The Delta Watermaster leads a panel discussing a recent study that compared 7 different methods for estimating consumptive use of crops grown in the Delta

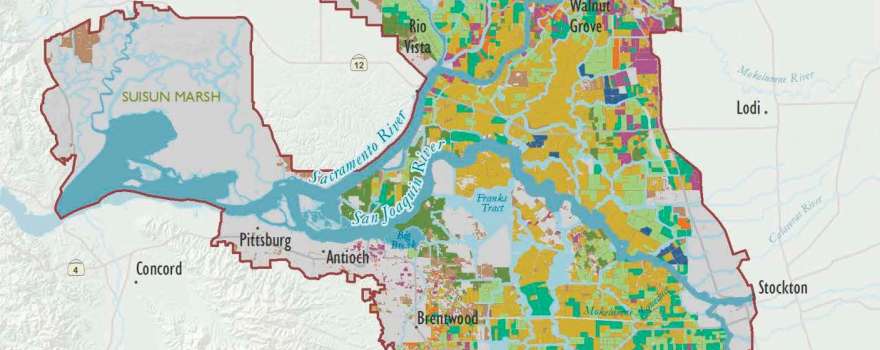

At the May meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, Delta Watermaster Michael George discussed the recently completed study: A Comparative Study for Estimating Crop Evapotranspiration in the Delta which compared seven different models and methods of estimating the consumptive use of different crops grown on the Delta’s numerous islands. Considering that agriculture accounts for the vast majority of land use within the Delta, the consumptive use or evapotranspiration of crops grown there is important for managing water as it flows in and through the Delta’s channels, the hub of California’s water system.

Considering that agriculture accounts for the vast majority of land use within the Delta, the consumptive use or evapotranspiration of crops grown there is important for managing water as it flows in and through the Delta’s channels, the hub of California’s water system.

The Delta is both a transfer point for water stored in reservoirs on upstream tributaries and a source of otherwise free-flowing water for in-Delta water-rights holders. While the amount of water diverted from the Delta by the State and federal water projects is well known, less is known about the amount of water taken and consumptively used (meaning not otherwise returned to the Delta in forms such as waste flow or runoff) by local in-Delta diverters. This consumptive use is measured as evapotranspiration, which is defined by the USGS generally as the water lost to the atmosphere from the ground surface, evaporation from the capillary fringe of the groundwater table, and the transpiration of groundwater by plants whose roots tap the capillary fringe of the groundwater table.

Given the State’s system of cascading water rights in which upstream return flows are factored into downstream water rights, measuring and understanding consumptive use within the Delta is important not only to farmers but also to water facility managers, water rights regulators, and to those seeking to protect the Delta’s human and natural ecosystem.

Given the State’s system of cascading water rights in which upstream return flows are factored into downstream water rights, measuring and understanding consumptive use within the Delta is important not only to farmers but also to water facility managers, water rights regulators, and to those seeking to protect the Delta’s human and natural ecosystem.

Delta Watermaster Michael George began by noting that this study was designed to compare the different ways of estimating crop evapotranspiration in the Delta, a significant challenge because the Delta is essentially a black box. “We know quite a bit about what flows in, we know something about what flows out, and what’s taken out in the Delta, but we lack accurate information about both the timing and the nature of consumptive use of crops,” he said. “About 70% of the Delta is devoted to cropland, so understanding how and when those crops use water is an important factor in determining what we can do in terms of improving management of that most precious resource in the system.”

The lack of accurate and timely understanding of crop consumptive use hampered water management and regulation during the multiyear drought; however estimating crop consumptive use is inherently difficult in the complex setting of the Delta, he said. The Delta is big, varied, complex, and hard to figure out. Land use is very dynamic; it’s not static, a field that was devoted to tomatoes this year maybe devoted to alfalfa next year and may be migrating into grapes or orchards in the following year. Land use decisions in the agricultural sector is critically important to what the demands are and how water is used in the Delta, Mr. George said.

