Panel discusses the potential of stormwater as a resource, implementation of stormwater capture projects

Panel discusses the potential of stormwater as a resource, implementation of stormwater capture projects

Traditionally, stormwater has been viewed as a flood management problem that called for shunting off the floodwaters as quickly as possible from urban areas to waterways in order to protect public safety and property. However, as drought has put more pressure on water supplies and groundwater basins become depleted, stormwater is increasingly being seen as a potential way to recharge groundwater basins and augment local water supplies.

In 2011, the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) adopted the resolution, “A Comprehensive Response to Climate Change.” As one of the adaptation strategies, the Resolution called for managing stormwater as a resource. In 2014, SB 985 amended the Water Code to state that stormwater and dry weather runoff are “underutilized sources of surface water and groundwater supplies.” SB 985 also required the development of a stormwater resource plan as a condition of receiving grants for stormwater and dry weather runoff capture projects from Proposition 1.

At the April meeting of the California Water Commission, a panel discussed the implementation of stormwater projects across the state. Seated on the panel:

- Jeffrey Albrecht, project manager for the State Water Board’s Stormwater Strategy Unit, who discussed the Water Board’s strategy and projects to increases the use of stormwater capture and infiltration.

- Heather Cooley is Research Director at the Pacific Institute; she described some of the Institute’s recent reports on the potential for stormwater capture, as well as a recent study of commercial landscape potential in the Santa Ana watershed for stormwater capture.

- Keith Lilley, Assistant Deputy Director for Stormwater Planning for Los Angeles, who described Los Angeles County’s stormwater capture and infiltration projects.

- Don Bunts, Deputy General Manager for Santa Margarita Water District, described the San Juan Watershed Project, which will capture flood flows on ephemeral streams for groundwater infiltration.

JEFFREY ALBRECHT: Strategy to Optimize Resource Management of Stormwater (STORMS)

Jeffrey Albrecht is an engineer at the State Water Board in the Division of Water Quality and is the unit chief of the Strategy To Optimize the Resource Management of Stormwater or STORMS project.

Mr. Albrecht started with some background on the State Water Board’s stormwater program. In 2014, the State Water Board recognized the need to rethink their approach to stormwater permitting, one that would better recognize utilizing stormwater as a resource. So out of that emerged the Stormwater Strategic Initiative, which brought together a number of stakeholders to discuss the issues around stormwater.

Mr. Albrecht started with some background on the State Water Board’s stormwater program. In 2014, the State Water Board recognized the need to rethink their approach to stormwater permitting, one that would better recognize utilizing stormwater as a resource. So out of that emerged the Stormwater Strategic Initiative, which brought together a number of stakeholders to discuss the issues around stormwater.

The Stormwater Strategic Initiative identified four guiding principles: Treat stormwater as a valuable water resource; preserve watershed processes to achieve desired water quality outcomes; implement efficient and effective regulatory programs; and collaborate to solve water quality and pollutant problems utilizing an array of regulatory and non-regulatory approaches. As part of the initiative, 23 projects were identified and presented to the State Water Board; out of that in 2016, the STORMS program was developed with a ten-year time frame to implement the identified projects.

The vision of the STORMS program is that stormwater is sustainably managed and utilized in California to support water quality and water availability for human uses as well as the environment. To achieve that, the mission of the STORMS program is to lead the evolution of stormwater management in California by advancing the perspective that stormwater is a valuable resource, supporting policies for collaborative watershed-level stormwater management and pollution prevention, removing obstacles to funding, developing resources, and integrating regulatory and non-regulatory interests.

The STORMS program has six objectives:

- Increase stormwater capture and use through regulatory and non-regulatory approaches

- Increase stakeholder collaboration on a watershed scale

- Establish permit pathways to assess stormwater programs and meet water quality requirements

- Establish financially sustainable stormwater programs

- Improve and align State Water Board oversight of Water Board programs and water quality planning efforts

- Increase source control and pollution prevention

The slide on the lower shows the 23 projects identified as part of the STORMS program, which are categorized as to the objective the particular project addresses. The STORMS program is a ten year project to be completed in three phase; the green highlights the projects identified for the first phase.

The slide on the upper right are the nine projects identified in phase one. Mr. Albrecht said of the nine, five are of interest to the Commission and highlighted in yellow, so he would be giving an update on the progress made on those five projects.

He first gave some background on the issue. At the State Water Board, their primary objective is water quality and protecting surface waters. In the natural environment when it rains, the soil gives a chance for the water to slow down and infiltrate and recharge the groundwater aquifer (lower, left). However, in the highly urbanized environment, there are large buildings such as big box stores with large roofs and adjacent large parking lots, which results in the fast tracking of stormwater out to the waterways, picking up pollutants along the way (lower, right)

“The result is that you’ve lost the opportunity to infiltrate that water, and you’ve also increased the impacts on your surface waters,” Mr. Albrecht said. “So the conclusion is that we have really devalued water in these urban areas, and this is what we’re trying to reverse with the things the STORMS program is trying to promote.”

There are a number of stormwater control measures or Low Impact Development strategies. These include vegetated swales, stormwater planters, rain gardens, permeable pavement, infiltration chambers and the dry wells.

There are a number of stormwater control measures or Low Impact Development strategies. These include vegetated swales, stormwater planters, rain gardens, permeable pavement, infiltration chambers and the dry wells.

“The vegetated swale is a chance to do a pass through healthy soils and slow it down,” Mr. Albrecht said. “Stormwater planters are a more engineered type feature. The rain gardens are a watershed scale and have a bigger footprint; they can be developed as a feature. Permeable pavement lets you develop those parking lots but it also can be combined with some underground infiltration capacity, and then infiltration chambers is really trying to get to large volume. The picture is of underground cells, but they can go all the way to the large walk-in type vault systems; the goal of all those projects trying to keep those pollutants close to the source but combining with that infiltration capacity. Dry wells are meant to give it a chance to infiltrate possibly getting past an impermeable layer of clay into the subsurface, but still trying to keep you separated from the aquifer level.”

Projects 1A and 1B relate to objective one, which is eliminating regulatory and political barriers facing stormwater capture and use. To support that, the State Water Board has a contract with Sacramento State’s Office of Water Programs to research and develop a report. Mr. Albrecht noted that the Office of Water Programs has a lot of great resources, including the Environmental Finance Center which is an arm of the US EPA to help develop resources for funding of stormwater and other water programs.

Projects 1A and 1B relate to objective one, which is eliminating regulatory and political barriers facing stormwater capture and use. To support that, the State Water Board has a contract with Sacramento State’s Office of Water Programs to research and develop a report. Mr. Albrecht noted that the Office of Water Programs has a lot of great resources, including the Environmental Finance Center which is an arm of the US EPA to help develop resources for funding of stormwater and other water programs.

