At the November meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, council members heard a wide range of updates: first, Delta Watermaster Michael George discussed the activities of his office, including implementation of SB-88 and a water rights investigation on Holland Tract; then Council staff briefed the council members on the progress made on the Delta’s climate change vulnerability assessment and adaptation strategy. The Council members were also updated on the efforts of Executive Officer Campbell Ingram and the Delta Conservancy to establish a protocol for carbon sequestration for subsidence reversal projects and managed wetlands on Delta islands, and Delta Protection Commission Executive Officer Erik Vink ran down the latest statistics on Delta agriculture from the update of the agriculture chapter of the Delta Protection Commission’s Economic Sustainability Plan.

At the November meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, council members heard a wide range of updates: first, Delta Watermaster Michael George discussed the activities of his office, including implementation of SB-88 and a water rights investigation on Holland Tract; then Council staff briefed the council members on the progress made on the Delta’s climate change vulnerability assessment and adaptation strategy. The Council members were also updated on the efforts of Executive Officer Campbell Ingram and the Delta Conservancy to establish a protocol for carbon sequestration for subsidence reversal projects and managed wetlands on Delta islands, and Delta Protection Commission Executive Officer Erik Vink ran down the latest statistics on Delta agriculture from the update of the agriculture chapter of the Delta Protection Commission’s Economic Sustainability Plan.

DELTA WATERMASTER UPDATE

Delta Watermaster Michael George gave an update on the activities and initiatives of his office. He began by noting that the organizing principle of his office is really to prepare for times of shortage, as managing a complex water rights system in the Delta becomes most acute in times of shortage, so many of the his activities are focused on that.

Among the issues he discussed was progress on the measurement of diversions as required by SB-88, Term 91 administration, the deterioration in the south Delta, and an initiative to investigate water rights on the Delta islands.

SB-88 implementation: Measurement of diversions

To prepare for the next drought, we need to consolidate the learning from the last drought, and the most important part is engaging with the water community, so the Delta Watermaster’s office has really worked to engage with the folks in the Delta, acknowledging that it is a two-way learning process. The Delta Watermaster’s office has also provided a lot of compliance assistance; regulation of water rights administration in the Delta is changing, so helping the Delta water community to manage compliance has been one of their priorities.

To prepare for the next drought, we need to consolidate the learning from the last drought, and the most important part is engaging with the water community, so the Delta Watermaster’s office has really worked to engage with the folks in the Delta, acknowledging that it is a two-way learning process. The Delta Watermaster’s office has also provided a lot of compliance assistance; regulation of water rights administration in the Delta is changing, so helping the Delta water community to manage compliance has been one of their priorities.

“We have received a lot of support from the Delta community and as I’ve reported to you in the past, we’ve essentially eliminated the failure to file problem as everybody in the Delta filing is explaining to us what they are doing with their water rights and that’s allowed us to move on to QA/QC,” said Mr. George.

“A lot of this is aimed at getting better data so we know and understand and can transparently project to the community and to all water users and all demands, including ecosystem demands, the current state about what we know about water use in the Delta,” he continued. “We also need to look over the horizon to understand and be prepared for what it’s going to mean as these problems all become exacerbated by climate change.”

But when in drought, it’s real-time insight that makes a difference – it’s what is known today about what’s happening in the system that impacts what farmers and export operators do, what the risks to the ecosystem are, and what the regulatory response in times of shortage should be. So Mr. George said he’s trying to focus on projects that produce real-time information to help manage through shortage in the future.

But when in drought, it’s real-time insight that makes a difference – it’s what is known today about what’s happening in the system that impacts what farmers and export operators do, what the risks to the ecosystem are, and what the regulatory response in times of shortage should be. So Mr. George said he’s trying to focus on projects that produce real-time information to help manage through shortage in the future.

One of the tools given by the legislature was SB-88 which required diversions in the Delta to be measured. Mr. George has been working since the law passed in 2015 on figuring out how to accurately measure diversions in the Delta, and he has come to the conclusion that trying to accurately measure every diversion in the Delta is ‘a fool’s errand’.

“I just don’t think we can get there, and I don’t think it’s the right direction to continue to pursue exclusively,” he said. “That doesn’t mean I’m ignoring the legislative direction or the regulations that the water board adopted in order to implement SB 88. One of the problems is that when diversion measurement is pushed down to the managers and controllers of a couple of thousand diversions in the Delta, the maintenance issues and just keeping up with that system is an incredible burden, and there is no practical way to test the accuracy of the data that we get. The information that they do get comes in during the middle of the next irrigation season, so it’s too far outdated to be useful for the management of shortage in the Delta, and there isn’t a lot of confidence in its accuracy.”