The lack of accurate and timely understanding of crop consumptive use hampered water management and regulation during the multiyear drought; however estimating crop consumptive use is inherently difficult in the complex setting of the Delta, he said. The Delta is big, varied, complex, and hard to figure out. Land use is very dynamic; it’s not static, a field that was devoted to tomatoes this year maybe devoted to alfalfa next year and may be migrating into grapes or orchards in the following year. Land use decisions in the agricultural sector is critically important to what the demands are and how water is used in the Delta, Mr. George said.

“How we regulate extractions from the Delta both internally and for export, how we manage those projects, how we administer the water rights system, and very importantly, how we manage the evolution of agriculture and ecosystem restoration in the Delta depends on understanding these relationships,” he said.

The study originated at the suggestion of then-Vice Chair of the State Water Resources Control Board, Fran Spivy-Weber, with help from fellow board member Tam Doduc. They pulled together a ‘coalition of the willing’, which was a wide variety of people who had an interest, who could contribute to the understanding, and who would be meaningfully impacted by what was learned; they came together voluntarily to look at the state of the current science, he said.

The study originated at the suggestion of then-Vice Chair of the State Water Resources Control Board, Fran Spivy-Weber, with help from fellow board member Tam Doduc. They pulled together a ‘coalition of the willing’, which was a wide variety of people who had an interest, who could contribute to the understanding, and who would be meaningfully impacted by what was learned; they came together voluntarily to look at the state of the current science, he said.

The coalition articulated organizing principles:

- They would include a broad array of stakeholders, work to maintain neutrality and credibility; assure representation of multiple perspectives; attract funding, and consistent review of progress;

- They would focus on practical application and informative comparisons (not pure science);

- They would improve utility of all methods through peer-to-peer collaboration and not have the study be a contest to pick a winner.

The study identified seven models and methods for estimating consumptive use in the Delta which have been developed; all of them had been subject to peer review and were methods that are in wide use.

“We recognized that there had been a lot of science and rapid development in these technologies, so we wanted to compare and contrast them, make them all better, and figure out how to use them more intelligently,” Mr. George said. “In the course of comparing these seven different methods, all those methods did improve, and that was important. We brought people who were deep into their silos that had a specific method that they had developed at their university or at their consulting firm, and exposed them to each other in a way identified ways that each of these methods could improve. We were not trying to pick a winner; we were trying to make them all better, understand them better, and recognize their strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities.”

The study was funded by state agencies, including the State Water Resources Control Board, the Department of Water Resources, the Delta Stewardship Council, and the Delta Protection Commission as well as the in-Delta water agencies; there were also significant in-kind contributions. Research participants included the USDA, and private consultants.

STUDY ORGANIZATION

Jesse Jankowski, Graduate Research Assistant Center for Watershed Sciences, then described how the study was organized.

There were seven different models and methods for estimating consumptive use; the goal was for each of the methods to have a separate and independent sponsor that would subject to them to comparison and allow collaboration to improve all of them collectively, he said. Two of those models are used by the Department of Water Resources for water planning both statewide and specifically within the Delta; five of them were from academic and federal teams that use remotely sensed satellite imagery to develop estimates of evapotranspiration.

The UC Davis Land, Air, and Water Resources department captured field level calibration data for these models by setting up meteorological weather stations similar to the CIMIS network, but it was an independent effort dedicated to the study. The Center for Watershed Sciences team acted as the central team that collected, organized, maintained, and analyzed all of this data produced in the study without being intimately involved with any one of the models.

The UC Davis Land, Air, and Water Resources department captured field level calibration data for these models by setting up meteorological weather stations similar to the CIMIS network, but it was an independent effort dedicated to the study. The Center for Watershed Sciences team acted as the central team that collected, organized, maintained, and analyzed all of this data produced in the study without being intimately involved with any one of the models.

