The Governor’s Water Resilience Portfolio Initiative underscores the need for communities to maintain and diversify water supplies and to protect and enhance natural environments to prepare for the impacts of climate change. At ACWA’s virtual conference held in July of 2020, a panel comprised of agencies described the experience of the American River region in evaluating climate impacts on their watershed in a new cutting-edge study and the comprehensive suite of projects designed to address increasing threats from more frequent and intense floods, fires, and droughts.

Seated on the panel:

- Tom Gohring, Executive Director of the Water Forum;

- Tony Firenzi, director of Strategic Affairs with the Placer County Water Agency,

- Ellie Alano, Forest supervisor for the Tahoe National Forest, and

- Gary Bardini, Director of Planning for the Sacramento Area Flood Control District.

Located at the confluence of the Sacramento River and the American River, the greater Sacramento area is home to 2 million people. The American River Parkway receives more visitors than Yosemite National Park on an annual basis.

There are numerous state, federal, and local agencies that manage water or engage in the management of water in the region. There are nearly 20 water agencies that serve potable water, the Bureau of Reclamation manages Folsom Reservoir, the US Forest Service has substantial resource management responsibilities in the upper watershed, as well as other smaller agencies, including GSAs, flood control districts, and wastewater agencies. The Water Forum is the agreement and the institution where all of these agencies along with NGOs and other interested stakeholders come together to collaborate on solutions.

There are numerous state, federal, and local agencies that manage water or engage in the management of water in the region. There are nearly 20 water agencies that serve potable water, the Bureau of Reclamation manages Folsom Reservoir, the US Forest Service has substantial resource management responsibilities in the upper watershed, as well as other smaller agencies, including GSAs, flood control districts, and wastewater agencies. The Water Forum is the agreement and the institution where all of these agencies along with NGOs and other interested stakeholders come together to collaborate on solutions.

“Our work within the region has improved the environment, but now we are turning our attention to climate change and how we can preserve water supplies while protecting the environment,” said Jim Peifer, Executive Director of the Regional Water Authority and the Sacramento Groundwater Authority. “We appreciate the Governor’s leadership and the Administration’s work on the Water Resilience Portfolio. We believe a watershed approach to managing water fits nicely within the administration’s draft recommendations, but now the hard work begins for all of us.”

“Our panel members will discuss the initiatives that their agencies are undertaking to prepare for climate change that when taken together, comprise a portfolio of interlocking pieces,” he continued. “We think that our efforts have statewide benefit. Our story is a case study, but we understand that all watersheds are unique. We hope that our experiences that we share today will be useful for other watersheds in adapting to climate change and the increased floods, fires, and droughts that are predicted to come with it. The impacts are scary, but I’m very optimistic that our institutions, relationships, and programs will allow us to adapt.”

The Water Forum Agreement: 20 years of stewardship

Background

Tom Gohring, Executive Director of the Water Forum, began with the background on the Water Forum. In the 1990s, it was recognized that there were critical challenges for water resources in the Sacramento area: there was the need for water to keep the economy growing as well as the water needed for a healthy ecosystem.

“We were growing houses back then, and we had projections that showed that water use was going to continue to go upwards,” Mr. Gohring said. “We also had incredible evidence that showed that our fisheries were in danger, not just steelhead but fall run chinook salmon as well in the Lower American River, and so interested parties came together in the region in the early 1990s and they began a negotiation process.”

The participants included business interests, environmental NGOs, public agencies, and water agencies, and the negotiation was about using water for people or using water for fish.

“This brought together people who view water resources in a very different way,” he said. “Water agencies and some of the other public agencies view water as a resource that is important for human beings and for economic growth. They view their mission as extracting that resource, either from the surface water system or the groundwater system, and making it available to their customers in a way that provides a healthy supply at the lowest possible cost. Other folks who came to the table were environmental advocates and they view water as a natural resource, something that has inherent value remaining in the stream, so those folks came together and looked for a way to meet their common objectives rather than fighting over those two missions.”

“This brought together people who view water resources in a very different way,” he said. “Water agencies and some of the other public agencies view water as a resource that is important for human beings and for economic growth. They view their mission as extracting that resource, either from the surface water system or the groundwater system, and making it available to their customers in a way that provides a healthy supply at the lowest possible cost. Other folks who came to the table were environmental advocates and they view water as a natural resource, something that has inherent value remaining in the stream, so those folks came together and looked for a way to meet their common objectives rather than fighting over those two missions.”