Through the Delta Measurement Experimentation Consortium, they have learned a lot about the problems associated with the large number and variability of diversions, the impacts of tides, changing water demands, land uses, and other things. They are now looking at an emerging technology that uses satellite imaging to get consistent, accurate, real-time information that can be used to manage the system.

Through the Delta Measurement Experimentation Consortium, they have learned a lot about the problems associated with the large number and variability of diversions, the impacts of tides, changing water demands, land uses, and other things. They are now looking at an emerging technology that uses satellite imaging to get consistent, accurate, real-time information that can be used to manage the system.

Open ET is a new tool being developed by NASA, Desert Research Institute, and others which utilizes the science of satellite imaging to measure the evapotranspiration of crops and makes it available on a cellphone. Mr. George recently attended a workshop where he saw a demonstration of the ‘minimum viable product’ coming out of the development process. His expectations were far exceeded, and so he invited the people demonstrating the product to come to the next Delta Measurement Experimentation Consortium meeting. At that meeting, they put the product through its paces and were successful at presenting information that the land managers could corroborate with their on-the-ground knowledge.

“I’m excited about this tool,” he said. “We’re going to get a beta version that we can test ourselves. I look forward to maybe in March and April, doing a live demonstration here for you, but that’s the kind of progress that we’re making. I believe we’re going to be in a position where we can get much more actionable accurate high quality consistent data through this tool then through pursuing the fool’s errand.”

The question is how to accomplish that without ignoring the law or the regulations. “Actually, counsel has advised me that number one, we have to demonstrate that strict compliance with the plus or minus 10% is impossible, and then to pursue this as an alternative plan of compliance to get as close as possible,” he said. “The regulation actually allows that to happen, so I proposed to the water board that we do this as a demonstration in the Delta.”

For more information on SB-88, click here.

Term 91

Mr. George then discussed their efforts to improve the administration of Term 91, which is a term that the Water Board has put in every license that’s been granted since 1965. There aren’t many of these licenses in the Delta because most water rights and licenses predate 1965.

Term 91 was put into place to  protect the state and federal water projects when the Delta is in a balanced condition, which is when there is just enough inflow and outflow to keep the Delta fresh and the water quality in balance; this usually occurs in the drier summer months. The way to keep the Delta in balance is that the state and federal projects are required under their licenses to release more water from storage and allow that water to come down to the Delta to maintain that delicate balance. Term 91 is a provision that protects that water from being diverted by someone else as it flows into the Delta to maintain the balance. Mr. George acknowledged it’s a complicated process and so a graph is published to keep everyone and particularly those with Term 91 in their license apprised of conditions.

protect the state and federal water projects when the Delta is in a balanced condition, which is when there is just enough inflow and outflow to keep the Delta fresh and the water quality in balance; this usually occurs in the drier summer months. The way to keep the Delta in balance is that the state and federal projects are required under their licenses to release more water from storage and allow that water to come down to the Delta to maintain that delicate balance. Term 91 is a provision that protects that water from being diverted by someone else as it flows into the Delta to maintain the balance. Mr. George acknowledged it’s a complicated process and so a graph is published to keep everyone and particularly those with Term 91 in their license apprised of conditions.

Earlier this year, the Delta went into trigger conditions, but the projects never asked to invoke the protection. Mr. George said this was due to a combination of factors; there was a lot of water in the system at the time and there were other reasons for releasing water besides maintaining balance in the Delta, therefore the projects on their own volition decided not to seek protection of Term 91.

However, they realized that there had been a lot of turnover in personnel, so everybody wasn’t on the same page in terms of when and how to implement it. Therefore, the Division of Water Rights, Office of Delta Watermaster, and the two water projects decided to tone up this process and essentially automate it and make it available to everybody on a real-time basis, as well as the data behind it.

“The ability to look at a graph like that, but to the extent that you wanted to, to drill down to the data behind it, and that’s the project that we’re working on now with the clear intention of doing this with other water rights administration provisions,” Mr. George said. “The next time these trigger conditions come to bear, we expect to have this toned up and you’ll be able to see a graph like this that’s updated at midnight every night so you’ll be able to see on an ongoing basis when we’re approaching these conditions and therefore when Term 91 maybe triggered.”