The study was also aided by a land use survey contracted by DWR which supported ground-truthing efforts in the Delta. “It gave us on a 30 by 30 meter level, every field and identification for what the land use was and it was particularly focused on agricultural lands,” he said. “We had about 25 different crop categories and another about 5 non-agricultural land uses that were identified in that study.”

All of the results of the blind tests and methods were submitted and analyzed, utilizing common data sets; each of the models improved with the final year of study. They then looked at detailed comparisons between the models which allowed them to understand why the results may be similar or different for certain areas and certain crops at different times of the year.

“All of these things really allow for collaborative benefits from the improved CIMIS network and from land use data which will be made available eventually by DWR,” said Mr. Jankowski. “It allows for multiple different benefits to this study and beyond.”

PRIMARY FINDINGS

One of the first findings was that averaging all of the seven methods, they estimated  about 1.4 MAF per year of consumptive use in the Delta, Mr. Jankowski said. “That’s water leaving that black box each year from agricultural lands, from those croplands which is about 75% of the Delta,” he said. “Although that’s certainly valuable, it is pretty consistent with the mass balance estimates that DWR uses. We get a lot more intimate knowledge in terms of the spatial differences going down to the field level as well as the monthly estimates within those water years of ET.”

about 1.4 MAF per year of consumptive use in the Delta, Mr. Jankowski said. “That’s water leaving that black box each year from agricultural lands, from those croplands which is about 75% of the Delta,” he said. “Although that’s certainly valuable, it is pretty consistent with the mass balance estimates that DWR uses. We get a lot more intimate knowledge in terms of the spatial differences going down to the field level as well as the monthly estimates within those water years of ET.”

The accuracy of all these methods with the collaborative interaction and improvements in common datasets did improve their agreement on the nature of evapotranspiration; all methods by the end of the study were brought within 11% of the mean across all seven of them and in many cases, much less than 11%, said Mr. Jankowski, noting that plus or minus 10% is very good for a region as large as the Delta.

However, Mr. Jankowski said the study did illuminate some systemic differences between the different methods that are inherent to the assumptions and the modeler judgement required as an input to these types of estimates; these things may not always agree due to unique aspects of each model. “Nevertheless, these remote sensing methods that are using the satellite data provide a very reasonable estimate basis for estimating crop ET, specifically within the Delta and elsewhere,” he said.

However, Mr. Jankowski said the study did illuminate some systemic differences between the different methods that are inherent to the assumptions and the modeler judgement required as an input to these types of estimates; these things may not always agree due to unique aspects of each model. “Nevertheless, these remote sensing methods that are using the satellite data provide a very reasonable estimate basis for estimating crop ET, specifically within the Delta and elsewhere,” he said.

Mr. Jankowski noted that the methods are ever-evolving. “This remote sensing field is a rapidly growing within the scientific community and the frequency of observation especially is going way up,” he said. “In the next couple of years, there are multiple different satellites planned to launch that will really increase the frequency and the resolution of this type of data and allow for much greater improvements in terms of the accuracy of these ET estimates.”

The seven methods that the study compared varied widely in terms of the cost required to implement them, the expertise from the people operating them, the invasiveness of if ground level calibration data is needed or if it’s all satellite-collected data, the frequency of the estimates, and how consistent they are, especially in a widely varied place like the Delta.

The seven methods that the study compared varied widely in terms of the cost required to implement them, the expertise from the people operating them, the invasiveness of if ground level calibration data is needed or if it’s all satellite-collected data, the frequency of the estimates, and how consistent they are, especially in a widely varied place like the Delta.

The major focus of the study was crop consumptive use from agricultural lands, which was estimated at 1.4 MAF; however, Mr. Jankowski pointed out that a significant portion of consumptive use in the Delta may originate from non-agricultural lands, such as open water in the channels, urban areas, or particularly natural vegetation.

“The land use classes these surveys put out did not differentiate between invasive or native vegetation, but that includes things like upland grassland areas, rangelands, riparian zones, and floating vegetation,” he said. “Things like that might have very valuable implications for how this data can be used for policy makers.”

