Panel discussion looks at groundwater-surface water interactions under SGMA from a regulatory, environmental, academic, and policy perspective

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act defines sustainable groundwater management in terms of avoiding six undesirable results defined in the legislation: declining groundwater levels, reduction in groundwater storage, land subsidence, sea water intrusion, water quality degradation, and depletion of interconnected surface water. Of these six undesirable results, the one that has spurred the most discussion has been surface water depletions.

At the Groundwater Resources Association’s Western Groundwater Congress held this fall, a panel of speakers offered their perspectives on surface water-groundwater interactions under SGMA. Seated on the panel:

Regulatory perspective: Trevor Joseph, Supervising Engineering Geologist with Department of Water Resources. He has 20 years of combined consulting and state experience in water resources, specializing in planning, design, construction and oversight of various groundwater-related projects and programs.

Environmental perspective: Melissa Rohde, a groundwater scientist with the Nature Conservancy. She provides scientific leadership to the groundwater program to TNC’s California chapter using her expertise in biology, hydrology, and water policy to advance sustainable groundwater management.

Academic perspective: Dave Owen, a professor at UC Hastings, who teaches courses in environmental, natural resources, water, land use, and administrative law. His research has focused on water resource management, and the intersection of groundwater use regulation and the takings clause.

Policy perspective: Kevin DeLano, a geologist at the Division of Water Rights at the State Water Board, and his team is creating watershed models and engaging stakeholders to develop instream flow policy to restore endangered salmon runs on Coast Range watersheds throughout California; and Nicole Kuenzi, primary staff attorney with the State Water Board’s Groundwater Management Unit.

REGULATORY PERSPECTIVE: Trevor Joseph

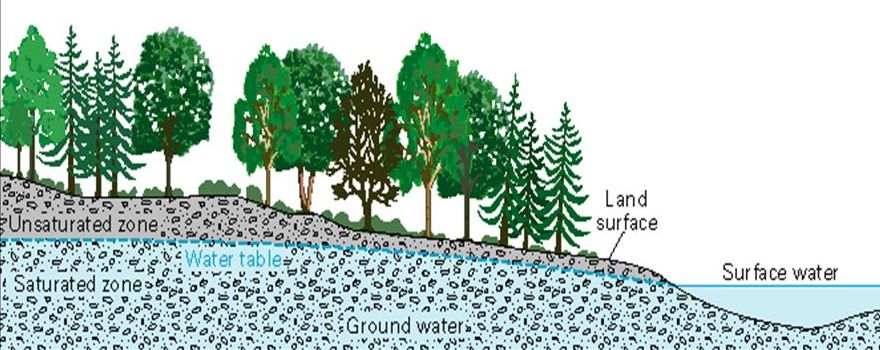

Trevor Joseph, Supervising Engineering Geologist with Department of Water Resources, noted that he is a hydrogeologist on a legal panel, so he will provide a context as it relates to surface water-groundwater interaction to set the stage for further discussion. The fundamental question here as it relates to SGMA is the surface and groundwater hydraulically connected? And that in itself poses some questions, he said.

He presented a rather complicated diagram which shows the many different factors and components involved with stream and aquifer interactions.

He presented a rather complicated diagram which shows the many different factors and components involved with stream and aquifer interactions.

The physical system has a number of factors to be considered. There are streams and surface water features that are connected, others that are disconnected, and those that are transitional, either in terms of seasonal variability or due to different flow requirements. Some receive water from imports or other sources. Also important are the actual properties of the aquifer, the sediments, the temporal and spatial scale, and the flow dynamics.

Data is another major component: there is the physical data, the stream geometry, the actual thickness of the stream bed, and the stream bed conductivity are incredibly important variables for understanding that timing of depletion. If you have clay-lined streams, they are not going to transmit as much water as if you have streams with boulders, cobbles, or gravels, so that streambed conductance and really understanding that data is key to understanding the timing of depletion, said Mr. Joseph.

Data on groundwater pumping is another important component for understanding the timing of depletion; also the distance wells are from surface water features, and the volume that’s pumped directly affects that timing.

There are a number of tools and methods for understanding of surface water depletion. “In a dynamic system like so many of the basins in the state, especially the Central Valley, it’s going to be really hard to do that without numerical approaches,” he said, noting that there are a series of surface water-groundwater models. “I’m not articulating that one is better than the other as they actually all use the same underlying governing equations to calculate surface-groundwater interaction. However, some are better than others based on the data and information that’s been used to input into those models.”

There are a number of different analytical or semi-analytical solutions. Some of these solutions are more applicable in basins that aren’t highly dynamic, such as those that aren’t adjacent to other basins. Other states have developed analytical methods such as Michigan and their surface well assessment tool.

With respect to SGMA, the water code is very clear that one of the undesirable results is the depletion of interconnected surface water that has a significant and unreasonable adverse impact on beneficial uses and users of the surface water. It is one of the sustainability indicators called out in the regulations, and if it’s applicable in the basin, it needs to be addressed in the basin’s Groundwater Sustainability Plan.

SGMA also has a clause that states that GSAs have some discretion to consider undesirable results that occurred before that date. “That’s very material to the discussion of surface-groundwater interaction because of the temporal nature of some of the depletions, or the transient nature of the depletions,” said Mr. Joseph. “Pumping years ago may still be having an effect on surface water throughout the state.”

The GSP regulations require the location, timing, and quantity of depletions if they are hydraulically connected. Next, sustainable management criteria have to be defined, and then monitoring is required. “Certainly you can leverage other programs and existing data, but those are really the three fundamental requirements related to surface-groundwater interactions in the regulations,” he said.