Click here for more information on Term 91.

Deterioration in the South Delta

There is a significant problem in the Delta where sediment is building up in the channels; it’s more of an issue in the south Delta where the flows can be low as compared to the northern Delta where there are enough flows to move sediment through the system. When the sediment builds up, it occludes the carrying capacity of the channels and the water gets shallower and warmer, which means more risk of harmful algal blooms, lower dissolved oxygen conditions, and a more hospitable environment for invasive weeds.

The bigger issue is a lot of that sediment is stuck behind dams higher up in the system. The Delta is a sediment-starved estuary, and yet there’s too much sediment in certain places. However, it’s too costly to transport sediment, other than through Mother Nature.

The bigger issue is a lot of that sediment is stuck behind dams higher up in the system. The Delta is a sediment-starved estuary, and yet there’s too much sediment in certain places. However, it’s too costly to transport sediment, other than through Mother Nature.

“The best way to move sediment is to have flowing rivers, streams, and channels, and once you get to this circumstance, your options are very much more expensive and very much more limited to move this anywhere,” Mr. George said. “The only practical place for this sediment to go is on the landside of the levee in close proximity to where it is. But doing that improves channel capacity to move sediment naturally and better through the system.”

He noted that while there are a lot of folks looking at this, he raised the issue at the last Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee meeting as one of the issues the science enterprise needs to consider more than it has in the past.

Climate change and the Delta

The State Water Board as part of the water quality control planning update process is trying to figure out how to correlate voluntary agreements with the biological opinions and the requirements of the Porter Cologne Water Quality Control Act, and all of that while considering climate change.

“It’s time to figure out what we’re going to do about climate change, and so we are all-in at the State Water Board and the Office of the Delta Watermaster with the Stewardship Council’s Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Strategy project, because we believe that’s where these gnarly complex issues need to get worked out so that all of us – all the DPIIC member agencies, all the individuals within the Delta, and the water users in the entire watershed need to have a common understanding from which we can all draw on to make informed decisions about how to deal with climate change.”

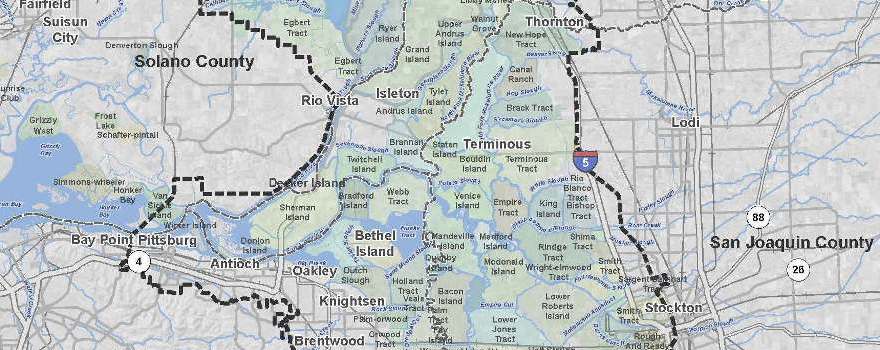

“The Delta is not a black box,” Mr. George continued. “It’s a complex system, and treating it on a mass balance basis where it’s water in and water out misses the complexity that exists, and one of the things that we have to do in the vulnerability assessment and adaptation strategy process is to recognize that the Delta is not a uniform area. It’s 750,000 acres, a lot of people. It’s like the size of the state of Rhode Island. It’s hard to get consensus on big things in the Delta, so we’re really trying to work to get consensus in smaller neighborhood areas to figure out where there are voluntary agreements available with multi-benefits that local people can get involved in and support and help to make improvements.”

The issue of the deeply subsided islands in the Delta is a different issue than the sediment buildup in the South Delta, but it is a localized problem that will probably fall into the laps of the state. The state already owns a large amount of land already, and there’s a substantial risk that some of the deeply subsided islands may not be able to be farmed profitably and may be abandoned.

“That’s a real risk,” Mr. George said. “We’ve seen that happen in the Suisun Marsh where the state almost by default has become the largest landowner and has not been funded to manage that land mass. The only viable strategy today for managing the land mass in the Delta is farming, and if we lose that in certain parts of the Delta, we’re going to have to come up with alternative plans. So I really want to emphasize in all of this that as we look forward to the impacts of climate change, we’ve got to look very much granularly locally at the different situations in the Delta because we could have not a single catastrophic failure, but a continuing cascade of smaller failures that substantially reduce the ecosystem services that we can get from the Delta as well as the water supply and habitat benefits that are there. So there’s a lot at risk and it’s complicated at a local level.”

