San Clemente Dam, Klamath Dams, and Matilija Dam removal spotlighted at ACWA Conference

The time, expense, and regulatory uncertainty of providing viable and effective fish passage have propelled reservoir operators to pursue dam removal in watersheds throughout the state. The Caramel River Reroute and the San Clemente Dam Project is the largest dam removal project ever to occur in California to date.

Next year, the largest dam removal project in U.S. history is set to begin on the Klamath River. As fish populations dwindle and legacy hydroelectric and water supply facilities age, this trend is sure to continue.

The pace of dam removal has been accelerating across the country. Since the 1970s, 1400 dams have been removed, 82 in the last year alone. California led the nation in dam removals in 2018 with 35 different projects across the state. These aging dams are degraded, full of sediment and they no longer provide the intended flood control, water supply, hydropower and economic benefits, and they almost always block or degrade valuable habitats for threatened and endangered species.

At the spring conference of the Association of California Water Agencies, a panel discussed three dam removal projects: the completed San Clemente Dam removal project, the Klamath Dam removal project set to begin next year, and the Matilija Dam removal project which is still in the planning phases.

On the panel:

Jeff Szytel, founder and principal of Water Systems Consulting, presented on the San Clemente Dam removal project. Mr. Szytel is a professional engineer with over 18 years of experience in civil and environmental engineering specializing in water, wastewater, recycled water systems, project and program management, construction management, capital improvement planning, water and wastewater treatment facilities, optimization design, hydraulic design, and pilot studies.

Mark Bransom, Chief Executive Officer of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation. He has over 20 years of planning, engineering, and construction experience in water resources and environmental management from state and local governments, federal agencies, tribal nations, NGOs, and private sector clients throughout the United States. Mr. Bransom was formerly with CH2M Hill as senior vice president in water resources and environmental management where he oversaw a large variety of water infrastructure and environmental restoration projects.

Peter Sheydayi is the Deputy Director for Design and Construction for Ventura County Watershed Protection District and he has been working on the Matilija Dam Removal Project since 2004. He has over 30 years of water resource engineering experience, 19 of which have been with the water protection district in Ventura.

CARMEL RIVER REROUTE AND SAN CLEMENTE DAM REMOVAL PROJECT

The San Clemente Dam was located on the Carmel River in Monterey County approximately 18.5 miles from the mouth at the Pacific Ocean. Cal American Water is an investor-owned utility and owner of the dam.  The $83 million project was a public-private partnership between Cal American Water, the National Marine Fisheries Service, and the Coastal Conservancy. The San Clemente Dam removal project is the largest dam removal project in the history of California – for now.

The $83 million project was a public-private partnership between Cal American Water, the National Marine Fisheries Service, and the Coastal Conservancy. The San Clemente Dam removal project is the largest dam removal project in the history of California – for now.

The San Clemente Dam was built in 1921. It was a 106-foot tall thin arch concrete dam and was important for diversions from the Carmel River that supported economic development of the Monterey Peninsula for generations after its completion. The dam had a fish ladder added for steelhead, but it wasn’t in an effective location, and was relatively steep and long, thus severely impairing passage for steelhead.

In addition to being a barrier to fish passage, there were several other factors that ultimately contributed to the demise of San Clemente Dam. In the early 1990s, the California Department of Water Resources’ Division of Safety of Dams issued a safety order for the dam structure, determining that the structure could potentially fail in a maximum credible earthquake or probable maximum flood.  Additionally, more than 2.5 million cubic yards of sediment have been trapped behind the dam, and less than 5% of the storage volume of the reservoir remained. Then, as if to emphasize the risk, the dam was dramatically overtopped by flood flows in the spring of 1995.

Additionally, more than 2.5 million cubic yards of sediment have been trapped behind the dam, and less than 5% of the storage volume of the reservoir remained. Then, as if to emphasize the risk, the dam was dramatically overtopped by flood flows in the spring of 1995.

The dam was no longer used the dam for diversion of water from the Carmel River, and it was clear that the San Clemente Dam had reached the end of its useful life. Strengthening the dam would resolve the public safety issues, but would not address the other issues that the dam was causing, such as impaired access for steelhead to upstream spawning and rearing habitat, the disconnection of the riparian ecology along the Carmel River, and the disruption of sediment transport down to San Clemente Beach and the estuary. Removing the dam would resolve these issues and provide significant benefits to both steelhead and California red legged frog. For these reasons, the California State Coastal Conservancy,  the National Marine Fisheries Service, and the Planning and Conservation League Foundation worked with Cal Am to develop a feasible approach to cooperatively implement the dam removal option.

the National Marine Fisheries Service, and the Planning and Conservation League Foundation worked with Cal Am to develop a feasible approach to cooperatively implement the dam removal option.

In December of 2007, the California Department of Water Resources certified the final EIR/EIS, and indicated that the dam safety issue could be addressed through implementation of the dam removal project.

As with any dam removal project, there isn’t really a straightforward option. The site was remote, the downstream watershed was developed, and sediment management was a principal concern.

REMOVING THE DAM

The project was envisioned to be implemented in a series of five steps:

Step 1: Drain the reservoir. First, the Carmel River was temporarily diverted into a pipeline around the project site and the reservoir was dewatered to allow construction access to the Carmel River and San Clemente Creek.

Step 1: Drain the reservoir. First, the Carmel River was temporarily diverted into a pipeline around the project site and the reservoir was dewatered to allow construction access to the Carmel River and San Clemente Creek.

Step 2: Excavate the sediment. The sediment was excavated from San Clemente Creek channel and the area immediately upstream of the dam and deposited in a sediment stockpile in the Carmel River channel.

Step 2: Excavate the sediment. The sediment was excavated from San Clemente Creek channel and the area immediately upstream of the dam and deposited in a sediment stockpile in the Carmel River channel.