The report from Office of Water Programs had six recommendations for the State Water Board:

- Explore options for funding stormwater capture and use

- Resolve regulatory and policy issues related to the use of drywells for stormwater management. A lack of guidance was identified, so in response, the STORMS program has a contract with Geosyntec to develop guidance for using dry wells, including siting, design, and monitoring. They are also exploring the potential impact of water rights on stormwater capture and use

- Expand/improve regulatory performance measurements to reflect capture and use objectives

- Establish a framework to assess local ecological impacts, positive and negative, to capture and use diversions

- Improve consideration of (even quantify) urban stormwater capture and use in Integrated Regional Water Management Plans (IRWMPs)

- Require that capture and use planning for developers and municipal planners be adopted into city and county ordinances governing entitlements

Projects 4A and 4B relate to the objective surrounding funding. SB 985 passed in 2014 modified stormwater planning, permitting, and funding programs to support priority actions identified in Stormwater Resource Plan Guidelines. SB 985 also required Stormwater Resource Plans to be developed in order to qualify for voter approved bond funds; the plans were intended to gather the water interests in the region together to collaborate and support the development of multi-benefit projects. Another piece was identifying barriers to stormwater funding, such as Prop 218.

Projects 4A and 4B relate to the objective surrounding funding. SB 985 passed in 2014 modified stormwater planning, permitting, and funding programs to support priority actions identified in Stormwater Resource Plan Guidelines. SB 985 also required Stormwater Resource Plans to be developed in order to qualify for voter approved bond funds; the plans were intended to gather the water interests in the region together to collaborate and support the development of multi-benefit projects. Another piece was identifying barriers to stormwater funding, such as Prop 218.

The outcome was a report presented to the Board that had eight recommendations for next steps. To address the first recommendation, SB 231 was developed to address the Prop 218 barrier regarding the development of fees. “Within Prop 218, it states that water, solid waste, and sewer are exempt from the more restrictive fee development for municipalities and SB 231 clarifies that when they state sewer, that is inclusive or stormwater,” Mr. Albrecht said. “This new language has not been really tested by anyone through the legal courts so we’re still trying to track it to see if a city can successfully navigate through that fee development process and see what challenges it faces legally. Many cities just don’t have those stormwater fees in place to develop these types of projects.”

The second recommendation involved the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund, which is about drinking water supply, but it does cover the realm of water source enhancement which includes stormwater, he said. “We’ve been trying to bridge this gap of how do we get our Drinking Water SRF folks more familiar with these types of projects and making sure there is a clear path through the application process.”

Mr. Albrecht acknowledged that there is a misalignment as the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund states that dams and reservoirs are ineligible without any further clarification; however, inflatable dams are used to capture dry weather and stormwater runoff.

“The piece of that we’re working on is the use of an inflatable dam which is not really consistent with what’s being defined within the DWSRF handbook,” he said. “We’re trying to address that as one of the small pieces that would open up new opportunities.”

The fifth project is about open data and improving the access, quality, and quantity of the data. He acknowledged that many parts of the program would be better informed if there was good data on how well stormwater control measured performed with metrics such as infiltration rates, as well as how effectively they addressed specific pollutants. He also noted the State Water Board’s climate change resolution directed the Division of Water Quality to develop a methodology to figure out how much stormwater is being captured and used statewide. To support that, the State Water Board has a contract with Southern California Coastal Water Research Project to develop data standards so as monitoring is conducted for stormwater projects, the data collected is more consistent and comparable, and can provide the foundation for future regulatory efforts and the development of Best Management Practices.

The fifth project is about open data and improving the access, quality, and quantity of the data. He acknowledged that many parts of the program would be better informed if there was good data on how well stormwater control measured performed with metrics such as infiltration rates, as well as how effectively they addressed specific pollutants. He also noted the State Water Board’s climate change resolution directed the Division of Water Quality to develop a methodology to figure out how much stormwater is being captured and used statewide. To support that, the State Water Board has a contract with Southern California Coastal Water Research Project to develop data standards so as monitoring is conducted for stormwater projects, the data collected is more consistent and comparable, and can provide the foundation for future regulatory efforts and the development of Best Management Practices.

Another piece is determining where the data repository will be and identifying what additional resources are out there for providing the data. “How can we drive folks to provide that data collection,” he said. “It’s going to require monitoring, but monitoring can be onerous expensive, and there are a number of issues there as well.”

The STORMS program has an Implementation Committee which is the forum for working with stakeholders. They meet quarterly to discuss projects and to receive feedback loop as to where things are going. This has really been a great way to bring together those variety of interests. “We have the water, we have sanitation, we have the business, and we have the environmental interests at the table addressing these projects, and really trying to help us guide or inform or direct how these STORMS program projects are developed,” Mr. Albrecht said.

He concluded by displaying a slide showing the proposed phase two projects they are starting to discuss and strategize how to implement.

He concluded by displaying a slide showing the proposed phase two projects they are starting to discuss and strategize how to implement.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

HEATHER COOLEY: Urban Runoff Opportunities

Heather Cooley is the Director of Research with the Pacific Institute, an independent non-profit research organization based in Oakland whose mission is to create and advance solutions to the world’s pressing challenges; the Pacific Institute does work in California as well as in communities around the world to advance their mission.

Heather Cooley is the Director of Research with the Pacific Institute, an independent non-profit research organization based in Oakland whose mission is to create and advance solutions to the world’s pressing challenges; the Pacific Institute does work in California as well as in communities around the world to advance their mission.

Ms. Cooley focused her remarks on urban runoff, which historically has been treated as a liability resulting in the channelization of waterways which sought to remove that water as quickly as possible. However, this process has created water quality issues because the runoff is picking things up off the pavement along with the fertilizers and pesticides that are used on landscapes. And as the effects of climate change intensify, there are increasing flooding concerns. In addition, the opportunities to recharge groundwater have also been cutoff, which is an important water supply for communities.

However, Ms. Cooley said there was increasing interest in recognizing stormwater as an asset, while at the same time addressing the water quality and flooding issues. The Pacific Institute started researching this in 2014 with the report, The Untapped Potential of California’s Water Supply which looked at opportunities for water efficiency and water reuse as well as stormwater capture. The project, a partnership with the Natural Resources Defense Council, determined that there was an opportunity in the Bay Area and Southern California for boosting supplies by about 420,000 to 630,000 acre-feet.

She noted that the study was focused on opportunities for capturing water from impervious surfaces; they also looked at opportunities for recharging groundwater using soil classification as an indicator.

She noted that the study was focused on opportunities for capturing water from impervious surfaces; they also looked at opportunities for recharging groundwater using soil classification as an indicator.

“In some parts of the state, they are fortunate enough to have those opportunities in a number of communities,” she said. “However, there are some communities that don’t, and in those places, capturing urban runoff for direct use, using rainwater cisterns or tanks or other mechanisms is an opportunity.”

