Kristin Sicke is the Assistant General Manager for Yolo County Flood Control and Water Conservation District, which manages water supplies for 200,000 acres in western Yolo County, which encompasses Woodland, Davis, and the surrounding area. The District manages a small hydroelectric plant, two reservoirs, more than a 150 miles of canals and laterals, and three dams including the world’s longest inflatable rubber dam. In this presentation from the 2019 Western Groundwater Congress, Ms. Sicke describes the District’s efforts to use winter stormwater flows for groundwater recharge in the Yolo subbasin.

“The District has had a long history of implementing policies, programs, and projects that have encouraged us to enhance and protect the knowledge and utilization of our water resources,” she said. “Today I’ll give one example of a policy, a program, and a project that we have implemented that helped us to be in the perfect position to take advantage of this expedited temporary permitting process in the Governor’s executive order. More specifically, I’m going to talk about how we’ve formalized our groundwater recharge program using the Governor’s Executive Order B-36-15 that took place in November 2015 and the State Board’s expedited permitting process for underground storage or groundwater recharge.”

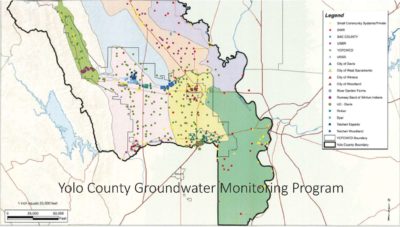

The map shows the watershed. Yolo County’s primary source of agricultural water comes from 50 miles away in Lake County from Clear Lake and the Cache Creek Dam, and the Indian Valley Dam and Reservoir. Water is released from the dams which then flow down Cache Creek into Yolo County.

The map shows the watershed. Yolo County’s primary source of agricultural water comes from 50 miles away in Lake County from Clear Lake and the Cache Creek Dam, and the Indian Valley Dam and Reservoir. Water is released from the dams which then flow down Cache Creek into Yolo County.

“Cache Creek is a very flashy system,” she said. “It can get really peak flows that will attenuate quickly over the next few days, and it’s considered an intermittent stream, so there are times when the creek is not actually connected to the Yolo Bypass.”

As the flows come down Cache Creek, they are diverted at the Capay Diversion Dam and into the District’s canal system. There are two primary canals, the West Adams on the north side and the Winters Canal on the south side. From that, there are 160 miles of canals to distribute the water to farmers.

The canal system is unlined and earthen because the District has realized the benefit from recharging groundwater during the irrigation season. “On average, we recharge about 25% of our irrigation diversions to groundwater recharge, and it has been considered a very successful program by the county and the community and they really appreciate it,” Ms. Sicke said. “But having this policy put us in excellent position to be able to use the earthen canal system during winter events to capture storm flows and to hold it within the canal system for groundwater recharge.”

The canal system is unlined and earthen because the District has realized the benefit from recharging groundwater during the irrigation season. “On average, we recharge about 25% of our irrigation diversions to groundwater recharge, and it has been considered a very successful program by the county and the community and they really appreciate it,” Ms. Sicke said. “But having this policy put us in excellent position to be able to use the earthen canal system during winter events to capture storm flows and to hold it within the canal system for groundwater recharge.”

The Water Resources Association of Yolo County is a consortium of 15+ local agencies that has been around for over 25 years. Early on, they put a lot of emphasis on data and information management, so one of the investments they had made was to develop a water resources information database that has allowed for cooperators within the county, the cities, UC Davis, the mining companies, DWR, the Bureau, USGS, and small community systems to upload and maintain their groundwater monitoring data.

“This was a very effective tool during our GSA formation process and our GSP development because we were able to show all of the groundwater data that we already have been keeping track of, and we were able to show where the data gaps exist,” said Ms. Sicke. “There are over 500 wells in the system and we have data going back to the early 1950s, so it’s a really long record and it’s a really helpful tool as part of our groundwater management.”’

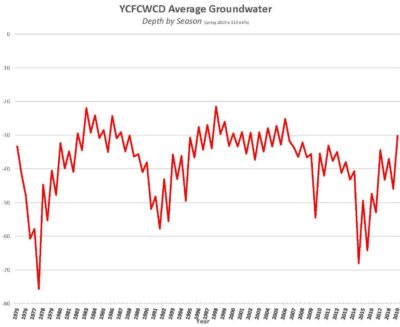

Additionally, the Yolo County Flood Control and Water Conservation District also measures groundwater levels biannually for 150 wells within the district boundaries. The slide (upper, right) shows the hydrograph of average depth to water for those wells, which they have been measuring since the mid-1970s.

“The low points are the measurements that are taken at the end of the irrigation season or in the fall, and the high points are the measurements that are taken at the beginning of the irrigation season or in the spring, so the biggest takeaway from this average data is that the subbasin has historically been able to recover from droughts,” she said, pointing out the drought periods in 1976, 1993, 2009, and 2014-15. “This was another effective tool in forming our GSA and developing our GSP because we’ve been able to talk with stakeholders and the public and let them know that historically, by groundwater levels, we have been sustainable. Since we’ve been able to recover, we credit that to our groundwater recharge program. We like to say that we can continue to be sustainable in the future so long as we are making the investments for groundwater recharge.”

The District also has 16 real time groundwater monitoring wells. The slide shows a snapshot of the District’s SCADA system; the blue lines represent canals and the orange dots represent the real-time groundwater monitoring wells. The system can show comparison trends for each of the wells so that groundwater levels today can be compared relative to previous years with data going back to 2010. Ms. Sicke noted that this is another useful tool for talking with stakeholders and the public about how groundwater levels are doing relative to historical levels.