The GSP regulations require the location, timing, and quantity of depletions if they are hydraulically connected. Next, sustainable management criteria have to be defined, and then monitoring is required. “Certainly you can leverage other programs and existing data, but those are really the three fundamental requirements related to surface-groundwater interactions in the regulations,” he said.

GSAs have the obligation to consider beneficial uses and users, and that includes groundwater dependent ecosystems which are explicitly called out in the regulations as one of the beneficial uses that need to be described in the Groundwater Sustainability Plan. There are other regulations to be factored in depending on the area, such as minimum stream flow requirements, water quality, water rights, and other environmental requirements. Conjunctive management is important, and there are many programs such as Flood MAR and water transfers that are important for statewide sustainability.

Mr. Joseph then ran down the list of issues and questions.

How much depletion is acceptable? Since there really is no such thing as groundwater that didn’t originate at one point as surface water, the overarching question is how much depletion can occur without being significant and unreasonable. He acknowledged that depending on the location of the well and the type of hydrogeology, the impacts of groundwater pumping on surface water can occur within hours, days, weeks, or even years or decades, so how are transient effects of pumping going to be handled in these Groundwater Sustainability Plans, especially related to the January 1, 2015 date?

The quality and accuracy of modeling results will be a question. “There is uncertainty, no question, in the modeling results,” he said. “Garbage in is garbage out in some models, yet it’s the best tool that we have. A lot of the models have become more refined so that we can get a fairly accurate representation of the surface water depletions, but there’s always that uncertainty and that uncertainty is okay.”

Delta conditions are relevant to groundwater substitution transfers, because depending upon whether the Delta is in balance or excess conditions, there could be impacts or legal injury associated with those depletions. Adjacent basins and GSAs will be challenged with figuring out how to address depletions when the surface water feature flows across multiple basins.

The Environmental Defense Fund has put developed an approach for using groundwater levels as a proxy. “It is an option to use water levels as opposed to the rate and volume to define a threshold for determining what sustainability is in the basin, and EDF has gone to a great effort to explain how that possibly could be done,” Mr. Joseph said. “It depends on the beneficial uses of that surface water, and in some cases, that may not be enough. That has yet to be played out.”

Finally, there are overlapping regulations. Will the GSA’s minimum streamflow be enough, he said.

“I hate to leave you with a lot of questions, because I know we’re the state and we’re going to be looking at these plans and GSAs are asking what’s going to be acceptable, but what we’re focused on here is not perfection in these plans,” Mr. Joseph said. “These plans need to be complete, they need to address the requirements, but we’re not anticipating that all plans, day 1, are going to solve all issues related to this topic. This is going to be a journey.”

“I hope we can evolve and see progress being made over time in terms of testing these outcomes, because the regulations are outcome based, in terms of what’s working and what’s not working as it relates to defining significant and unreasonable undesirable results related to surface-groundwater interaction,” he concluded.

Moderator Jena Shoaf Acos notes that there are requirements for measuring and making sure there are no significant and undesirable results from surface water groundwater interactions, but can you speak to how DWR, as the reviewer of these plans, is going to be taking into account that significant and unreasonable standard? Do you have pointers for local agencies about what that means – Is anything unreasonable? Is anything significant?

“I’ll go back to hydrologically connected as that’s important,” said Mr. Joseph. “The statute says interconnected systems, but there are basins where there isn’t a connection. I don’t think that it’s a GSAs obligation to reconnect those surface water features unless they feel they need to, based on what’s in the law.”

“Defining what’s significant and unreasonable is local controlled so you have to work through those beneficial users to determine what is that balance,” he continued. “The Department really doesn’t have a cheat sheet on what is significant and unreasonable in all of these basins. We don’t know the basins as well as the local agencies do and the stakeholders. We’re really focused on whether you followed the process, did you define things scientifically, and did you quantify what sustainability means. Other stakeholders, such as the State Board or others, may weigh into that such as other local agencies, the environmental folks, and ag interests. Really that’s a balancing act that we recognize is really tough, but it’s on the GSAs. We’re not looking to opine on what is significant and unreasonable. We don’t feel that it’s our role.”

ENVIRONMENTAL PERSPECTIVE: Melissa Rohde

Melissa Rohde, groundwater scientist with the Nature Conservancy, began by saying she was an East Coast transplant who came to California and instantly fell in love with the diversity of the landscape – the redwood forests, the coastal wetlands, the mountain springs, the rivers and the amazing food in the grocery store.

“We are very privileged to live in California, and it’s really important to realize though that for the past century, we’ve lost a significant portion of the native wetlands and river habitats that existed in the state, for multiple reasons, not just because of groundwater pumping, but groundwater depletion has contributed to it,” she said. “I’m not saying that SGMA requires to take us back to pre-settlement conditions, but what I am trying to say here is what’s left is a really small fraction of what we had, and I think we have a civic duty to protect it for future generations.”

“We are very privileged to live in California, and it’s really important to realize though that for the past century, we’ve lost a significant portion of the native wetlands and river habitats that existed in the state, for multiple reasons, not just because of groundwater pumping, but groundwater depletion has contributed to it,” she said. “I’m not saying that SGMA requires to take us back to pre-settlement conditions, but what I am trying to say here is what’s left is a really small fraction of what we had, and I think we have a civic duty to protect it for future generations.”

Ms.Rohde stressed that we need to be cognizant that the fraction that we’re dealing with is fragile and in a vulnerable state. “So when we’re at our computers and circling areas and looking at these huge basins, we can easily lose touch with what we’re talking about, and so just remember that this is what we’re talking about.”

SGMA is about a stakeholder process and GSAs have the obligation to protect the interests of all beneficial uses and users. “They are supposed to be a neutral party that balances these beneficial uses and users, and groundwater dependent ecosystems are a type of beneficial use or user, and they need consideration,” she said. “They are specifically called out in the Act.”

