Data shows groundwater recharge in the region has declined by 1.1 MAF since 2000; storage remains at unhealthy levels

At the October meeting of Metropolitan’s Water Planning and Stewardship Committee, Senior Engineer Matt Hacker updated the committee members on regional groundwater conditions, including groundwater production, recharge, and storage conditions.

There are 88 groundwater basins and subbasins within the Metropolitan service area. Groundwater provides over 1/3rd of the region’s water supplies. 89% of the basins within the Metropolitan service area either are adjudicated or managed.

There are 88 groundwater basins and subbasins within the Metropolitan service area. Groundwater provides over 1/3rd of the region’s water supplies. 89% of the basins within the Metropolitan service area either are adjudicated or managed.

Groundwater production data is tracked annually through local resources production survey, information exchange with watermasters and member agencies, and is confirmed every 5 years through the Integrated Water Resources Plan (IRP) process.

Mr. Hacker presented a graph with precipitation data from two stations, one in the Orange County Basin and the other in the Main San Gabriel Basin. The highest precipitation was in 2005 at 35 to 40 inches; 2011 was a wetter year with just over 20 inches in rainfall; and in 2017, there was just over 20 inches.

Mr. Hacker presented a graph with precipitation data from two stations, one in the Orange County Basin and the other in the Main San Gabriel Basin. The highest precipitation was in 2005 at 35 to 40 inches; 2011 was a wetter year with just over 20 inches in rainfall; and in 2017, there was just over 20 inches.

“Overall, the trend since 2000 has been downward,” Mr. Hacker said.

Mr. Hacker next presented a slide showing stormwater recharge, noting that it is similar to the precipitation numbers. He pointed out that 2005 was the high at about 900,000 acre-feet; however, in 2011 with the 20” of rainfall, there was 600,000 acre-feet of recharge and in 2017, with the same amount of 20” of rainfall, there was only 400,000 acre-feet of stormwater recharge. He explained that it had been dry for many years so a lot of the water was consumed in the watershed area, so not as much came down to our spreading grounds.

Mr. Hacker next presented a slide showing stormwater recharge, noting that it is similar to the precipitation numbers. He pointed out that 2005 was the high at about 900,000 acre-feet; however, in 2011 with the 20” of rainfall, there was 600,000 acre-feet of recharge and in 2017, with the same amount of 20” of rainfall, there was only 400,000 acre-feet of stormwater recharge. He explained that it had been dry for many years so a lot of the water was consumed in the watershed area, so not as much came down to our spreading grounds.

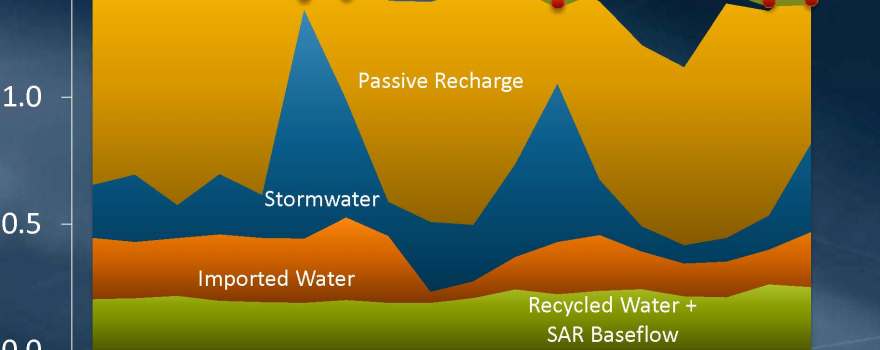

He then presented a chart showing groundwater recharge from all different sources, noting that recharge has been declining since 2000. The green on the bottom is the recycled water and Santa Ana River baseflow; it has generally increased a little bit. The orange is imported water which can be quite variable; he noted that recently, some of the basins are recharging more water in 2017 and beginning of 2018. The shaded blue area represents stormwater.

He then presented a chart showing groundwater recharge from all different sources, noting that recharge has been declining since 2000. The green on the bottom is the recycled water and Santa Ana River baseflow; it has generally increased a little bit. The orange is imported water which can be quite variable; he noted that recently, some of the basins are recharging more water in 2017 and beginning of 2018. The shaded blue area represents stormwater.