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Next, Dr. Josué Medellin-Azuara, Associate Director of UC Agricultural Issues Center at UC Merced, discussed some of the policy implications for the study. “I am convinced that this study demonstrates the capacity of the agencies, the participants, and the scientific community stakeholders to collaborate in estimating crop evapotranspiration and consumptive use at the field level,” he said.

The policy questions that rose from the study:

- Are these estimates ‘close enough for government work’? “In the study, one of the big findings is that consumptive use is one of the largest pieces of the water balance in the region, especially a region that is predominantly agricultural with a large proportion of the land use classes in agriculture; this piece is pretty fundamental in estimating the water balance,” Mr. Medellin-Azuara said. “However, this piece is often not very popular in estimating, and there are a lot of methods to estimate that and some uncertainties associated with it. So can we get ‘close enough for government work’? This will entail some policy calls on how much of the uncertainty we can incorporate to use this for regulation.”

- What is the process or value for government agencies on converging on a consumptive use methods across agencies? “We’ll probably never get close enough,” he acknowledged. “We did a pretty nice job in making this conversion close to 11%, 10% across all methods. That was quite an achievement after three years of working with all these independent groups. However, we must keep in mind that real money is associated with uncertainties. In dry years, 10% over a large area like the Delta can be real money for some of the stakeholders, so we can certainly attribute some value to that uncertainty.”

- How can we adopt the scientific research for practical use? “Consumptive use is just one piece of the water balance,” Mr. Medellin-Azuara said. “There are other pieces which are the diversions, what goes into groundwater, and what goes into drainage; all these elements play a role and incorporating these pieces into operations for regulation or for land use management, for agriculture and land use management. This has some value and needs to be further explored.”

- How can policy encompass uncertainties in estimates? “How do we use an ensemble of models to see what is the mean value and use that as our rebuttable presumption on what the consumptive use is in a specific field or in an area and how we incorporate the uncertainty associated with that? Can we put lower and upper bounds, or just agree on an ensemble approach and have a mean value?”

- How closely does crop consumptive use correlate with diversion measurement? “Measurement of this can offer some sort of substitute, provided a clear correlation exists. This is one of the things we are studying next in the area.”

NEXT STEPS

Mr. Medellin said they have thousands of data points of evapotranspiration estimates for each of seven fields for two years; it is material for a thesis or future studies and is worthwhile examining. However, at this point, they feel they have already obtained great insights. “We have a lot of data points to explore about how conversions of one meadow might decrease using more standardized datasets and other assumptions,” Mr. Medellin-Azuara said.

Mr. Medellin said they have thousands of data points of evapotranspiration estimates for each of seven fields for two years; it is material for a thesis or future studies and is worthwhile examining. However, at this point, they feel they have already obtained great insights. “We have a lot of data points to explore about how conversions of one meadow might decrease using more standardized datasets and other assumptions,” Mr. Medellin-Azuara said.

More research is needed on the evapotranspiration of fallowed fields. Mr. Medellin-Azuara said there is a limited bare soil evapotranspiration estimates; over the course of the study, it was realized that they would benefit from having an expanded field campaign on bare soil, so this is in the ongoing study this year. Also, a large proportion of the consumptive use in the Delta that comes from non-agricultural land use classes, so having some estimates on non-crop water use is also a fundamental piece.

There was recently a workshop organized by the Environmental Defense Fund and other organizations for an initiative called Open ET, which has some funding from foundations such as the SD Bechtel Jr Foundation and the Water Foundation and others. “It resembles a consortium sort of approach within technical groups, agencies, and stakeholders in pursuing a study of Open ET or evapotranspiration on a open access basis,” said Mr.Medellin-Azuara. “That increases the transparency, that increases the accuracy of the estimates and cooperation among stakeholders, universities, and others, so we participated in that workshop in various capacities.”