Ms. Cooley also pointed out that the study only evaluated the Bay Area and Southern California which only represents about 75% of the urbanized spaces in California; there are surely opportunities in the areas that were not mapped, but the study represents a fairly conservative effort of what is possible.

A follow-up study was completed in 2016 that looked at the costs of various water supply and efficiency opportunities. The slide shows the cost range of both residential and commercial efficiency measures; the cost shown are levelized which means that the cost of conserved water is calculated from efficiency savings based on the incremental cost of purchasing and installing a new water-efficient device and any changes in operation and maintenance costs resulting from the investment (excluding water bill payments). This cost is annualized over the life of the device and divided by the average annual volume of water conserved, resulting in an estimate of the cost of conserved water expressed in dollars per acre-foot of water.

A follow-up study was completed in 2016 that looked at the costs of various water supply and efficiency opportunities. The slide shows the cost range of both residential and commercial efficiency measures; the cost shown are levelized which means that the cost of conserved water is calculated from efficiency savings based on the incremental cost of purchasing and installing a new water-efficient device and any changes in operation and maintenance costs resulting from the investment (excluding water bill payments). This cost is annualized over the life of the device and divided by the average annual volume of water conserved, resulting in an estimate of the cost of conserved water expressed in dollars per acre-foot of water.

Some efficiency measures have a “negative” cost, which means the total benefits, including non-water benefits that accrue over the lifetime of the device, exceed the cost of the water efficiency investment. This is especially true for efficiency measures that save customers energy, but also for those that provide savings in labor, fertilizer or pesticide use, and reductions in wastewater treatment costs. For example, a high-efficiency clothes washer costs more than a less-efficient model; however, over its lifetime it uses less energy and produces less wastewater than inefficient models, thereby reducing household energy and wastewater bills. Over the estimated 14-year life of the device, the reductions in energy and wastewater bills are more than sufficient to offset the cost of the more efficient model, resulting in a negative cost of conserved water.

The study also looked at the cost of various water supply projects. They pulled data from existing projects whenever possible, but in some cases they had to use proposed projects. She acknowledged that data was definitely an issue.

“The broad findings from the study are that we still in California have tremendous opportunities around efficiency and in fact, those tend to be our most cost effective options,” Ms. Cooley said. “When we look at the supply options, we see a lot of variability in project costs driven by some site specific factors, but we see in general seawater desalination at the higher end of the range, stormwater capture at the lower end, although there are somewhat in that middle, and reuse in the middle there. And of course, there is some variability there, but I do think this gives you a sense of that the costs are.”

“The broad findings from the study are that we still in California have tremendous opportunities around efficiency and in fact, those tend to be our most cost effective options,” Ms. Cooley said. “When we look at the supply options, we see a lot of variability in project costs driven by some site specific factors, but we see in general seawater desalination at the higher end of the range, stormwater capture at the lower end, although there are somewhat in that middle, and reuse in the middle there. And of course, there is some variability there, but I do think this gives you a sense of that the costs are.”

She acknowledged that there’s not a lot of information or data around cobenefits, which is important for stormwater capture. Oftentimes, only the flood control, the water quality, and increasingly the water supply benefits are considered, and in some cases, only one of those benefits is considered. “We’re not fully understanding what the benefits are that these provide, and really how cost effective they can be when you start to think about it more broadly,” she said.

Ms. Cooley also pointed out that stormwater projects can provide non-water benefits, such as providing wildlife habitat in urbanized areas; increasing groundwater levels and thereby reducing the energy requirements for pumping which in turn reduces the greenhouse gas emissions associated with that energy; or reducing the urban heat island effect which can reduce building cooling requirements and the greenhouse gas emissions associated with that. There can be opportunities to improve air quality, increase property values, and enhance community liability as well, she said. They are currently working to develop a framework for integrating the co-benefits from a variety of water projects in the water space.

Ms. Cooley noted that they will be releasing a study later this year that looks at the cost of stormwater capture with and without cobenefits. The data for that study came from rounds 1 and 2 of Prop 1E and Prop 84 project proposals; they included both the submitted costs as well as some of the benefits.

“In looking at the benefits, we don’t have a tremendous amount of consistency,” she said. “We don’t have standards around how benefits are either evaluated or reported, so I will issue the caveat that we didn’t independently verify each of these benefits. I do think there’s some work that could be done around standardizing benefit reporting, but we did work with the data that was available. We looked at about 50 projects, about half of the projects addressed urban runoff and the rest of the projects dealt with non-urban runoff.”

Most of the urban runoff projects they looked at were in Southern California, although a few were in the Central Valley as well. The right side shows the urban runoff capture projects. The cost on a dollar per-acre foot basis was derived from taking the full cost and dividing by the water supply benefit.

Most of the urban runoff projects they looked at were in Southern California, although a few were in the Central Valley as well. The right side shows the urban runoff capture projects. The cost on a dollar per-acre foot basis was derived from taking the full cost and dividing by the water supply benefit.

“When we did that, we found for those projects that the cost was around $1230 an acre-foot,” she said. “That was quite consistent with our earlier study. However, when we included the co-benefits, we found that the cost was around $230 an acre-foot, so a tremendous opportunity on the order of about $1000 per acre-foot of benefit from these non-water supply benefits.”

Ms. Cooley noted that even though the data used was better and they did include some benefits, they still weren’t all inclusive. “There were still a number of cobenefits that weren’t even captured, so as we start to think about the investments we need to make in California related to water supply and water quality, there is a real opportunity to look to these types of projects.”

In February of 2019, the Pacific Institute released the report, Sustainable Landscapes on Commercial and Industrial Properties in the Santa Ana River Watershed. “When we use the term, sustainable landscapes, we’re talking about taking out water intensive turf grass, putting in climate appropriate plants, but also implementing some stormwater BMPs, things such as bioswales, rain gardens, and permeable pavement,” she said. “These commercial and industrial properties tend to have large expanses of impervious surfaces and a lot of turf as well, in fact turf that no one’s really using, so there is a real opportunity for us to start using those to capture stormwater and to improve water sustainability more broadly.”

In February of 2019, the Pacific Institute released the report, Sustainable Landscapes on Commercial and Industrial Properties in the Santa Ana River Watershed. “When we use the term, sustainable landscapes, we’re talking about taking out water intensive turf grass, putting in climate appropriate plants, but also implementing some stormwater BMPs, things such as bioswales, rain gardens, and permeable pavement,” she said. “These commercial and industrial properties tend to have large expanses of impervious surfaces and a lot of turf as well, in fact turf that no one’s really using, so there is a real opportunity for us to start using those to capture stormwater and to improve water sustainability more broadly.”

As part of the project, they mapped the watershed to understand where regions suitable for groundwater recharge are located while also considering areas that were already in the 100 or 500 year flood zones where these types of projects would be especially useful. They also looked at areas near impaired waters where these types of projects can provide a water quality benefit. They then overlaid the location of disadvantaged communities to identify where these types of projects might provide some benefits to those communities. They also performed a more detailed parcel-level analysis to better understand what the opportunities are on commercial and industrial parcels.