“There are these six undesirable results, and of the six, groundwater dependent ecosystems are most relevant to lowering groundwater levels, degraded water quality, and surface water depletions,” she said. “The legislation also calls out for protecting beneficial uses of surface water under the undesirable result #6, so from an environmental perspective, this is instream habitat that my exist in losing reaches or not directly using groundwater but using surface water.”

There are a lot of beneficial uses and users, but they are not created equal; some beneficial uses have more of a voice than others, and some have more legal protection than others. “So in the case of interconnected surface water, we need to maximize the beneficial uses while minimizing legal risks. So it’s a balancing act. How do we do that?”

There are a number of things to take into account, such as the legal risks, the core values that each local GSA area will have, and the different economic benefits. Ms. Rohde said that one of the challenges will be that if groundwater levels are used as a threshold along the rivers, GSAs will need to know what’s inside the river that is benefitting from that.

One way to do that is to determine what the thresholds are for each of the beneficial uses and users, she said. For example, for domestic or ag wells, the threshold could be the bottom of screen depth interval, or for infrastructure, it could be holding capacity. For groundwater dependent ecosystems, it could be the specific groundwater levels near the stream that are necessary to keep roots of plants having access to groundwater or other discharges from groundwater and surface water systems.

The Nature Conservancy has developed a guidance document which discusses the technical aspects of determining that. They also worked in partnership with the Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Department of Water Resources to put together the Natural Communities Commonly Associated with Groundwater dataset which will help determine where the environmental beneficial uses and users of groundwater exist in your basin.

There are currently statewide flow criteria being developed for instream habitat by the Nature Conservancy, UC Davis, UC Berkeley, the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project, and the USGS. “The hope is that we can use this to better understand how much water needs to be left in the river, and maybe what groundwater levels are necessary to maintain those minimum instream flow criteria,” Ms. Rohde said.

After determining the hydrologic requirements for each of these beneficial uses and users, it’s then important to figure out which of the beneficial uses and users have other legal protections. “That’s part of your legal risk assessment,” Ms. Rohde said. “Then you need to do an evaluation of what the tradeoffs are – what are the economic tradeoffs, what are the legal risks, and what are the core values that exist in your basin so that you maximize the beneficial uses.”

She presented a figure taken from a paper that was about achieving environmental benefits in South Africa. “There’s a point where you can maximize beneficial use,” she said. “Not everyone always wins, but there’s a sweet spot that we need to find. I think it’s possible to come up with some kind of framework to do this.”

She presented a figure taken from a paper that was about achieving environmental benefits in South Africa. “There’s a point where you can maximize beneficial use,” she said. “Not everyone always wins, but there’s a sweet spot that we need to find. I think it’s possible to come up with some kind of framework to do this.”

There’s been a lot of discussion about what is significant and unreasonable, but it’s important to be specific, because the more specific you are, the more likely you will get there, she said.

“You can’t know what is significant and unreasonable until you know what is needed instream,” she said, presenting a figure from the Santa Cruz Mid County Groundwater Sustainability Agency. “They have essentially mapped out where all the listed species are in their basin. I thought this was a really interesting approach because if you know that a certain species needs a certain flow criteria in a specific part of your basin, you can figure out what groundwater levels would be necessary to maintain that. And I know that there’s the January 1, 2015 date to consider, but in this case, Santa Cruz Mid County has put in their sustainability goal that they want to address pre-2015 issues.”

“You can’t know what is significant and unreasonable until you know what is needed instream,” she said, presenting a figure from the Santa Cruz Mid County Groundwater Sustainability Agency. “They have essentially mapped out where all the listed species are in their basin. I thought this was a really interesting approach because if you know that a certain species needs a certain flow criteria in a specific part of your basin, you can figure out what groundwater levels would be necessary to maintain that. And I know that there’s the January 1, 2015 date to consider, but in this case, Santa Cruz Mid County has put in their sustainability goal that they want to address pre-2015 issues.”

“I’m not trying to say that we should be managing our basins for individual species,” she continued, “but when we’re trying to figure out what would be significant and unreasonable in these early days, it’s important to figure out what does that mean and what would we need to do to prevent that. Are our groundwater levels sufficient right now to protect it, and if not, are there projects we can put in place in order to recover those conditions, if locals want that.”

Ms. Rohde noted that on the left of the slide is a statement that could be used to be explicit about when a significant and unreasonable effect would be happening. She pointed out that a similar formulaic statement like this could be developed for other beneficial uses and users.

To aid GSAs, they have compiled a list of threatened and listed species per basin and emailed that to each of the GSAs. “I would encourage that folks map where these things are so it makes it a little bit more concrete when we’re talking about what’s significant and unreasonable,” she said.

Ms. Rohde said she is currently leading a project that’s an interagency collaboration between NOAA, US FWS, DFW, and Audubon to compile existing information about hydrologic thresholds for different listed species. “Quite commonly in these meetings, environmental representatives and resource agencies are asked, what flow criteria do we need in the stream? A lot of times, that catches us by surprise because it’s so complicated, but I think we can compile the best information on this topic. Then we’ll communicate that to the GSAs and also to the resource agencies that are already monitoring these species, so we can identify where are the knowledge gaps and what information needs to be collected in order to bring more clarity on what is actually required.”

Audience question: My question is a biological ethical one. Who do you give the last drop of water to – the non-native fish or the native pollinator in a groundwater dependent ecosystem. Which is more important? Is it all about the riparian habitat? Is it all about native species or non-native species? I’m very much into sustainability and the environment … for me a lot of native species or non-native species can co-exist with agriculture. How do you balance the biological ethic?