By the year 2000, those folks had created and signed The Water Forum Agreement which was dedicated to the co-equal objectives of a reliable water supply through the year 2030 and protecting the ecological and aesthetic resources of the American River. The agreement included the seven elements listed on the bottom of the slide that they have been slowly and steadily been implementing over the last 20 years.

Meeting the challenges

Mr. Gohring presented a graph showing the projected water demand as it was understood back in 1998. “We were thinking that our surface water demand would approximately double between the year 2000 and the year 2020. In reality, what we saw is that water demand did rise for a while, but now it is actually reduced because of the effects of the drought and the economy, but largely due to the effects of aggressive water conservation on the part of this region, water conservation being one of the elements of the Water Forum Agreement.”

Under the Water Forum Agreement, they’ve seen a turnaround in groundwater conditions. “The graph shows that prior to the Water Forum Agreement, grou ndwater levels in some parts of our region were dropping as much as a foot a year, but because of actions by Water Forum agencies that are described in the Water Forum Agreement, we’ve not only leveled off that overdraft but we’ve recovered it as well.”

ndwater levels in some parts of our region were dropping as much as a foot a year, but because of actions by Water Forum agencies that are described in the Water Forum Agreement, we’ve not only leveled off that overdraft but we’ve recovered it as well.”

They have also made investments of about $24 million on ecosystem restoration on the Lower American River. Mr. Gorhing said that about half of that is from local agency contributions and they were able to leverage a little more than half of that through grants from the state and federal government.

Challenges on the horizon

Mr. Gohring noted there are challenges that remain. They have a flow standard for the American River that they have been working on to move into some durable form. They are hoping that the Folsom Dam temperature control device will be upgraded in the near future. It is expected that the salmon habitat restoration activities basically will continue for the foreseeable future.

“There’s sort of a forever contribution that we need to continue to make in the Lower American River,” he said.

The region is working hard to comply with SGMA, and Mr. Gohring noted that groundwater management is covered in the Water Forum Agreement, but SGMA has raised the bar. They continue to work on drought resiliency as the recent multiyear drought was a bit of an eye-opener for many ratepayers and stakeholders, and it has renewed efforts to create backup water supplies. They are really working to infuse adaptation to climate change into ongoing planning efforts.

The region is working hard to comply with SGMA, and Mr. Gohring noted that groundwater management is covered in the Water Forum Agreement, but SGMA has raised the bar. They continue to work on drought resiliency as the recent multiyear drought was a bit of an eye-opener for many ratepayers and stakeholders, and it has renewed efforts to create backup water supplies. They are really working to infuse adaptation to climate change into ongoing planning efforts.

Mr. Gohring then closed with comments about the Water Forum collaboration. “We continue to have very active participation from local environmental groups, water agencies, and other public agencies. We sometimes don’t agree on every issue, but I have observed them channel each other and speak each other’s point of view in a way to try and meet each other’s objectives, and I think it’s a really gratifying thing for this region. I am hopeful that this kind of collaboration will continue.”

The American River Basin Study

Tony Firenzi, Director of Strategic Affairs for the Placer County Water Agency, then gave a presentation on the findings of the American River Basin Study.

A basin study is a type of study sponsored by the Bureau of Reclamation that evaluates climate change effects for watersheds in the Western US. The basin study looks at the effects of climate change on water supplies and where the gaps are in water supply versus demand. The intended outcome of a basin study is to quantify impacts and then identify strategies and projects for adaptation. These studies utilize global-scale climate models and localized watershed modeling to quantify results.

The Bureau of Reclamation was the federal sponsor of the study; participating local agencies included the Regional Water Authority, Placer County Water Agency, El Dorado County, and the cities of Folsom, Roseville, and Sacramento.

Basin studies are conducted at the watershed level. There was a previous basin study completed for the entire Central Valley, and so this effort builds upon that work in the American River watershed. Specifically, they wanted to expand the Cal SIM modeling to include all the complexities of reservoir operations in the American River watershed.

Basin studies are conducted at the watershed level. There was a previous basin study completed for the entire Central Valley, and so this effort builds upon that work in the American River watershed. Specifically, they wanted to expand the Cal SIM modeling to include all the complexities of reservoir operations in the American River watershed.

The watershed has two groundwater subbasins. Folsom Reservoir is located on the American River and has a capacity of just under 1 MAF. There are three branches of the American River that feed into Folsom Reservoir and upstream storage amounts to about 800,000 acre-feet. Historically, Mr. Firenzi said the watershed experiences about 1 MAF of snowpack and runoff into Folsom Reservoir is nominally about 2.6 MAF.