As part of the project, they mapped the watershed to understand where regions suitable for groundwater recharge are located while also considering areas that were already in the 100 or 500 year flood zones where these types of projects would be especially useful. They also looked at areas near impaired waters where these types of projects can provide a water quality benefit. They then overlaid the location of disadvantaged communities to identify where these types of projects might provide some benefits to those communities. They also performed a more detailed parcel-level analysis to better understand what the opportunities are on commercial and industrial parcels.

Historically, much of the work around stormwater capture has really been focused more on centralized infrastructure opportunities, but there are opportunities on private property and on these commercial and industrial properties which tend to have large expanses of impervious surfaces.

“We found in the Santa Ana watershed, the average commercial and industrial property had about 90,000 square feet of impervious surface and about 5500 square feet of turf grass,” Ms. Cooley said. “It was not normally distributed, though. There were about 1000 properties that had over 100,000 square feet of turf grass, so there is a further opportunity to start targeting and focusing in on areas where there are large impervious surfaces and large areas of potential landscape that could be converted.”

The business community has several motivations for moving forward on stormwater projects. Those motivations can include financial savings, possible stormwater fees that could be avoided, and an interest in social responsibility.

Focusing on the commercial and industrial properties also presents the opportunity to leverage private capital; there’s also an interest in enhancing reputation as being seen as a leader can benefit a business in meeting its sustainability goals.

“We interviewed businesses as part of this work, and many of them see themselves as members of the community,” she said. “They want to help address some of the issues and challenges they know they are experiencing and some of the risks that they face.”

There is a free online interactive map that allows business owners or the public to type in an address and find out if a project might help provide a water supply, a water quality, or a flood risk management benefit; it also will identify if the property is in a disadvantaged community.

There is a free online interactive map that allows business owners or the public to type in an address and find out if a project might help provide a water supply, a water quality, or a flood risk management benefit; it also will identify if the property is in a disadvantaged community.

They are now working with business owners in the region to try to advance some of the projects and provide technical assistance, especially with monitoring and evaluation. “We don’t have a lot of great data on these projects and so we see this as an opportunity to start to evaluate some of the benefits and cobenefits, and to really start to make that available so that others can make more informed decisions,” she said.

In terms of implementation barriers, one common theme is related to funding and the challenges with Prop 218 in particular. Another challenge is the fragmentation in the water sector; the benefits accrue to multiple agencies so it does require some collaboration and coordination and that can be challenging. There can also be institutional barriers, which can make it difficult to cross funds, she said.

In terms of implementation barriers, one common theme is related to funding and the challenges with Prop 218 in particular. Another challenge is the fragmentation in the water sector; the benefits accrue to multiple agencies so it does require some collaboration and coordination and that can be challenging. There can also be institutional barriers, which can make it difficult to cross funds, she said.

Another challenge is incomplete consideration of cobenefits. “In some cases, we’re quantifying them, in some places we’re not, so there is just a lot of inconsistency and there’s not a standardization in methods, or at least even an agreed upon set of methods we might use to do so,” Ms. Cooley said. “There also tends to be a bias towards these large centralized projects, but what we are ignoring are some of the opportunities for decentralized projects. I don’t think its one or the other; I think it’s a both. I think the sustainability challenges we face in our communities and in our state are such that we really need all people to be thinking about where they might be able to contribute.”

Land use presents another implementation barrier; some of the land use policies that we currently have that are still failing to protect recharge areas, she said. “We have a lot of development already in California and we’re growing and urbanizing, and so that puts more areas at risk potentially cutting off that recharge. We don’t yet have universal implementation of some of these low impact development BMPs, either.”

Ms. Cooley then gave her conclusions. “Stormwater capture can boost our local water supplies,” she said. “It can also provide important water and non-water cobenefits, and I think those are critical in moving these projects forward. It’s cost effective, especially when we start to capture these cobenefits. Fourth, I think we really need to start valuing both centralized and decentralized options in looking for opportunities for those to be coordinating. And five is related to partnerships and collaboration; they are essential for these types of projects and it’s how we’re going to optimize our investments by bringing partners in. Also, we need to be thinking more than just about partnering among agencies but thinking about the community as well, because they too can contribute to helping us.”

Ms. Cooley then gave her conclusions. “Stormwater capture can boost our local water supplies,” she said. “It can also provide important water and non-water cobenefits, and I think those are critical in moving these projects forward. It’s cost effective, especially when we start to capture these cobenefits. Fourth, I think we really need to start valuing both centralized and decentralized options in looking for opportunities for those to be coordinating. And five is related to partnerships and collaboration; they are essential for these types of projects and it’s how we’re going to optimize our investments by bringing partners in. Also, we need to be thinking more than just about partnering among agencies but thinking about the community as well, because they too can contribute to helping us.”

Commissioner Ball asked how stormwater can be captured and reused. Ms. Cooley replied that there are several ways; one way is to divert water that falls on impervious surfaces such as roofs or parking lots and diverting that into an area where it can infiltrate. “Part of it is about healthy soils that are able to capture and store that water. I think there are even areas now where the soil is so compact, even though it’s a natural looking landscape, it may not be absorbing, so part of it is around soil health; part of it is diverting some of the water that’s currently falling on impervious surfaces into those areas. It can be taking out some of the impervious pavement and putting in permeable pavement that allows for some of that to infiltrate. In some areas where that is not an option or in addition to that, you can also have these rainwater cisterns or rainwater tanks at a smaller level, so I think there are a number of strategies that can be adopted to either boost recharge or capture it so it’s available for reuse.”

Commissioner Quintero asked if the Pacific Institute looking at models for incentives.

“We have looked at some incentives,” said Ms. Cooley. “We had another project that looked at various incentives that are available in communities, and in some cases, there are regulations when it comes to new development for example in requiring curb cuts and etc. As part of our work on commercial and industrial properties, we are starting to evaluate incentives, and as we work with companies in trying to get these implemented, we’re trying to evaluate the value of those. When we did interviews, many said across the board, incentives would be helpful. In some cases, those incentives were available and they didn’t even know about it. So part of it is communication and making sure people are aware of the existing incentives, but then also providing incentives where we can. We have to be careful in how we provide incentives, and we want to do it in part to move the market, and we want to be targeted to make sure we’re getting the most bang for our buck. I do think there is an important role for incentives, particularly in these early days as we are trying to get these projects up and running.”