New initiative: Holland Tract water rights investigation

The Office of the Watermaster has a new initiative which is an investigation of water rights on Holland Tract. Holland Tract was chosen as pilot project because it’s relatively simple; there are only 15 senior water right claims on Holland Tract and the Reclamation District 2025 is cooperative and well managed, he said.

“We think that this is an area where it will give us examples of a lot of the problems, confusion, and inconsistencies we see in water management and reporting,” Mr. George said. “We’re working with the locals there to sort this out, but we’re approaching it to develop it as a protocol template to work through these issues so that we can develop a template for action that we can take to other islands, particularly islands that are in unified management and control.”

“We think that this is an area where it will give us examples of a lot of the problems, confusion, and inconsistencies we see in water management and reporting,” Mr. George said. “We’re working with the locals there to sort this out, but we’re approaching it to develop it as a protocol template to work through these issues so that we can develop a template for action that we can take to other islands, particularly islands that are in unified management and control.”

Holland Tract was formed in 1918; they filed an application for a license with the Water Commission at the time and was ultimately granted a license in 1935 with the priority date of July of 1922. Then there are about 15 other claims of water rights – riparian and pre-1914.

“What we’ve discovered is that first of all, there are a lot of inconsistencies between what clearly happened on the ground and what is reflected in our paper files,” he said. “That’s expected, it was a long time ago, but those differences have compounded over time. So we’re trying to create an accurate database because the records are partly paper files and partly electronic files which are replete with a lot of inconsistent and inaccurate information.”

If we have another drought like 2012-2016, a 1922 water right will be curtailed; it was curtailed in 2014 and again in 2015, so what is the next priority and how do you determine that?

“We didn’t even know enough to send requests for information to many of those water right holders on Holland Tract, and when we did send it, not all of them responded, and those who responded didn’t always respond with accurate information, so what we’re trying to do is drill down, develop a protocol for how you do that, and then putting it in an accessible format that everyone can make sense of,” he said.

“We didn’t even know enough to send requests for information to many of those water right holders on Holland Tract, and when we did send it, not all of them responded, and those who responded didn’t always respond with accurate information, so what we’re trying to do is drill down, develop a protocol for how you do that, and then putting it in an accessible format that everyone can make sense of,” he said.

Mr. George said they anticipate that the project will take about a year. The plan is then to take it to other islands where there is unified ownership and significant interest in understanding their water rights and having their priorities recognized. Over time, hopefully it will be done for every island in the Delta.

Part of the pilot project is to take the data and georeference it and make it available on a cellphone so folks can click down through the various layers and see the information collected. They are also working to make the information accessible in real-time so people can know their water rights and their priorities are because priority is key in times of shortage for determining who gets curtailed when there isn’t enough water in the system. Ultimately the idea is to put it into a common georeferenced database throughout the state of California.

For more information on the Delta Watermaster, click here.

DELTA CLIMATE CHANGE VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT AND ADAPTATION STRATEGY

Assistant Planning Director Harriet Ross gave an update on the climate change vulnerability assessment and adaptation strategy, discussing the study objectives, their progress in the study, key milestones achieved, the technical approach, and the project input that has already been received.

There are four main study objectives: to inform future Delta Plan amendments and implementation, to help the state prioritize future actions and investments, to provide a tool kit of information for local governments to use in their regulatory documents, and to serve as a framework to be built upon by the Council and others in the future.

“Though our process and project are quite comprehensive, we are not able to look at everything, so we really see this as a starting point,” said Ms. Ross. “We are using models and tools that are existing and easily updateable so they can be used by other agencies and our approaches are replicable.”

Steps of the study

There are seven steps to the vulnerability assessment and adaptation strategy process. Steps 1 through 4 represent phase 1 of the vulnerability assessment itself; currently Council staff are at step 3 which is assessing the vulnerability of the critical assets. Subsequent steps will include preparation of an adaptation strategy and will culminate in the development of an adaptation strategy.

There are seven steps to the vulnerability assessment and adaptation strategy process. Steps 1 through 4 represent phase 1 of the vulnerability assessment itself; currently Council staff are at step 3 which is assessing the vulnerability of the critical assets. Subsequent steps will include preparation of an adaptation strategy and will culminate in the development of an adaptation strategy.