There was recently a workshop organized by the Environmental Defense Fund and other organizations for an initiative called Open ET, which has some funding from foundations such as the SD Bechtel Jr Foundation and the Water Foundation and others. “It resembles a consortium sort of approach within technical groups, agencies, and stakeholders in pursuing a study of Open ET or evapotranspiration on a open access basis,” said Mr.Medellin-Azuara. “That increases the transparency, that increases the accuracy of the estimates and cooperation among stakeholders, universities, and others, so we participated in that workshop in various capacities.”

They will also be evaluating the hypothesis that remote sensing could augment diversion measurement in the Delta to see if this could be a surrogate which would reduce the burden for self-reporting on diversions and other issues, he said.

“I think we have made an important progress with this study on a gnarly problem, but we still have a lot of work to do,” Mr. Medellin-Azuara said. “We truly appreciate all the interest from the community on making this happen.”

“I think we have made an important progress with this study on a gnarly problem, but we still have a lot of work to do,” Mr. Medellin-Azuara said. “We truly appreciate all the interest from the community on making this happen.”

Watermaster Michael George said it will be a game changer to know in real-time (or close to real-time) what the water use is as compared to what we known in the past and what they were dealing with in the drought. “The ability to use remote sensing to come up with an accurate estimate of what’s happening today or now or next week to forecast or to look back and to say, for instance, what is the water use implication of moving from a field of alfalfa to putting in trees,” he said. “Initially the water use goes way down, because you’ve just got little sticks out there, but you can, as soon as you see that happen, from the satellite, you can predict a 30 year water budget for that field. That’s an incredible game changer.”

DISCUSSION HIGHLIGHTS

Councilmember Mike Gatto asked about water use in the Delta. If somebody owns a farm or buys a farm, can they pump whatever water they need?

Watermaster Michael George noted that it was the wisdom of the legislature that the authority to administer water rights that came into existence prior to 1914 is outside the administrative authority of the State Water Board. “In the Delta, that’s most of the water use. It’s either riparian or pre-1914 water rights, so up until we had emergency authority granted in the course of the drought, there was never a way for the State Water Board to even ask people how they were exercising their water rights.”

“It sounds like the need for this study was that there are very few water users in the Delta who are metered as we tend to think of it,” said Mr. Gatto.

“It sounds like the need for this study was that there are very few water users in the Delta who are metered as we tend to think of it,” said Mr. Gatto.

“You’re correct, and that’s not unique to the Delta,” said Michael George. “There are lots of places in California where the amount of water ETd in the ag sector is not measured. There are a lot of places where it is measured, typically where there is a per unit consumptive use charge. In any case, in the Delta, this is an area that was swamp and overflowed lands, it’s riparian in nature and riparian water rights are not quantified, so you’re allowed to use as much water as you can put to beneficial use on the property; that’s a bedrock. It was one of the conditions for California becoming a state in 1850 that we adopted the common law. It wasn’t quite well suited to arid California, but that’s what we did.”

“What I do want to say is that in the period since 2014, we’ve made enormous strides getting information about all these senior water rights,” Mr. George continued. “We’ve created the first taxonomy of senior water rights in the Delta, we are going through an extensive ground truthing exercise right now, all aimed at learning the lessons from the last drought, and being able to be more transparent and apply that information going forward.”

“The estimate of 1.45 MAF in 2015, did that surprise anybody?” asked Mr. Gatto.

“The Delta Plan in 2013 estimated a range of in Delta water use at .7 MAF to 1.1 MAF with an average of .9, so this is a 50% increase over that estimate,” said Jessica Pearson, Executive Director.

“What we’re talking about with the 1.45 MAF is the crop consumptive use,” said Michael George. “One of the things this study demonstrated that probably 30% or more of water use in the Delta – water leaving the black box – is non-agricultural water use. It’s evaporation from open water, it’s transpiration of floating weeds which transpire at a much higher rate than terrestrial flora, and in addition, you have changes in land use that are happening pretty rapidly in the Delta.”