Step 3: Re-route the river. Then a permanent reroute channel was blasted through the drainage divide that separated the Carmel River from San Clemente Creek. A diversion dike was built upstream of the sediment stockpile to permanently force the Carmel River flows into the San Clemente Creek channel. The sediment stockpile was stabilized in place with an engineered stabilized sediment slope at its downstream end. A series of engineered step pools were constructed to facilitate low flow fish passage through the project site and to provide hydraulic stability.

Step 3: Re-route the river. Then a permanent reroute channel was blasted through the drainage divide that separated the Carmel River from San Clemente Creek. A diversion dike was built upstream of the sediment stockpile to permanently force the Carmel River flows into the San Clemente Creek channel. The sediment stockpile was stabilized in place with an engineered stabilized sediment slope at its downstream end. A series of engineered step pools were constructed to facilitate low flow fish passage through the project site and to provide hydraulic stability.

Step 4: Restore the river: The various habitat areas were graded, planted, and irrigated. The restored river reach included seed boulders, overbank protection including large woody debris, and various riparian wetland habitats.

Step 4: Restore the river: The various habitat areas were graded, planted, and irrigated. The restored river reach included seed boulders, overbank protection including large woody debris, and various riparian wetland habitats.

Step 5: Take out the dam. Finally, the dam was removed in 5 phases. Mr. Szytel noted that this was the easiest part. A ramp was built, the excavator drove up with hydraulic hammers and broke the dam apart in pieces, then hauled off those pieces for permanent disposal within the sediment stockpile.

Step 5: Take out the dam. Finally, the dam was removed in 5 phases. Mr. Szytel noted that this was the easiest part. A ramp was built, the excavator drove up with hydraulic hammers and broke the dam apart in pieces, then hauled off those pieces for permanent disposal within the sediment stockpile.

LESSONS LEARNED

Mr. Szytel then turned to lessons learned, distilling it down to four basic things: Build a committed team, understand and actively manage the risk, embrace criticism, and design for uncertainty. He spoke about each of these in turn.

First and foremost, it takes a committed team.

No single person or no single agency can pull off a complex project like this on their own, he said. “We had a core team of three organizations and another six that were regularly involved. All nine of those organizations were repeatedly asked to work outside of their comfort zone. This required agreement on the project concept and overarching project goals; we needed to return to these goals over and over when faced with difficult decisions. The commitment and engagement of high level leadership in each organization – I can’t stress that enough. When the project level team got into a bind, we could turn to our executive leaders and they would provide us the support we needed to keep the project moving. The mutual commitment of resources, primarily including staff and money among the participating agencies, and perhaps most importantly, trust. Without it, this project would have taken much longer and cost much more money to implement. We would have been bogged down with disputes, finger pointing, delays, and eventually even litigation.”

No single person or no single agency can pull off a complex project like this on their own, he said. “We had a core team of three organizations and another six that were regularly involved. All nine of those organizations were repeatedly asked to work outside of their comfort zone. This required agreement on the project concept and overarching project goals; we needed to return to these goals over and over when faced with difficult decisions. The commitment and engagement of high level leadership in each organization – I can’t stress that enough. When the project level team got into a bind, we could turn to our executive leaders and they would provide us the support we needed to keep the project moving. The mutual commitment of resources, primarily including staff and money among the participating agencies, and perhaps most importantly, trust. Without it, this project would have taken much longer and cost much more money to implement. We would have been bogged down with disputes, finger pointing, delays, and eventually even litigation.”

He acknowledged it took several years to get the project team committed. The basic deal framework was that Cal Am would pay $49 million of the project cost, equivalent to the costs of strengthening the dam in place, and the rest of the money would be raised by the state Coastal Conservancy and the National Marine Fisheries Service. When the project was completed, Cal Am would donate the 920-acre property to the Bureau of Land Management.

“It’s interesting because the basic deal terms came together relatively smoothly, but it turned out that those really weren’t the key obstacles to moving the project forward,” he said.

Understand and manage risk

The second key success factor is effective risk management. “The single biggest obstacle we faced in moving the project into construction was fear of liability,” he said. “It was an unprecedented project that had never been implemented in California at this scale. The key fears among the project team were liability in general, what could go wrong, and who would pay for it. To get over that hump, we needed to understand the risks, identify which ones which are really important, then find ways to reduce and manage those risks.”

The second key success factor is effective risk management. “The single biggest obstacle we faced in moving the project into construction was fear of liability,” he said. “It was an unprecedented project that had never been implemented in California at this scale. The key fears among the project team were liability in general, what could go wrong, and who would pay for it. To get over that hump, we needed to understand the risks, identify which ones which are really important, then find ways to reduce and manage those risks.”

There was a lot of uncertainty. Most of the restoration site was buried under sediment up to 90 feet deep and they weren’t sure what they would find when they started excavating. Cal Am had never implemented a large scale habitat restoration project like this, and was afraid the regulatory liabilities that they would be taking on. Additionally, this was a new partnership and it had yet to be fully tested. And cost overruns – what could cause them and who would pay?

A risk assessment was prepared to understand the relative risk profile of dam strengthening versus dam removal. “The initial concern was that dam removal was a riskier project, but a comprehensive risk analysis showed that dam removal was actually a lower risk project,” he said. “This was a big ‘aha’ moment, especially for Cal Am. The risk assessment helped to identify where we needed to implement strategies to reduce or mitigate risk and gave all partners a better understanding of what we were all getting into. It also helped lead us into a number of key decisions, notably the decision to go with the design-build project delivery method.”

A risk assessment was prepared to understand the relative risk profile of dam strengthening versus dam removal. “The initial concern was that dam removal was a riskier project, but a comprehensive risk analysis showed that dam removal was actually a lower risk project,” he said. “This was a big ‘aha’ moment, especially for Cal Am. The risk assessment helped to identify where we needed to implement strategies to reduce or mitigate risk and gave all partners a better understanding of what we were all getting into. It also helped lead us into a number of key decisions, notably the decision to go with the design-build project delivery method.”

Embrace criticism

The third key success factor is to embrace criticism. “This may seem counterintuitive but the bottom line is the more eyes you have on your project, the better your project will become,” said Mr. Szytel.  “I want to caveat that with embracing criticism with strong leadership; that is, being open to that feedback but really sticking to the goals and values of the project as your guide.”

