Minimum thresholds, measurable objectives, undesirable results: A panel of consultants discuss the specifics of how their GSAs determined sustainable management criteria

Minimum thresholds, measurable objectives, undesirable results: A panel of consultants discuss the specifics of how their GSAs determined sustainable management criteria

The passage of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act in 2014 requires that groundwater basins be managed such that the use of groundwater can be maintained during the planning and implementation horizon without causing undesirable results. In order to demonstrate sustainability, the Groundwater Sustainability Plan regulations require the development of locally-defined quantitative sustainable management criteria, including undesirable results, minimum thresholds, and measurable objectives.

At the second annual Groundwater Sustainability Agency Summit, hosted by the Groundwater Resources Association in June of this year, a panel of consultants discussed the process and the specifics of how they developed sustainable management criteria for their basins.

SUSTAINABLE MANAGEMENT CRITERIA: INTRODUCTION

First, Moderator Amanda Peisch-Derby from the Department of Water Resources gave a brief overview of the definitions, as the regulations have very specific information that a GSA has to include in a Groundwater Sustainability Plan:

The sustainability goal is a component of the Groundwater Sustainability Plan (GSP) that describes the mission or objective of the objective of the entire basin, how the conditions of the groundwater are going to be managed, and what measures the GSA will take to bring the basin into sustainability within the 20-year planning and implementation period.

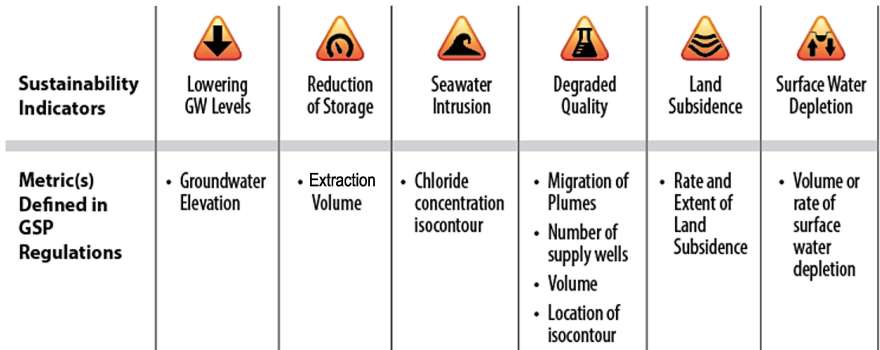

The sustainability indicators are the effects caused by groundwater conditions that are occurring within a basin that, when significant and unreasonable, become undesirable results. SGMA defines six undesirable results: chronic lowering of groundwater levels, reduction of groundwater storage, seawater intrusion, land subsidence, water quality degradation, and depletions of interconnected surface water.

“The significant and unreasonable occurrence of any of these six sustainability indicators constitutes an undesirable result,” said Ms. Peisch-Derby. “But not all six of these indicators will apply to a particular basin, so it’s up to the GSA to provide enough evidence that the indicator does not occur or would not occur in the future within their groundwater sustainability plan, and the Department is going to evaluate that.”

In preparing their GSPs, GSAs are going to have to consider the condition of each of the six sustainability indicators and quantify at what point they become significant and unreasonable in that basin, she explained. She also noted that when defining what an undesirable result is, a GSA must consider all beneficial uses and users of groundwater, as well as land use and property interests in the basin.

Measurable objectives are the specific, quantifiable goals for the maintenance or improvement of groundwater conditions that have been included in an adopted Plan.

Measurable objectives are the specific, quantifiable goals for the maintenance or improvement of groundwater conditions that have been included in an adopted Plan.

The minimum threshold is the quantitative value that represents the groundwater condition in each representative monitoring well site that when exceeded, may cause an undesirable result.

Interim milestones are set every 5 years as a benchmark to achieve with each update. These milestones might change as things progress and data gaps are filled.

The area between measurable objective and minimum threshold is the zone of operational flexibility.

The regulations define very specific metrics that are set for each sustainability indicator in order to provide consistency within the groundwater basin as well as for adjacent basins. A GSA may use groundwater elevations as a proxy, but there needs to be significant correlation between groundwater elevation and the sustainability indicator.

The regulations define very specific metrics that are set for each sustainability indicator in order to provide consistency within the groundwater basin as well as for adjacent basins. A GSA may use groundwater elevations as a proxy, but there needs to be significant correlation between groundwater elevation and the sustainability indicator.

Ms. Peisch-Derby reminded that the sustainable management criteria are locally defined, and while the panel will be discussing real word examples, they can be very specific to local conditions and therefore may not be directly applicable to another basin.

“All these items are under development, none of these items are final, and not even the Department has validated these or approved them,” she said as a caveat to the coming discussion. “The Department has provided the best management practices for development of sustainable management criteria, which is available on our website.”