“This is the danger with playing God a little bit in managing each individual species,” responded Ms. Rohde. “It’s really important to think about the ecosystem health as a whole, and there’s a lot of research out there trying to define what that means. How do you know an ecosystem is healthy? So when we did the mapping exercise with DWR and DFW, we had to rely on statewide available datasets to do this for the whole state. Plants, particularly pteridophytes, are really a great indicator species because they provide essentially the ecosystem structure. Research has shown that when you have a rich vegetation ecosystem, and you have a lots of different levels, you have many different birds and mammals that can inhabit that ecosystem, so if you know that your vegetation is healthy, then it’s a pretty good indicator that everything else is doing well – with the exception of if there are endangered species that need specific monitoring.”

“But realistically, SGMA is being implemented by hydrologists, geologists, and engineers, and biology is not really a specialty,” she continued. “Surveying these very specific organisms can be time consuming and difficult to interpret. However, vegetation is a good indicator because you can monitor it from satellites or through aerial photography, so we tend to promote it as a good indicator. We are currently doing satellite research looking at the LANDSAT record to see if there are impacts that we can see due to groundwater depletion. Our hope is that we can use that satellite imagery in order monitor these ecosystems at least in an initial way. More investigation is needed; depending on the legal risk and how important it is, then more investigation can be done.”

Moderator Ms. Acos notes that GSAs and their counsels should look at the Nature Conservancy’s guidance for addressing GDEs under SGMA. “It’s an excellent document, in addition to just looking at the website. I think avoiding undesirable impacts is not going to be a check the box exercise; it will take some significant and additional analysis on the part of the GSAs to achieve that.”

“We can’t do everything in this round of GSPs,” said Ms. Rohde. “From my perspective, we just need to know where these ecosystems are in areas of importance, and then make sure that we have enough monitoring in place to see what these cause and effects are. Good hydraulic monitoring in and around these GDEs is needed. It’s quite common that there aren’t sufficient shallow monitoring wells in and around these areas, so it’s really hard to figure out what groundwater levels would be necessary to maintain that ecosystem, so filling that knowledge gap is something we’re going to be looking at closely. We also need to collect some biological information. You won’t know if you’re having an impact if you’re not looking at what the impact is. How do you know that you’re causing a significant undesirable result if you’re not looking at what the impacts could be, and we provide guidance on that. You could go crazy and do a lot of research, but we tried to keep in mind the feasibility aspect of this whole process, so in our guidance document, we have some tips on how to do that, cost and time effectively.”

ACADEMIC PERSPECTIVE: Dave Owen

Dave Owen, a professor at UC Hastings, next gave a perspective from the field, noting that he will be sourcing his remarks from a series of workshops hosted by some colleagues at UC Berkeley and UC Davis which included groundwater experts, agency officials, NGOs, local GSAs, attorneys and consultants. The workshop discussed cutting-edge and challenging SGMA-related issues at the intersection of groundwater and surface water, with the discussion primarily turning to legal issues.

One issue they kept coming back to was the theme that SGMA is more of an overlay or an addition on a pre-existing body of law that deals with groundwater-surface water interactions, although not always effectively. That body of law is still there post-SGMA, so SGMA is not one-stop shopping for the legal obligations that pertain to groundwater and surface water.

A second and closely related conclusion was that a lot of the most challenging issues are going to be at the intersection of groundwater sustainability planning and other laws. SGMA obviously creates some challenging issues, like figuring out what is a significant and unreasonable impact, but that’s just one of many challenges that GSAs, groundwater users, and surface water users are going to confront, he said.

The third takeaway was that even though SGMA doesn’t provide one-stop shopping for the legal obligations, it can provide something fairly close to it for process. “In other words, you can use this groundwater sustainability planning process, not just to resolve the issues that SGMA raises, but also to deal with a number of other issues,” he said.

Mr. Owen then elaborated on these points.

First, SGMA isn’t one stop-shopping for legal requirements as there are a number of others that also going to matter and will be important. One example is groundwater and surface water rights. SGMA expressly disclaims making any change to groundwater and surface water rights; it doesn’t purport to be a statute that’s going to decide what those rights are or how they interact with each other.

First, SGMA isn’t one stop-shopping for legal requirements as there are a number of others that also going to matter and will be important. One example is groundwater and surface water rights. SGMA expressly disclaims making any change to groundwater and surface water rights; it doesn’t purport to be a statute that’s going to decide what those rights are or how they interact with each other.

“The on-the-ground reality is that because groundwater and surface water are connected, the things we do to manage groundwater are going to have impacts on the ability of surface water users to exercise their rights, and if we try to protect surface water flows for the sake of protecting surface water users, that means limiting groundwater pumping,” he said. “There are going to be disputes that may get wrapped up in the groundwater sustainability planning process about how to resolve the relative claims, particularly those of surface water appropriators and overlying groundwater users, each of which can look at the definition of their own right and claim a trump card over the other. Sorting out these particular conflicts is not a mandate of SGMA, but as a practical matter, these are issues that groundwater managers are probably going to have to deal with.”

The takings doctrine is another legal issue that GSAs may have to contend with. Both the constitutions of the United States and of California protect property rights from being taken by government without just compensation. Water rights in California are property rights and that’s a well-settled area of law, and so they are protected by the takings clause.

“While SGMA disclaims any effect on water rights, the reality is that GSAs, through their GSPs, are going to be limiting pumping in at least some circumstances, or in other words, they are going to limit the ability of people to pump water under a claimed property right,” he said. “Similarly, where GSAs decide to be relatively permissive with groundwater pumping and to deplete surface water flows to a greater extent, that’s going to limit the ability of people to exercise surface water property rights, and so it’s at least probable that GSAs are sometimes going to be hit with takings claims with arguments that their decisions have taken property rights.”

