With water availability being an important concern, water managers often use water budgets to quantify and manage water resources. A water budget is an accounting of the rates of the inflows, outflows, and changes in water storage in a specific area; however, as simple as that might sound, developing an accurate water budget can be a difficult and challenging endeavor.

To address this problem, the Department of Water Resources has developed a water budget handbook, which is intended to demystify the process of developing a water budget by distilling the process down into specific steps, providing guidance as well as specific advice on how to determine a water budget, with or without the use of models. In the spring of 2020, Department staff held a webinar to introduce water managers and interested stakeholders to the content in the water budget handbook.

The water budget is important because it provides an understanding of historical conditions and how future changes to supply, demand, hydrology, population, land use, and climate may affect the water resources of the area. Water budgets are an important tool for water agencies for things such as water supply planning and evaluating the effectiveness of management actions to ensure long-term sustainability of surface water and groundwater resources in the area.

The water budget is important because it provides an understanding of historical conditions and how future changes to supply, demand, hydrology, population, land use, and climate may affect the water resources of the area. Water budgets are an important tool for water agencies for things such as water supply planning and evaluating the effectiveness of management actions to ensure long-term sustainability of surface water and groundwater resources in the area.

Recent legislation, including the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act and Assembly Bill 1668, has codified water budget development to be part of groundwater sustainability plans and agricultural water management plans. Recently released governor’s draft water resilience portfolio has actions recommending the development of water budgets as an integral component of planning to advance water resilience in California.

The Department of Water Resources developed the draft Handbook for Water Budget Development as a practical reference guide for the California water resources community for determining water budgets for any geographic area and time period using either a modelling or a non-modelling approachs. Development of the handbook was informed through two water budget pilot projects in Tulare Lake and Central Coast hydrologic regions which identified challenges in water budget development such as inconsistent definition of water budget components, non-standard accounting techniques, and inadequate documentation. Development of the handbook was an effort between staff from multiple DWR programs, the USGS, the State Water Board, academia, and others

The Department of Water Resources developed the draft Handbook for Water Budget Development as a practical reference guide for the California water resources community for determining water budgets for any geographic area and time period using either a modelling or a non-modelling approachs. Development of the handbook was informed through two water budget pilot projects in Tulare Lake and Central Coast hydrologic regions which identified challenges in water budget development such as inconsistent definition of water budget components, non-standard accounting techniques, and inadequate documentation. Development of the handbook was an effort between staff from multiple DWR programs, the USGS, the State Water Board, academia, and others

The handbook fills a significant gap by systematically presenting relevant information in a single publication, including foundational concepts of total water budgets, a water budget accounting template, efficient ways for selecting an approach, and guidance on documenting water budgets.

“We believe use of the handbook will facilitate consistent development and communication of water budget information by diverse water management entities,” said Abdul Kahn with DWR’s Division of Planning. “We also believe that the handbook will reduce the cost of water budget development and documentation for local and regional agencies.”