THE PANEL PARTICIPANTS

Seated on the panel:

Georgina King is a hydrogeologist at Montgomery & Associates based in Oakland, CA. She was educated in South Africa and spent her early career working for the South African government before working in water resources in California. She is currently working on the development of two groundwater sustainability plans on the Central Coast.

Trey Driscoll is the principal hydrogeologist for Dudek based in San Diego. He is a consulting project manager for the Borrego Valley Groundwater Sustainability Agency and has been working in the Borrego Valley basin for the past six years.

Ronnie Samuelian is the principal engineer with Provost & Pritchard consulting group in Fresno. He is the plan manager in the Kings Subbasin, responsible for facilitation and coordination of seven GSAs preparing seven GSPs.

Each panelist then gave a brief presentation, discussing one or two of the sustainability indicators that have been developed in their basin.

GEORGINA KING: Seawater intrusion and interconnected surface water depletions

Georgina King discussed her work in the Santa Cruz Mid County Basin, which is rather small in comparison to some of the basins other panelists have.

The basin has one GSA and is developing one GSP; they have no management areas. The map on the slide shows the basin boundary. It is considered a high priority basin because of seawater intrusion, and the bigger dots on the map depict where the chloride is higher, indicating seawater intrusion. Five of the sustainability indicators are applicable in this basin and land subsidence is not, because the geology is not susceptible to subsidence, she said.

The basin has one GSA and is developing one GSP; they have no management areas. The map on the slide shows the basin boundary. It is considered a high priority basin because of seawater intrusion, and the bigger dots on the map depict where the chloride is higher, indicating seawater intrusion. Five of the sustainability indicators are applicable in this basin and land subsidence is not, because the geology is not susceptible to subsidence, she said.

Ms. King’s presentation discussed the development of criteria for seawater intrusion and for surface water depletion.

In the Santa Cruz Mid-County Basin, the board set up an advisory committee comprised of representatives of beneficial users and uses in the groundwater basin. There are some technical people on the advisory committee, but the majority of them are not technical. While this has presented its own challenges, the outcome has been very good, she said.

The diagram depicts their process for development of the criteria. She emphasized that it was an iterative process, and that they had to understand the basin and work through it numerous times. As part of the process, they gave the committee at least two classes on each indicator, making sure everyone was clear on what works in that basin, what is sustainable and what’s not sustainable.

The diagram depicts their process for development of the criteria. She emphasized that it was an iterative process, and that they had to understand the basin and work through it numerous times. As part of the process, they gave the committee at least two classes on each indicator, making sure everyone was clear on what works in that basin, what is sustainable and what’s not sustainable.

“If you have people having different ideas of whether we have a problem with surface water depletion or we don’t, you have to get that all sorted out before you can progress on to the next step,” Ms. King advised.

They then provided a proposal to the advisory committee and said, ‘this is significant and unreasonable; tell us what you think significant and unreasonable conditions in your basin and what do you want to avoid.’ From that, they developed the specific quantifiable criteria for the minimum threshold, which is the metric or specific value that the indicator shouldn’t fall below. The measurable objectives came a little bit later, she said.

“If you have the luxury of time, then many can do it this way and it worked out well for us,” she said.

She noted that they are still fine tuning these indicators, so what she showed during the panel session may be a bit different than what ends up in the final plan.

Seawater intrusion

Ms. King then discussed how they set the criteria for seawater intrusion. After a few iterations with the advisory committee, they decided that significant and unreasonable would be if seawater moves farther inland than it had been over the past five years. From that, they had to develop an indicator for the undesirable result that reflected that.

The undesirable result is defined as chloride increases in wells either side of the isocontour; this basin has been managed successfully for a few decades using predictive groundwater elevations, so they are also using groundwater elevations as a proxy as well.

“We don’t have just one, we have two, and if the undesirable result happens in any one of those, it’s undesirable,” said Ms. King. “It’s not like both have to record before its undesirable.”

The minimum thresholds the tie back to the undesirable results which they decided to set at 250 milligrams per liter; protective elevations are set to protect the bottom of the production wells that are close to the coast. The measurable objective is a lower concentration of chloride in the basin with most concentrations in the basin less than 100 milligrams per liter of chloride. Protective elevations are increased so that the entire depth of the aquifer is protected, even if the well is not screened down to that depth.

Interconnected surface water depletion

The depletion of interconnected surface water is much less understood. Of all the indicators, it’s probably the hardest one, Ms. King said. There definitely is a connection between surface water and groundwater in the basin. They had to have a working group to help, which included NOAA Fisheries.

The depletion of interconnected surface water is much less understood. Of all the indicators, it’s probably the hardest one, Ms. King said. There definitely is a connection between surface water and groundwater in the basin. They had to have a working group to help, which included NOAA Fisheries.

