s where that information was derived from,” said Mr. Arakawa.

Director Tim Smith (San Diego) asked about the climate scenario.

“Climate change is related to a combination of the changing hydrologic patterns that we would expect the trend to continue at and then also a more accelerated trend for sea level rise,” said Mr. Arakawa. “For sea level rise and for the purposes of looking at the accelerated version, it was about 140 cm, which is something that might have normally been projected at the year 2100 that may be accelerating. But this is a coarse analysis. It gives you a general sense of what the project could do, but I wouldn’t fall in love with any one specific set of assumptions at this point. I think they are based on solid information with the state on the seismic resiliency and on the climate change and sea level projections. But I think as we go forward and particularly as the Board is considering the IRP, I think there’s a lot of room for considering other information as well.”

Director Michael Hogan (San Diego) asked if the preliminary benefit analysis is looking at a possible alternative where we could use local supplies rather than doing Delta conveyance projects.

“This analysis is mainly for the Board to consider whether it has an interest in continuing to fund the planning,” said Mr. Arakawa. “It is not intended to drive what our supply strategy is, and I think the Integrated Resources Plan analysis is going to inform that.”

Director Rusell Lefevre (Torrance) asked if there were plans to move the intakes farther up north on the Sacramento River.

“I think there are two things to consider with sea level rise effects,” he said. “On the one hand, there’s saltwater intrusion and whether these intakes would be able to perform with that projected saltwater intrusion even under the accelerated rate of sea level rise, and there’s the actual design and physical facilities themselves. These intakes, 1 through 5 with Water Fix and now 3 to 5, they’ve been scrutinized very thoroughly and these are the two intakes that have been identified as the most feasible or most acceptable when thinking about fishery concerns and other concerns. The design of the intakes would be done in a way to take into account the actual physical sea level rise or the stage of the water in that area to be able to deal with that. There’s been some modeling done to look at the salt water intrusion and we believe these two intake locations will be able to protect the water quality at the intakes even with the accelerated sea level rise scenario.”

Director Tracy Quinn (Los Angeles) asked if any of the South of Delta SWP contractors indicated that they would definitely be opting in as it sounds like the potential for Metropolitan’s cost share to front the cost might be greater than 65%.

“I want to be sure I don’t mislead anybody,” said Mr. Arakawa. “In the public negotiations, there’s been some indication by some contractors that they plan to opt-out, so there’s been some of that, including some of the smaller agricultural contractors. Kern County has indicated in those discussions that they were planning to be a participant but to what level they would participate is still being worked through in their process. What I envision is that yes, with the north of Delta not participating and with maybe some from the south not participating, there will be some need for other contractors to share in that funding need for the planning. I am anticipating that it’s maybe a bit early to say, but I’m thinking that the 65% is still a good estimate because I anticipate that contractors, many of them will still want to be participating in the planning but they still have to go to their boards and get that decision.”

Director Tim Smith (San Diego) asked what would happen if a very large state water contractor like Metropolitan opted out.

“Any decision that Metropolitan makes has a pretty big impact on the State Water Project, and that’s been the case from the beginning,” said Mr. Arakawa. “We have our State Water Project contract that we have to honor, but in terms of making decisions on discretionary things, we play a huge role, and certainly that will be the case on Delta Conveyance. I think that for continuing the planning process, we’ll need to have a good amount of critical mass of public water agency participants, but if Metropolitan was not participating, I think it would have a big impact and probably would mean that the project would not be going forward.”