“I want to caveat that with embracing criticism with strong leadership; that is, being open to that feedback but really sticking to the goals and values of the project as your guide.”

The project embraced technical criticism through a Technical Review Team comprised of academics, consultants, and community-based experts who were paid to ensure their full attention and input to the process. They also worked with the Bureau of Reclamation to have them do a DEC or Design, Estimating, and Construction technical review of the project which included a value engineering review and risk assessment of the preliminary design.

They also quite literally embraced criticism in public meetings as well. “One of my favorite public meetings of all time was at the Kashawa General Store where they handed out refreshments and beer and go everyone fed and fully lubricated before we gave our presentation, which made for a pretty interesting environment,” said Mr. Szytel. “The local community was concerned. They didn’t like the route that was designated in the environmental impact report for accessing the site, because of the potential impacts to their community and they were pushing hard. We felt as though the analysis from the EIR showed that the access they wanted really wasn’t feasible, but as we opened our minds to their ideas, we realized that their route was feasible and we did some additional work, and it actually improved the project because of that feedback.”

Design for uncertainty

Ecological restoration by its very nature comes with large uncertainties, and for a restoration project to be resilient, you need to account for those uncertainties in the design. “A few key recommendations we found are, one, to remember that models are just estimates,” Mr. Szytel said. “Design criteria for any critical components should be conservative to account for model uncertainty and not just model uncertainty, but natural variability. Develop plans to address the uncertainties of constructability and procurement. Consider what failure might look like and develop a design that will be resilient, even if it fails. And incorporate appropriate contingencies into to cost estimates and fund raising.”

Mr. Szytel said that they were tested with uncertainty frequently throughout the project, most significantly in the first summer after project completion, when a wildfire burned a large portion of the upper watershed, and then the following February, a 30 year flood roared down the river and completely reorganized the channel.

Mr. Szytel said that they were tested with uncertainty frequently throughout the project, most significantly in the first summer after project completion, when a wildfire burned a large portion of the upper watershed, and then the following February, a 30 year flood roared down the river and completely reorganized the channel.

“It did pretty much what we hoped it would,” he said. “It recreated steps and pools and boulder cascade and plain bed reaches. I think the biggest challenge for us was although the rearranged channel does not meet all of the fish passage design criteria specified by the regulatory agencies, it has a much higher diversity of routes, particularly for juvenile fish, and can pass fish at flows comparable to other reaches of the river. So wonderfully amazingly, no one was pushing to reconstruct that beautiful chain of step pools. The river is still evolving, and we will be learning about it for years to come, so don’t be surprised if you hear about it at future conferences.”

PROJECT OUTCOMES

Post-project habitat surveys last year identified Pacific lamprey in the restored channel and even captured video of them building a nest in the channel bottom. Prior to dam removal, Pacific lamprey were completely isolated from the upper reaches of the river as they could not pass the fish ladder at San Clemente Dam.

Even more encouraging are the recent fish counts. “Steelhead numbers are up dramatically at Los Padres Dam, and so far this year 123 adult fish have been counted there; for comparison, there were only 7 adult fish counted in 2017, and 29 in 2018,” he said. “Steelhead eggs hatch in three to four weeks and juvenile steelhead typically spend one to two years rearing in fresh water before they migrate into the ocean to feed and mature. Steelhead can remain at sea for up to three years before returning to freshwater to spawn. Since the dam was removed in 2015, we would expect to see numbers of adults rising due to removal of the dam in four to five years, and it looks like they are right on time. We are all optimistic about continued rise in the number of steelhead.”

Even more encouraging are the recent fish counts. “Steelhead numbers are up dramatically at Los Padres Dam, and so far this year 123 adult fish have been counted there; for comparison, there were only 7 adult fish counted in 2017, and 29 in 2018,” he said. “Steelhead eggs hatch in three to four weeks and juvenile steelhead typically spend one to two years rearing in fresh water before they migrate into the ocean to feed and mature. Steelhead can remain at sea for up to three years before returning to freshwater to spawn. Since the dam was removed in 2015, we would expect to see numbers of adults rising due to removal of the dam in four to five years, and it looks like they are right on time. We are all optimistic about continued rise in the number of steelhead.”

“So in conclusion, we’ll continue to learn from the San Clemente Dam Removal Project for years to come, and it stands as an important milestone in the evolution of river management in the West,” he said.

KLAMATH DAMS REMOVAL

The Klamath River flows 257 miles through Oregon and northern California in the United States, emptying into the Pacific Ocean near the small community of Klamath in Northern California. The Klamath is a working river and its stressed; fisheries and water quality have been in decline for decades.

The Klamath River flows 257 miles through Oregon and northern California in the United States, emptying into the Pacific Ocean near the small community of Klamath in Northern California. The Klamath is a working river and its stressed; fisheries and water quality have been in decline for decades.

Mark Bransom is the Chief Executive Officer of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC), which is a 501c3 non-profit governed by a 14-member board of directors appointed by the signatories to the amended Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement or the KHSA. The Klamath River Renewal Corporation was formed to take ownership of four PacifiCorp dams — JC Boyle, Copco, No. 1 & 2, and Iron Gate — and then remove these dams, restore formerly inundated lands, and implement required mitigation measures in compliance with all applicable federal, state, and local regulations. He noted that since the KRRC was created explicitly for the purpose of removing the dams and restoring volitional fish passage and a free flowing river, they not authorized to consider alternatives to dam removal.

THE HISTORY OF THE PROJECT

PacifiCorp’s annual license under the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to operate the Klamath Project expired back in 2006. They have continued to operate on a series of annual renewals of that license. In 2010, two agreements were negotiated: the original Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement which was focused primarily on dam removal and the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement, which created funding for restoration, land transfer, and other things. The combination of those two agreements was intended to address comprehensive solutions for the Klamath Basin.