FOUNDATIONAL CONCEPTS OF A WATER BUDGET

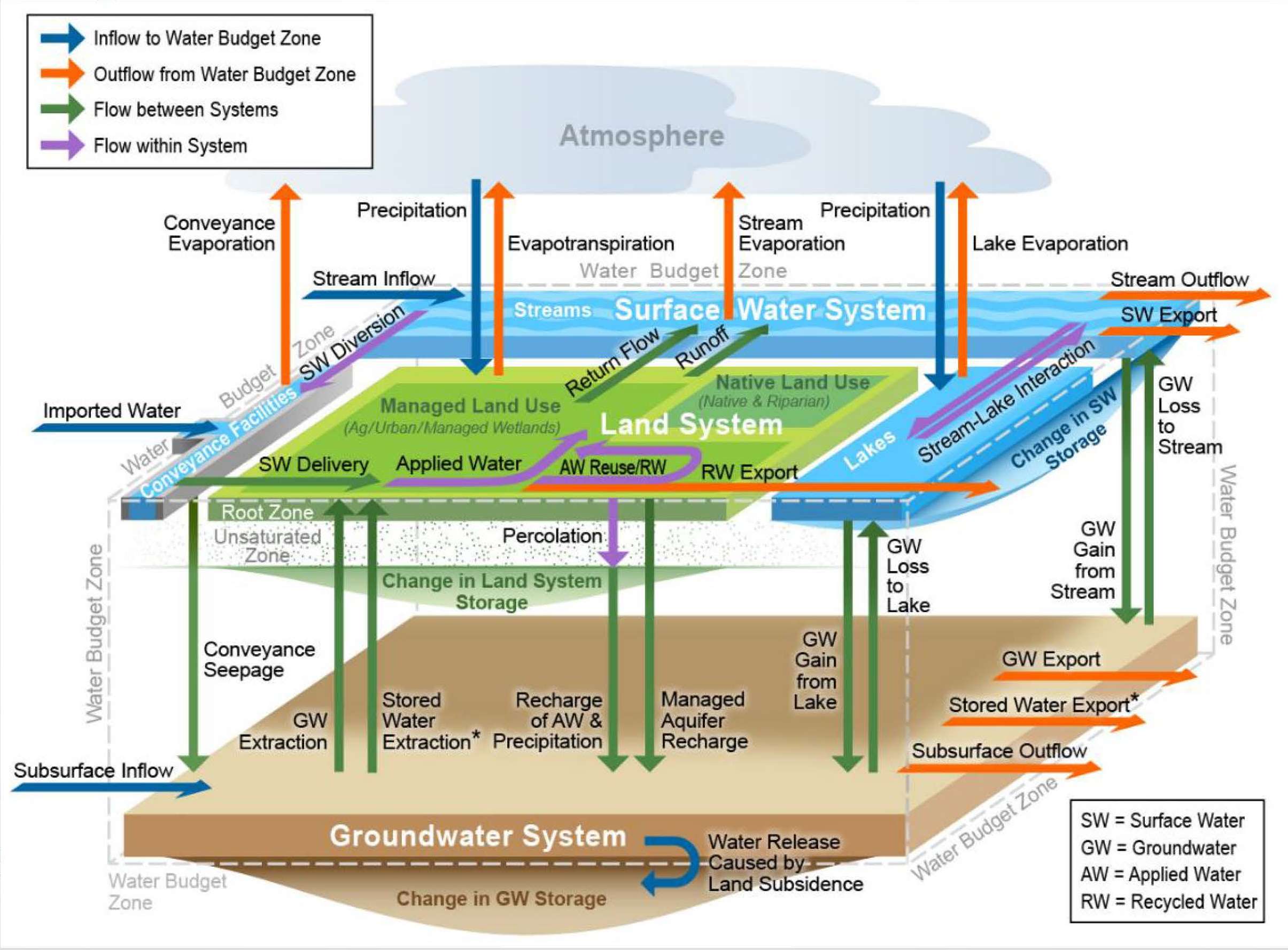

Abdul Kahn presented a three-dimensional representation of water budget components. The total water budget is a comprehensive accounting of all inflows and outflows from three interacting systems in water budget zone: the land system, the surface water system, and the groundwater system. A water budget can be prepared for any user-defined water management area such as a watershed, a groundwater basin, or a water district.

Abdul Kahn presented a three-dimensional representation of water budget components. The total water budget is a comprehensive accounting of all inflows and outflows from three interacting systems in water budget zone: the land system, the surface water system, and the groundwater system. A water budget can be prepared for any user-defined water management area such as a watershed, a groundwater basin, or a water district.

On the diagram, flows entering the water budget zone are shown as blue arrows, flows leaving the water budget zone are shown as orange arrows, flows from one system to another are shown as green arrows, and internal flows within a system are shown as purple arrows.

“Depending upon the particular need of an agency, and importance of individual water budget components for an area, a few, some, or all components shown on this diagram will need to be accounted for in a water budget,” said Mr. Kahn. “For example, an area which does not have any groundwater component, the water budget for that area would focus only on the land and surface water systems, so only the blue system shown on the diagram and the green system shown on the diagram would need to be considered.”

STANDARDIZING VOCABULARY AND WATER BUDGET ACCOUNTING STANDARDS

The draft Handbook for Water Budget Development includes definitions for each component of the water budget. This common vocabulary was developed with multiple DWR programs, the State Water Board, the USGS, and academia to facilitate consistent understanding and communication of water budgets, Mr. Kahn said. Standardized water budget accounting templates are also included in the handbook to help organize and present inflows and outflows for the land system, the surface water system, and the groundwater system, as well as the total water budget.

“The total water budget in this context is the aggregation of water budgets of the three interacting systems,” said Mr. Kahn. “This accounting template, we believe, will facilitate standardization, error checking, and correction of water budget development and estimates. Use of a standardized template, we believe will also result in improved communications and coordination with neighboring water agencies through consistent water budget accounting across boundaries and water budget zones.”