MARTHA DAVIS adds …

Martha Davis, who worked for the Inland Empire Utilities Agency which is located in the Upper Santa Ana River watershed for 17 years, gave a few comments. “The question about engineered focused recharge and the most distributed recharge, it’s a both-and,” she said. “In my service area, we did focus on capture of dry water and stormwater. In fact, our recharge basins use the inflatable dams, and our first priority was capturing stormwater. Our second priority was using recycled water, and the third priority was using imported water as part of augmenting the recharge, so we actually did it in a blended way. But that didn’t mean that we were capturing all of the runoff that was available to be captured. We actually found in updating of the groundwater management planning, that because of hard surfaces not capturing as well as we could, we were still seeing declining levels in the groundwater, the safe yield. So it becomes really important to think in a watershed approach and how you hold back this water, because you’re not going to be able to do it all in a concentrated way. You’re going to need to be able to do it in other ways.”

“We found in our area that when we were conserving water during the drought, which was primarily landscape conservation, we ended up reducing the amount of water that we need to pump out of the groundwater basin, so ironically, our groundwater basin went up during the drought,” Ms. Davis continued. “If there are ways of better managing our water supplies so we have landscaping that is both efficient and maximizing the capture of rain water when we can capture it, it actually changes some of the way in which we’re operating our groundwater basins, allowing us to hold more water back in preparation for that next drought. So all of these pieces really fit together nicely.”

“We found in our area that when we were conserving water during the drought, which was primarily landscape conservation, we ended up reducing the amount of water that we need to pump out of the groundwater basin, so ironically, our groundwater basin went up during the drought,” Ms. Davis continued. “If there are ways of better managing our water supplies so we have landscaping that is both efficient and maximizing the capture of rain water when we can capture it, it actually changes some of the way in which we’re operating our groundwater basins, allowing us to hold more water back in preparation for that next drought. So all of these pieces really fit together nicely.”

Ms. Davis said there is a project going forward that is a partnership between the California Water Efficiency Partnership and the Community Water Center, looking at the opportunity of working in disadvantaged communities and targeting what are the projects that could be done in those areas for doing a better job of capturing stormwater. “What we’re encouraging is that when we get rain, we’re irrigating the landscaping with that water, rather than being dependent on always having to have augmented irrigation to maintain healthy landscapes and landscapes that have food. Because I think we’re going to want to connect it with that, and also connect it with trees, particularly in hot interior areas where we really need to value our legacy oaks and other landscaping. It’s going to make such a difference in dealing with the rising temperatures of climate change.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION …

- Pacific Institute Report: The Untapped Potential of California’s Water Supply

- Pacific Institute Report: Sustainable Landscapes on Commercial and Industrial Properties in the Santa Ana River Watershed

KEITH LILLEY, Stormwater Capture in LA County

Keith Lilley is the Assistant Deputy Director for Stormwater Planning for Los Angeles. In his role at LA County Public Works, he oversees integrated water resource planning for the Los Angeles County Flood Control District. In his presentation, he discussed the District’s efforts at stormwater capture and recharge, and highlighted some of the infrastructure improvement projects that have been constructed to enhance stormwater capture and local water supply.

The Los Angeles County Flood Control District was formed by the state in 1915 after a series of devastating floods in Los Angeles. The LA Basin is a floodplain with stormwater running off the mountains, and the flow path varied dramatically during intense storm periods which really challenged the ability for development. Following those significant storm events, the last one being a large flood in 1914, the Flood Control District was formed to reduce risks by providing flood protection. At the time, they also had the foresight to give the district a dual mission to both prevent flooding and to capture and conserve floodwaters for water supply.

The Los Angeles County Flood Control District was formed by the state in 1915 after a series of devastating floods in Los Angeles. The LA Basin is a floodplain with stormwater running off the mountains, and the flow path varied dramatically during intense storm periods which really challenged the ability for development. Following those significant storm events, the last one being a large flood in 1914, the Flood Control District was formed to reduce risks by providing flood protection. At the time, they also had the foresight to give the district a dual mission to both prevent flooding and to capture and conserve floodwaters for water supply.

The map shows the locations of the facilities which are located mostly in the mountains and foothills. There are 14 major dams that hold the water during storm events to be released afterwards; there are 500 miles of open channels that were designed to capture the runoff from the area and rush it to the ocean as quickly as possible; there are 26 spreading basins where stormwater can be recharged into the groundwater; and they also have seawater intrusion barriers.

The map shows the locations of the facilities which are located mostly in the mountains and foothills. There are 14 major dams that hold the water during storm events to be released afterwards; there are 500 miles of open channels that were designed to capture the runoff from the area and rush it to the ocean as quickly as possible; there are 26 spreading basins where stormwater can be recharged into the groundwater; and they also have seawater intrusion barriers.

He noted that their dams are a lot smaller than a lot of the state dams. During a wet storm season, the reservoir is often filled up, drained and recharged to groundwater multiple times.

It’s also not unusual during a large storm event that dam will fill and the flows will go down the spillway; there are spillway flows every 5 to 7 years, he said.

Some of the channels are completely engineered concrete channels; others are soft bottom channels. The picture is of the San Gabriel River where the sides are armored to control the flow but the bottom is soft and water is allowed to infiltrate. In addition to the natural infiltration, they have inflatable rubber dams to hold the water back so it will have more time to infiltrate. In the picture on the right, the rubber dam is inflated and a side-channel is opened to divert the water into one of the spreading grounds.

Some of the channels are completely engineered concrete channels; others are soft bottom channels. The picture is of the San Gabriel River where the sides are armored to control the flow but the bottom is soft and water is allowed to infiltrate. In addition to the natural infiltration, they have inflatable rubber dams to hold the water back so it will have more time to infiltrate. In the picture on the right, the rubber dam is inflated and a side-channel is opened to divert the water into one of the spreading grounds.

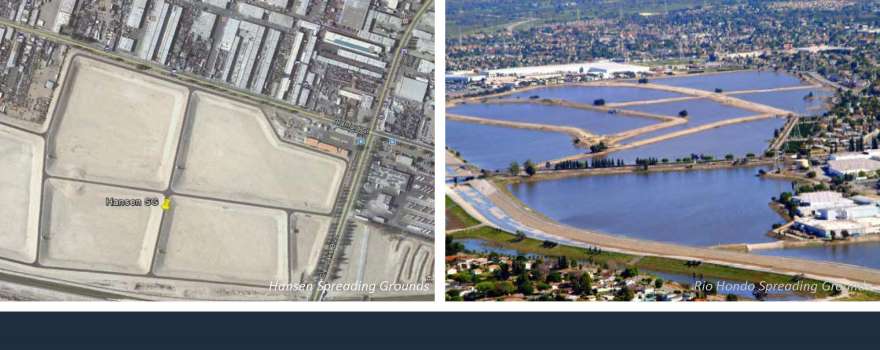

The Flood Control District essentially pioneered large scale artificial recharge in the 1930s. They now have 26 spreading grounds, a total of 2200 acres of basins located strategically throughout the county where there are opportunities to recharge the groundwater aquifers.

The slide on the upper right is a map of the groundwater basins. Almost all the groundwater basins are adjudicated; there are a few smaller basins that were not adjudicated and are going through the SGMA process now.