PacifiCorp’s annual license under the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to operate the Klamath Project expired back in 2006. They have continued to operate on a series of annual renewals of that license. In 2010, two agreements were negotiated: the original Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement which was focused primarily on dam removal and the Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement, which created funding for restoration, land transfer, and other things. The combination of those two agreements was intended to address comprehensive solutions for the Klamath Basin.

Congressional approval was required for the two agreements, but due to inaction at the end of 2015, the KBRA sunset. In early 2016, the parties to the KHSA got back together and decided to go through a standard FERC process to transfer and surrender the hydroelectric license to a non-profit entity who would be the entity responsible for dam removal, hence the formation of the KRRC as this approach does not require Congressional approval.

PAYING FOR THE PROJECT

There are four hydroelectric dams that are part of the Lower Klamath Project: JC Boyle, Copco #1, Copco #2, and Iron Gate Dam. The dams are not operated for flood control or for water diversions; they operate as run of the river dams to build head to spin turbines to produce electricity. The four dams have a combined rating of about 165 megawatts; they are currently producing an annual average of about 65-70 megawatts, which is less than 2% of PacifiCorp’s portfolio. PacifiCorp has already replaced the power through other green sources, so there is no loss in sustainable energy by removal of the dams.

There are four hydroelectric dams that are part of the Lower Klamath Project: JC Boyle, Copco #1, Copco #2, and Iron Gate Dam. The dams are not operated for flood control or for water diversions; they operate as run of the river dams to build head to spin turbines to produce electricity. The four dams have a combined rating of about 165 megawatts; they are currently producing an annual average of about 65-70 megawatts, which is less than 2% of PacifiCorp’s portfolio. PacifiCorp has already replaced the power through other green sources, so there is no loss in sustainable energy by removal of the dams.

The estimate for removal of the four dams is $450 million, $200 million of which comes from a surcharge on PacifiCorp monthly bill. The surcharge will continue until a total of $200 million is accrued. The balance of the funding – up to $250 million – comes from Prop 1.

The estimate for removal of the four dams is $450 million, $200 million of which comes from a surcharge on PacifiCorp monthly bill. The surcharge will continue until a total of $200 million is accrued. The balance of the funding – up to $250 million – comes from Prop 1.

“I am continually reminded by California that it’s up to $250 million, they would like to see us spend less,” said Mr. Bransom. “If we can keep it under the $250 million from Prop 1 we will do so, but that’s not my primary goal is to do it for less than $450 million. I’m capped, so I am a capitalized non-profit subject to FERC regulation.”

PacifiCorp agreed to dam removal because their early estimates for the cost of implementing fish passage and water quality improvements under FERC relicensing scenario ran to a minimum of $450 million and easily could have gone to a billion, so the PUC found that implementation of the KHSA was in the best interests of Pacific Corps customers.

REMOVING THE DAMS AND RESTORING THE RIVER

Mr. Bransom presented the schedule (as it was in May), noting it was subject to change. So far, the work of the KRRC has been focused on preliminary design and permitting, including engtering into a preliminary services contract with Keweit design-build entity.

Mr. Bransom presented the schedule (as it was in May), noting it was subject to change. So far, the work of the KRRC has been focused on preliminary design and permitting, including engtering into a preliminary services contract with Keweit design-build entity.

“I learn every day there are things that I can control and things I can’t control,” he said. “It is going to take us as many if not more permits to take these four dams down than it will take to build Sites Reservoir if it gets built.”

Under the current scenario, there is the FERC process for license transfer and license surrender; they are still waiting for a decision from FERC and they have no idea how long it will take them to make the decision. So they have the contractor ready to get out in the field for early work with the goal of being able to initiate drawdown of the reservoirs in January of 2021, followed by dam removal in 2021- 2022.

“That schedule is subject to revision because the FERC process, including the independent review being done by the Board of Consultants on virtually every element of our work, and our ability to address some of the fundamental tenets of the KHSA including providing indemnification for the states and for Pacific Corp – all are literally breaking some new ground and could simply run us into a little bit longer schedule.”

There are a number of major components to the project. There is a water line for the city of Yreka at the bottom of Iron Gate Reservoir which will need to be relocated prior to drawing down the reservoirs. They will need temporary construction access and to make permanent transportation improvements. They will have to address downstream flood control; there are about 2 dozen properties identified in the 18 mile reach below Iron Gate that are subject to increased flood risk, so they will be elevating and building levees, buying out flood easements, and other solutions for those properties.

There are a number of major components to the project. There is a water line for the city of Yreka at the bottom of Iron Gate Reservoir which will need to be relocated prior to drawing down the reservoirs. They will need temporary construction access and to make permanent transportation improvements. They will have to address downstream flood control; there are about 2 dozen properties identified in the 18 mile reach below Iron Gate that are subject to increased flood risk, so they will be elevating and building levees, buying out flood easements, and other solutions for those properties.

They will have to make modifications to the hatchery at Iron Gate Dam. The hatchery was required mitigation for Iron Gate Dam construction and it’s a required mitigation for dam removal. The current hatchery plan will require work at the hatchery at Iron Gate Dam as well as retrofits and upgrades at the Fell Creek Hatchery. The Iron Gate Hatchery draws water from the Iron Gate Reservoir so they will have to provide a replacement water supply and have those hatcheries operational before the reservoirs are drawn down.

There are old gates on the upstream side of the original construction diversion tunnels; they are going to replace those gates and drill out the concrete that was placed in the tunnels when the dams were completed, line those tunnels, and use them for the drawdown of the reservoir.

There is about 15 million cubic yards of sediment behind the four dams; they anticipate that between 5 to 9 million cubic yards will be mobilized and transported when they initiate the drawdown of the reservoirs.

“It’s a classic blow and go approach,” said Mr. Bransom. “We’re going to open it up and draw those big reservoirs down about 5 feet a day. We’ve been given a window from January 1st to the end of February in whatever the drawdown year is by the fisheries agencies and the tribes which is the most biologically dormant period of the year. We’re hopeful for high flows. We’re working with the Bureau of Reclamation and others in the event we need a little bit of augmentation flow from Upper Klamath Lake with the mobilization and transport, but our goal is to push that as much of that sediment out to the ocean in that 8 to 10 week period as we can. It’s primarily fine sediment, so we do anticipate that the sediment will relatively easily mobilize in the water column and be transported downriver.”