Some of the key milestones achieved so far is they have prepared a draft set of resilience goals, synthesized the existing studies, and defined an approach to the analysis. The resilience goals cover five main topics: water, environment, society and equity, economy, and governance. The resilience goals stem from the Council’s coequal goals, the Delta Plan, and the Delta Reform Act and are used to help focus the study and guide their work as they begin to think about adaptation.

Technical approach

They have been working with the Technical Advisory Committee to define the technical approach to the vulnerability assessment itself. For flooding in particular, they are considering the combination of sea level rise from the bay and the instream flows from the rivers, taking into account the shifts in participation that are expected. They are considering the failure from levee overtopping only and analyzing a range of sea level rise scenarios, up to 10 feet in combination with a full range of Delta inflows from the rivers.

For water supply, they have been working closely with the State Water Board and DWR, building upon DWR’s existing model that the Department used to prepare their own vulnerability assessment that was published earlier this year. They will be expanding that analysis to look from 18” to up to 24” of sea level rise, as well as more extreme years of wet and supply conditions.

For the ecosystem analysis, they are building upon the ecosystem amendment, considering the vulnerability of ecosystems on islands that are subject to flooding and within the channel. They are also considering wetlands and the ability to adapt to changing sea levels as well as the vulnerability of ecosystems in current and planned restoration projects. They are also assessing the ability to manage the changes in temperature and salinity and those impacts on aquatic habitat.

For the economics analysis, they are using flood maps to inform the asset exposure, looking at a range of scenarios. The results will determine the economic loss of those assets, the regional economic impact, and allow a comparison of rough estimates of the total economic loss estimated under and across each of those scenarios. Those findings will help us identify the focal points for the adaptation strategy.

They are also considering vulnerable communities, identifying preliminary focus areas through state databases. They are in the process of establishing relationships with community based organizations to help identify additional indicators for consideration in the definition of vulnerable communities in the Delta. They are also engaging with stakeholders and members of the CBOs to help review the findings and analysis of the vulnerable communities.

Opportunities for input and engagement

There are multiple engagement opportunities for the vulnerability assessment. One of them is the stakeholder workgroup created earlier in the summer which is comprised of representatives of the cities, counties, and regional agencies represented in the Delta as well as environmental groups and water districts. Their role is to help us promote the exchange of information between the members and across the stakeholder interests and with their constituents.

The stakeholder workgroup first met in early October. They were asked a series of questions to help prepare the vulnerability assessment that would be utilized by other entities; some of the questions and the range of responses are on the slide.

The stakeholder workgroup first met in early October. They were asked a series of questions to help prepare the vulnerability assessment that would be utilized by other entities; some of the questions and the range of responses are on the slide.

Another opportunity for input is through the Technical Advisory Committee. The TAC was established at the beginning of the project. Their role is to provide expert knowledge, document review, and guidance on the methods for the study from big picture to fine scale advice on their approach and shared the data and tools being used in the analysis.

There are outreach opportunities through the Council meetings themselves. They are working to partner with existing agencies and groups undergoing their own processes related to vulnerability assessments, holding small informal briefings with groups that have asked for more information, and they are preparing an approach for outreach to vulnerable communities.

Council staff is currently preparing the draft vulnerability assessment, and after the public review, they will review the findings with the Council. The next step after that will be to finalize the vulnerability assessment and then to begin the adaptation strategy itself.

Councilmember Oscar Villegas asked for more details on the governance goal.

Executive Officer Jessica Pearson noted that what’s unique about this project is while they are trying to inform the Council’s work on the Delta Plan and other state activities, they are also trying to partner with local agencies to make sure the vulnerability assessment provides the kind of data that they are increasingly being required to put into their local plans.

“We want to make sure that the local governments will find it useful and be able to use it to update their regulatory documents,” said Harriet Ross. “For example, the first question that we asked was how does your organization plan to use the vulnerability assessment, and we received a broad range of responses, including from informing investments to SB 379 compliance which is a requirement for local agencies to address climate change adaptation and resiliency in their own regulatory documents. We heard about the use of our information from forming local policies; they want to compare to existing analyses that they have done because a number of agencies have prepared their own vulnerability assessments so they want to see what we’ve done and how it’s different from their findings.”