TO MODEL OR NOT MODEL?

The water budget handbook is intended to assist water managers having different levels of data, capacities, and resources, so the handbook provides two approaches to water budget development: An approach that uses models and an approach that does not.

The modeling approach refers to using an integrated numerical model that includes simulation of processes in the land system, surface water system, and groundwater system at various time scales such as daily, monthly, or annually. The modeling approach is the most comprehensive way to develop a total water budget for the water budget zone. The development of a defensible, integrated numerical model that is well calibrated and has stakeholder buy-in requires considerable investment in data, tools, people, and process.

On the other hand, the non-modeling approach is used in the absence of a robust accepted integrated numerical model or when a model may not be needed for estimating the water budget components. The non-modeling approach is an accounting method that uses a combination of assumptions, process equations, and available basic meteorological, hydrologic, and other related data to develop spatially and temporally lumped estimates of various water budget components.

basic meteorological, hydrologic, and other related data to develop spatially and temporally lumped estimates of various water budget components.

The slide shows the logical steps in determining when to use a non-modeling approach and when to use a modeling approach. There may be cases when a hybrid approach of both modeling and non-modeling may be best suited for an area, depending on data availability, and existing model features.

“Appropriate and sufficient documentation of the water budget is essential for stakeholders, neighboring jurisdictions, and regulators to understand the basis of the developed water budget,” said Mr. Kahn. “Recommendations can also serve as a knowledge base for a water agency, as well as facilitating staff development and succession planning. Documentation of water budgets is important for both modeling and non-modeling approaches.”

SECTIONS 3, 4, AND 5: LAND, SURFACE WATER, AND GROUNDWATER SYSTEMS

Next, Todd Hillaire with DWR’s Northern Region Office dove into the handbook sections to show how the handbook provides guidance for calculating water budget components.

Sections 3, 4, and 5 cover the land system, the surface water system, and the groundwater system respectively; these sections are key to the approach to developing the total water budget. The handbook breaks down the process into smaller pieces. It considers each of the systems and all the interacting components.

Sections 3, 4, and 5 cover the land system, the surface water system, and the groundwater system respectively; these sections are key to the approach to developing the total water budget. The handbook breaks down the process into smaller pieces. It considers each of the systems and all the interacting components.

The handbook is designed so that a user can go through each section in sequence and put together a water budget, or if the user is experienced and just wants to know how to compute one component, they can easily find the section and the different methods of calculating it.

“Where we can, we have subsections that have several water budget components combined together, and where multiple water budget components might use similar techniques, we’ve put them together to create some utility and help focus on efficiently going through this,” said Mr. Hillaire.

Section 3: Land systems

In each of the sections, the schematic from the total water budget is extracted to help the user focus on the related components; in the graphic shown on the slide, it is the land system. He pointed out that the budget accounts for changes in the root zone storage, the unsaturated zone storage, and the land system storage. Within the land system, both native land uses and managed land uses are identified.

In each of the sections, the schematic from the total water budget is extracted to help the user focus on the related components; in the graphic shown on the slide, it is the land system. He pointed out that the budget accounts for changes in the root zone storage, the unsaturated zone storage, and the land system storage. Within the land system, both native land uses and managed land uses are identified.

“The idea here with the total water budget, we are doing mass balance and we’re going to account for everything so both native and managed land uses are presented here,” said Mr. Hillaire.

“When we do a water budget for managed land uses, we want to dive into the details because a water budget is supposed to tell something how water management is occurring in any one area, in this case, a water budget zone,” he continued. “So it can provide more utility, we’ve broken things down by agricultural land, managed wetlands, and urban areas.”

The objective of the water budget is to incorporate all of the things that affect water management. Water applied to agricultural lands is applied water; the diagram shows the component and interactions of the disposition of that supply. Managed wetlands is similar to ag except it has generally ponded water in its management.

The objective of the water budget is to incorporate all of the things that affect water management. Water applied to agricultural lands is applied water; the diagram shows the component and interactions of the disposition of that supply. Managed wetlands is similar to ag except it has generally ponded water in its management.

The urban area diagram shows a comprehensive accounting of flows: landscape, indoor water use, wastewater going to collection facilities, or stormwater collection that can be picked up and used, and the disposition of those flows into recycled water or managed aquifer recharge.