Then they will begin dam and hydropower removal. There will be over 8000 acres of lands that will be exposed when the reservoirs are drawn down, so there will be a massive lands and river restoration project to follow.

“We’ll get out on those lands, probably with initial aerial hydroseeding,” said Mr. Bransom. “As the sediments dewater, we’ll get out there with equipment for installation of temporary irrigation and seed planting. We currently have nursery-scale plant operations underway and we’re collecting tons of seed every year. We’ll be propagating thousands and thousands of container plants and trees, all with the goal of getting these 8000 acres planted as soon as we can after the drawdown and warm up.”

Then they will focus on river-based recreation. There is a lot of lake-based flat water recreation currently, so they will be replacing those facilities with fishing and boating access and some campgrounds. The focus will be primarily active river based recreation.

BENEFITS OF THE PROJECT

There are numerous benefits from the project. Dam removal and restoration will create access to up to 400 miles of mainstem and tributary habitat for Pacific lamprey, steelhead, coho and chinook runs. The project will create 400-500 direct jobs resulting from the construction and as many as 1000 or more indirect jobs. The salmon industry on the Klamath River historically the third largest salmon producing watershed on the entire West Coast, so they anticipate significant economic benefits for the fisheries, recreation, and tourism.

There are numerous benefits from the project. Dam removal and restoration will create access to up to 400 miles of mainstem and tributary habitat for Pacific lamprey, steelhead, coho and chinook runs. The project will create 400-500 direct jobs resulting from the construction and as many as 1000 or more indirect jobs. The salmon industry on the Klamath River historically the third largest salmon producing watershed on the entire West Coast, so they anticipate significant economic benefits for the fisheries, recreation, and tourism.

There also will be significant water quality benefits; there is often toxic blue-green algae  behind the reservoirs in the summer requiring public health warnings. Restoration will also help with the fish disease problems that have been a problem in dry years.

behind the reservoirs in the summer requiring public health warnings. Restoration will also help with the fish disease problems that have been a problem in dry years.

“The agricultural community particularly in the upper basin is beginning to come around on the benefits of dam removal,” said Mr. Bransom. “They lost the KBRA which had benefits for agriculture, but they now see that dam removal has the opportunity to provide some direct and indirect benefits. The biological opinion for the Klamath Irrigation Project requires the release of flushing flows to address fish disease every year. If we can alleviate that disease condition, there is the potential for regulatory relief that could leave as much as 50,000 acre-feet of additional water in Upper Klamath Lake that could be used for agricultural purposes.”

Senior Department of the Interior official Alan Mikkelsen is working to try to recreate some of the conditions that were considered under the original agreements, but he has been very clear that dam removal is a necessary first step to achieving those broader benefits in the Klamath Basin.

Senior Department of the Interior official Alan Mikkelsen is working to try to recreate some of the conditions that were considered under the original agreements, but he has been very clear that dam removal is a necessary first step to achieving those broader benefits in the Klamath Basin.

“We are thankful for the increasing support from the agricultural community as well as the support that we have from the tribes, which is obviously a major motivation for doing this project – to reconnect the social and cultural fabric of the tribes back to the river,” said Mr. Bransom.

REGULATORY PROCESSES

In 2016, the KRRC filed applications with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to transfer the hydroelectric license that PacifiCorp operates under to the KRRC. Subsequently, FERC will consider the surrender of the license back to FERC and the approval of a decommissioning plan. Even though those applications are to be considered sequentially, they are asking questions related to both.

In 2016, the KRRC filed applications with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to transfer the hydroelectric license that PacifiCorp operates under to the KRRC. Subsequently, FERC will consider the surrender of the license back to FERC and the approval of a decommissioning plan. Even though those applications are to be considered sequentially, they are asking questions related to both.

“I’m only interested in taking transfer of the license and the facilities with the assurance that I’m going to be able to meet the conditions of surrender order and implement a decommissioning plan,” Mr. Bransom said.

There are a number of critical questions to be addressed; they are working on an updated cost estimate as the Board of Consultants has pointed out some fundamental issues with the original cost estimate.

“FERC has asked us the very astute question, what if the project costs $450 million plus $1? Where will that money come from?,” said Mr. Bransom. “We’re working on the response to that question. We change the project scope; we go out and we raise more money. Those are basically the options that we have to address that question, so we’re putting together our thinking on the best potential response.”

They are working on consultations with the agencies regarding endangered species and a biological opinion will be prepared. They are also working on 401 and 404 certifications.

TRIBAL PARTICIPATION

The KRRC has been conducting formal tribal consultation as required under both state and federal statutes. Mr. Bransom said they take the obligation to the nine affected tribes very seriously as it is very significant for the historically salmon-dependent tribes, but he acknowledged that they do not enjoy universal support for the project among tribes.

“A number of those affected tribes had historic territory on lands that are now inundated, and they have significant cultural resources – burial grounds, fishing villages and other significant resources that they would just as soon see remain inundated by those reservoirs,” he said. “It’s a very interesting dilemma that we have and a very intricate process to ensure that we put in place the appropriate plans for the protection of those resources, both during drawdown of those reservoirs when we’re most likely to have an impact and then during the subsequent restoration.”

There is only an 8 to 10 week window to get the drawdown of the reservoirs done or they will lose an entire year, so if they impact a cultural resource, they have to have plans to address that so they can stay on schedule. He acknowledged the value of the cultural resources working group to resolve the significant issues.

RISK MANAGEMENT

As noted in the previous presentation, risk management and liability is also a challenge. “One of the most challenging provisions of the KHSA is that the dam removal entity is to provide indemnification for PacifiCorp and the states,” Mr. Bransom said. “We are literally stretching risk management and things that have been done in the insurance and liability transfer industry globally with things that have never been done. Part of what has taken us more time was to find an entity that is capable of assuming risk for things that nobody has ever been willing to assume risk for before.”