“Fortunately, here GSAs are somewhat protected by the general California legal principle that all water rights are subject to reasonable regulation, and it is embedded in the right itself, that general susceptibility to regulation, and that should provide GSAs with at least some protection from takings claims,” Mr. Owen said. “But I suspect they will be coming. Maybe not tons of them, but there will be at least some.”

Under the California Constitution, all water is subject to the reasonable use doctrine and so unreasonable uses of water are not allowed. That doctrine has long been held to extend to groundwater as well as to surface water, he said. “SGMA doesn’t say anything specific about what is or is not a reasonable use of water; it doesn’t explicitly lay out a process for making these reasonable use determinations; yet, the water users that are subject to SGMA need to use their water reasonably, and the local GSAs and DWR and the State Board are also going to need to take reasonable use into account as they make their decisions about how water should be allocated.”

This will be a somewhat unfamiliar position for agencies to be in as they aren’t accustomed to making these decisions, and tend to think of the State Board and the courts as the primary arbiter of the reasonable use doctrine. “But in general, if you’re a government agency, you don’t want to go into to court saying, ‘it’s our understanding that the constitution is for somebody else to worry about’ – that’s not a readily defensible position. And so again, figuring out what counts as a reasonable use is likely to be a piece, at least sometimes, of the groundwater sustainability planning process.”

The public trust doctrine could also come into play. A recent California Court of Appeals decision in the Scott River litigation held that groundwater that flows into surface waterways is protected by or is subject to the public trust doctrine, so long as those surface waterways are public trust waterways. The decision has been appealed to the California Supreme Court, and Mr. Owen said his prediction is the Supreme Court won’t take it and if it does, it will uphold the Court of Appeal which in turn, upheld the trial court in this case.

The public trust doctrine could also come into play. A recent California Court of Appeals decision in the Scott River litigation held that groundwater that flows into surface waterways is protected by or is subject to the public trust doctrine, so long as those surface waterways are public trust waterways. The decision has been appealed to the California Supreme Court, and Mr. Owen said his prediction is the Supreme Court won’t take it and if it does, it will uphold the Court of Appeal which in turn, upheld the trial court in this case.

“I think this is the law going forward, and that means that groundwater management decisions by public agencies are subject to the public trust doctrine,” he said. “More specifically, that means there is an obligation to consider impacts on public trust resources when making decisions involving groundwater management, and while there is not an obligation to protect public trust resources above all else, or in other words, the public trust doctrine is not an environmental trump card, there is an obligation to protect those resources when it is feasible to do so.”

Mr. Owen said that the recent court decision regarding the public trust doctrine and groundwater will bring about modest changes in groundwater management, but likely won’t bring about major changes, pointing to the fact that the same doctrines have applied to surface water management since the Mono Lake decision over 30 years ago, and there is very little historical evidence that the public trust doctrine has had a transformative effect for California surface water management.

“However, the recent experience with the State Board’s efforts to use the public trust doctrine to bolster inflows on Delta surface water tributaries is a reminder is that if state agencies or local agencies want to beef up environmental protection of surface flows, the public trust doctrine gives them a powerful basis for doing so,” he said. “Historically, that inclination has not been there very often but it could be going forward, and so for a GSA that really wants to include strong surface water protections in its plan, there is now a more clear legal basis – one of many, but another legal basis for doing that.”

There are also a lot of federal and state environmental protection statutes that pertain to surface water management, and therefore could have at least some potential impact on groundwater and surface water interactions, Mr. Owen said, but with respect to groundwater and surface water interactions, the most important law is the Endangered Species Act. The federal Endangered Species Act has been very influential for surface water management in much of California, but he didn’t think it will be as influential for groundwater management. Section 7 is the most influential part of the federal Endangered Species Act, and it requires federal agencies to avoid jeopardizing listed species or adversely modifying their critical habitat; however, section 7 doesn’t apply to state or to local agencies which are the agencies doing nearly all of the groundwater management, so therefore they are simply not subject to it at all. The California Endangered Species Act has no similar language.

However, Section 9 of the Endangered Species Act does apply to state and local government as well as private actors, and it inhibits what are called ‘takes’ of endangered species, which is essentially killing or harming members of the species. Section 9 could potentially apply to groundwater managers and users and also potentially to GSAs, but Mr. Owen said there are a couple of reasons why he thinks there won’t be a lot of Section 9 litigation against GSAs.

“One is that there is some uncertainty and some disagreement in the courts about when a regulator can have take liability because of its regulatory program,” he said. “It really depends on whether you construe the regulatory program as giving permission for activities to occur, in which case then we might give the permitting agency or the agency authorizing activities take liability, or if you construe it as a restraint. And in that circumstance, you would say, well they are restraining harmful behavior and you can’t sue them under section 9 for not restraining it even more, that’s the responsibility of the actual actors. So there’s a bit of a court split on that question.”

“Additionally, in order to impose take liability on even an individual groundwater actor, you have to make what is sometimes a fairly difficult showing of causation,” he continued. “You have to link negative impacts on discreet members of the species to that particular groundwater user’s pumping, and that particularly in a complex aquifer with a lot of pumpers can be a very difficult showing to make, even if we are perfectly well aware that in the aggregate, groundwater pumping has major effects on protected species.”

The main point here is that there are a lot of different legal doctrines going beyond SGMA itself, and they still have importance for groundwater and surface water interactions, and it could at least come up in the groundwater sustainability planning process, he said.

Although SGMA itself is not one-stop shopping for finding legal requirements that pertain to groundwater surface water interactions, it does provide a way and a clear process where a lot of these different interests and questions could be resolved at once, he pointed out. “In other words, in the GSP planning process, you can take it as just an opportunity to comply with SGMA and that’s it, but it can also be treated as an opportunity to figure out what flows are needed to sustain endangered species, and how you are going to resolve conflicts between groundwater and surface water right holders. That means bringing a lot more stakeholders and a lot more issues into the room, which means more time and money, but there may be some advantages there as well.”