“It’s depletion that has to be just due to groundwater extraction,” she said. “There are many other things that affect stream water depletion: evapotranspiration, how much fog there is, and others, so it has to be related to groundwater extraction in streams that support priority species greater than that that has occurred over the period of record of 10 years.”

Ms. King said they do have some shallow wells and wells next to creeks, so there is some existing data.

The undesirable result is any shallow representative monitoring well’s groundwater elevation falling below its minimum threshold; they are using groundwater elevations as a proxy as there is a volume of surface water depletion that corresponds with it and so they have to provide evidence linking the groundwater levels to surface water depletion. The minimum threshold is the highest seasonal-low groundwater elevation in representative monitoring wells during below-average rainfall years.

The measurable objective, ‘exceeds the minimum threshold by the range in seasonal-low shallow elevations over the period of record,’ provides for more operational flexibility when the groundwater level is a bit higher. She acknowledged that there are data gaps with this indicator so these might change over the next 20 years as they further understand the interconnection of them.

Sustainability goal

To develop the basin’s sustainability goal, they discussed it with the advisory committee right at the beginning of the process who came up with their sustainability goal for the basin. After they had been working on the sustainability management criteria for over a year, they then revisited the sustainability goal and edited it to more strongly reflect the sustainability management criteria.

To develop the basin’s sustainability goal, they discussed it with the advisory committee right at the beginning of the process who came up with their sustainability goal for the basin. After they had been working on the sustainability management criteria for over a year, they then revisited the sustainability goal and edited it to more strongly reflect the sustainability management criteria.

“I don’t think it was the case where the goal drove the sustainability management criteria, I think it’s more iterative than that,” said Ms. King.

TREY DRISCOLL: Chronic lowering of groundwater levels and reduction in groundwater storage

Trey Driscoll is working in the Borrego Springs subbasin; the subbasin covers 60,000 acres and is surrounded by the Anza Borrego Desert State Park, the largest state park in California. They completed a basin boundary modification in 2016 that was based on both scientific and jurisdictional boundaries, which created the new Borrego Springs subbasin which is the critically overdrafted portion of the basin and where all pumping occurs.

Trey Driscoll is working in the Borrego Springs subbasin; the subbasin covers 60,000 acres and is surrounded by the Anza Borrego Desert State Park, the largest state park in California. They completed a basin boundary modification in 2016 that was based on both scientific and jurisdictional boundaries, which created the new Borrego Springs subbasin which is the critically overdrafted portion of the basin and where all pumping occurs.

The agency is comprised of the Borrego Water District and San Diego County. The GSA has developed a draft GSP that has been released for public comment; they are currently in the process of responding to public comments that have been received.

Since they are a critically-overdrafted basin, chronic lowering of groundwater levels and reduction of groundwater storage their paramount concerns.

The basin is divided the basin into three management areas, based on several factors including the overlying land use and where pumping occurs; there’s also a barrier that restricts groundwater flow between the central and south management area.

Mr. Driscoll presented a graph showing groundwater levels from 1953 to 2018 showing a decline of 125 feet over the period of 64 years. The graph is just showing the North Management Area where most of the pumping occurs. In the Central Management Area, groundwater levels have declined about 85 feet, and in the South Management Area because of the groundwater barrier, it’s much less and in some areas, not much decline at all, he said.

First step: hydrogeologic conceptual model and water budget

To develop the sustainable management criteria, they started with the hydrogeologic conceptual model and the water budget. In the northern part of the basin, the majority of the outflow from the basin is from ag water pumping, to a lesser extent there is pumping for golf courses and municipal use in the central and the southern management area.

To develop the sustainable management criteria, they started with the hydrogeologic conceptual model and the water budget. In the northern part of the basin, the majority of the outflow from the basin is from ag water pumping, to a lesser extent there is pumping for golf courses and municipal use in the central and the southern management area.

“This is a great visual tool to show where there are inflows and outflows occurring in basins,” Mr. Driscoll said.

The water budget for the period of 2005 through 2015 shows that outflows were approximately 20,000 acre-feet and the inflows were approximately 5,000 acre-feet.

“We’re 100% groundwater dependent,” he said. “We’ve looked at the option of imported water but it isn’t economically feasible at this time, so in summary, we’re looking at draconian 74% reduction in pumping over the 20 year implementation period.”

Reduction in groundwater levels

For the criteria for reduction in groundwater levels, the sustainability goal is for water levels stabilize or improve and to maintain groundwater above minimum threshold. The undesirable result is that water levels drop to levels no longer able to support groundwater production wells and the overlying beneficial uses. The measurable objective is to maintain water levels within the modeled levels. The minimum threshold is to maintain groundwater above saturated screen intervals in key municipal wells to be used throughout the planning horizon.