“What we’re talking about with the 1.45 MAF is the crop consumptive use,” said Michael George. “One of the things this study demonstrated that probably 30% or more of water use in the Delta – water leaving the black box – is non-agricultural water use. It’s evaporation from open water, it’s transpiration of floating weeds which transpire at a much higher rate than terrestrial flora, and in addition, you have changes in land use that are happening pretty rapidly in the Delta.”

“Agriculture in the Delta probably returns some of the water better than transported water, let’s say to Kern County, for example, because the pumped water goes back into their groundwater table, but here it goes back into the table that feeds the Delta in some way,” said Mr. Gatto. “Is there any estimate of what percent of water that is used for agriculture makes it way back into the table that actually feeds the Delta?”

“Recognize that what we were trying to measure, what all these methods do, is figure out how much water leaves the system, so we’re looking at net evapotranspiration,” said Mr. George. “There are four legs to the stool: How much water is being drawn out of the Delta or the diversion; how much is being consumptively used or the evapotranspiration; how much is seeping in and seeping out because much of the farming in the Delta is below sea level; and what is being pumped off of the island back into the channels. … Particularly in the Central and western part of the Delta, among the largest expenses of farming is the power cost of pumping water out, so you need to know all of those pieces. But probably for managing in real time, the most important thing is what water is being taken out, what water is leaving the system. That’s why we focused first on ET. There are other efforts on each of the other three legs of the stool, but this is one where we thought, we’re going to get the most bang for the buck most quickly.”

“Compared with the other California state uses of Delta water, do you know off the top of your head a rough estimate of how much is pumped out of the Delta in terms of acre-feet so that we can have a comparative statistic for these numbers?” asked Mr. Gatto.

“Compared with the other California state uses of Delta water, do you know off the top of your head a rough estimate of how much is pumped out of the Delta in terms of acre-feet so that we can have a comparative statistic for these numbers?” asked Mr. Gatto.

“That varies a lot by year, and in the years of this study, like 2015, it was a very a small amount,” said Mr. George. “Since the advent of the SWP, I’m guessing that 2015 is among the lowest export periods. Those are junior water rights and the State Board limited them to health and safety purposes. We were all focused on making sure we kept the aqueduct wet, because we knew that if it dried out, bad things would happen, and there’d be serious problems with infrastructure. It was obviously a dry year for anybody who was dependent on water use south of the Delta.”

“We have had meetings where people express the opinion that the exports, particularly in drought years like 2015, the exports are what have really affected the water level, salinity, but given 1.45 MAF, that’s about double what we thought it was,” said Mr. Gatto. “It goes to show that a lot of that water is being used by agriculture right there.”

“The projects are, in addition to their exports, responsible for maintaining low enough salinity in the Delta for all beneficial uses, so a lot of what was happening in 2015 was that precious previously stored water in reservoirs was released specifically for the purpose of maintaining the water quality in the Delta,” said Mr. George.

“2015 was the fourth year of a drought, and the combined SWP and CVP exports for that year were 1.6 MAF; however, that was an unusually dry year,” offered Executive Director Jessica Pearson. “Sometimes the combined exports are more on the order of 4 MAF, especially because it looks like from year to year, the in-Delta consumption of 1.4 MAF doesn’t change much.”

“It is difficult to make significant changes in water use in the Delta, because it’s a low point in the system that is always wet,” said Mr. George. “It is not clear, for instance, that if you take a field that was in tomatoes and fallow it, that you save much water. As Dr. Medellin said, we have a study going the current agricultural season, where we’re comparing on an apples-to-apples basis, a fallowed field to a cropped field at various elevations in the Delta with different soil types and different weather conditions to figure out how much water you could really save by fallowing a field. If you simply abandon a field, that field is going to ET probably more water than in a managed agricultural setting, so I don’t think, not just based on this study but in general, that there is much water at stake within the Delta agricultural sector. There’s a lot to be done with how that water is managed, but we shouldn’t think that we could reduce agriculture significantly in the Delta and save water for another purpose. That is probably not possible.”