Passive recharge is the largest component. Passive recharge is defined as water that falls naturally onto the ground in areas that are not captured in spreading basins, such as backyards, mountain front recharge, subsurface inflow between basins. Mr. Hacker noted that’s been generally declining since 2000. The line represents groundwater production; he noted that before 2000 and even in some years between 2000 and 2004, there’s a smaller difference between groundwater production and recharge; those are more balanced conditions.

“Think about it this way: when the total amount of storage is below production, that means water is coming out of storage,” he said. “When water is above the line, that’s water going into storage. So if you look at the line 2008 to 2010, those were drought conditions and water was coming out of storage. … The period between 2011 and 2015 was actually a bigger rainfall area but we’re not getting as much recharge. More water is coming out of storage. Then in 2017, you can see in the chart, we’re barely above. It’s a wet year, so we want this to be quite a bit above the line.”

He then presented a slide showing overall storage, noting that it’s an upside down chart on purpose. “The idea is that this is meant to mimic what groundwater levels are doing, so as the chart goes downward, so do groundwater levels,” he said. “The healthy storage range here is shown in the orange, so it goes from about 3.2 to 4.3 MAF of storage which is the area the groundwater basins are targeting. As you can see in this chart, for the last four or five years, we’ve been actually quite a bit below that, so we have actually lost about 1.1 MAF of storage since 2000, and 1.4 MAF since 2005. That’s not a good situation that we really want to be in for the region.”

He then presented a slide showing overall storage, noting that it’s an upside down chart on purpose. “The idea is that this is meant to mimic what groundwater levels are doing, so as the chart goes downward, so do groundwater levels,” he said. “The healthy storage range here is shown in the orange, so it goes from about 3.2 to 4.3 MAF of storage which is the area the groundwater basins are targeting. As you can see in this chart, for the last four or five years, we’ve been actually quite a bit below that, so we have actually lost about 1.1 MAF of storage since 2000, and 1.4 MAF since 2005. That’s not a good situation that we really want to be in for the region.”

The next slide compared historical production to the forecasts in the IRP. Historical production within the Metropolitan service area has declined from about 1.4 to 1.1 MAF between 2000 and 2017, a drop of about 25%. The 2010 and 2015 IRP targets are shown, and the 2017 actual amounts are a bit lower than that.

The next slide compared historical production to the forecasts in the IRP. Historical production within the Metropolitan service area has declined from about 1.4 to 1.1 MAF between 2000 and 2017, a drop of about 25%. The 2010 and 2015 IRP targets are shown, and the 2017 actual amounts are a bit lower than that.

“That’s going to be concerning for us if we’re looking at balancing out our overall supplies in the region and meeting our IRP targets and making sure that we all have enough water,” Mr. Hacker said.

Mr. Hacker then presented a table showing data from some of the individual basins. Looking at the change of storage since 2000, most of the basins have been declining, some more than others. Most of the basins are still within their operating range, although some portions of them may not be. Orange County actually went up a bit and has been pretty much the same since 2000. Main San Gabriel and ULARA (or the San Fernando Basin) are actually below there operating range. He explained that the ones with the question marks on the bottom are the areas where it’s really not clear whether they are in the operating range with respect to storage or not, because there are targets for water level, but not necessarily for storage.

Mr. Hacker then presented a table showing data from some of the individual basins. Looking at the change of storage since 2000, most of the basins have been declining, some more than others. Most of the basins are still within their operating range, although some portions of them may not be. Orange County actually went up a bit and has been pretty much the same since 2000. Main San Gabriel and ULARA (or the San Fernando Basin) are actually below there operating range. He explained that the ones with the question marks on the bottom are the areas where it’s really not clear whether they are in the operating range with respect to storage or not, because there are targets for water level, but not necessarily for storage.