In the watershed, there are more than 20 water agencies serving just over 2 million people; water use is about 250,000 acre-feet from both surface and groundwater sources. The Lower American River below Folsom Reservoir is home to both fall run chinook salmon and steelhead.

Projected climate impacts

The slide shows the projections for warming by the end of century will be anywhere from 4 to 7 degrees. Three scenarios were analyzed: a warm-wet scenario, a hot-dry scenario, and one in the middle called the central tendency. The graphic shows a slight gradation of temperature warming as the elevation increases. Mr. Firenzi said that the reason for that is the loss of snowpack results in a loss of reflection of radiation, so it gets a bit warmer up in the mountains.

The slide shows the projections for warming by the end of century will be anywhere from 4 to 7 degrees. Three scenarios were analyzed: a warm-wet scenario, a hot-dry scenario, and one in the middle called the central tendency. The graphic shows a slight gradation of temperature warming as the elevation increases. Mr. Firenzi said that the reason for that is the loss of snowpack results in a loss of reflection of radiation, so it gets a bit warmer up in the mountains.

“We’ve already begun experiencing some of this warming, but the additional warming will be experienced either in our lives or perhaps our kids’ lives,” said Mr. Firenzi. “It’s very near.”

The image on the left is the snowpack in February 2018 and on the right is the snowpack in February 2019. The arrow on the right image is pointing to Folsom Reservoir.

The image on the left is the snowpack in February 2018 and on the right is the snowpack in February 2019. The arrow on the right image is pointing to Folsom Reservoir.

“The point of this illustration is to demonstrate our reliance on snowpack for so many things – for water supply, flood control, and the environment,” said Mr. Firenzi. “It’s critical to us. What does the study say about snowpack? Remember I said we had about 1 MAF of snowpack in any given year. We expect to go down to as little as 250,000 MAF up to 500,000 MAF of snowpack. As a percent of precipitation, right now snowpack represents about 20% of total annual precipitation. That percentage is expected to go down to 5%.”

Mr. Firenzi next presented a slide showing runoff into Folsom Reservoir historically and then mid-century and end of century.

Mr. Firenzi next presented a slide showing runoff into Folsom Reservoir historically and then mid-century and end of century.

“On the right, total runoff at any given year, you don’t see a huge effect,” he said. “We don’t expect a real significant decline in total annual runoff; we just simply expect that precipitation to fall as rain instead of snow and occur more in the winter instead of the spring. You can imagine what that does to reservoir operations.”

He pointed out that inflow peaks right now at late spring and early summer, but the peak of inflows will start to occur earlier in the season, so there will be lost storage in the snow that has implications for flood operations, water supply, and the environmental uses.

“So the effects of this lost snowpack are not trivial,” he said. “It would really be a failure of planning and adaptive management to just accept operating at these extremes, like we did in 2015. It was very reactive. We need to be more proactive. If we operate in these extremes without adaptation, the damage to our environment will be very significant as well as the damage to public trust in us as water managers. It’s hard to quantify that but I think as water managers, we’re expected to do something about this.”

Planning for adaptation

So they are planning for adaptation, looking at adaptive strategies and projects that will help fill that gap in water supply versus demand, and not just in the areas that they serve, but holistically throughout the entire watershed. They have a portfolio of ideas and projects that include projects such as forest management, reservoir operations, flow and temperature regimes, and projects that will take reliance off of the Lower American River below Folsom Reservoir which is very sensitive habitat and shift future diversions over to the Sacramento River where there isn’t such an effect on sensitive species.

So they are planning for adaptation, looking at adaptive strategies and projects that will help fill that gap in water supply versus demand, and not just in the areas that they serve, but holistically throughout the entire watershed. They have a portfolio of ideas and projects that include projects such as forest management, reservoir operations, flow and temperature regimes, and projects that will take reliance off of the Lower American River below Folsom Reservoir which is very sensitive habitat and shift future diversions over to the Sacramento River where there isn’t such an effect on sensitive species.

One of the key projects is a water bank, which is a conjunctive use program that takes water supplies when available and stores them. It’s estimated there is about 1.8 MAF of available storage in the region’s groundwater basins which provides ample room for storing water that can be removed when water is needed for consumptive needs and/or for environmental needs. They are now analyzing these projects quantitatively in the basin study but there will be more studies that follow.

Mr. Firenzi then ended his portion by talking about the importance of public outreach. There’s a common narrative with climate change with the public that looks to do good things like solar panels and electric vehicles.