For the criteria for reduction in groundwater levels, the sustainability goal is for water levels stabilize or improve and to maintain groundwater above minimum threshold. The undesirable result is that water levels drop to levels no longer able to support groundwater production wells and the overlying beneficial uses. The measurable objective is to maintain water levels within the modeled levels. The minimum threshold is to maintain groundwater above saturated screen intervals in key municipal wells to be used throughout the planning horizon.

“Some have suggested that this doesn’t take into account all beneficial users, but I should state that if these municipal wells are protected, most of the wells that produce water by ag are also protected,” he said. “We also have a few, about 50 or so plus de minimus users in the basin. It is technically and financially feasible to not only connect those to the district system which would be the municipal wells, or there’s also the possibility to drill new wells for them.”

The graph depicts an example of a district well in the basin. The basin is divided into three aquifers; however, those aquifers aren’t uniformly distributed across the basin.

The graph depicts an example of a district well in the basin. The basin is divided into three aquifers; however, those aquifers aren’t uniformly distributed across the basin.

“We initially played around with looking at preserving water in the upper aquifer as one of our goals, however, there are portions of the basins, because of undulations of these aquifers where the upper aquifers aren’t even saturated,” he said.

The chart shows the historical decline in groundwater levels based on numeric model and as well as future projections; for climate change, they used the DWR change factors in the model.

“In this basin, we can see that with the municipal well, the saturated portions of the screen are preserved over time,” Mr. Driscoll said. He noted that the projections are based on a linear ramp down of about 18.5% every 5 years.

Reduction in groundwater storage

He presented a chart showing the cumulative change in groundwater storage for the period of 1945 through 2016, noting that during that time, approximately 520,000 acre-feet of groundwater has been removed from groundwater storage.

He presented a chart showing the cumulative change in groundwater storage for the period of 1945 through 2016, noting that during that time, approximately 520,000 acre-feet of groundwater has been removed from groundwater storage.

For the criteria for groundwater storage, the sustainability goal is to have long-term use less than or equal to the initial sustainable yield of 5700 acre-feet per year. Mr. Driscoll noted that this is a planning level estimate; they expect that during the 5 year updates, new data will be collected and this level is likely to change over time.

The undesirable result would be a reduction in storage is at a level that is no longer able to support municipal production wells. The measurable objective through 2040 is to allow no more than 72,000 acre-feet of additional reduction in storage. The minimum threshold is to allow no more than 145,000 acre-feet of additional reduction in storage.

The chart (lower, left) shows the historical cumulative reduction in storage, as well as the measurable objective and the minimum threshold. “Our measurable objective isn’t really a straight line on the bottom, and that’s because we expect there to be adaptive management and that value could change over time as we collect additional information,” Mr. Driscoll said.

The chart (above, right) shows how they developed the minimum threshold for reduction of groundwater storage. It’s a Monte Carlo simulation that looks at the historical data that came out of the numeric model.

“What this really shows that there’s extreme variability in recharge in these desert basins,” he said. “It may be symptomatic of what you see in other basins in California which is that you’re going to have drier dry periods and deserts area already fairly dry, but you’re also going to have wetter wet periods. In many years in these desert basins, you get very, very little recharge. Most of the recharge is coming from these large episodic events.”

Minimum thresholds and monitoring

They used the 20th percentile to develop minimum thresholds. “Instead of using an average, we wanted to be a little bit more conservative, so using the historical climate data, 80% of the time in the next 20 years during our implementation period it’s going to be wetter and 20% of the time, it’s going to be drier. We didn’t use every single year in this simulation; we were actually looking at 53 20-year periods because when you look at the climate data for this basin might not apply to others, as we see strong decadal wet and dry periods.”

Mr. Driscoll emphasized that their plan is heavy on monitoring. “You really can’t implement SGMA without monitoring,” he said. “The map shows our extensive monitoring network. DWR is actually monitoring more wells than we even have on this map. Currently, we’re sampling over 30 wells for groundwater quality. Currently all the municipal and golf courses are monitoring production as that is a big data gap in our model. Part of the plan we would have mandated metering of all wells in the basin.”

Mr. Driscoll emphasized that their plan is heavy on monitoring. “You really can’t implement SGMA without monitoring,” he said. “The map shows our extensive monitoring network. DWR is actually monitoring more wells than we even have on this map. Currently, we’re sampling over 30 wells for groundwater quality. Currently all the municipal and golf courses are monitoring production as that is a big data gap in our model. Part of the plan we would have mandated metering of all wells in the basin.”

RONNIE SAMUELIAN:

Ronnie Samuelian is with Provost and Pritchard and is working in the Kings subbasin where they have seven GSAs developing seven GSPs. They have a coordination committee of representatives from each of the GSAs that have been meeting since 2016. They are using a common outline for all of the GSPs that are being developed.