PacifiCorp has one vision of that and the KRRC has another, so they have to find a way to come together. “There are many questions, such as sediment,” he said. “What if we have an impact on the harbor at Crescent City and they have to do dredging? What if we have a failure? What if we impact properties around the reservoirs because of landslides? What if the revegetation isn’t successful? Who is going to be there after the KRRC sunsets 10-20 years down the road, not only to fulfill the mitigation obligations but to take on these risks and provide that indemnification? It’s a very challenging issue that we continue to work through. We’re blazing completely new ground here.”

PacifiCorp has one vision of that and the KRRC has another, so they have to find a way to come together. “There are many questions, such as sediment,” he said. “What if we have an impact on the harbor at Crescent City and they have to do dredging? What if we have a failure? What if we impact properties around the reservoirs because of landslides? What if the revegetation isn’t successful? Who is going to be there after the KRRC sunsets 10-20 years down the road, not only to fulfill the mitigation obligations but to take on these risks and provide that indemnification? It’s a very challenging issue that we continue to work through. We’re blazing completely new ground here.”

“I always like to end a presentation by saying the KRRC is honored to be implementing the KHSA and doing dam removal on behalf of tribes and other supporters, and we’re also honored to be working with folks who do not support the project,” he said. “I want to point out that the KRRC is simply building on the work of others that have come before us and we take that obligation and that commitment very seriously. Thank you very much.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION …

MATILIJA DAM REMOVAL

Peter Sheydayi is the Deputy Director for the Ventura County Watershed Protection District which was formed in 1944 as the Ventura County Flood Control District.

Peter Sheydayi is the Deputy Director for the Ventura County Watershed Protection District which was formed in 1944 as the Ventura County Flood Control District.

Unlike most of Southern California, Ventura County doesn’t have any imported water supplies; their water sources are Casitas Reservoir, surface water diversions, and groundwater. As opposed to probably most watersheds, the water supply agencies work pump groundwater first, so surface water is their backup supply and not their primary supply.

The Ventura River watershed encompasses 226 square miles. Average rainfall is 16” at the coast, 24” at the Matilija Dam, and about 40” up at the top of the watershed. Mr. Sheydayi noted that it is a very steep watershed with a lot of hydrologic differences throughout.

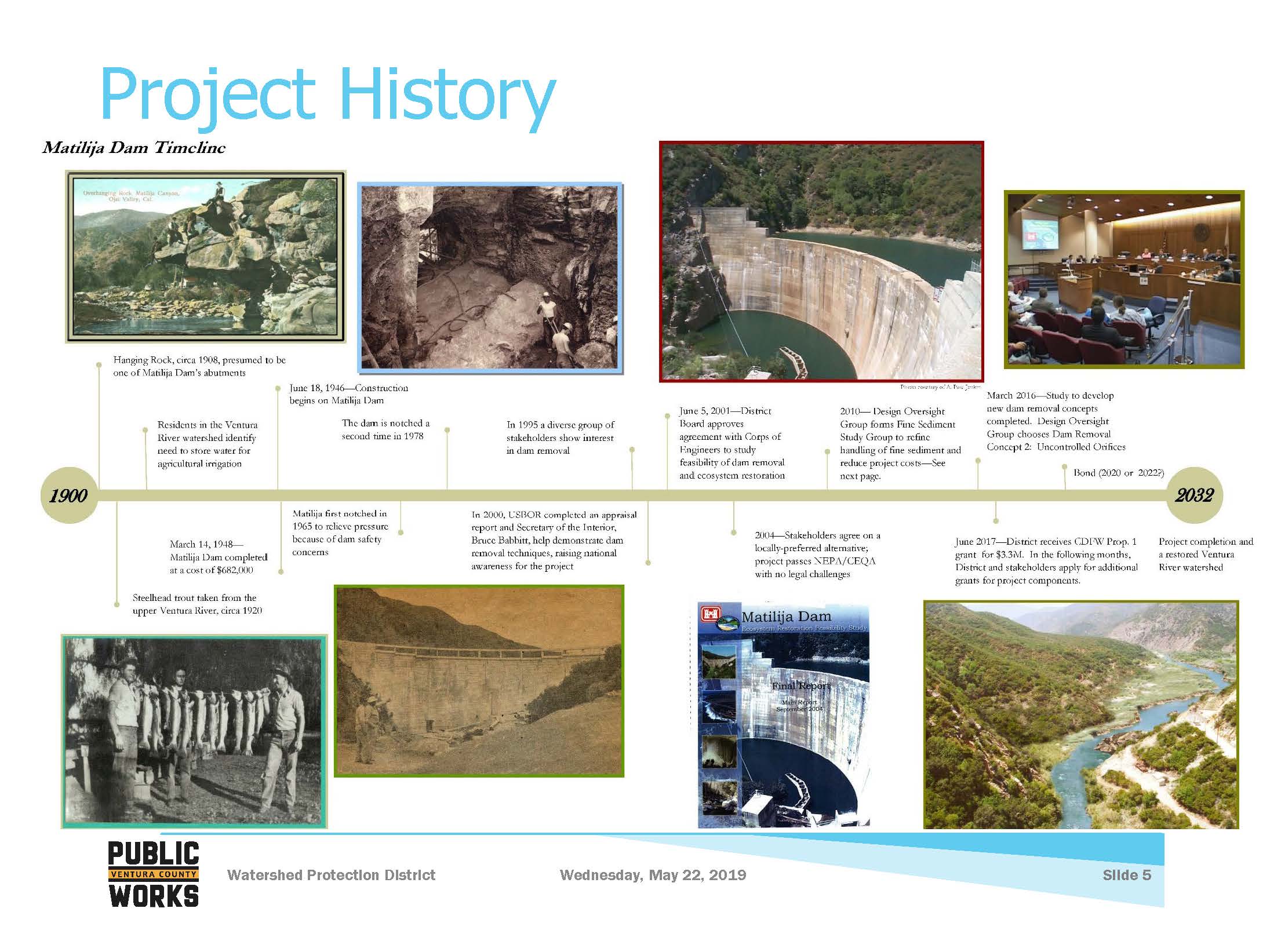

Prior to the construction of the dam, the Matilija Canyon was an actively used recreation area with a productive steelhead fishery. Construction began in 1946 and was completed in 1947; the reservoir began to fill up the next year.