“Those are good things we need to be doing that,” he said. “But unfortunately, minimizing a few degrees of climate change is simply not going to be enough for water and for the environment, and so we need to develop our own narrative as water managers. Our narrative needs to be one of resilience so when we talk to our neighbors and ask them about what climate change means to water and the aquatic environment, we need those people to say, ‘my water agency is investing in resilience.’ I believe we need our public body to understand what resilience means if we are going to gain their favor in investing in climate change resilience, and so that to me is the most critical point of my presentation.”

For more on the American River Basin Study, click here.

Flood management in the American River watershed

Gary Bardini, Director of Planning for the Sacramento Area Flood Control Agency (SAFCA), then discussed the flood management aspects of the watershed. The Sacramento Area Flood Control Agency has been implementing projects for the last 30 years and will continue to do so now and into the future, he said.

Over the last 20 years, the Sacramento Flood Control Agency, the Army Corps of Engineers, and the state of California has invested about $2 billion for flood management in the region. A number of these projects include improvements to the levee systems in the areas along the Sacramento River and the American River. More notably is the recently completed spillway project at Folsom Lake, a joint federal project that cost $1 billion; completing the project makes using Forecast Informed Operations possible to manage the flood control operations of the reservoir based on five-day advance forecasts, which is one of the elements that will really improve regional flood management in the region, he said.

Current projects

Currently, SAFCA has nine major projects occurring under a number of authorizations with the Corps of Engineers, including improvements to levees in the Natomas area and improvements at Folsom Dam including raising the dam by 2 and a half feet, improving the existing spillways, and improving temperature management. SAFCA is also working on the American River to improve the ability to pass high flows, as well as along the Sacramento. They are also working to widen the Sacramento Weir and bypass into the Yolo Bypass.

Currently, SAFCA has nine major projects occurring under a number of authorizations with the Corps of Engineers, including improvements to levees in the Natomas area and improvements at Folsom Dam including raising the dam by 2 and a half feet, improving the existing spillways, and improving temperature management. SAFCA is also working on the American River to improve the ability to pass high flows, as well as along the Sacramento. They are also working to widen the Sacramento Weir and bypass into the Yolo Bypass.

“The sum total of these projects over the next decade which are currently in implementation will be over $2 billion,” said Mr. Bardini. “So the Sacramento Flood Control Agency over the next ten years and looking over the last 40 years is going to be looking at investing about $4 billion into the region to deal with the flood risk of a river city.”

He then presented a chart showing Sacramento’s flood protection as compared to other river cities, noting that the city still sits just under 100-year flood protection in a number of areas and the projects underway are looking to boost the city to a 300 year level of protection.

He then presented a chart showing Sacramento’s flood protection as compared to other river cities, noting that the city still sits just under 100-year flood protection in a number of areas and the projects underway are looking to boost the city to a 300 year level of protection.

“With the climate uncertainty, we at the city, the county, and the region are trying to achieve similar higher level protection to deal with climate uncertainty and the risky consequence of flooding a major metropolitan area,” he said. “So SAFCA is not only looking at making improvements today, but continue to make improvements to achieve at least about a 500 year level of protection.”

Building a resilient flood management system

One of the fundamentals of a flood control project and more importantly, integrated water management, is resiliency, he said. “The state of California has picked up on the resiliency necessity to basically address not only the public safety and public interest, but also the environment and the resiliency of our economy.”

There are four measurable qualities of resiliency: making systems robust and redundant, having the ability to be resourceful in operations, and the ability to recover from a natural disaster, he said. These are really significant and have to be managed together as a system to provide resiliency, so with that, SAFCA has been looking at increasing resiliency by being robust and redundant.

There are four measurable qualities of resiliency: making systems robust and redundant, having the ability to be resourceful in operations, and the ability to recover from a natural disaster, he said. These are really significant and have to be managed together as a system to provide resiliency, so with that, SAFCA has been looking at increasing resiliency by being robust and redundant.

In the American River watershed, average runoff is just under 3 MAF per year, but the three-day volume is the most significant risk to the community of Sacramento, which in wet years, is estimated to be just under 2 MAF, so that means 70% of the annual runoff coming in just three days.

”There’s the need for not only making the system better along the main stem and Folsom reservoir system but SAFCA is looking for improving the management in the upper reservoirs, better forecast operation, furthering from five day to seven day forecasting, and then having more redundancy downstream in the bypass system away from the major urban metropolitan areas,” Mr. Bardini said.

He presented a slide showing the plan for reaching 500-year flood protection in the American River. SAFCA is currently working with the Army Corps of Engineers to increase storage at Folsom Lake and improve the channel capacity in the American River. Those improvements would allow a release of at least 1 MAF in a three day period through the channel at 160,000 cfs and increase storage up to about 500,000 AF. They would also like to build additional more storage upstream as well.