Mr. Owen then gave an example from the Russian River Valley about how an inclusive process can actually be advantageous. In the upper part of the valley, there was a number of small primarily groundwater-supplied agricultural basins with relatively small agencies managing them, and in the lower part of the Valley, there is the Sonoma County Water Agency, a relatively big and well funded agency with a pretty high level of expertise to draw upon.

“The Sonoma County Water Agency was very happy to contribute some of its funding and some of its expertise to the planning, because it saw a benefit to itself in protecting surface water flows and achieving better management of those,” he said. “We had this symbiotic relationship that was beginning to unfold at the time we were doing the work where there was an advantage to both the big surface water agency and the smaller groundwater ones of working together and broadening the scope of issues they resolve, and that sort of arrangement where you broaden the scope of the planning but you also bring in more planning and more expertise and potentially more funding, I think could be replicable and is worth pursuing in other places as well.”

Question: What your thoughts are on water rights priorities and whether or not a groundwater pumping that is injuring surface water rights ought to be or is under the law of a per se unreasonable effect that GSAs will have to consider?

“I don’t think that can be a per se unreasonable impact, because if it was, most of the groundwater pumping in California would be per se unreasonable because most groundwater pumping in California is drawing from aquifers that at least at some point in the past, depleted surface water,” said Mr. Owen. “Now we have the pre-2015 cutoff, but even then, I think it’s just hard to say that all groundwater use that additionally depletes a competing surface water use is per se unreasonable because that would create an absolute priority for surface water use in California. I think if the legislature wanted to try and do that, it could, and certainly other states have done things like cutting off riparian rights in some circumstances and other states have abolished them. But it seems to me that the better answer is to use reasonable use doctrine to try and set common metrics across groundwater and surface water use for what counts as reasonable use, taking into account things such as efficiency, the economic return on the use, and environmental impacts. If you could create metrics that basically treat groundwater and surface water equally across systems, I think that is a fairer way of trying to resolve the two systems.”

He then gave two scenarios that illustrated the water rights questions involved. One scenario is where groundwater users have been pumping and using water for longer than the surface water users at current levels. “By the internal logic of the surface water allocation system, assuming that they are appropriative water rights users, if you have essentially a senior groundwater user and a junior surface water user, than I think that groundwater user has a very powerful argument that his or her use trumps the surface water user,” he said.

“The hard question is when you have an appropriative surface water who came first, and a groundwater user who bought the land before the surface water user started pumping, but didn’t start pumping water until later. By the logic of groundwater rights, that is an overlying user who has a right based on landownership, so that date of that right within the internal groundwater system would be based on the date of purchase. By the logic of the surface water system, the surface water user would say, ‘your right is not senior because I started using water first,’ and in prior appropriation, what matters is coming first. So we basically have a clash of two different and sometimes irreconcilable principals for allocating water. The best way out of that that I can see is to use something that is common to both systems to figure out the standard and that’s reasonable use.”

Question: The regulations require that the GSAs through GSPs to discuss if their minimum thresholds differ from existing state or federal regs or laws and why. Can you shed any light on when or how that might be defensible? If they are setting surface water depletions to be less than instream flow requirements, are there cases where you could see minimum thresholds differing from state and federal laws and standards as a defensible approach?

Mr. Owen said that he thinks that is a very likely scenario. “There may be times when a GSA decides to set pumping levels at a certain level and the National Marine Fisheries Service might say that they think it isn’t going to be enough water left in the stream for steelhead trout at that pumping level, and the GSA might say, ‘That’s your problem. Our obligation is to comply with SGMA. Show us the part of the Endangered Species Act that tells us that we are subject to some obligation here.’ So I think that is a likely conflict, and I think a claim that environmental groups will say that when you are setting your reasonable levels, you have to take into account flows that are necessary to protect listed species, that seems to me like a pretty strong argument.”

“Another thing to make it even more complicated is that there may be real uncertainty; you may not have NMFS weighing in and saying what flows are necessary, but I think you’re going to have situations where there are big evidentiary gaps and it’s hard to figure out what actually is consistent with those other obligations,” Mr. Owens continued. “Then you’re also going to have legal gaps where the GSA is basically saying, ‘we’re not inconsistent with any state or federal law, because the relevant law that you’re talking about creates obligations for other people, not for us.’ I’m not entirely sure how that case would come out.”

Question: If the NMFS has provided comments on a Groundwater Sustainability Plan, does DWR pause the GSP if the GSA chooses not to take those comments into consideration? or is DWR essentially passing the buck to environmental stakeholders to keep doing this litigation game?

“I think under the reasonable use doctrine, public trust doctrine, and elements of SGMA, DWR is at least obliged to take those comments into account and come up with a credible and reasonable response to them,” said Mr. Owen. “I don’t think NMFS has the ability to come in and mandate an instream flow level for a GSP because its authority is limited to implementing Section 7 and Section 9 of the Endangered Species Act. If it’s really upset with what’s done, it could potentially initiate a Section 9 action although it’s not clear who the defendant would be. So from DWR’s perspective, those are the requested flows of an expert agency; they are not a legal mandate, but they could turn into a legal mandate through the operation of other legal doctrines.”

POLICY PERSPECTIVE: Kevin DeLano and Nicole Keunzi

Nicole Kuenzi, Staff Counsel with the Office of Chief Counsel at the State Water Board and Kevin DeLano, Geologist with the Instream Flow Unit, Division of Water Rights at the State Water Board then gave the final presentation.