Ronnie Samuelian is with Provost and Pritchard and is working in the Kings subbasin where they have seven GSAs developing seven GSPs. They have a coordination committee of representatives from each of the GSAs that have been meeting since 2016. They are using a common outline for all of the GSPs that are being developed.

“It’s really not unlike that I’ve heard many of the basins that have multiple GSAs are doing one GSP with chapters for the individual entities,” he said. “The difference between us is when you turn to section 4.5.2.1 Groundwater storage minimum thresholds, you can look at all seven plans and it reads all the same. That’s our goal, but until the coordination agreement is done, they’re not all submitted.”

The Kings subbasin covers almost a million acres. There is roughly 1.2 MAF surface water on average that is brought into the basin; Mr. Samuelian noted that surface supplies vary significantly.

The North Kings GSA, the Central Kings GSA, and the Kings River East have 1.5 to 2 acre-feet per acre of surface water; their water rights are very secure, having been established in the 1800s. The McMullin Area GSA doesn’t have any surface water, and is almost entirely planted over to permanent crop.

There’s about 120,000 AF overdraft over the million acres, which comparatively with other areas of the Central Valley is not actually that bad, probably because of the surface water rights that are held, he said.

They used a base period of water years 1997 through 2011 which included some of the recent changes in cropping patterns and provided the historical average amount of surface water brought into the basin.

“In our basin, surface water dictates how much groundwater we pump, and those surface water rights are tied to runoff, but certain amounts in dry years will come in for the priority water right holders and go to other areas outside of the subbasin, so that was a critical factor in evaluating what base period we should use,” Mr. Samuelian said.

Land use in the basin is about 80% agricultural land, and planted with mostly permanent crops. There are numerous cities and communities, including Fresno, the fifth largest in the state. There are close to 40 different water purveyors or providers in the basin.

Land use in the basin is about 80% agricultural land, and planted with mostly permanent crops. There are numerous cities and communities, including Fresno, the fifth largest in the state. There are close to 40 different water purveyors or providers in the basin.

The San Joaquin borders the basin on the north; the Kings River provides about 92% of the overall surface supplies in the subbasin. There is an area of Corcoran clay that starts roughly between the north Kings and McMullin boundaries and between the North Fork and Central Kings boundaries; that provides a confined aquifer. These create considerable differences across the GSAs which has been interesting to discuss as a group, Mr. Samuelian said.

Addressing groundwater declines

The sustainable management criteria of concern are primarily groundwater levels. The basin doesn’t have seawater intrusion and land subsidence is limited as there are only suitable geologic materials for land subsidence on the western edge of their basin which they think is being largely impacted by pumping from neighboring basins. They have a little bit of interconnected groundwater-surface water primarily on the eastern edge that they don’t think is causing any concerns but they continue to monitor it.

Coordination has been challenging, as everyone started at different times. Some GSAs had funding and some had to get funding, so a few of the GSAs are farther along in their development than others. Those that were already developing their plans brought their minimum thresholds and measurable objectives to the coordinating group, who would then take that back to their individual GSA’s technical committees, review it, and bring back any changes they would want to the coordinating group; that process continues.

Coordination has been challenging, as everyone started at different times. Some GSAs had funding and some had to get funding, so a few of the GSAs are farther along in their development than others. Those that were already developing their plans brought their minimum thresholds and measurable objectives to the coordinating group, who would then take that back to their individual GSA’s technical committees, review it, and bring back any changes they would want to the coordinating group; that process continues.

Their draft sustainability goal is pretty high level qualitative statement: “to ensure the basin is being operated to maintain a reliable water supply for current and future beneficial uses without experiencing undesirable results”. Conditions are sustainable when the basin continuously operated within its sustainable yield, the decline of the groundwater table is corrected, the multi-year trend of water elevations in these wells has been stabilized, and groundwater levels are maintained to prevent undesirable results of the applicable sustainability indicators.

Groundwater has been monitored in the area from before the dams were built and interestingly, it was used to justify some of the dams. The blue dots on the map are the monitoring wells with historical data that have been monitored in the basin. They have roughly 900 wells that are actively receiving seasonal data collection; they have about 140 indicator wells that have measurable objectives and minimum thresholds set.

Groundwater has been monitored in the area from before the dams were built and interestingly, it was used to justify some of the dams. The blue dots on the map are the monitoring wells with historical data that have been monitored in the basin. They have roughly 900 wells that are actively receiving seasonal data collection; they have about 140 indicator wells that have measurable objectives and minimum thresholds set.

There’s more than 20,000 wells in the basin. A lot of the area on the east side has been carved into parcels and even though they have surface water, they also have a groundwater well.