He presented a slide showing the plan for reaching 500-year flood protection in the American River. SAFCA is currently working with the Army Corps of Engineers to increase storage at Folsom Lake and improve the channel capacity in the American River. Those improvements would allow a release of at least 1 MAF in a three day period through the channel at 160,000 cfs and increase storage up to about 500,000 AF. They would also like to build additional more storage upstream as well.

“What we saw is that the past is not indicative of the future and we recognize that the opportunity to have high intensity storms, 500 year events may be more often and change in duration, and we have to be prepared to address this,” said Mr. Bardini.

From a watershed perspective, SAFCA is promoting and working in cooperation with a number of agencies for a number of upstream improvements at Hell Hole, Union Valley, and French Meadows, working with forest practices in the upper watershed and looking at how to improve reservoir operations and inflow forecasting. They have a number of efforts underway with modifications at Folsom Dam.

From a watershed perspective, SAFCA is promoting and working in cooperation with a number of agencies for a number of upstream improvements at Hell Hole, Union Valley, and French Meadows, working with forest practices in the upper watershed and looking at how to improve reservoir operations and inflow forecasting. They have a number of efforts underway with modifications at Folsom Dam.

“We’d love to see that we could integrate these with much better system management where we can promote better active water resource management, not only just for the environment, but also looking at how we can improve groundwater management in the region, and connecting all of these into what we call a broader Flood MAR type of concept would help the resiliency of the watershed,” he said.

The Department of Water Resources has laid out the fundamental framework for developing a multi-benefit project, so Mr. Bardini took thirteen of the items and put them into three major groups.

The Department of Water Resources has laid out the fundamental framework for developing a multi-benefit project, so Mr. Bardini took thirteen of the items and put them into three major groups.

“There are many of those that are needed in the flood institutional management and a number of those that are necessary in the water institutional management; then you have to bring them all together in a broader regional watershed perspective with institutional agreements and management to finally provide for a truly integrated watershed. These efforts have to be navigated to promote the higher levels of system protection that is needed. Without these types of arrangements, you can’t achieve some of the objectives we just outlined for flood control in the region.”

With that concept in mind, SAFCA working with the Bureau of Reclamation took the initiative to look at the potential water reliability and flood control benefits would be if they were to link upstream watershed reservoirs, Folsom operations with the raise, and groundwater banking in the south American River Basin. They looked at the additional flexibility in raising Folsom Dam, going to 7-day or 10-day forecasts, pre-release strategies in the operations of Folsom South Canal, and looking at opportunities in rural areas for groundwater recharge, both active or in-lieu.

The slide shows the opportunities to do recharge in the south basin. “We feel that there are opportunities to provide at least an additional 250,000 AF of potential water supply benefit and reliability in the region for any number of purposes just by linking these efforts,” said Mr. Bardini.

The slide shows the opportunities to do recharge in the south basin. “We feel that there are opportunities to provide at least an additional 250,000 AF of potential water supply benefit and reliability in the region for any number of purposes just by linking these efforts,” said Mr. Bardini.

“So in summary, better regional cooperation is a requirement under a broader watershed strategy that looks at everything from a broader system and within that system, the ultimate aspect of the objective among all the parties is working together is to provide not only for the public safety and flood protection that the region is looking for, but also to promote the environment in the region and the resource management and look at the water reliability and other facets that promote for a stable economics of the region,” he said.

“All these things with agencies working together is what’s necessary to bring it from the levels that we’re at and the resiliency we currently have in the region to get to a much higher resiliency. The state administration is promoting it as well. We’re looking to partner with the state and federal agencies to continue to work to a much higher level resiliency for the Sacramento region.”

Forest restoration and resiliency

Eli Ilano is the Forest Supervisor for the Tahoe National Forest. He began by noting that the mission of the US Forest Service is to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations.

There are 156 national forests across the country, 18 of which are in California. Nationally, that’s about 193 million acres that are managed for a variety of purposes. The Tahoe National Forest encompasses 1.2 million acres surrounding Lake Tahoe and nestled in between Sacramento and Reno.

Highway 80 runs right through the middle of the Tahoe National Forest, and there are communities on both sides.

Highway 80 runs right through the middle of the Tahoe National Forest, and there are communities on both sides.

“We have a lot going on both in serving the Sacramento and San Francisco areas of California, but also the Reno area, so water from the Tahoe National Forest serves both of those places,” said Mr. Ilano. “There’s about 2.5 MAF of water that flows from the Tahoe for residential and industrial use in those communities.”