Councilmember Maria Mehranian said, “This study was illuminating for me, to know that consumptive use, a good portion of it, is not for agriculture. That’s a huge finding, in terms of policy … “

Councilmember Maria Mehranian said, “This study was illuminating for me, to know that consumptive use, a good portion of it, is not for agriculture. That’s a huge finding, in terms of policy … “

“It was for me, too,” said Mr. George. “I’m a lawyer, not a scientist. I learned an enormous amount from this study, but probably 30% of total ET, water leaving the black box, is from non-agricultural purposes, and that’s important as we look forward to restoration in the Delta. We are undoubtedly going to be taking some ag land out of agricultural production and putting it into a ecosystem restoration function, and that may take more water.”

Josue Medellin-Azuara added, “If you see in the summary of the report, we have a slightly less consumptive use in 2016 than in 2015. That reinforces Michael’s point in that there’s availability of water in the Delta to divert for crops; however this slight reduction in consumptive use in a more wetter year, which was 2016, is a matter of land use change. Some decisions on idle lands, some decisions on planting new orchards, and some of those things have more of pronounced influence on that. On average, a crop in the Delta uses about 3 feet in consumptive use, and that doesn’t change between the two years, between the wet and dry years. They are virtually the same.”

Councilmember Ken Weinberg noted that urban water agencies have to measure their water use; trying to measure ag water use is the bar that is set. Michael George said that the implementing regulations for SB-88, the legislation to measure water use, were adopted by the State Water Board and things are definitely moving in that direction.

Councilmember Ken Weinberg noted that urban water agencies have to measure their water use; trying to measure ag water use is the bar that is set. Michael George said that the implementing regulations for SB-88, the legislation to measure water use, were adopted by the State Water Board and things are definitely moving in that direction.

Councilmember Ken Weinberg acknowledged it’s not easy. “Agriculture statewide, that’s the bar, which is a much lower bar than urban California has to meet. … I am stunned by the results that you’re getting. What you’re hearing from urban people is that we bear the brunt of shortages; we bore the brunt of those shortages along with the agricultural areas south of the Delta. What this tells me is that Delta agriculture is indifferent to shortages. It doesn’t matter what the hydrologic conditions are. In fact, they are consuming the same amount of water, whether we’re in the worst drought in recorded history in California, or it’s a normal year. To us, San Diego County agriculture faced 30% cutbacks in 2009, and so that’s the constituency we represent. … Usually in a shortage, the byword is share the pain, there is no sharing of anything here, and frankly, I didn’t realize it was this bad.”

“There is no right to waste water in California, that is constitutionally prohibited,” said Mr. George. “And yet, I do think it is really important for all Californians to understand the hydrological challenges in the Delta. It’s a wicked challenge in lots of different ways. We’ve got a system that is highly engineered, and that engineering was the result of governmental policies to reclaim land for agricultural purposes and to tame the swamp and so forth. Some of the impacts of those private decisions made to implement government policy are exactly what we’re dealing with today. Nobody has a right to waste water, but the law of California is that riparian has the right to put to beneficial use the natural flow in the watercourse that goes by that property. That may be a great policy or a poor policy; I happen to think that one of the real problems in California water is that we overlaid a riparian system on an appropriative system, and we’ve never faced the consequences of that. We’re facing it now; we faced it in 2015, and we couldn’t do anything about it. So there are some real important issues that need to get sorted out. People in the Delta who have made investments to carry out policy to create agricultural land and have riparian water rights, and as the Delta Watermaster, all I do is make sure that they are being put to beneficial use. I don’t have any authority beyond that.”