“Unlike DWR’s graphs that have show water levels rebounding, we’re going to land the plane but we’re going to see continued decline until we get there,” Mr. Samuelian said. “We have used the historic decline of our indicator wells to set where we were going to go if nothing happened, and then we’ve included a rate of mitigation for correction, and the basin right now is targeting an incremental correction of 10% in the first five years, an additional 20 in the next 5 and so forth, to get to that total corrected amounted.”

“Unlike DWR’s graphs that have show water levels rebounding, we’re going to land the plane but we’re going to see continued decline until we get there,” Mr. Samuelian said. “We have used the historic decline of our indicator wells to set where we were going to go if nothing happened, and then we’ve included a rate of mitigation for correction, and the basin right now is targeting an incremental correction of 10% in the first five years, an additional 20 in the next 5 and so forth, to get to that total corrected amounted.”

He noted that there’s a lot of uncertainty, so things could change over the first five years. “Nobody knows what the hydrologic conditions will be, but we know we’ll have funding that will need to be developed and generated,” he said. “Projects just don’t happen overnight, so it will take awhile before those actions take place.”

Mr. Samuelian noted that it’s the measurable objective that controls in the basin. “The base of usable water in the aquifer is very deep. This is a big aquifer, so as these GSPs are rolled out, many stakeholders are saying, why not just keep pumping? It’s a big aquifer. What causes an undesirable result? If it dropped it down so far that you couldn’t actually drill a well, or the water was of such poor quality that you couldn’t treat for it. That’s well below where we’re ever going to go, so the measurable objective of reaching sustainability by 2040 becomes the control, and minimum threshold .. is based on how much we need to operate during the period. We’ve chosen to use roughly the period that the worst drought we’ve seen in just about ever … 2012-2016. We looked at the decline and what was really occurring in the area and that’s the operational flexibility that we’d like to maintain to set our minimum thresholds.”

PANEL DISCUSSION

Moderator Amanda Peisch-Derby then asked the panelists a series of questions. If minimum thresholds are exceeded and undesirable results occur, has the GSAs determined how this will be addressed through the 20 year planning horizon?

Trey Driscoll (Borrego Springs): “At least for groundwater storage and groundwater levels that the minimum threshold is such that we would not exceed it in the first five or ten or even fifteen year period. We’re fully expecting an adaptive plan. We do have data gaps, where we do not have production or meter data for a majority of wells in the basin that represent the largest groundwater withdrawal. So over time, we will have refined our numeric models, we’ll be able to refine our interim models; those are really the five year checks to see if you’re on track to meet your measurable objectives, so if you are exceeding your interim milestone, you need to explain why. That could be that we’re in another historic drought or that there’s something in the data or your understanding of the basin has changed, but in some ways, I think the intent of implementation is to be adaptive.”

Ronnie Samuelian (Kings Basin): “Yes, they are in the plan and the program. A lot of areas, particularly the water rich areas, will focus on demand management strategies that they probably hope they don’t have to implement otherwise. Clearly in the areas without water supply are going to have some of that as part of their initial plan, but we are setting it low. Let me just add .. if one well exceeds an MT, then we’re going to take action. To me, that’s fascinating because a lot of the discussion is on is it multiple wells or some percentage of wells? …. At least in my view, if one indicator well is exceeded, that causes action needed for that area, whether that’s investigation or further, but one well is representing a large area and it seems like you need to do something about it, and not just say, well, that’s one is fine, but we need to get three or more. We haven’t finished if we don’t all agree on that in the GSA.”

Georgina King (Santa Cruz Mid County Basin): “For seawater intrusion, groundwater levels at the coast in the next 20 years, may be below minimum threshold still, but we’ve fine tuned our pumping distribution and we’re really hoping the projects that we have planned will actually happen. Adaptive management, thank goodness we have that because we can’t tell for sure right now what’s going to happen over the next five or even two years. We acknowledge that there are minimum thresholds that are exceeded but by 2040 we’re confident that we have levels above that, high enough to protect the basin from seawater intrusion. In Santa Cruz, people are fairly conservative. They really want to protect to the highest level possible, so we’ve had to demonstrate through modeling that the projects and the actions we’re going to take are going to get groundwater levels up to the level to protect against seawater intrusion.”

Question: There was a mention of groundwater elevations as a proxy, so how you’re going to demonstrate that there is a significant correlation?

Georgina King (Santa Cruz Mid County Basin): “For seawater intrusion, we’re using a proxy that’s pretty simple to demonstrate because groundwater levels below seawater will definitely induce seawater intrusion. Surface water depletion is more difficult because we can’t actually measure the depletion of surface water flow when a production well goes on. We’ve been monitoring that for several years … We do know that over the long term, there’s a diffuse interaction, and that when they reduce pumping in the deep aquifer and those levels increase, the shallow levels increase as well, so that one is more difficult. We’re using groundwater modeling to try and demonstrate that connection.”