Under a natural regime, forests like the Tahoe in the Sierra Nevada are called fire-adapted ecosystems in which frequent fires would naturally have occurred. Most of those fires would have been small to moderate-sized, primarily burning the understories of the forests and creating a lot of openings in the forest. As communities and human settlements moved into forested areas, along came infrastructure, housing, businesses, roads, and waterways, and the country wanted all of those natural fires suppressed to protect that human development.

“So we are sort of about 150 years of pretty serious fire suppression, and what that has resulted in some forests being at risk based on a number of factors,” he said. “When that frequent low to moderate fire did not occur, we have ended up with greater ground material as in the upper left photo. Also we start to encounter competition for the water resources, sun resources, and the nutrients in the soil, and that can lead to mortality when you have too many trees competing for those resources, so in the upper right picture you see some tree mortality that occurred due to the drought a few years ago. In the lower left corner you see a picture of overly dense forest at the ground level, and you can see that it’s so thick that if a fire were to enter there, all those trees would be at risk.”

“So we are sort of about 150 years of pretty serious fire suppression, and what that has resulted in some forests being at risk based on a number of factors,” he said. “When that frequent low to moderate fire did not occur, we have ended up with greater ground material as in the upper left photo. Also we start to encounter competition for the water resources, sun resources, and the nutrients in the soil, and that can lead to mortality when you have too many trees competing for those resources, so in the upper right picture you see some tree mortality that occurred due to the drought a few years ago. In the lower left corner you see a picture of overly dense forest at the ground level, and you can see that it’s so thick that if a fire were to enter there, all those trees would be at risk.”

Climate change is projected to impact the forest in many ways, said Mr. Ilano. There are temperature increases expected which we are already experiencing. Precipitation is likely to change; the level of precipitation is a little bit uncertain but there will likely be more extremely wet and more extremely dry years. Snowpack is expected to decline; all the models are showing at least a 20% decline, and even up to 90% in some portions of the state.

And larger, more severe wildfires. The map shows the moderate to high wildfire potential across the state; the darker the red, the higher potential for wildfire. Across the Sierra Nevada, we’re seeing much higher potential for severe wildfire, he said.

And larger, more severe wildfires. The map shows the moderate to high wildfire potential across the state; the darker the red, the higher potential for wildfire. Across the Sierra Nevada, we’re seeing much higher potential for severe wildfire, he said.

Mr. Ilano then showed some pictures from the American Fire which occurred in the Middle Fork of the American River watershed in 2014. The fire burned very hot and there was a very, very high mortality rate in various parts of the fire area. He said that it’s very hard to recover to a more natural functioning ecosystem after an event like this; the soils are rendered unproductive, there are large amounts of standing dead trees, and the erosion potential is great.

There were similar impacts after the Kings Fire, which was in the South Fork of the American River watershed, costing the Placer County Water Agency millions of dollars to remove sediment from the drainage facilities as a result of that fire.

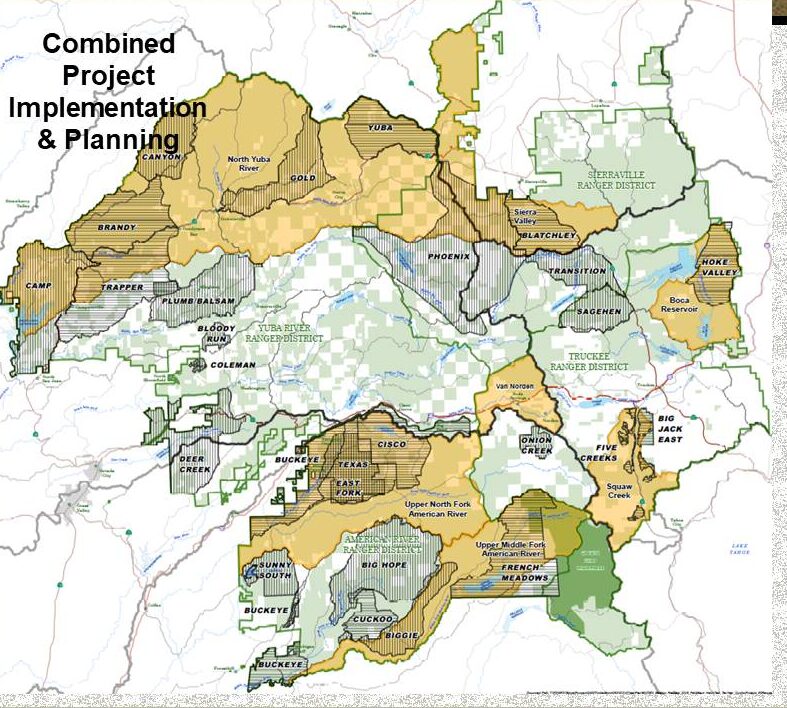

To address this on the Tahoe National Forest, they have identified high priority watersheds shown in yellow on the map where they are focusing resources, time, and energy which include the North Fork and portions of the Middle Fork of the American River.

