Karla Nemeth was appointed Director of the California Department of Water Resources by Governor Edmund G. Brown Jr. on January 10, 2018. As the Director, she oversees DWR operations, including maintaining the California State Water Project, managing floodwaters, monitoring dam safety, conducting habitat restoration, and providing technical assistance and funding for projects for local water needs.

At the fall conference of the Association of California Water Agencies held last week in San Diego, Director Nemeth opened the conference with a speech highlighting how the Department is retooling to confront the challenges ahead. In her speech, Ms. Nemeth discussed the challenges of a changing climate, efforts to recruit talented young people to the workforce, investments in new technologies to improve water management, and support for integrated water management.

(Spoiler alert: Ms. Nemeth largely avoided discussing the California Water Fix aka Delta tunnels project; her only comments are toward the end.)

Here is Karla, in her own words.

I got my start in California water first as a consultant, but it wasn’t too long before I realized that I needed to be at an agency, so I really got my start in California water working for a mid-sized water agency in the Bay Area. I was drawn to the practical, no-fail nature of our business. I was drawn to the urgency that accountability brings. And maybe it was the sunset, but I was even drawn to a little bit of romance with the South Bay Aqueduct.

But here I am today, the Director of Water Resources, where those fundamentals of public service still drive me. The challenges though are much more complex and we’re going to need each other if we’re going to meet them. That’s why it’s a privilege for me to be here today among so many water policy leaders talking about our state’s water future and how do we invest today so we have water for tomorrow.

Before we talk about our state’s future, I want to talk about our present. In many ways, that future of changing climate that we’ve all been talking about and starting to plan for – it’s actually here. It’s actually our now. The numbers speak for themselves: As of mid-November, the state had experienced nearly 5800 wildfires since the start of the year; that’s a 9% increase over the last five year period.

But here’s where the numbers get especially scary. The acreage burned in the 2018 fires is 850,000 and that’s a 300% increase over the last 5-year average. If you combine those numbers with the US Forest Service numbers, more than 1.6 million acres have burned in California this year.

These numbers tell us that our fires have intensified, they are harder to manage, and are extreme in ways we’ve never before experienced. These fires are fueled by abnormally hot, dry conditions elevating evaporation rates and dead trees. All of this is exacerbated by climate change.

But it’s not just the numbers of acreage burned that tell us the new abnormal has arrived. We have thousands of people across the state who are displaced by these wildfires, or have even lost loved ones. The folks in Paradise can certainly tell us how climate has changed their lives forever. And in the instance of the Camp Fire, it was actually a November storm that finally put the fire out, but not before putting the area on high alert for flooding.

In the not-too distant past, many of us operated under the assumption that the real impacts of climate change would not hit the human race in a significant way until 2100. We now know that this is not true. We don’t have the luxury of 81 years to plan for the coming extremes. They are here and they are now and we need to step up.

The Department of Water Resources was a significant contributor to California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment. And it paints a difficult picture of California’s future. By 2050, water supply from snowpack is projected to decline by two-thirds and California’s agricultural production could face climate-related water shortages of up to 16% in certain regions. And those fires that we’ve been dealing with, by 2100, the average area burned in California can increase again by 77%.

So we’re going to debate exactly when we might experience the range of climate change, but more precisely, how it manifests itself has a degree of unpredictability, and in that sense, it really is an equal opportunity stressor. No one in this room is impervious, so what do we do about that? I’m going to get to that in a minute, but first I want to reflect on how much we’ve accomplished in the last eight years together.

We’ve already been laying the groundwork that can help us be successful. So together, we championed the successful initiative for the state’s investment of $7.5 billion in stormwater capture, new water storage, desalination, recycling, groundwater management, and ecosystem restoration. Those dollars leveraged much more from local and federal governments and have put California on a path to invest nearly $21 billion in infrastructure and management by 2024.

Through the California Water Action Plan, we have unified a statewide vision that improves water use efficiency, empowers regional self-reliance, and integrates water management across all levels of government, and it supports safe water for all communities. For the first time in our history, California has a framework for managing groundwater basins so that they can continue to support communities well into the future.

But I will tell you, one of the things that gives me most pause is that together, we weathered the deepest drought in modern history. And we did it with minimal impact to the California economy. And we did that because of you. You made the local investments in storage, recycled water, and conservation. Without these investments, the pain to Californians would have been much deeper. I truly believe that.

The drought did expose the vulnerability of some of California’s communities, and we must use our success to motivate ourselves to improve our water supply security when we inevitably experience the next drought.

But just to remind us that Mother Nature bats last and we must plan for her every whim, the driest periods on record became one of the wettest periods on record. In 2017, even with the Oroville spillway emergency, the State Water Project moved more water in a single year than ever before in its history. Decades after that system was built. I can’t think of anything better than the juxtaposition of these two extremes occurring in back to back year to better illustrate the volatility and the complexity of our water system challenges and more importantly, the value of integrating our water supply management more broadly.