Trey Driscoll (Borrego): “There’s definitely indirect and direct relationships of groundwater levels with several of the sustainability indicators. Obviously, for groundwater in storage, there’s a definite relationship of groundwater levels, so in our basin, it’s pretty easy to use groundwater levels as a proxy for groundwater storage. We do have a portion of the basin where we have some naturally occurring constituents, primarily arsenic, that are a little bit elevated and we had several of the stakeholders ask us, can you project what’s going to happen if groundwater levels decline, what’s going to happen to the water quality, and at this time, we don’t have sufficient data to come up with a groundwater threshold that was going to be protective of water quality, so that’s just one example that we have to deal with.”

Question: How did you ensure that beneficial uses and users of groundwater were considered in the development of the sustainable management criteria?

Ronnie Samuelian (Kings Basin) acknowledged the challenge. “The Kings Basin GSAs actually just sponsored a televised groundwater forum on our local Fox 26 station. The challenge of what we all are interested in and know is critical to our society and how the public views it is was played out in full display on that TV, because every time they panned the audience to the person who was moderating, there was person in the front row right behind him who was knitting with her head down the whole time. How do you get that person to look up and be interested because we know it matters, and that’s the challenge.”

“For the North Fork Kings GSA, it’s been a pretty exhaustive list of workshops and outreach and engagement, and sessions with 5 or 20 people showing up to over 200 people coming,” Mr. Samuelian continued. “The primary driver has been in most of them, a representative stakeholder group serving as the technical advisory committee, and that committee is really the primary representative driving the development of the plan as they roll it out and get further feedback. Those technical advisory committees have been varied group of stakeholders.”

Trey Driscoll (Borrego Springs): “In the Borrego Springs subbasin, we had an advisory committee process and we held over 20 stakeholder meetings. The advisory committee was comprised of the different beneficial users in the basin. We’ve now released our draft GSP and all the beneficial users have submitted their comment letters, now I get to have the envious task of going through all of them and making sure that the substantive comments are incorporated into our final GSP.”

Georgina King (Santa Cruz Mid County Basin) said this basin historically has kept in touch with its beneficial users, so they already knew what the issues would be. “Our advisory committee is comprised of a lot of different stakeholders; there is a representative from ag, from small private well owners, ratepayers, Chamber of Commerce, an environmental representative, and then there’s a at-large representative, so we try to get everyone involved. I think the County and the Mid County agencies have done a great job with flyers, similar things that we’ve heard here, in trying to get people interested and involved. In some cases, it’s difficult … In another basin I work in, hundreds go to the meetings, so every basin has its differences.”

AUDIENCE QUESTIONS

Question directed to Trey Driscoll (Borrego Spring): My mouth hit the table when you said you were going to have a 74% reduction in groundwater pumping. I’m curious to hear folks are responding that. What are they going to do?

Trey Driscoll (Borrego Springs): “The first question we get is ‘am I going to be able to take a shower?’ Is it going to impact my domestic use? That’s simply not the case in this basin. It’s a very large and deep basin; there’s millions of acre-feet of groundwater in storage. The basin has been mining groundwater, that’s very clear and that’s why we’re in critical overdraft, so we have developed a linear ramp down in reduction in pumping over time. The biggest user of groundwater is ag, so it’s primarily going to impact the ag sector. We are working through our projects and management actions, we are looking at a basin pumping allocation, and those allocations could be transferred over to the municipal or domestic users.”

“What I would say is that Borrego is fortunate enough to have a very large local resource,” Mr. Driscoll continued. “In some ways, we don’t have to rely on the Delta and we don’t have to rely on other users. The solution is local. But we do have sufficient water and good quality water, none of the water needs to be treated at this point in time in the basin to meet both municipal and domestic uses.”

Question: The one we can’t figure out minimum thresholds for is water quality. What are minimum thresholds when it comes to water quality and how do you address that?

Trey Driscoll (Borrego Springs): “I can tell you what’s in our plan. For municipal and domestic use, we have used the Title 22 water quality regulations for both water, and for ag and irrigation use, we’ve used water that’s suitable for that beneficial use.”

Georgina King (Santa Cruz Mid County Basin) agreed, saying in their basin, it is drinking water standards. “We have iron, manganese, arsenic, chromium, all naturally occurring, but in our plan, any increase in concentration that is related to something other than groundwater pumping or any project implemented as part of a plan, that’s nothing that the GSA can manage, so that’s dealt with separately. The Regional Water Quality Control Board covers that, so for us, so it’s only impacts from implementing the GSP. If it’s nature, it’s been there for millions of years, so there’s nothing we can do, although there are some basins where if we did ASR (aquifer storage and recovery), you can mobilize arsenic and so they are doing pilot testing and they do have to evaluate that specifically. Yes we have arsenic, but are we going to mobilize even more in the basin with their projects, so we have to make sure we address that.”