The District also has 16 real time groundwater monitoring wells. The slide shows a snapshot of the District’s SCADA system; the blue lines represent canals and the orange dots represent the real-time groundwater monitoring wells. The system can show comparison trends for each of the wells so that groundwater levels today can be compared relative to previous years with data going back to 2010. Ms. Sicke noted that this is another useful tool for talking with stakeholders and the public about how groundwater levels are doing relative to historical levels.

“I should note that the SCADA system and the real-time groundwater monitoring wells was one of the things that the State Water Board found extremely helpful during our temporary permit application process,” she said. “The District did not have its own groundwater well, and a big thing they want to make clear with these temporary permits is that the water is being ultimately put to a beneficial use, so if we were not going to be the beneficial user, how would we ensure that the water we were putting in the ground was actually being taken out and put to a beneficial use within a reasonable amount of time? It can’t just stay there to be stored there, as you know. So showing them this SCADA system, they felt confident in knowing that we would be able to show the water that was recharging, but then also show the extraction over time.”

The earthen canals date back to the 1800s, so over the past 15 years, the District has invested millions of dollars in capital projects to modernize the canal system, such as automatic gates and a broadband telemetry system that connects the flow information to their SCADA system. The SCADA system displays the canals and the control sites so they can monitor the flows at certain points in the canal, which helps them to react and respond when necessary.

“It’s extremely useful for our normal irrigation operations, but it is something that when we were talking with the State Water Board, they felt really comfortable knowing that we were going to not only responsibly measure our diversions at the Capay Diversion Dam but that we would also be ensuring that the flows are staying within the canal system and are effectively recharging into the ground,” she said.

In 2015 during the drought, Governor Brown issued Executive Order B-36-15 which directed the water boards to prioritize temporary water right permits to accelerate approvals for capturing high precipitation events during the winter and spring months for groundwater recharge. The Executive Order also exempted CEQA as that can be time consuming; the temporary permitting process is only for 180 days. The provisions were extended again in Executive Order B-39-17.

“We’ve been able to apply every year for the 180-day temporary permit for the past four years, and every year, before we submit the application, we coordinate with the Department of Water Resources and the Bureau to make sure that we are not impacting any downstream senior water rights,” Ms. Sicke said. “We have to make sure the Delta exporters are happy, so if for any reason there is continuity between Cache Creek and the Yolo Bypass during these storm events, we have to make sure the Delta is in excess, so that is something that has to be tracked. We also coordinate with the Department of Fish and Wildlife as we have to maintain live flows a few miles downstream of our diversions at the Yolo Gauge; we have to keep at least 50 cfs in the creek downstream of us. Diversions are allowed through the end of April because the irrigation season generally picks up the beginning of May.”

The District also coordinates with the Central Valley Regional Board, because every year with their application, the District asks to spread some of the stormwater onto farmer’s fields, and the regional water board is concerned about accelerating the nitrogen loading from those fertilized fields and causing nitrate contamination in the groundwater. So far, they have not been spreading the stormwater on fields yet because it takes a lot of coordination and outreach, but it’s something they hope to do in the future.

The District also coordinates with the Central Valley Regional Board, because every year with their application, the District asks to spread some of the stormwater onto farmer’s fields, and the regional water board is concerned about accelerating the nitrogen loading from those fertilized fields and causing nitrate contamination in the groundwater. So far, they have not been spreading the stormwater on fields yet because it takes a lot of coordination and outreach, but it’s something they hope to do in the future.

The District has applied for the 180-day temporary permit for the past four years and has successfully diverted for three of the four years, diverting over 20,000 acre-feet in total. In 2018, the District was unable to divert as there was limited rainfall and lack of excess stormflows. They plan to apply again this next year.

LESSONS LEARNED

Ms. Sicke then turned to the lessons learned. It’s important to know the landscape and hydrology as each watershed is unique, she said. “When we first came to the State Water Board for an application for a temporary permit, we quickly realized they were not expecting us, they were expecting groundwater banking. They didn’t even know much about Cache Creek, so we had to really educate them on the system and its intermittent nature. It took a lot of discussions but it was helpful in the end.”

Make outreach a component of the plan. “This whole program has worked extremely well with our GSA formation and our GSP development that has been taken place in the Yolo Subbasin,” she said. “We talk about this program at every meeting and we are educating the public at every workshop about the value of this. It’s something that we want to make a management action in our GSP, so we just stress the importance of it. We want to apply for a permanent permit eventually.”

Optimize the system while balancing objectives. In order to run this program, there needs to be a perfect storm of sorts where there’s enough rain, the flows are high enough so downstream flows can be met, but then sometimes those rain events can damage the canal system. “Unfortunately last year and in 2017, we did get a lot of damage to our canal systems that limited the amount of water we were able to divert,” she said. “You have to balance construction activities to prepare for the irrigation season coming up, any debris build up. We have to be careful not to take the peak storm flows because they are very sediment-laden and they will plug up the canal system; that was something that we told the State Water Board, even though they envisioned these peak flows, we’d be shaving those off, but we needed to take the tail end as it dies off and the sediment can settle.”

Maximize flexibility to achieve sustainability. “When we went to the State Water Board, we told them we wanted this to be a pilot project and we wanted to come back to them every year and tell them what we learned and how we can make it better, and thankfully that worked out very well,” she said. “They’ve been very responsive and I think they’ve been appreciative that we’ve been taking advantage of this effort. We’re going to apply again this year.”

Featured image: Capay Hills, by Visual Artist Frank Bonilla via Flickr