So Mother Nature, we hear you loud and clear and we’re going to step up and meet your challenges with everything we’ve got. We need to do more than acknowledge the urgency of the moment and embrace it; a response to new climate realities should be foundational to every action we undertake as water managers. Doing something requires more than just new laws and executive orders. We must lead by example.

At DWR, we’re committed to investing in people. We’re going to recruit the next generation of problem solvers, people who are eager for the challenges that lie ahead. We’re also committed to investing in technology that allows for the real time management of our water systems, improves hydrologic forecasting, protects our water quality, and improves affordability of new supplies. And most importantly, we’re committed to investing in partnerships that enable us to integrate water management across water supply and flood disciplines, across watersheds, across organizations, and in ways that achieve multiple benefits. So I want to take these three prongs in order.

First, we need to hire problem solvers, and we need to start hiring the next generation of leaders. We all need to prepare for the workforce of tomorrow. With an expected wave of retirements in leadership positions, we must work to reorganize in ways that promote innovation and reward problem solving. By the numbers, the cohort immediately following our baby boomers is relatively small, so its incumbent upon us to reach out to millennials and others to share with them the importance of the industry and the immediacy of our work.

The good news is that young people get the seriousness of our global situation. A recent survey by the World Economic Forum found that young people think climate change and the destruction of nature is the most critical global issue. They know that we are at a crossroads.

At DWR, we are brainstorming ways to bring new talent into our workforce, reaching out to college campuses to publicize the breadth of the jobs in this field, and send the message that working in the water industry is working on the front lines of climate change. DWR is expanding its recruitment efforts, supporting pathways to leadership internally, and increasing our public and stakeholder awareness of priorities and accomplishments.

This is an opportunity for all of us in California to position ourselves as global leaders in water in an industry that embraces new technologies, seeks new ideas from other sectors, and actively engages with international professional communities.

We must also embrace new technologies to make our state’s water system more resilient. Statewide, our use of technology to calibrate operations to meet climate variability has increased exponentially in recent years. At the Department, we’re embedding climate change response into every project we undertake. We have set standards to help evaluate how each project incorporates climate resilience principles, and this ensures consistency across the Department.

Last year, through a partnership with UC Davis hydrologic lab and the state’s climatologist’s office, the Department installed forecasting monitors in the Feather River watershed to improve our real-time management of our reservoirs and assist local water managers. The need to narrow the gap in forecasting and improve our ability to predict and plan for variable weather is essential to the deepening boom-bust of California hydrology.

Still more satellite analysis takes a look at carbon storage in forests and water conditions that could lead to hazards with post-fire debris flow and landslides.

In the Delta, our new high-tech smelt camera allows us to count fish populations without having to capture them. With this camera, we can analyze the endangered fish populations and understand where they are and where they are moving to.

And the Sentinel, the Department’s new multimillion dollar research vessel, allows the Department to collect numerous types of data in real time, move throughout the entire Delta more rapidly to assess key water quality parameters that also help us detect the presence of fish and manage our system more efficiently.

DWR has also begun including research institutions in our grant making processes where appropriate with small grants for research institutions to advance desalination technology in ways that protect the environment and provide water at a reasonable cost. It is an important move for the Department to engage with the academic community to make sure that we’re in a position to push out new technologies as we consider our grant making to local water agencies.

Together with other state agencies, we’re also implementing statewide integrated water data platform. This platform will integrate water and ecological data from the Department of Water Resources, the State Water Resources Control Board, and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. This will allow for a more holistic dive into our collective climate environmental data to better inform our decision making. This information will be accessible to local agencies and the broader public for their own use. And with that transparency and consistency, we can ensure that we’re all moving in the right direction together.

In the area of sustainable groundwater, the Department recently created a new visual tool for local agencies and the public to access groundwater data that has been collected over the last 30 years. This consistent and centralized data will improve coordination across the state and help groundwater sustainability agencies meet the new requirements under the sustainable groundwater management act.

These are just a handful of examples of the way the Department is embracing technology, and I think all of it is pretty cool. I can actually think of a few millennials that might be excited to know this is what it means to work in the water industry. It’s not just engineering; we certainly have a few lawyers in our midst. We have hydrologists, and all kinds of A+ people in the industry. But the Department of Water Resources even has a team of back country skiers that ski 100 miles of the Sierra Nevada every year, checking out our snowpack. Who knew if you were into adventure sports, you could have a future of the Department and be part of securing California’s water future?