“The overall change in production since 2000 has been between 20 and 25%; most of the basin areas here are down in overall production for a variety of different reasons,” he said. “Some of them are because they have other local supplies so that they don’t need to pump as much groundwater; other ones are a lowering of demand and they don’t have much imported water so when demand goes down, so does groundwater production, and a variety of other issues. Raymond basin actually took a step in their basin to reduce their pumping rights by 30%, so you’re going to see a big jump down as they made the decision to do that.”

Mr. Hacker then looked at some specific basins. He started with Orange County, noting that they have a lot of recycled water that they use in their basin and in general, both of their recharge and groundwater production have been relatively stable (lower, left). “Even though the BPP (or the basin pumping percentage which is based upon demand) may change, and even though their demand has gone down, they’ve increased their BPP which has allowed them to maintain the same level of production.”

He pointed out that their storage has actually gone up a little bit since 2000 (above, right). “During the drought, they performed really well, staying within their basin operating range for the entire period of the last ten years.”

In the Main San Gabriel basin, both production and reduction is declining (lower, left). He noted that this basin responds really well to stormwater; there is a lot of stormwater and a lot of passive recharge in their basin. Groundwater production has gone down because their overall demand has gone down significantly. “They don’t take much imported water here or recycled water, so their groundwater number is really tied to the overall demand,” he said.

The Main San Gabriel basin has been below their operating range since 2014.

“In summary, precipitation and recharge have declined over the last 20 years,” said Mr. Hacker. “The loss in groundwater storage since 2000 has been 1.1 MAF. 2018 storage is expected to be about the same as 2017. Our current deficit in groundwater storage is about 800,000 acre-feet below the low end of that healthy range, so additional recharge is needed to maintain existing levels of production and maintaining existing levels of production is essential for achieving the IRP local supply targets.”

DISCUSSION PERIOD

Director Fern Steiner noted that some of the basins, such as San Gabriel, have an issue with taking Colorado River water due to salinity issues which could affect their numbers as the Main San Gabriel is one of the basins that is not within operating range right now.

General Manager Jeff Kightlinger noted that some of the basin watermasters have been looking to limit salinity at about 500 ppm, but the Colorado River has 600-700 ppm. “It’s better if we have a blend for those areas, but it’s not a legal requirement; it’s more a [basin management plan] target,” he said.

Unknown director (sorry) added that there’s an anti-degradation requirement that makes it a lot more complex. It doesn’t mean it can’t be done, he said, but it has to be balanced with a lower salinity source. It depends on the Salt and Nutrient Plan for the basin.

Director Unknown then said it would be helpful to know what the maximum recharge capacity is for each of the basins. Matt Hacker agrees, says one basin he does know off the top of his head is the Main San Gabriel basin, which can infiltrate an impressive 400,000 to 500,000 acre-feet in a single year.

Director Russell Lefevre notes that if Upper San Gabriel can take on 400,000 to 500,000 acre-feet per year, but they haven’t taken on anything for past 5 years, what are they going to do? It’s one thing to say we need to get additional recharge, where is it going to come from?

Mr. Hacker notes there are a lot of different basins that rely a lot on local resources like stormwater, and when it doesn’t rain, there are other supplies and other projects.

“The major reason Metropolitan was created was to bring in water, and the places like the San Gabriel Valley that had adequate supplies really pushed for joining Metropolitan to bring in Colorado River Aqueduct water for replenishment back in the 1930s,” he said. “Then we have this other project we’re building in California to help bolster the reliability there because that State Water Project water comes at a much lower salinity and can also be added to that recharge, and that’s part of the plan.”

Director Larry McKenney directs to slide 11. He notes that at about 2007-2008, the imported water dropped off precipitously and suggests this coincides with the board’s decision to change the rate structure and remove the replenishment rate. “There may be something to note about our rate structure and incentivizing storage,” he said. “I didn’t have the pleasure of being on the board at the time when they considered the rate structure change to remove the replenishment rate, it may have been well thought out, but it may be something worth going back and thinking about.”

Director Larry McKenney directs to slide 11. He notes that at about 2007-2008, the imported water dropped off precipitously and suggests this coincides with the board’s decision to change the rate structure and remove the replenishment rate. “There may be something to note about our rate structure and incentivizing storage,” he said. “I didn’t have the pleasure of being on the board at the time when they considered the rate structure change to remove the replenishment rate, it may have been well thought out, but it may be something worth going back and thinking about.”