Amanda Peisch-Derby (Department of Water Resources) pointed out that if there is degraded water quality due to groundwater extraction, it’s going to have to be addressed somehow. “When you’re implementing projects or doing management actions, you’re going to have to consider the migration of contaminant plumes on drinking water supplies. You’ll have to demonstrate to the Department if those situations occur in your basin and you’re aware of water quality issues, you’re aware of plumes, how to fully address that indicator is determine how you’re going to ensure that an undesirable result doesn’t occur. Define your representative monitoring wells … you’ll either have to demonstrate that it doesn’t occur or you’re going to have to appropriately address that indicator in the plan.”

Question: In developing the sustainable management criteria, with each iteration, I’m wondering what went on behind the scenes -the models prepared, high level analysis of projects and management actions and costs, to set forth that criteria. How did that work?

Georgina King (Santa Cruz Mid County Basin): “In our basin, we didn’t want the projects and management actions to define sustainability. We tried to keep that out of it. We said, minimum thresholds, where do you not want to be, and then measurable objectives, where do you want to be in it. We tried to leave out the projections of the future out of it until the very end, and I think there’s only one, maybe the interconnected surface water, that’s the hardest one for us. We had to look and it’s hard to get the groundwater levels up in these shallow aquifers and so we had to look into the future, are the thresholds are we setting, are they achievable.”

Ronnie Samuelian (Kings Basin): “It was highly iterative. We did not get it right the first time and we’re not done. I think that’s a critical reminder. A lot of the stakeholders want to ask, what’s the answer? All we can do is decide, based on the best data we have. We have significant data gaps and we had spent a lot of our iterations going through what about this or can I find that or how about that and eventually you get to the point where you have to use the best information you have and make that recommendation now. We’re not done. This is version 1.0 early years. We have 20 years, and we’re going to learn a lot in that process, and I think a lot of us who do technical work understand that but getting that message out to the communities is hard, so it’s been very iterative.”

Trey Driscoll (Borrego Springs) echoed the approach. “We do have our draft out and it’s not perfect. We expect that over time, we’re going to adapt and need to revise potentially some of the thresholds. … They are talking about different ramp down schedules, so we’ve provided a guidance that will get to sustainability. If they agree to quicker ramp downs, that will only achieve it more quickly, but that’s something that’s on going and will be occurring throughout plan implementation.”

Question: The most difficult part to me is determining how to define what is significant and unreasonable, and where you draw the line. My question is for Georgina … you talked about significant and unreasonable for seawater intrusion being movement further than the recent 2013-2017 levels for seawater and for stream depletion; what was the policy making determined that going beyond those points would be significant and unreasonable? What criteria was looked at?

Georgina King (Santa Cruz Mid County Basin): “They’ve been managing seawater intrusion for a long time, so that policy had been made a long time ago. They didn’t want any more intrusion than what they were dealing with currently. It’s not impacting land uses, but they want to hold it where it is and preferably push it out if they could.”

The interconnected surface water depletions were much more challenging, Ms. King continued. “The question was what was it historically before we had data? Our data starts in the 80s, so what was it like then? We have no idea. The main thing is identifying that it’s not a losing reach anymore. It’s more technical, trying to understand the historic conditions and saying what do you want to avoid. We just recently went to the board with all the recommendations for all the SMCs, and we had some questions back from them that we had to address, but the board members have taken policy decisions seriously because the management we are proposing is similar to what they’ve done in the past, but the depletions of interconnected surface water, that’s a new one.”

Question: Given that the 2015 baseline occurred in the middle of the most serious drought, has anyone considered mitigating groundwater levels prior to 2015?

Ronnie Samuelian (Kings Basin): “I don’t know that the regs actually require you to mitigate to 2015 water levels. My understanding is that we have to move forward from 2015, but we’re not required to pull the water level back up to 2015, so we’re not. It’s just not practical in our area. We’re going to continue to decline, as long as we aren’t causing undesirable results, and that’s the key. That was a common misunderstanding, we had many board members and stakeholders coming to us and asking how we were going to get the water table back up that level, and the question is, are we causing undesirable results if it declines further, and that’s what our focus is on.”

Georgina King (Santa Cruz Mid County Basin): “Our basin is a little unique in that during the drought, our groundwater levels all rose, and it had nothing to do with the drought, it had to do with conservation. It was very successful … everyone who depends on groundwater, which is most of the basin, did a really tremendous job cutting back. There was groundwater level declines historically, but now they recovered that completely. So if there’s anything to take home from that, it’s with conservation and careful planning, you can get to those higher levels … “

FOR MORE INFORMATION …

- Learn more about SGMA implementation at the Groundwater Exchange.

- What’s involved in developing a Groundwater Sustainability Plan? Check out the steps here.

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!