“For characterizing a complete water budget, you don’t actually have to use every single term, but it’s there for your use and for your ability to communicate with your stakeholders using pertinent information,” said Mr. Hillaire.

To help understand applied water supply and the disposition of that supply, the handbook includes some bar charts. For example, the bar chart for urban lands on the right side of the screen shows precipitation and applied water as supplies: surface water, groundwater, stormwater, extraction, reuse, and recycled water all help to make up the applied water component supply. The chart also shows the disposition of that supply: evapotranspiration, recharge of applied water, return flow of applied water, and etc.

To help understand applied water supply and the disposition of that supply, the handbook includes some bar charts. For example, the bar chart for urban lands on the right side of the screen shows precipitation and applied water as supplies: surface water, groundwater, stormwater, extraction, reuse, and recycled water all help to make up the applied water component supply. The chart also shows the disposition of that supply: evapotranspiration, recharge of applied water, return flow of applied water, and etc.

“The idea is with the handbook is to help characterize and provide an understanding of these water budget components and where all this water goes to and the need to calculate all these particular components,” said Mr. Hillaire.

He then gave an overview of the type of information that’s in each subsection of the water budget components. Each of the subsections in the handbook is laid out in a similar way.

Subsection 3.4 of the land system is evapotranspiration. In each subsection, there is the definition and an explanation of what evapotranspiration is and how it is determined. Next, methods of determining ET are presented; there are four: obtain estimates from available reports, obtain estimates from models, use a crop co-efficient approach, or use a water duty based approach to calculate ET.

Another example of the kind of information included in the handbook is method 3 for estimating applied agricultural water volume. The arrows on the slide show the information on using the crop-based ET approach, including a discussion of the approach and the equations that are used to calculate it.

“The bottom highlighted equation is applied water is equal to acreage multiplied by unit ETAW which is on-farm ET per acre; you divide that by irrigation efficiency, so it’s important to know that,” said Mr. Hillaire. “We have to know something about cultural practices so we add that, and if we do that by individual crop and sum it up, you’d get a pretty good handle on your applied water within your water budget zone, so we lead the user through that.”

The slides below show how the handbook provides step by step instructions, detailing how the calculations are made and includes reference tables. The steps build upon each other to help the user get through the calculation to estimate applied water volume.

The handbook provides abundant examples of component calculations, and includes tables of information; this is important as many components are not isolated but can build off of each other, he said.

“You can use applied water if you know something about land use and mapping, and water sources by acreage, so you could actually end up calculating groundwater extraction, applied water reuse, and surface water supply from those estimates,” Mr. Hillaire said. “You can at least get initial estimate to start your water budget. We provide an example calculation table of what we did to make some estimates of surface and groundwater extractions from some very basic data … We’re helping to provide a lot of information to help make estimates of these components with different techniques or methods.”

He then walked through a short example that is in the handbook for 1000 acres of corn. “You can see the diagram down at the right hand corner, we’ve taken a water budget schematic for agriculture and highlighted the applied water component, and the return flow, applied water reuse and the recharge of applied water, and we’re going to make estimates of those,” he said. “If we have some basic characteristics or information that we know, such as the ET of applied water, in this case it’s 2.2 acre-feet as an example. We can use the table as a guide knowing something about the irrigation methods. In this case, it’s furrows and siphon tubes, and we can work that up on that table to pull out what are reasonable estimates of recharge and return flow using those types of estimates to start to get into the right ballpark of where do we think all the water is going.”

He then walked through a short example that is in the handbook for 1000 acres of corn. “You can see the diagram down at the right hand corner, we’ve taken a water budget schematic for agriculture and highlighted the applied water component, and the return flow, applied water reuse and the recharge of applied water, and we’re going to make estimates of those,” he said. “If we have some basic characteristics or information that we know, such as the ET of applied water, in this case it’s 2.2 acre-feet as an example. We can use the table as a guide knowing something about the irrigation methods. In this case, it’s furrows and siphon tubes, and we can work that up on that table to pull out what are reasonable estimates of recharge and return flow using those types of estimates to start to get into the right ballpark of where do we think all the water is going.”

“There are tables that provide information on types of irrigation systems, the water efficiency of how water is distributed; there is water going to air evaporation, soil evaporation, and canopy evaporation, but what’s important, what is recharge and surface runoff, and then looking at overall efficiency. These are some tools provided here to help make these calculations, and again, this becomes a starting place for you.”