Director Tim Smith notes that passive recharge is the biggest amount of recharge. “Isn’t part of the issue that the irrigation water is no longer replenishing the groundwater basins, and that in fact, we’re part of the problem with our efficiency? This is the trouble with water agencies, we’re telling people not to buy our product. We have turf rebates, but you can see the physical effect of that right here on this chart.”

“There are a number of incidental issues associated with conservation and you see it in the sewer and the wastewater industry with their flow challenges sometimes they have,” said General Manager Jeff Kightlinger. “We see it also in recycled water availability as you conserve that water, and then there’s this passive recharge issue, that’s another incidental issue with water conservation. I don’t know if it’s unintended but it is incidental.”

“The impact on rainwater infiltration versus the reduction in irrigation is night and day,” asserted Director Mark Gold. “I’m not saying there wouldn’t be an impact, but it would be a very small percentage, compared to the fact that we just didn’t have any rainfall during that period, and that’s really where the lion’s share of that is. I couldn’t let it go by letting everyone think that the problem is we’re not irrigating our lawns enough. We really need to get that water back in the groundwater basin but it’s really more of a precipitation issue.”

Director Glen Peterson disputes Director McKenney’s suggestion that removing the replenishment rate is the problem. “To me, water is water, and whether you put it in the groundwater basin or whether you put it in a reservoir or whether you use it, it’s being beneficially used in my mind. We did have many, many years ago incentives which were called interruptible rates. The problem is that Met never interrupted anybody any time, ever. … I would ask how sensitive is all this to pricing because I think that may be the major driver in this. We put 1.1 MAF in storage last year. We could’ve sold a little bit of that.”

“This is all information for us to look at in how we work with our groundwater partnership agencies, and we should be looking thoughtfully and carefully at the tools Metropolitan has, which aren’t many,” says Mr. Kightlinger. “We don’t manage the basins. We have price as a tool. Our in-lieu program has been a tool to incentivize people to shift of their groundwater basin and buy directly from Metropolitan. And there’s a couple of other levers we have and we should be looking at how do we partner with our groundwater agencies to get them to restore some of this yield from these basins. We had this debate and the board strongly felt that they did not like the discount program and that’s the reason we went away from it. We should look at other types of tools we have.”

Director Richard Atwater points out that soils and geology really determine whether you can recharge in that area, and in over half of the service area, infiltration from overwatering your lawn or agriculture wouldn’t result in water getting into any usable aquifers. “You have to remember, it’s all about the soils and the geology. … You have to be really smart where you recharge.”

More importantly, with the effects of climate change with more intense rainstorms, the storm events are getting bigger and coming during shorter periods so it’s harder to capture, continued Director Atwater. “Two years ago if you added up between the city of LA surplus supply and Metropolitan, we could have put a lot more water, at least a half a million acre-feet into the groundwater basins if we all coordinated our efforts. That’s a regional challenge – not that Metropolitan itself could solve the problem, but that’s the kind of collaboration we need to have. We don’t know when the next big wet year is, but after listening to the story about the Colorado River, we’d be really wise to focus on how to do that really well, and have a strategy so when we have another big wet year, we have our act together.”

Assistant General Manager Deven Upadhyay notes that there have been changes to policies related to in-lieu water, which is an effective way of getting water into the basins. He notes that in 2008-2009, they had not changed the replenishment rate; he attributed the change to implementation of the allocation plan. “We implemented our allocation plan in 2009 and 2010, you saw a drop off in imported deliveries and the reason was because in our allocation plan, we had not included replenishment deliveries in the baseline available for agencies. Later on, your board asked us to revisit the allocation plan and make adjustments, and we included water for replenishment in the baselines for the agencies to be able to take … you see some imported deliveries there because we had actually adjusted to allow for it under the allocation, so that was a pretty big piece. Even more than prices, it was that when we were declaring an allocation, we were allowing deliveries in that baseline for the agencies that needed it.”

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!