Kevin Delano began by saying that there has been much discussion about surface water rights, GSAs, SGMA and endangered species colliding with each other, and one of the places that this is occurring is in the Ventura River watershed where the State Water Board and the Department of Fish and Wildlife are developing an instream flow policy that may lead to an instream flow requirement.

Before SGMA was passed, the administration put forth the California Water Action Plan which directed the State Water Board and California Department of Fish and Wildlife to work together to enhance instream flows for endangered salmon on watersheds throughout California that are beyond the Bay Delta. As part of that, the State Water Board and the Department of Fish and Wildlife have been focusing on coastal range rivers, looking at four watersheds, one of them being Ventura.

The Ventura River and Southern California are still in drought; they never really came out of drought. The main water supply reservoir on the Ventura River is at about 30-40% capacity. At times, the Ventura River has poor water quality and can be covered in algae; reaches that would historically flow all year around have been going dry in the last few years.

Nicole Kuenzi, Staff Counsel with the Office of Chief Counsel at the State Water Board, added some comments, after first giving the standard disclaimer that her comments are entirely her own and not necessarily those of the State Water Board. She said that she sees the role of State Board in SGMA implementation as actually being much less about the authorities granted under SGMA and more about how the State Board’s other authorities could be rolled in by GSAs in their efforts to implement SGMA.

“SGMA is a process or a venue for bringing up some of these other issues and playing out some of the State Board’s other authorities,” she said. “Kevin and I both want to stress that throughout this, the Board is looking for ways to be helpful and for mechanisms that are voluntary, that are cooperative, and ways that the State Board can exercise its authorities in manners that will help GSAs implement their GSPs and help achieve sustainability in the basin.”

Ms. Keunzi said that the State Board’s authorities could be categorized into two types: regulatory or enforcement authorities and voluntary or enabling authorities.

Ms. Keunzi said that the State Board’s authorities could be categorized into two types: regulatory or enforcement authorities and voluntary or enabling authorities.

With respect to regulatory and enforcement authorities, she noted that the Board does not have permitting authority over groundwater except for subterranean streams and the Russian River, which is its own special place.

However, the board has other tools that can be used to address the interaction between groundwater and surface water, most notably the waste and unreasonable use doctrine and the public trust doctrine. Historically, she noted that those doctrines been implemented in rare cases, one of those being the Russian River frost regulations (which incorporated groundwater pumping to the extent that those impacted surface water flows) in limiting pumping under the Board’s public trust and waste and unreasonable use authority as the pumping for frost control would essentially dewater the Russian River. Another example was during the drought where there were certain regulations on specific stream segments that had to do with the dewatering for protection of salmon and other species, and those also applied to groundwater users, even though the Board’s permitting authority doesn’t extend to groundwater.

Ms. Kuenzi also noted that the Board is charged with a administering the water rights priority system with respect to surface water that is within the Board’s permitting authority, but it may be possible that the Board may be able to implement its waste and unreasonable use authority in some instances to address cases where there is either pumping or surface water diversions out of priority. “That is a legal issue that just hasn’t been addressed,” she said. “I think that as everyone is tightening their belts with SGMA and SGMA implementation, it’s going to bring forward some of these interesting legal issues about the extent of the Board’s authority.”

In the second category of tools, the voluntary or cooperative efforts, the board has an informational and data gathering role and this type of investigatory role can be very helpful for GSAs. “We hope that the GSAs in the Ventura can coordinate with the State Board and build upon the work that’s being done and the money that is being spent to develop models so that we can all use these shared models, which is cost effective as well as helps avoid combat science when everyone agrees on a model.”

A second important authority that Ms. Keunzi said was likely to be coming up more is the Board’s authority under Water Code Section 1707, which authorizes the Board to permit any kind of water right – not just surface water rights or permitted water rights, but any kind of water right can be transferred to enhance instream flows to meet either instream flow standards or essentially float on top of whatever instream flow standards may apply in the watershed section, she said.

“We’re investigating currently whether this tool can be used in the Ventura River basin and the watershed to transfer groundwater rights that are very closely interconnected with surface water, so that voluntarily, pumpers can essentially park their water rights, agree to stop pumping and protect that share of the water that is instream, and then enter into these voluntary arrangements,” she said. “As I understand, there are grant programs that can help to fund these types of arrangements, so I think this is potentially a very appealing avenue to meet instream flow standards without an exercise of regulatory authority through cooperative and voluntary mechanisms.”

Another important authority of the State Water Board that relates to SGMA is that surface water in many basins is going to be put underground intentionally to enhance groundwater levels. “That surface water is often subject to the Board’s permitting authority so it will be very important for the Board and GSAs to work together cooperatively as to how to permit those projects,” said Ms. Keunzi. “Surface water stored underground is subject to the Board’s authority and the Board’s regulations through its permits, so the Board has been working on efforts to streamline issuance of certain types of permits for high flows to underground storage, and then also brainstorming ways that our permits can be integrated with GSPs.”

She concluded by stressing that the Board is definitely interested in cooperative and voluntary solutions. “This is all going to be a belt tightening exercise under SGMA and so it’s important to explore these other mechanisms to distribute the burdens of meeting instream flow requirements.”

Kevin DeLano then discussed the Ventura River study, beginning by presenting a map of the watershed, which is located between Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. The northern part of the watershed is steep, rugged mountains with peaks up to 7000 feet and flash floods that bring a lot of sediment load down from the mountains. There can be 20 to 40” of precipitation up in the mountains yet only 15” down at the coast, so the rivers can really ignite, he said. The rivers flow out of the mountains and on to the valley floors. He noted that the Department of Fish and Wildlife are also simultaneously working on an instream flow study to determine what flows are necessary to protect endangered steelhead.