The areas that are hash tagged on the map below are areas where they are either actively working on projects or planning projects, such as the French Meadows project which is where they are working with the Placer County Water Agency, Placer County, the Nature Conservancy, and other partners to complete a 26,000-acre forest health and restoration project.

Types of forest treatments

Mechanical thinning: Using large pieces of machinery, trees and ground materials are removed. The pictures are a before and after of the French Meadows Reservoir; it’s thinning out some of the trees so it’s not quite as dense, Mr. Ilano said. “Those remaining trees are going to be healthier and they are going to have a greater chance of survival. Also were a fire to go through here, we’d have a much greater chance of containing it and controlling that fire.”

Mechanical thinning: Using large pieces of machinery, trees and ground materials are removed. The pictures are a before and after of the French Meadows Reservoir; it’s thinning out some of the trees so it’s not quite as dense, Mr. Ilano said. “Those remaining trees are going to be healthier and they are going to have a greater chance of survival. Also were a fire to go through here, we’d have a much greater chance of containing it and controlling that fire.”

Hand thinning: Crews use hand tools and chain saws, remove selected trees, ground fuels, and brush, either piling them or removing them as they go along.

Hand thinning: Crews use hand tools and chain saws, remove selected trees, ground fuels, and brush, either piling them or removing them as they go along.

Prescribed fire: The use of prescribed fire is another important tool. The picture shows a prescribed fire underway; Mr. Ilano pointed out that the fire is on the ground and not in the canopy of the trees; it’s creating a lot of smoke, but that smoke is very temporary. “This is a long term important strategy to maintain these forests and to reintroduce that natural maintenance tool of fire but in a controlled way in order to keep the fire danger low and to keep the natural ecosystem functioning properly.”

Prescribed fire: The use of prescribed fire is another important tool. The picture shows a prescribed fire underway; Mr. Ilano pointed out that the fire is on the ground and not in the canopy of the trees; it’s creating a lot of smoke, but that smoke is very temporary. “This is a long term important strategy to maintain these forests and to reintroduce that natural maintenance tool of fire but in a controlled way in order to keep the fire danger low and to keep the natural ecosystem functioning properly.”

Land acquisition: Land acquisition is another tool that is used to protect these watersheds. “A couple of years ago, working with a number of partners, we acquired the very headwaters, the very top of 3300 acres of the Middle Fork of the American River watershed. It was added to the Granite Chief Wilderness, so the very headwaters of the Middle Fork of the American River are protected from development and other things that might adversely impact the water quality in the forest.”

Land acquisition: Land acquisition is another tool that is used to protect these watersheds. “A couple of years ago, working with a number of partners, we acquired the very headwaters, the very top of 3300 acres of the Middle Fork of the American River watershed. It was added to the Granite Chief Wilderness, so the very headwaters of the Middle Fork of the American River are protected from development and other things that might adversely impact the water quality in the forest.”

Implementation costs

Mr. Ilano presented a slide showing the costs of the Yuba Project in the Yuba River watershed. “In this particular project, the implementation costs were about $5 million, but the actual value of the timber coming off of the land was about $1 million, so we all had to find $4 million of other funding to implement that project,” said Mr. Ilano. “For this particular project, it was a combination of state grants, the Yuba Water Agency contributed, the federal government contributed, some nonprofits contributed, and that’s how we have to work in order to complete these projects because of their expense.”

Mr. Ilano presented a slide showing the costs of the Yuba Project in the Yuba River watershed. “In this particular project, the implementation costs were about $5 million, but the actual value of the timber coming off of the land was about $1 million, so we all had to find $4 million of other funding to implement that project,” said Mr. Ilano. “For this particular project, it was a combination of state grants, the Yuba Water Agency contributed, the federal government contributed, some nonprofits contributed, and that’s how we have to work in order to complete these projects because of their expense.”

Q&A

Question: You had mentioned that we need resilience to resonate with our public in order to achieve the necessary investments. Do you have any recommendations for natural resource managers to achieve this goal? What can we be doing?