Section 4: Surface water systems

Section 4 addresses surface water systems, such as lakes, streams, and diversions.

“One of the things we focus on in the handbook is a complete balance: calculating inflows, outflows, and change in storage,” said Mr. Hillaire. “We do have the water budget accounting template, so in this case, change in storage for surface water is fairly straightforward; it’s usually changing reservoir storage. It’s a little more difficult to calculate changes in stream storage, depending on your timestep, but you can calculate all these independently.”

“If you took inflow minus outflow minus change in storage, in theory it should be zero, but usually it’s not, and that’s what we call our mass balance error,” he continued. “What highlighted here, is we do determine that through the water budget accounting template and our information in the report, and that helps you identify how good your balance is or maybe where you need to go back and take a look at it.”

Section 5: Groundwater

The diagram shows the groundwater zone and all the interactions and flows, even water release caused by land subsidence. An important focus of the handbook is using a common vocabulary, so definitions are included, as well as different examples of how to calculate the components.

The handbook also includes tools to help support tracking of managed aquifer recharge.

“Typically, when we put the water into the ground, we need to track that and I think that ability is going to grow as we focus on the management of groundwater supplies, so we want to include a couple of additional components, in addition to groundwater extraction and groundwater export,” Mr. Hillaire said. “That managed water that’s pulled out of a water bank, we call it stored water extraction. If it’s accounted for, you can put the numbers in there. Sometimes that stored water extraction is moved out of the water budget zone. You have the capacity to be able to quantify that and represent that in a total water budget schematic.”

The handbook includes methods on how to calculate change in groundwater storage.

“This helps with calculating all the components of the water budget, to calculate them all independently, and look at the mass balance error to see how well your water budget is represented.”

CASE STUDIES

Sections 6, 7, and 8 present case studies that take the user through the calculation of a water budget. Section 6 is the case study using a non-modeling approach; sections 7 and 8 provide guidance on how to extract water budget components out of existing models.

The case study in Section 6 uses a non-modeling approach to determine the water budget for an area of the Central Valley that includes a mix of irrigation districts and several urban areas, going through the process step by step. The components are computed and entered into the water budget accounting template. Mr. Hillaire noted that in the case study, they added additional categories into the accounting template; the template is a good starting place and flexible enough to allow the user to add more details. It’s also flexible on the timescale as well.

The Section 7 case study demonstrates how to develop a water budget from inputs/outputs of an Integrated Water Flow Model, showing how to pull the information out and put it into the water budget template; the Section 8 case study is the same thing for users of the MODFLOW-OWHM model.

“Sometimes the models will have a tremendous wealth of information but you may want to refine a component or add a component or breakdown, so you can pull all the water model data out and do some further breakdowns when you’re filling in the water budget accounting template,” said Mr. Hillaire. “That’s kind of the flexibility and usefulness we’re trying to provide the user with this tool.”

SECTION 9: DATA RESOURCES DIRECTORY

Section 9 is the data resources directory. It contains all the data sources that the Department is aware of at this time. The hope is that it will be a useful resource for finding the data and resources to make the calculations.

Section 9 is the data resources directory. It contains all the data sources that the Department is aware of at this time. The hope is that it will be a useful resource for finding the data and resources to make the calculations.

“It’s not the end all, but we believe it’s a good starting place,” Mr. Hillaire said. “Sometime in the future, we may envision this as being a living document where more information is provided and shared and becomes a real up to date resources for users in developing water budgets here in California and anywhere.”

The directory as a table with the water budget components listed across the top and the different data resources down the left side; the dots indicate which data sources can be used in which components. That is followed by pages with summaries describing each data source, including the data link and metadata where available.

“We try, if we can, to provide some tips on how to access that data, because we’ve accessed some of that data, so we wanted to share some of our lessons learned in this document to help the user get the most out of this information,” said Mr. Hillaire.

COMMON QUESTIONS

How can the handbook help me if I want to… avoid double counting when creating a water budget?

Section 1 contains a standardized accounting template and common vocabulary that will help ensure no component is counted more than once when compiling a water budget.

How can the handbook help me if I want to… decide whether or not to develop a model to estimate a water budget?

Section 2 contains discussion and flowcharts to help identify what methods would be most appropriate based on your purpose of developing a water budget.

How can the handbook help me if I want to… document the water budget work that I have done, but don’t know what information I should record?