On a more serious and perhaps substantive note, I want to talk about the next steps in integrated water management. For many decades, Californians survived comfortably with siloed approaches to water management. Water was relatively inexpensive and abundant. We only needed to tap the resource. But not that long ago at the regional level, we began to understand that with a growing population, integrating across hydrologic regions made good sense. It promoted efficiency in water planning and water security across regions. So supporting these efforts remain an important part of DWR’s mission.

However today, with the pressures of a changing climate and aging infrastructure, we need to expand our definition of what it means to integrate. Our emerging sustainable groundwater program will pose new questions at the regional level about what it takes to be water secure. Ultimately, a cross connection between integrated regional water management and the kinds of projects and programs it supports and what it takes to bring groundwater basins into a sustainable yield will need to become standard operating procedure.

Today, 99% of our medium and high priority groundwater basins have formulated local Groundwater Sustainability Agencies to begin to plan and implement ways to move forward to achieve a sustainable yield for their local communities. This need for cross connection is immediately upon us.

Another key area of integration is new efforts to manage floodwaters for aquifer recharge. The concept is to take peak flood flows to recharge depleted groundwater basins. Ideally, reservoir operators would work with downstream flood agencies and local landowners to coordinate the diversion of floodwaters on to private or public lands suitable for groundwater recharge. The potential benefits of this are significant: groundwater replenishment, peak flood flow attenuation, additional values and uses for agricultural land, a potential source of instream flows during drought or other periods of critical environmental need, and finally, increased efficiencies from reservoir reoperation.

The Department is also pursuing an integration of program objectives and what we call multi-benefit projects, ones that can combine water supply, flood protection, and environmental restoration in new ways. The Department itself has created a new division dedicated to this objective. One of the exciting new restoration projects is called Lookout Slough in the Northern Delta. In a nutshell, it really is the quintessential multi-benefit project and one that seamlessly integrates our flood risk reduction needs and our Delta habitat restoration needs. The project is 3000 acres in the Cache Slough region in the northern part of the Delta, and it will open up a floodwater bottleneck at the bottom of a key flood bypass. The area is adjacent to 10,000 acres of existing restoration lands, and when completed, it will produce critical habitat but also critical food resources like phytoplankton and zooplankton that will be exported to rest of the Delta through tidal energy.

Our ability to connect this financially and otherwise with important projects that help reduce flood risk enables the Department to tell a story that we’re focused on the same geography and we’re asking the land to do a lot of different things, and by merging those efforts and doing them together, we can have better and more cost-effective outcomes across the board. To deliver this project, the Department is engaging the private sector to help the project through design, permitting, and construction. Just as the project integrates multiple public values of flood and environmental restoration, the project integrates across sectors, working with the private sector, local agencies, and other state and federal agencies, and academia. These large complicated projects are what we need; they are not easy, but this really is the taste of what’s to come. The multiple public benefits and multiple parties working towards success are a model for DWR’s work in this region and beyond.

I also want to talk about integrating the backbone of the state and federal infrastructure with local infrastructure. The Department as the owner/operator of the State Water Project has a lot of work to do to ensure that the system is ready to deliver water supplies for the next 50 years. We are close to completing an asset management plan that will lay out all the important investments we need to make, but this effort provides an opportunity to upgrade the systems with new technologies that can deliver that water more efficiently.

But what’s equally important is the next generation of water transfers that can enable state water contractors to manage these supplies more flexibly so that they make the most of investments that they are also making at the local level.

In this sense, we acknowledge that California water management has grown up since the project first came online. No longer are the State Water Project supplies the central feature of the water supply portfolio. They are a critical piece that supports overall water supply security.

Perhaps the biggest infrastructure project in the country is WaterFix, and its primary function is to be able to move water supplies more efficiently during storm events. Coupled with real time monitoring and sophisticated fish screens, we can do better for both fish and water users. These supplies are crucial to groundwater management, and they are the supplies we all anticipate will be used more than once, via important water recycling efforts that are now underway. WaterFix has been under development for 12 years in one form or another. We’re very close to final permitting for that project and financing for that project, and it will be a great moment in DWR to be implementing the project. It enables our Department to work on a variety of different ways in which those critical supplies are connected more foundationally to local supplies that everyone in the room here is working to invest in.

Lastly, I want to talk about Oroville. As of November 1st, the Department completed its spillway recovery. Both the gated spillway and emergency spillway are now restored to original capacity, and we now enter a new phase about how to make that dam safer in the long term. Our comprehensive needs assessment is a 2-year process that will be responsive to the forensic team report in terms of new safety measures and a deeper understanding of our geology, but it also provides an important opportunity to update how we manage and operate that reservoir. We can use new technologies that develop forecast-informed reservoir operations which can enable us to do better with both flood protection and water supply and be more nimble in the way that we operate Oroville. It also builds on the cooperation we have with other water users in the next watershed on the Yuba River. All of those connections and integration across watersheds is going to be essential to do the things we need to do to protect the public from flooding, but also to supply important water supplies to many, many Californians.