With the spreading grounds, they can capture about 200,000 acre-feet a year of stormwater. The basins are also used to infiltrate imported water and recycled water.

With the spreading grounds, they can capture about 200,000 acre-feet a year of stormwater. The basins are also used to infiltrate imported water and recycled water.

“We don’t own water rights at the flood control district,” Mr. Lilley said. “We don’t pump water; the groundwater managers handle that. They make the calls as to where the move the imported water and we do that for them to facilitate it.”

With that 200,000 acre-feet of stormwater capture plus the natural infiltration and other efforts in the region, groundwater provides about one-third of the local water supplies; two-thirds is imported from Northern California and the Colorado River.

With only one-third of the water supply coming from local sources, there were concerns about drought or periods when imported water may not be available, so the region recognized the need to do more to increase local water supplies. Starting around 2000, they aggressively started implementing a program to increase local water supplies through improvements of our dam infrastructure. Several of our dams had seismic restrictions that limited how much water could be held behind the dam, so they performed seismic upgrades so they can take full advantage of the reservoir capacity. They also upgraded the inlet-outlet works to better match outflow rates so they can take more water at the spreading grounds. They have also done sediment removal projects to increase capacity.

With only one-third of the water supply coming from local sources, there were concerns about drought or periods when imported water may not be available, so the region recognized the need to do more to increase local water supplies. Starting around 2000, they aggressively started implementing a program to increase local water supplies through improvements of our dam infrastructure. Several of our dams had seismic restrictions that limited how much water could be held behind the dam, so they performed seismic upgrades so they can take full advantage of the reservoir capacity. They also upgraded the inlet-outlet works to better match outflow rates so they can take more water at the spreading grounds. They have also done sediment removal projects to increase capacity.

There have been numerous projects to improve the spreading grounds by deepening and enlarging them to improve operations efficiencies. They have also made enhancements to their seawater barriers.

The Tujunga Dam Seismic Retrofit Project was completed in 2011; it increased stormwater capture 4500 acre-feet on average. The construction costs of $88.5 million included $17.4 million from the state and FEMA hazard mitigation grant, $6.6 million from the state’s Prop 13, and the City of Los Angeles contributed $9 million.

The Tujunga Spreading Grounds Project is under construction right now. The basins are being enlarged and deepened, and with the increased operational efficiency, capacity will be doubled to about 12,000 acre-feet per year. The City of LA actually owns the spreading facility; the Flood Control District operates and maintains it for them, as well as manage the construction project. The city contributed $40 million, $30 million came from a Prop 84 grant, and $6.3 million was contributed by Department of Public Works and the Flood Control District.

For the seawater barriers, the diagram shows the injection well where it creates a pressure to separate the seawater from the groundwater basin through a series of 300 injection wells. They have been systematically upgrading those to perform better, as well as transitioned those to tertiary treated recycled water rather than potable water. Mr. Lilley noted that they are almost 100% transitioned to recycled water.

For the seawater barriers, the diagram shows the injection well where it creates a pressure to separate the seawater from the groundwater basin through a series of 300 injection wells. They have been systematically upgrading those to perform better, as well as transitioned those to tertiary treated recycled water rather than potable water. Mr. Lilley noted that they are almost 100% transitioned to recycled water.

The Flood Control District chairs the Greater Los Angeles County Integrated Regional Water Management (IRWM) group as well as the Antelope Valley IRWM group. So far they have been successful in getting about $127 million in funding for 74 projects, most of which are water quality and water conservation based, he said.

Looking ahead, the District conducted a study in cooperation with the Bureau of Reclamation that considered all the different opportunities in Los Angeles County given climate change and the need for adaptation. “They identified perhaps up to three times the amount of water could be conserved through different practices such as putting large stormwater capture facilities in, putting rubber dams on our existing dams to further increase the amount water we could capture, and then distributed stormwater capture, smaller scale capture,” Mr. Lilley said. “Additionally, the City of Los Angeles has their sustainability plan where they are looking at by 2035, having 50% of their water supply be local supply.”

Looking ahead, the District conducted a study in cooperation with the Bureau of Reclamation that considered all the different opportunities in Los Angeles County given climate change and the need for adaptation. “They identified perhaps up to three times the amount of water could be conserved through different practices such as putting large stormwater capture facilities in, putting rubber dams on our existing dams to further increase the amount water we could capture, and then distributed stormwater capture, smaller scale capture,” Mr. Lilley said. “Additionally, the City of Los Angeles has their sustainability plan where they are looking at by 2035, having 50% of their water supply be local supply.”

In November 2018, the voters approved a parcel tax that is expected to generate $300 million per year in perpetuity to fund stormwater projects through the Safe Clean Water Program. “One of the reasons for its success was that it was generated from the need to comply with the MS-4 permits and the municipalities not having a dedicated funding source to address the stormwater quality issues,” he said. “However, when we started working with stakeholders looking at the potential funding mechanism, communities were really concerned that this program be broader than just water quality; it needed to have some additional benefits, and water supply was a significant component of that, as well as community enhancements. So the idea of having nature-based solutions where this new stormwater infrastructure can both capture clean water and provide habitat, have open space, have recreation areas, those types of things are a huge push in helping get the stakeholders on board. It was ultimately passed by 69% of the voters.”

The Safe Clean Water Program is funded by a parcel tax of 2.5 cents per square foot of the impermeable area; all the parcels in the county have been analyzed and the percent impervious surfaces calculated and the tax determined for each individual parcel.

The Safe Clean Water Program is funded by a parcel tax of 2.5 cents per square foot of the impermeable area; all the parcels in the county have been analyzed and the percent impervious surfaces calculated and the tax determined for each individual parcel.

Of the revenues generated from the tax, 50% of that funding will go towards regional projects in that watershed. For each city, 40% of the money generated in the city will go back to the city to implement projects. The remaining 10% will go to the Flood Control District to administer the program, run educational programs and training programs, provide resources to the municipalities and the regional program, and to implement some flood control district programs.

The projects envisioned for the program range from large and medium scale down to the neighborhood scale. The Dominguez wetlands was an old spreading ground that didn’t function very well. It was converted to a wetland, so now it diverts the flow and treats it; there are community amenities such as walking paths, areas to recreate, and shade structures. At Bassett High School, they built large underground infiltration basins underneath the ball fields. The Elmer Avenue green street is a neighborhood project where they put in a green street to divert stormwater runoff, and flow through a natural area as an alternative to a grass parkway.

The projects envisioned for the program range from large and medium scale down to the neighborhood scale. The Dominguez wetlands was an old spreading ground that didn’t function very well. It was converted to a wetland, so now it diverts the flow and treats it; there are community amenities such as walking paths, areas to recreate, and shade structures. At Bassett High School, they built large underground infiltration basins underneath the ball fields. The Elmer Avenue green street is a neighborhood project where they put in a green street to divert stormwater runoff, and flow through a natural area as an alternative to a grass parkway.