Section 2.12 provides guidance on documenting a water budget to increase understanding and provide for knowledge transfer.

How can the handbook help me if I want to… estimate water budget components?

Sections 3, 4, and 5 provide multiple methods, sources of information, steps, and examples for estimating water budget components.

How can the handbook help me if I want to… find examples of applying the water budget standard accounting template in a physical setting?

Section 6 has an example of developing and documenting a water budget using the standard accounting template for a region in California.

How can the handbook help me if I want to… use one of the two most commonly used integrated flow models in California to develop a water budget?

Sections 7 and 8 have detailed instructions and quick reference tables for how to develop a water budget based on IWFM or MODFLOW-OWHM.

How can the handbook help me if I want to… to develop a water budget but cannot find appropriate data sources for various methods?

Section 9 has a detailed list of resources and a cross-reference table to help you easily identify sources of data for water budget estimation.

WATER BUDGET CONSIDERATIONS IN LIGHT OF THE SUSTAINABLE GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT ACT

Steven Springhorn with the Department’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Office then gave some considerations of water budgets and the water budget handbook in the context of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act or SGMA.

“The Sustainable Groundwater Management Office staff has been coordinating with the water budget staff and we share the view that the process of developing and analyzing water budgets will improve the sustainable management of California’s water resources,” said Mr. Springhorn. “They also support decision making in the basins across the state and improve communication and coordination among water managers within basins and between basins.”

The Handbook for Water Budget Development is part of the Department’s ongoing SGMA planning and technical assistance to GSAs and related entities. Like the many other SGMA datasets, tools, and guidance that DWR has provided, Mr. Springhorn reminded that they are offered as optional resources that GSAs and the public can utilize or not use, and if these tools and guidance materials are used, it does not guarantee approval of a groundwater sustainability plan.

The Handbook for Water Budget Development is part of the Department’s ongoing SGMA planning and technical assistance to GSAs and related entities. Like the many other SGMA datasets, tools, and guidance that DWR has provided, Mr. Springhorn reminded that they are offered as optional resources that GSAs and the public can utilize or not use, and if these tools and guidance materials are used, it does not guarantee approval of a groundwater sustainability plan.

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act defines the water budget requirements and the those requirements are also contained in the groundwater sustainability plan that were created to implement the law and passed back in the middle of 2016. The groundwater sustainability plans require a basin-wide water budget which accounts for groundwater and surface water entering and leaving the basin under historical, current, and projected water budget conditions.

- To read the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act legislation, click here.

- To read the regulations pertaining to water budgets, click here.

“It’s important to note that the GSP water budget requirements are not intended to be a direct measure of groundwater sustainability, but rather the intent is to quantify the water budget in sufficient detail so GSAs can understand their basins and use this information to inform and help guide future projects and management actions in order to achieve the sustainability goal for that particular basin,” said Mr. Springhorn.

He noted there are additional resources related to water budgets in SGMA in the Frequently Asked Questions and also in the section of the handbook titled, “Using this Handbook”

Mr. Springhorn said the Sustainable Groundwater Management Office staff will continue engaging with the water budget team within DWR as well as the GSAs and the public on water budgets by providing regional and statewide data sets, such as statewide land use data, as well as modeling tools, such as the CV2SIM, the model for the Central Valley, which is going through a major upgrade and will be coming out soon.

Mr. Springhorn said the Sustainable Groundwater Management Office staff will continue engaging with the water budget team within DWR as well as the GSAs and the public on water budgets by providing regional and statewide data sets, such as statewide land use data, as well as modeling tools, such as the CV2SIM, the model for the Central Valley, which is going through a major upgrade and will be coming out soon.

“In an effort to continue developing and enhancing these models and modeling tools related to water budgets, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Office is expanding our staff resources and expertise on technical support for modeling, water budgets, surface water groundwater interactions, and climate change so we can continue engaging with GSAs and related entities on these important water budget related topics.”

- Click here for the draft Handbook for Water Budget Development.

- Click here for Frequently Asked Questions about the water budget handbook.

- Click here for the storymap: Comprehensive Water Budget — A Story of Innovations for Water Accounting

- Click here for the water budget accounting templates and other useful information at the CNRA Open Data platform.

- Webinar: Water Budget Handbook – An Interactive Public Webinar on Challenging Water Budget Topics

- Click here for more water budget resources at the Groundwater Exchange.