Finally, I want to talk about how we integrate environmental benefits across watersheds and regulatory regimes. I’ll bet a great many of you in the room are familiar with the Water Resources Control Board’s effort to update the water quality regulations in the Delta and the Sacramento and San Joaquin watersheds. These watersheds drain 2/3rds of California’s runoff so it’s actually pretty difficult to not be interested in this process.

As many of you know, the Department is deeply engaged in efforts to bring voluntary agreements among water districts, Bureau of Reclamation, our sister agency the Department of Fish and Wildlife, and environmental groups to the Water Board for their consideration in lieu of implementing new water quality standards. Opportunity for water users is enormous. 15 years of regulatory certainty, a seat at the table in a more open and collaborative science process to guide the use of financial and water resources, significant and enforceable state commitments to restoring habitat and addressing other limitations on fish species.

But I think the part that intrigues me the most is that we know from decades of experience that flows without physical habitat restoration don’t do the things we need them to do to help make our fisheries more resilient. But what’s becoming even more clear is that investing in one part of the watershed without investment or coordination with another part of the watershed also limits our success. Salmon making its way from the upper watershed down to the Delta, out to the ocean and back again, doesn’t care who has the water right to use the water in which they are swimming, rearing, and moving through their habitat. We do, we most definitely and appropriately do, but the fisheries do not. The voluntary agreements give us an important opportunity as a water user community to help knit these ecological pieces together and to help demonstrate that in fact, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts when we’re working to restore the ecosystems that help us create a more reliable water supply.

It’s going to take an acknowledgment from all of us that all watersheds are not the same, and we need to work across all of them for the most efficient and effective way to support our ecosystem. I’m heartened to look in this room and see the expertise and passion and commitment of so many people who are managing our state’s resources to the highest public benefit and working in partnership to do so. You all know that the stakes are high, we would not get any work of consequence done in Sacramento without your engagement and expertise. And while we may be of varied opinions on many issues, our end goal is clear. We must build a path to a sustainable future using our best science and facing our challenges head on, and we must build strong partnerships too.

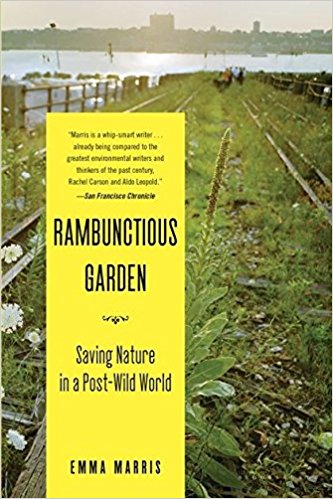

In this time of multiple and intensifying challenges, I like to think of our mission as embracing the notion of ourselves as stewards of ‘rambunctious garden.’ Rambunctious garden is a term coined by writer Emma Marris. The premise is that we are at a place and time where we cannot return nature to its pristine pre-human state and we need to accept that and plan for our future with that awareness. We must accept that humans have altered our landscape irrevocably and from here we must use our best science and conservation techniques to create a rambunctious garden, a hybrid of wild nature and human management that we responsibly and innovatively tend.

In this time of multiple and intensifying challenges, I like to think of our mission as embracing the notion of ourselves as stewards of ‘rambunctious garden.’ Rambunctious garden is a term coined by writer Emma Marris. The premise is that we are at a place and time where we cannot return nature to its pristine pre-human state and we need to accept that and plan for our future with that awareness. We must accept that humans have altered our landscape irrevocably and from here we must use our best science and conservation techniques to create a rambunctious garden, a hybrid of wild nature and human management that we responsibly and innovatively tend.

This is an apt description for this moment in California, and tending to and developing this rambunctious garden of our state should be our guiding principle and narrative. What I like about the idea is that it doesn’t put forth a false binary choice between environmentalism and infrastructure planning and water management. These days, both so-called environmentalists and water buffaloes are more likely to have PhDs in environmental science and be working together on satellite monitoring of groundwater levels or state of the art fish screens or bringing a desalination plant online.

We had our era of big infrastructure, that pioneering era where some of our best minds constructed the largest state water system in the nature, bringing water in the Sierra to regions throughout the state. That era essentially built California into the economic powerhouse it is today. Then we have the new era of environmental laws that required a shift in operations, a shift away from our thinking, a shift in a way that we thought about and managed water. We are still working to meet these challenges but through science and innovation we’re making great strides. And now it’s our aging infrastructure, complex environmental challenges associated with managing these rambunctious garden and the intensifying pressures of climate change that drive us.

So let’s invest. Let’s invest in people, let’s invest in technology, and let’s take that next step in integrating our water management system. Let’s do this work together.

I thank you for this opportunity to address you this morning, and open the ACWA conference. May it be a great success.”

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!