One of the challenges for the Los Angeles region is adapting to climate change. “We expect perhaps similar average annual rainfall but not average rainfall in any year, more longer periods of drought and more intense storms when they do happen which means more challenges in capturing that water when it is available,” Mr. Lilley said. “Secondary issue is the fire flood sequence which has a significant impact on Los Angeles County areas, especially our dams and debris basins where after the fires, you get this tremendous mud flows that fill the reservoirs.”

The picture on the lower left shows the Big Tujunga Dam after the 2009 Station Fire; the watershed around the reservoir area was completely burned. Obtaining permits to remove the sediment was tremendously challenging, he said. “There were increasing regulatory issues and understandably so with endangered species in the area, and so there’s interest in dedicating flows to assist those species,” he said. “You have to mitigate for all the potential impacts, address where you place the sediment – again it’s an increasing challenge for both time and resources.”

At the Devil’s Gate Reservoir, the sediment has built up over multiple years, establishing some significant habitat and the community enjoyed using the area. However, following the Station Fire, a million yards of sediment came in and there was a need to remove that to restore flood protection. “It was a tremendous challenge working with regulatory agencies to address mitigation issues and how to make that reservoir function while still providing habitat and recreation opportunities,” Mr. Lilley said. “We’re now getting ready to remove sediment in the next month or so, ten years after the fire, to put it in perspective.”

These experiences highlight some concerns that as new stormwater infrastructure is developed, and especially with nature-based solutions, that they might be considered Waters of the US or Waters of the State or wetlands, he said.

“How we advance this new infrastructure and provide all these benefits but still be able to operate and maintain them in a cost-efficient manner so they can continue to provide new water conservation opportunities is of importance to everyone, I believe,” concluded Mr. Lilley.

FOR MORE INFORMATION …

- Click here for the Bureau of Reclamation’s Los Angeles Basin Study.

- Click here for LA County’s Safe Clean Water Program website.

DON BUNTS: San Juan Watershed Project

Don Bunts is Deputy General Manager for the Santa Margarita Water District, located in South Orange County. His presentation focused on the San Juan Watershed Project.

In South Orange County, there are nine water purveyors in the area. Currently, only 5% of their water supplies comes from local sources, about 15% is recycled water, and the remaining 80% is imported water. All the potable water at the Santa Margarita Water District is imported; about 25% of their water is recycled and put into a non-domestic system.

In South Orange County, there are nine water purveyors in the area. Currently, only 5% of their water supplies comes from local sources, about 15% is recycled water, and the remaining 80% is imported water. All the potable water at the Santa Margarita Water District is imported; about 25% of their water is recycled and put into a non-domestic system.

Water demand for the South Orange County area is roughly 104,000 acre-feet per year. Considering sustainability as well as reliability of imported water that could be affected by drought or earthquake, the Board of Directors is looking to increase locally sourced water supplies to 30%.

“We feel that’s a number that can be sustained to our customers so they would have indoor water use,” said Mr. Bunts. “In the event of an emergency, we would have to curtail all outdoor water use, but at 30% we feel we can sustain life and not have to have too many cutbacks on indoor uses.”

In the San Juan watershed, the groundwater basin is documented as an underground flowing stream, he said. “So not only are you trying to capture water in that basin, you’re trying to capture it before it runs out to the ocean,” he said. “We have stormwater runoff, and with climate change the flashiness of the storms has gotten worse. If we had been able to capture one of the larger storms that happened in February, the flow from that one storm would have taken care of South Orange County for the year, but unfortunately facilities aren’t there to be able to capture that volume of water in that time period.”

In the San Juan watershed, the groundwater basin is documented as an underground flowing stream, he said. “So not only are you trying to capture water in that basin, you’re trying to capture it before it runs out to the ocean,” he said. “We have stormwater runoff, and with climate change the flashiness of the storms has gotten worse. If we had been able to capture one of the larger storms that happened in February, the flow from that one storm would have taken care of South Orange County for the year, but unfortunately facilities aren’t there to be able to capture that volume of water in that time period.”

There is also 24,000 acre-feet of wastewater effluent that currently isn’t being recycled that they could capture and reuse within the region. And even though it’s an underground flowing stream, Mr. Bunts said they want to use the groundwater basin as a reservoir to store the water. “A number of projects have been done to do an adaptive management plan on that basin so that during drought years, you pull out less, and wet years you can pull out more. What we want to do is to be able to put in as much water as possible, regardless of whether it’s a wet or dry year.”

One of the challenges is that there are multiple agencies besides Santa Margarita Water District that operate in the watershed. There are a number of municipalities and a large unincorporated area; on top of that, there are multiple water districts with their jurisdictions. So they try to look at the watershed as a whole, figure out the best answer, and then figure out how to divvy up the water, duties, and costs between the different agencies.

“With the existing groundwater that’s being able to be extracted during wet years plus the combination of the three phases of this project, we feel like we can capture 17,000 acre-feet, plus or minus, which for us is roughly about 50,000 families,” said Mr. Bunts. “Our water district alone has 165,000 residences; coupled with the others, there’s somewhere in the vicinity of 400-450,000 people live in South Orange County.”

“With the existing groundwater that’s being able to be extracted during wet years plus the combination of the three phases of this project, we feel like we can capture 17,000 acre-feet, plus or minus, which for us is roughly about 50,000 families,” said Mr. Bunts. “Our water district alone has 165,000 residences; coupled with the others, there’s somewhere in the vicinity of 400-450,000 people live in South Orange County.”

Mr. Bunts said there are a lot of benefits to the project besides a local supply. “We also see that we’re improving the water quality because we’re going to be capturing some of the urban recovery waters that have a number of contaminants that aren’t necessarily good for the environment,” he said. “The creek runs across to the ocean. Doheney Beach is a huge tourist area, so from a financial standpoint, it helps the tourism business. There are ecological enhancements from backing that water up, the riparian habitat would not be suffering in the dry years, and then water storage that we can capitalize off and optimize the water that’s coming down the creek.”

Phase 1 will capture anywhere from 500 to 1400 acre-feet, depending on the rainfall. This phase of the project will utilize existing facilities. The city of San Juan Capistrano currently operates a brackish water desal unit by the creek right now because the water quality requires reverse osmosis. This phase of the project would be able to utilize those facilities because the plant is currently operating at about half capacity, he said.

Phase 1 will capture anywhere from 500 to 1400 acre-feet, depending on the rainfall. This phase of the project will utilize existing facilities. The city of San Juan Capistrano currently operates a brackish water desal unit by the creek right now because the water quality requires reverse osmosis. This phase of the project would be able to utilize those facilities because the plant is currently operating at about half capacity, he said.

The intention is to build three 7-foot diameter inflatable rubber dams along the creek to capture and filter the stormwater as it runs into the soil and infiltrates into the aquifer. Mr. Bunts said that the aquifer is shallow so it doesn’t take long to see the results. Right now, the phase one project cost is about $24 million. They started the EIR process in June of 2016, and they’re hoping to have it operational in 2021.