Prior to the construction of the dam, the Matilija Canyon was an actively used recreation area with a productive steelhead fishery. Construction began in 1946 and was completed in 1947; the reservoir began to fill up the next year.

During the reservoir construction, it was determined that the concrete had alkali–silica reaction which is a condition where the sediment in the concrete is incompatible with cement which creates a process that weakens the concrete over time. However, this was discovered after the construction was too far along to do much about it, and so it was decided to try to manage within that condition.

The dam was originally 198 feet tall with a reservoir capacity of 700,000 acre-feet. In the 1960s the dam was notched, and in the 1970s it was notched a second time. Currently, there is about 8 million cubic yards of sediment behind the dam, and of the 700,000 acre-feet, only about 400 acre-feet is left.

“So there’s very little storage and no flood management that it was originally constructed for, so for all intents and purposes, the dam is obsolete,” Mr. Sheydayi said.

Folks started talking about removing the dam in the mid-1970s, but it wasn’t until the mid-1990s that a diverse group of stakeholders got serious and started lobbying the Board of Supervisors. The supervisors directed the then-Ventura County Flood Control District to look at removal alternatives, which was the beginning of the project.

In 2000, they requested that the US Bureau of Reclamation prepare a reconnaissance study report. They were visited by Bruce Babbitt, then the Secretary of the Interior, who helped highlight removal methods. It was then decided that the Corps of Engineers had authorizations that might be more compatible with dam removal, so in 2001, they entered into an agreement with the Corps to go through a feasibility process.

“We did keep the Bureau of Reclamation on the team; they were primary modelers for the sediment and hydraulic analysis done on the project, and in 2004 we completed a feasibility study as well as the CEQA and NEPA documents,” Mr. Sheydayi said.

“We did keep the Bureau of Reclamation on the team; they were primary modelers for the sediment and hydraulic analysis done on the project, and in 2004 we completed a feasibility study as well as the CEQA and NEPA documents,” Mr. Sheydayi said.

Eventually, they did get authorization in the Water Resources Development Act along with some design funding but no funding to begin construction. There were some hiccups in the planning which caused the cost of certain elements to increase substantially.

“Because of concerns with diversions to Casitas Reservoir, as part of the design, the Corps wanted to slurry all the fine sediment downstream of the diversion that Casitas uses,” said Mr. Sheydayi. “That process of slurring, which would have taken water and would have slurried through a pipeline downstream of the Ropas diversion and doubled the price, so the Corps began to look at new alternatives to handle fine sediment that consisted primarily of what would it look like if we stabilized sediment.”

The stakeholders were very much against the idea; they didn’t want to see the sediment stabilized or any permanent infrastructure constructed. In 2010, there was a fine sediment workgroup formed to look at different ideas. That was followed on by a grant from the Coastal Conservancy in which consultants were hired to look at new alternatives. In 2016, a new alternative was selected by consensus through the stakeholder process.

However, when the stakeholder groups selected their alternative for dealing with the sediment, it was understood that they were asking to District to back away from the Corps’ authorized project and the District didn’t have the funding to do what the stakeholders desired. So they are hoping to secure some bond funding.

“A number of the stakeholders, one in particular from NMFS said, if we pick the right alternative, the money will come, and so we began the process to develop a funding plan and move the project forward,” he said. “Our hope is that pending the securing of the funding, that the dam can come about by 2032, which still seems like a long way out, but there are a lot of elements to this ecosystem watershed project.”

The benefits of the project will be to improve aquatic and terrestrial habitat, restore natural processes of sediment moving down to the ocean to make the beaches more resilient, to enhance recreational opportunities, some of which have already been constructed, and to restore fish passage. The project would restore about 17 miles of rearing and over-summer habitat for steelhead.

The benefits of the project will be to improve aquatic and terrestrial habitat, restore natural processes of sediment moving down to the ocean to make the beaches more resilient, to enhance recreational opportunities, some of which have already been constructed, and to restore fish passage. The project would restore about 17 miles of rearing and over-summer habitat for steelhead.

“This is truly a watershed-wide project,” he said. “When you have a portion of the watershed locked up with sediment, it’s not only storing sediment but it is also trapping sediment, so that sediment no longer being trapped behind the dam will flow and contribute to the sediment that’s in the river and at the ocean, but a consequence of that also is because of changing conditions after dam removal, the river is expected in some locations to aggrade. That makes it a little challenging, because we have all this infrastructure – developed areas, transportation infrastructure, and water and sanitary infrastructure that was constructed with the dam in place. So all those entities know is a river with a dam upstream.”

As part of the project there will be two bridge replacements and levees to be built or modified. A large water supply improvement will be needed at the Robles Diversion which is a facility owned by Casitas Municipal Water District; that component is meant to be able to flush sediment that is coming to their diversion facility that would prohibit them from diverting water. And lastly, dam removal and the site restoration that will follow.

As part of the project there will be two bridge replacements and levees to be built or modified. A large water supply improvement will be needed at the Robles Diversion which is a facility owned by Casitas Municipal Water District; that component is meant to be able to flush sediment that is coming to their diversion facility that would prohibit them from diverting water. And lastly, dam removal and the site restoration that will follow.

The project is currently estimated to cost $150 million, which includes program management, legal and risk management, outreach and grant management, environmental compliance and engineering design. They currently have a CEQA and NEPA document and a biological opinion, which will have to be revisited with the new dam removal alternative selected.

He presented an idealistic schedule with construction occurring over a 15-year period.

He presented an idealistic schedule with construction occurring over a 15-year period.