“I think to answer that, I want to give a few brief examples of public engagement and then talk about what that means moving forward,” said Tony Firenzi. “The Regional Water Authority conducted a 2016 public focus group where they engaged business and local government influencers in topics of water management. They asked them questions, just trying to determine if they are giving the right narrative, do people understand what they were saying? It was kind of a poll but a little bit deeper dive than a typical poll. I was inspired to find out in that event that those kind of people, they understood what conjunctive use is – even the word water bank was understood by some, and what they also understood was that these were tools for dealing with stressed water systems in the future. That is a polling of what I would call engaged, informed people but they weren’t water managers. It was inspiring to know that they knew what we were talking about here.”

“More recently, in reaching out to more of the norms of society, polling this spring, even in light of a pandemic has shown that people are really interested in investing in climate resiliency. Polling for the proposed climate resiliency bond had very favorable results over 60% so I think people get it. They understand the problem.”

“But what we need is for people to also understand the solution. I’m not quite sure that our public body is there yet, and I think in order for them to understand the solution, you have to make them part of the solution,” continued Mr. Firenzi. “There are people investing personally in solar panels and electric vehicles and that kind of thing. Well unfortunately, we all can’t have our own local water bank or conjunctive use program on our residential lot, so we need to find a means of people feeling they are investing in these solutions personally by investing through us as water management industry. To answer the question, it’s a bottom up approach. We need to work with our public body and engage them.”

Question: Is it important to engage NGOs, and how do you do that?

“A resounding yes,” said Tom Gohring. “It was important 20 years ago when many of us were cutting our teeth in water management and I think it’s even more important now. Our public, our new generation expects to be part of decisions, governmental decisions, resource decisions, and not engaging them means we almost force them to become our opposition. I think part of the experience we’ve had in this region is that we take the other path by inviting NGOs and other members of the public into the process on the front end, they can become champions of the process, rather than opposition.”

“As an example of working with the community and working with stakeholders, Sacramento Area Flood Control Agency in doing bank protection work on the American River have worked with the Water Forum,” said Gary Bardini. “The Lower American River Task Force is an example of carrying out a body of work and evaluation in a very public transparent way, inviting the NGOs all the way from the beginning all the way to the point where we develop projects and go out to a broader public engagement. So we think it’s very important, in fact it’s critical when engaging in anything in the waterway to have active participation with the NGO community.”

“From the federal perspective, we simply these days cannot accomplish what we want to accomplish without having NGOs and even just citizens involved,” said Eli Ilano. “Everything from ideas and knowledge that these folks bring to project planning, to the resources they bring for project implementation, the people power, the big volunteer days, grant writing, all kinds of things that we simply cannot get it done without the NGO community.”

Question: If you could receive a grant that’s unlimited for one thing, what would it be?

“The water bank,” said Tony Firenzi. “I mentioned that in my presentation, it’s something that our region is highly invested, and we’re highly invested in it because we think it has great merit and great value. Let me expand on that more broadly. Where I think such lofty goals should be invested, if we had those kinds of resources, anything that produces adaptive management, anything that produces flexibility in our operations, interconnecting water systems and allowing water to be distributed in time so it can go to the best use. Anything along those lines is my broader answer, and for us, that’s the regional water bank.”

“This is the crazy idea,” said Tom Gohring. “I would invest in a solar generating system that covers 2/3rds of the area of Lake Natoma, that would serve two purposes. It would reduce the temperature gain of Lake Natoma which would have a demonstrable fishery benefit in the Lower American River. It would also create power generation … “

“A bioenergy wood processing facility in the upper watershed to process all of the material we need to use, also generating power and clean burning, no emissions,” said Eli Ilano.

“I’d like to see where eventually, federal, local, and state agencies actually work together as institutions managing the resiliency and actually getting out of the accounting of what it does,” said Gary Bardini. “If you have basic cooperation among all in terms of what’s needed, that’s just the investment that’s needed in the watershed versus doing a new accounting exercise of what the benefit of individual actions are.”

Concluding remarks

Moderator Jim Piefer then wrapped it up with some concluding remarks. “You heard from four panel members today talking about projects they are doing to adapt to climate change, and all these projects work together better. These projects are helpful to one another: the improvements in the forest help with water supply and they help with flood control. The project that Gary was talking about is helpful for water supply and flood control at the same time. The projects that Tom talked about and the initiatives that we have under the Water Forum help with all these things and help with the environment.”

“These are important multi-benefit projects, and we are hopeful to see the resiliency portfolio in its final form coming soon and we hope to be able to have the support from the federal and state governments in our work within the watershed, and the work they’ve like to see done. We hope to become partners with them and move forward in adapting to climate change.”