They currently operate two rubber dams right now. Coto de Caza is upstream of the dams, and when the community was constructed, it was designed to move stormwater out of the area quickly. “As we’ve gotten wiser and because of environmental restrictions, we are now trying to attenuate those flows so we did this project in conjunction with Orange County flood where a portion of this project stores floodwaters during the larger storms and then releases it over time to minimize what the damage is downstream and also to mitigate some of the new development in the area,” he said. “The upper portion of this captures the urban runoff, puts it through a wetlands treatment process and then it is reused in the non-domestic system that feeds the Coto de Caza area. Coupled with some recycled water that we were able to add to this because of this project, we reduced potable water use by 1250 acre-feet a year.”

Phase two involves the construction of more rubber dams, and also introducing recycled water behind the dams so they are able to maximize the infrastructure that’s been constructed. “Between the two desalters, we think there’s going to be enough capacity in those treatment plants to be able to handle it, so that’s helping keep the costs down,” said Mr. Bunts. “But one of the reasons the cost has gone up is because of the infrastructure with the recycled water. We’re able to utilize some existing pipe but we’ll have to build some new.”

Phase two involves the construction of more rubber dams, and also introducing recycled water behind the dams so they are able to maximize the infrastructure that’s been constructed. “Between the two desalters, we think there’s going to be enough capacity in those treatment plants to be able to handle it, so that’s helping keep the costs down,” said Mr. Bunts. “But one of the reasons the cost has gone up is because of the infrastructure with the recycled water. We’re able to utilize some existing pipe but we’ll have to build some new.”

Phase 3 is adding more recycled water during the dry periods into the natural channel. However, currently the Regional Board requirements don’t allow for livestream discharge in the San Diego region.

Phase 3 is adding more recycled water during the dry periods into the natural channel. However, currently the Regional Board requirements don’t allow for livestream discharge in the San Diego region.

“We have met with them and discussed it at length, and this is no longer going to be discharge permit but a recharge project,” he said. “Sometimes it’s just the semantics and changing the first three word to “re” can make a huge difference in how they look at this. As we have been developing this, we have been looking at going farther east out on this and utilizing some flood control basins that the developer is having to build. It’s high percolation rate and we’re looking at injecting even more recycled water out this creek to try and capture it.”

They are just about finished with the EIR for phase one, and they anticipate going to the Board of Directors for adoption at the May 17th board meeting. Pre-design efforts have been completed, but the final design is pending the outcome of the final EIR and the permitting process. They are hoping to start construction next summer.

He noted that when they started the project, they met with environmental groups and NGOs in the area, and got their input as they developed the project. “So far, we’ve received no resistance from any of the NGOs,” he said.

Permitting has been challenging. The creek has been identified as a steelhead trout, but one hasn’t been seen for at least 15 years, and not in any numbers for 40 to 60 years. “Part of the battle we’re faced with is the desire to return the creeks to a pristine environment whereas it’s a flood control element now, so we’re playing with the ups and downs that go with that,” Mr. Bunts said. “NOAA and NMFS have been the ones that we have been talking to the most, along with Cal Fish and Wildlife. The Regional Board seems to be accepting of it. We have not approached the Army Corps yet.”

Permitting has been challenging. The creek has been identified as a steelhead trout, but one hasn’t been seen for at least 15 years, and not in any numbers for 40 to 60 years. “Part of the battle we’re faced with is the desire to return the creeks to a pristine environment whereas it’s a flood control element now, so we’re playing with the ups and downs that go with that,” Mr. Bunts said. “NOAA and NMFS have been the ones that we have been talking to the most, along with Cal Fish and Wildlife. The Regional Board seems to be accepting of it. We have not approached the Army Corps yet.”

Funding is always a challenge. They have received grant funding from Metropolitan Water District, state agencies, and the Bureau of Reclamation. “One of the things that we still have to cross is the fish passages that appear to be required for this, to make sure that we encourage steelhead migration up the creek,” he said. “The downside is that for each of those dams, it’s about $1 million to $1.5 million to construct those fish passages.”

There are a number of benefits of the project, as far as water supply, water reliability enhancement, and providing some level of drought proofing. The key for selling it to the ratepayers was the utilization of existing facilities. “From a watershed standpoint with the MS-4 requirements, we’re trying to enlist some support from municipalities upstream, getting the Regional Board to understand and accept that there is treatment that’s taking place, and maybe modify the requirements that they have from upstream municipalities and also from CalTrans and the Orange County Transportation Authority,” he said.

There are a number of benefits of the project, as far as water supply, water reliability enhancement, and providing some level of drought proofing. The key for selling it to the ratepayers was the utilization of existing facilities. “From a watershed standpoint with the MS-4 requirements, we’re trying to enlist some support from municipalities upstream, getting the Regional Board to understand and accept that there is treatment that’s taking place, and maybe modify the requirements that they have from upstream municipalities and also from CalTrans and the Orange County Transportation Authority,” he said.

The project will also help stabilize the streambed and help with erosion issues, he concluded.

Commissioner Ball asked how long the rubber dams were inflated.

“What we’re proposing on the San Juan Creek project is they would basically be inflated until we see a ten-year storm or greater coming,” Mr. Bunts said. “Anything that might tend to want to overtop the berms of the existing channel, so we’re working with flood control to develop those numbers. It takes 20 minutes to deflate the dam, so if we see a storm that’s coming, it’s relatively easy to let that water down, but what we would like to do is capture the majority of the storms and especially the urban recovery, so that water is not running out across the beach.”

So they could be inflated for years at a time?, asked Commissioner Ball.

“Most likely not, because we usually get two or three storms that would be such that there would be a concern that it might overtop the berms and we don’t want to flood out any cities below,” Mr. Bunts said. “But it potentially could. It just depends on the rain events and the intensities that may come along with those.”

“The nice feature of the rubber dams is the sediment transport, because that material supplies the beaches downstream,” added Mr. Bunts. “Through the studies that we’ve done with the EIR, they found that the lower velocity storms, the lower intensities don’t carry that sediment down, so that even though we’re getting sediment buildup behind it, when the dam gets lowered with the bigger storms, that sediment can then move downstream and make sure it replenishes the beaches so we’re not starving them of sand in the future.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

- For the agenda, meeting materials, and webcast for the April meeting of the California Water Commission, click here.

- Click here to visit the State Water Board’s stormwater program online.

- Click here for the Pacific Institute Report, The Untapped Potential of California’s Water Supply

- Click here for the Pacific Institute Report, Sustainable Landscapes on Commercial and Industrial Properties in the Santa Ana River Watershed

- Click here for the Bureau of Reclamation’s Los Angeles Basin Study.

- Click here for LA County’s Safe Clean Water Program website.

- Click here to visit the San Juan Watershed Project website.

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!