DELTA CONSERVANCY UPDATE

Campbell Ingram, the Executive Officer of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Conservancy, updated the Council on their Prop 68 Community and Economic Enhancement Grant Program and the Conservancy’s efforts to establish a carbon market for the Delta.

Prop 68 grant program

The Prop 68 Community and Economic Enhancement Grant Program authorized $12 million for the Delta Conservancy to fund projects in the areas of recreation and tourism, historic and cultural preservation, and environmental education. Mr. Ingram noted this is the first block of funding that the Conservancy has had for the second half of the Conservancy’s mandate which is Delta as a place. He anticipates board approval in December with the solicitation opening up in January of 2020

Mr. Ingram said that it’s not an open solicitation; projects and ideas can come to them with a high-level concept proposal and if it meets certain criteria, the Conservancy will enter into a partnership with the applicant and then work through with that project to develop a full proposal that they can then take to the board for funding approval.

“We are very hopeful,” he said. “It’s a relatively small amount of money, but through this process, we’ll be able to strategically fund projects that have real significance and can actually benefit the Delta as place.”

Managed carbon wetlands in the Delta

Mr. Ingram noted that subsidence is an issue in some areas of the Delta; there is also enormous carbon emissions coming off of the Delta because of the oxidation of peat soils. So the Delta Conservancy has been working for the past several years to develop a protocol and a market based incentive for converting lands from agricultural production to managed wetlands and/or rice production which would stop subsidence and stop the emissions; if those emissions could be quantified, they could take that to the voluntary market and develop a revenue stream.

The Conservancy is nearing completion of third-party verification of the emission reductions for three separate projects totaling about 1600 acres of wetlands on Sherman and Twitchell islands on land owned by the Department of Water Resources.

“It’s a requirement of the protocol that someone from outside the process verify the emission reduction expectation and certify the credits are available for those projects,” said Mr. Ingram. “Once that process is complete, DWR will have the option to retire those credits or take those credits to market and sell those credits and generate a revenue stream for the practice. It is the first use of the protocol and it will be a great example to other landowners about how a revenue stream can result from carbon management in the Delta. Our expectation is that that incentive will continue to grow and hopefully in the near term, it can compete with the commodities that are grown in the Delta and be a viable option for public and private landowners to consider changing their land practices and still be economically viable.”

Councilmember Mike Gatto noted that carbon prices can fluctuate significantly. Have you modeled what the profits per acre or something comparable to commodity pricing?

Campbell Ingram said they’ve done quite a bit of that, which includes working with carbon financiers who are engaged with those who are buying credits on the voluntary market to think very critically about what the price point could be. “Right now in the voluntary market, we’re convinced we could get $7 per credit or ton. That will net in the Delta, based on the amount that’s coming off the Delta and what you can quantify, somewhere close to $60 per acre per year. That exceeds most of the current leased values in the deeply subsided Western Delta, but it’s not quite competing with commodities.”

“The next step is to get that protocol adopted into ARB’s compliance program, and that could take another year and a half to two years,” Mr. Ingram continued. “There’s interest doing that, but that gets the carbon price up to about a $19 price point, which gets you closer to $180 net per acre in the deeply subsided Western Delta. Our understanding is that there’s a sweet spot or expectation spot of about $150-160 in return for current commodities. There’s a lot of variability, so currently we can replace lease value for those organizations that are leasing back to farmers, but hopefully in the future we’re exceeding that. There’s also been speculation that the carbon market is likely to go to a $30 price point, in which case you’re over $300 net per acre. It’s promising. It looks like there is a path forward that can stop subsidence and keep people economically viable.”

“The other thing I’ll mention is that there’s about 50,000 acres in this zone that are publicly owned or publically financed, so those are viable alternatives for those public agencies to have a revenue stream to have O&M in perpetuity for those islands and to be able to manage those islands differently.”

Councilmember Ken Weinberg asked if deeply subsided means a limited horizon for profitability and being able to continue in commercial agriculture?

“One of our objectives is to stop the subsidence for the risks to water supply and for carbon, but also, that subsidence continues to threaten the economic viability of the region,” said Mr. Ingram. “There are many places in the Delta where they are continuing to burn through the peat and you’re getting lenses where water coming through the sand lens below and making large areas of these islands too wet to farm, so essentially you’re looking for alternatives for declining economic viability as well as increasing risks to water supply. There are truly astounding carbon emissions coming off of this very small area within the Delta.”

For more information on the Delta Conservancy, click here.