The concept for removing the dam is to drill two 12-foot holes within the dam, leaving the upstream four feet of concrete in place. When a large event is forecasted for the watershed, they will charge the holes, and then as the storm approaches, those charged holes will then be blown and the sediment will evacuate through the dam.

“That has to have approval from the Division of Safety of Dams (DSOD), and they are a little concerned about the idea of blasting a dam that they have regulatory oversight over,” Mr. Sheydayi said.

They are also considering installing gates in the face of the dam as a contingency plan.

Currently, they are considering how predictable storms are. “If we look out 72 hours or more at a storm, how reliable are our weather forecasters that we’re going to get the storm that they forecasted we were going to get,” he said. “So some of what may go into the decision on whether to put gates are not, regardless of DSOD, may be a reflection of the outcome of that study to decide that if we really can’t rely on something with a long enough duration window that we can go in and charge those holes, then we really have to put gates on so that we can make a decision a little closer to the actual storm event.”

The other two projects highlighted by the previous speakers have a lot of stakeholders, and this project is no exception. “This is certainly a new process for watershed protection and the number of stakeholders that are involved in the project is tremendous; their involvement and support have been key to moving the project forward,” he said.

They have had some folks ask why they don’t strengthen the dam and remove the sediment, and then maintain the water resource it was constructed for. Mr. Sheydayi noted that there are a couple of problems. “One is that the funders and stakeholders that we have in place are interested in dam removal, and they would essentially cut away from the project if we weren’t talking about dam removal. And there’s 8 million cubic yards of sediment behind the dam. The community has made it very clear; they have no interest in seeing that amount of material trucked out of the watershed past their schools and homes and public spaces. Then also we have DSOD who is concerned about the strength of the dam, so we’re really moving forward with this stakeholder group looking at dam removal.”

They have been looking at project governance and project funding. There was funding for the project in Prop 3 which voters did not pass, so they have been discussing how the project will be funded moving forward. The Ventura River watershed is resource rich but cash poor, and that’s very true, he said.

They have been looking at project governance and project funding. There was funding for the project in Prop 3 which voters did not pass, so they have been discussing how the project will be funded moving forward. The Ventura River watershed is resource rich but cash poor, and that’s very true, he said.

“When the dam was built, there was an allowance in our District Act to raise money for dam removal post sediment filling up the dam,” he said. “In the act that they had an approval process that consisted of the board approval and an election, but now with Prop 218 and looking at having to meet those requirements, in order to raise local funding, it will be a difficult lift on the order of $150 million. It would be nearly impossible, so we are heavily reliant on looking at state, federal, and private grants.”

Most competitive grants have a 36-month window of completion, so with a project of this magnitude, won’t be able to use those types of grants. They have come to the realization that a significant portion of the funding needs to be from a bond, so they can set aside funds for future adaptive management, risk management and liability, as well as enough to give other potential funders that dam removal can be completed.

“Nobody really wants to put their money down first,” he said. “Everybody wants to be the last piece of the puzzle, and so a bond really needs to be significant issue in that regard.”

TAKEAWAYS …

Mr. Sheydayi then gave his take home comments.

The more development and infrastructure downstream, the more complex the project. “Where the Klamath doesn’t have a lot of development and water supply issues that we have, we have a lot of project components,” he said. “The majority of the cost is not on the dam removal and site restoration; the majority of the project is in downstream project components.”

State and federal funding is ‘a square peg in a round hole.’ “If I’m CDFW and a District applies for a grant to build a levee, I’m going to have an issue with that, and yet, these levees have to be constructed in order to remove the dam,” he said. “They want the dam removed but they don’t want to fund levees. Then have an agency like FEMA whose got a HMGP or some other PDM grant program and they’ll fund levees, but then when you tell them you need to build a levee because you’re going to remove a dam, they say, you’re creating your own problem. So the traditional infrastructure funders aren’t really interested in funding our stuff because we’re causing the risk and the resource agency funders that want to see dam removal are more willing to fund the dam removal itself, but less wanting to fund infrastructure. So that’s the conundrum we’re dealing with.”

Stakeholder involvement is key to the project’s success. “Without having a stakeholder consensus on the alternative we have, there’s no way that we would be able to move forward and be where we are. We’re currently working under at $3.3 million CFDW grant and that will take us all the way through updating CEQA and NEPA as well as intermediate plans for all of the project and its components. And we are currently looking for final design funding which will follow after that.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION …

- Click here for the Matilija Dam Ecosystem Restoration Project website.

- Click here for the Matilija Dam Coalition website.

DISCUSSION HIGHLIGHTS

Question to Jeff Syztel (San Clemente Dam): In your risk assessment, what were the most significant components of that risk that funneled towards the final decision to remove rather than upgrade or replace?

“The key issue there was whether or not a buttressed facility could be permitted,” said Mr. Syztel. “The National Marine Fisheries indicated that if Cal Am elected to pursue a buttressing option, they would issue a jeopardy opinion and therefore force Cal Am to pursue a more environmentally friendly option which would lead them to dam removal. So permitability – both in terms of implementation of the project and also long-term operation because they would still need to deal with the sediment, they still need to manage the fish passage concerns. It would address the stability but it wouldn’t address the host of other issues that the dam presented, so really it came down to compliance and permitting was the risk that pushed the entire group towards removal as opposed to buttressing.”

Question: You mentioned 35 dams had been taken away since 1970. Out of those 35, what do the studies show? What have been the effects?

Moderator David Manning with Sonoma County Water Agency said that the panelists probably couldn’t answer, but it’s about the improvements to fisheries. “Jeff, you’ve seen some immediate results. I think it’s very understood about the value of habitats upstream above the Klamath Dams, and the perturbations to habitat and water quality downstream, so those are two pretty clear cases. Elwha has been a success story, so of the major dam removal projects with fisheries as the intent, I think the consensus that I’ve seen reported is that they have a tremendous benefit for the ecosystem. Fish numbers increase, water quality improves, and habitats that were previously inaccessible are providing a high quality benefit to fish.”

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!