Kevin DeLano then discussed the Ventura River study, beginning by presenting a map of the watershed, which is located between Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. The northern part of the watershed is steep, rugged mountains with peaks up to 7000 feet and flash floods that bring a lot of sediment load down from the mountains. There can be 20 to 40” of precipitation up in the mountains yet only 15” down at the coast, so the rivers can really ignite, he said. The rivers flow out of the mountains and on to the valley floors. He noted that the Department of Fish and Wildlife are also simultaneously working on an instream flow study to determine what flows are necessary to protect endangered steelhead.

There are four SGMA recognized groundwater basins; two of them are medium priority basins that have a management agency in place and two are low priority and are not subject to SGMA at this time. There are numerous groundwater wells in the region that are used for agricultural, domestic, and municipal use. Northeast of the upper Ventura Basin is the Ojai basin, which had an existing Groundwater Management Agency that preexisted before SGMA and now has taken over as the GSA. There are also senior water rights in the watershed.

There are four SGMA recognized groundwater basins; two of them are medium priority basins that have a management agency in place and two are low priority and are not subject to SGMA at this time. There are numerous groundwater wells in the region that are used for agricultural, domestic, and municipal use. Northeast of the upper Ventura Basin is the Ojai basin, which had an existing Groundwater Management Agency that preexisted before SGMA and now has taken over as the GSA. There are also senior water rights in the watershed.

When the headwaters tributaries of the Ventura River exit the canyons, they flow onto open valley floors and the up to a certain point, the surface flow just sinks right into the aquifer; there is a reach of the river that even before there was much settlement in the watershed, that reach would still go dry during the dry season. Farther downstream, there’s a zone where groundwater upwells and downwells in this watershed and it shifts, upstream and downstream, depending upon how much water is in storage in the aquifer and how much water is coming in from the rainstorms, he said.

The Department of Fish and Wildlife has been walking the river with GPSs and tracking where groundwater is upwelling and downwelling to collect data to be used in the surface water-groundwater model of the Ventura River watershed that is being developed.

The Department of Fish and Wildlife has been walking the river with GPSs and tracking where groundwater is upwelling and downwelling to collect data to be used in the surface water-groundwater model of the Ventura River watershed that is being developed.

“This is a watershed where there are probably groundwater dependent ecosystems, and so that’s what Fish and Wildlife is trying to find out, how much streamflow is needed in some of these streams that depend on groundwater upwelling to provide streamflow,” Mr. DeLano said. “We’re making a surface water groundwater model of this watershed and we’re trying to do it in a way that also works for the local community. We’re doing a lot of public outreach and we’re trying to get at a voluntary solution in this watershed. Right now, as we develop the surface water groundwater model, our goal is to make the model and our process transparent. We want to remove that image of the black box, that numbers go in and flow requirements come out.”

The State Water Board specifically chose a public domain modeling platform from the USGS so that the local GSAs could use the model they are developing. The local agencies sit on a technical advisory committee and have been providing data. The model is going to simulate streamflow levels daily and groundwater levels monthly. The model is being built with data from the period 1994-2017.

“We’re really trying to understand the physical system, so we’re putting all the data together, and that leads to policy and that leads to sustainable groundwater management,” Mr. DeLano said. “We’re going to use the model to test different scenarios so if a GSA wants to have different pumping scenarios or you have instream flow dedications, we can use this model to then look to the future and test different scenarios.”

The Thomas Fire burned 82% of the Ventura River watershed; there were streams still flowing in September near the end of the dry season that historically would probably not be flowing at this point, but because so much of the mountain’s part of the watershed burned, all the vegetation has been burned off the mountains, a lot more water is coming downstream. They will use the model to see how it simulates the 2018-2020 post-fire period.

The Thomas Fire burned 82% of the Ventura River watershed; there were streams still flowing in September near the end of the dry season that historically would probably not be flowing at this point, but because so much of the mountain’s part of the watershed burned, all the vegetation has been burned off the mountains, a lot more water is coming downstream. They will use the model to see how it simulates the 2018-2020 post-fire period.

Moderator Jena Acos Shoaf notes that the State Board and DWR are sort of the regulators in terms of SGMA, so how will DWR be looking at models that the State Board or the California DFW put together? Will DWR require GSAs to use those models?

“Modeling is not necessarily required,” said Trevor Jones. “For all practical purposes, looking at the timing and volume of depletion, it’s going to be necessary, because the regs to require using best available science and information. When Melissa put up that undesirable result description related to looking at groundwater dependent ecosystems, I see things a little differently. I am looking at it from a compliance point. Is that description going to meet the requirements of the regulations? Based on what I saw, she was working with the GSAs to establish a water level, so using groundwater levels as a proxy as to what is going to be required to demonstrate what’s undesirable result. So I’m looking at everything from a process standpoint. Did you follow a process of defining significant and unreasonable using quantitative metrics? Minimum threshold is something that was mentioned. That’s just a tool to help define what undesirable results are. … Modeling is a really a tool to understand what projects and actions are needed or to simulate conditions so that you can get an idea of what might constitute a significant and unreasonable condition. That’s why we’re leaned towards minimum thresholds trying to stress the importance of empirical data, because empirical data is really clear, generally, and easy to understand if you’re meeting your thresholds.”

QUESTION: Using groundwater levels as a proxy for the surface water groundwater interaction, without knowing the connectivity, how could that work? If you’ve got groundwater levels increasing away from the stream, that doesn’t tell you anything …

“You’re right, groundwater levels in itself don’t tell you the amount of depletion,” said Trevor Joseph. “But if your beneficial use that you’re trying to protect is groundwater dependent ecosystems, for example … you have to have data, you have to have representative monitoring wells that can characterize the conditions. If your goal is to establish a water level there, and maintain that water level for the benefit of those GDEs, then it works in that example. But it doesn’t work in necessarily or potentially in every beneficial use.”

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!