DELTA PROTECTION COMMISSION

Erik Vink, Executive Officer of the Delta Protection Commission, then updated the Commission on agriculture in the Delta and an update on the Delta’s designation as a National Heritage Area.

He began by saying that he’s encouraged by Campbell Ingram’s work regarding alternatives for the deeply subsided parts of the Delta. “If that can become a viable option for private landowners, and we think it needs to be demonstrated to be a viable option with the publicly owned lands or the publicly financed lands before we can really demonstrate that to private landowners, but that would be a very encouraging outcome for that deeply subsided part of the Delta,” he said.

Economic Sustainability Plan: Update to agriculture chapter

The Commission is in the process of updating the Economic Sustainability Plan. The update is being done in chapters, with the agriculture chapter the first to be updated, recognizing the critical importance of agriculture to the Delta economy. Dr. Jeff Michael has been working on the update, and he’s progressed far in that work; they are in the early stages of updating the recreation and tourism chapter, the second-most important component of the Delta economy.

Mr. Vink then presented some of the information from the agriculture update, noting that the crop information is from 2016 and is derived from county ag commissioner crop reports and information from Land IQ. He started with crops being grown in the Delta, noting there have been some significant changes.

“What’s happening in the Delta is not dissimilar to what’s happening throughout California agriculture,” he said. “There’s a move to higher value, more intensive crops, so the big acreage increases are in almonds and wine grapes. There’s almost a corresponding decrease in corn production. Corn is the mainstay crop in the Delta; it’s significant and important to the more subsided parts of the Delta, but 2009 was a high water mark for corn prices so a lot of production went in. Corn has fallen in value, and as a result, we’ve seen a significant decrease in corn planting in the Delta.”

He also noted that asparagus, an iconic Delta crop, is off the list. It’s a very labor intensive crop and as a result, it’s fallen off the map in the Delta and throughout California which is indicative of trends statewide in agriculture in California, he said.

The next charts show the additional vineyard and almond acreage between 2011 and 2016.

The maps show where the vineyards and almonds have been planted. The almonds are in the southeast corner of the Delta region and up in the northwest corner up into Solano County.

Mr. Vink presented a table of the top crops by revenue, pointing out that wine grapes are the big economic driver for Delta agriculture with processing tomatoes coming in second by about half, and those two crops combined with corn and alfalfa really make up the bulk of Delta agricultural production.

Mr. Vink presented a table of the top crops by revenue, pointing out that wine grapes are the big economic driver for Delta agriculture with processing tomatoes coming in second by about half, and those two crops combined with corn and alfalfa really make up the bulk of Delta agricultural production.

“When you add it all together, we’re at nearly a billion dollars of farm gate value, which means the value of products that leave Delta farms,” he said. “Almost all of that is in crop production, but we do have some animal products in the Delta as well.”

He presented his summary slide, and gave his conclusions. “I don’t know how much more we will see wine grapes in the Delta,” he said. “When you look at where those permanent crops are occurring, it’s not in the more deeply subsided parts of the Delta as that’s problematic for higher value crop production, but certainly at the periphery of the Delta and we’re going to continue to see that. The last two bullets just summarize some of the information coming out of running this data through the economic model that estimates economic impact and jobs, clearly important for us in the Delta region, and the job impact is that production spools out throughout the state of California.”

He presented his summary slide, and gave his conclusions. “I don’t know how much more we will see wine grapes in the Delta,” he said. “When you look at where those permanent crops are occurring, it’s not in the more deeply subsided parts of the Delta as that’s problematic for higher value crop production, but certainly at the periphery of the Delta and we’re going to continue to see that. The last two bullets just summarize some of the information coming out of running this data through the economic model that estimates economic impact and jobs, clearly important for us in the Delta region, and the job impact is that production spools out throughout the state of California.”

Delta National Heritage Area

Next, Mr. Vink gave a brief update on the Delta National Heritage Area. In February of 2019, the Delta National Heritage Area was enacted into law. The Delta Protection Commission is responsible for developing the management plan and overseeing the National Heritage Area. By statute, the Commission has three years to complete that activity; if not completed by then, the federal funding stream will end. The Commission is about to approve a contract for preparation of the project plans and to compile the components of the mandated Delta Heritage Area management plan.

For more information on the Delta Protection Commission, click here.

FOR MORE INFORMATION …

- For more information on the Delta Stewardship Council, click here.

- For the agenda for the November meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, click here.

- To watch this meeting on webcast, click here.

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!