Chair Randy Fiorini then weighed in from the perspective of agriculture. “The Delta is unique, and the fact that there are very few metered siphons in the Delta is because they siphon water out of the Delta, and most of California agriculture receives through groundwater pumping or through gravity deliveries,” he said. “In my case, I have every pump metered because it’s part of my irrigation management process with microsprinkler and drip irrigation. But when you’re furrow and flood irrigating using siphons, it’s a much different scenario. I don’t want anybody to leave here thinking that water in the Delta for agricultural purposes is wasted; it’s not. They are producing food, they are producing food for the dairy industry, they are producing food for humans, and some of that is exported all over the world. It’s a water rights issue. They have a right to the water that passes by those siphons, so I want to make sure we’re clear on how the Delta functions.”

Chair Randy Fiorini then weighed in from the perspective of agriculture. “The Delta is unique, and the fact that there are very few metered siphons in the Delta is because they siphon water out of the Delta, and most of California agriculture receives through groundwater pumping or through gravity deliveries,” he said. “In my case, I have every pump metered because it’s part of my irrigation management process with microsprinkler and drip irrigation. But when you’re furrow and flood irrigating using siphons, it’s a much different scenario. I don’t want anybody to leave here thinking that water in the Delta for agricultural purposes is wasted; it’s not. They are producing food, they are producing food for the dairy industry, they are producing food for humans, and some of that is exported all over the world. It’s a water rights issue. They have a right to the water that passes by those siphons, so I want to make sure we’re clear on how the Delta functions.”

“The Watermaster office was created in 2009 legislation following dry years in 07, 08, and 09 and a concern by upstream diverters that Delta water users were partaking of stored water, that they were extending their water use beyond what their rights allowed them,” continued Mr. Fiorini. “I think it is fair to say that the genesis of this study was because of that expressed concern, so the question is how will the results of this study help to better determine whether water rights are being appropriately utilized in the Delta, or if there is stored water that is being used.”

“What I was trying to get at was in a shortage, to be indifferent to the rest of the state or to used stored water coming downstream, to not make management decisions or look at what are they doing on-farm to be efficient,” said Mr. Weinberg. “We all need to be efficient. Agriculture has to be efficient, and if you’re indifferent to statewide shortages … you don’t have the right to not be efficient. … “

“I can assure you that Delta agriculture is not indifferent to conservation or efficiency,” said Mr. George. “In 2015; we had voluntary agreements in the Central and South Delta that resulted in an overall 30% reduction in diversion for agricultural purposes. We had a lot of fallowed land because people recognized that even if they had the water right, the system was in shortage and they needed to leave water in the system to keep it healthy. I will also point out that there is a tremendous movement toward drip irrigation and other water saving methods. Not just to save water, but also because it improves yield and improves the value of for instance a tomato contract, so I wouldn’t want to leave anybody with the impression that agriculture in the Delta is either indifferent to shortage when it occurs or wasting water or refusing to invest in better crop per drop.”

“One thing that doesn’t make sense,” said Mr. Fiorini. “We had the voluntary agreement to reduce water demand fallowing ground in 2015, but the numbers in consumptive use don’t reflect that there was any change.”

“What was done voluntarily in 2015 was to reduce diversions, but you’re right, it does not appear to have had a measurable effect on ET,” said Mr. George. “Part of that is, alfalfa. It’s like your lawn. If you give it a lot of water, it grows fast; you can cut it more often, make more money. If you starve it for water, it doesn’t die; it grows less quickly but it still ETs water that’s available, maybe water from the underground water table, because if you have a four or five year old alfalfa crop, it’s roots are deep enough to probably intercept the groundwater. And there’s no practical way to cut that off.”

“What was done voluntarily in 2015 was to reduce diversions, but you’re right, it does not appear to have had a measurable effect on ET,” said Mr. George. “Part of that is, alfalfa. It’s like your lawn. If you give it a lot of water, it grows fast; you can cut it more often, make more money. If you starve it for water, it doesn’t die; it grows less quickly but it still ETs water that’s available, maybe water from the underground water table, because if you have a four or five year old alfalfa crop, it’s roots are deep enough to probably intercept the groundwater. And there’s no practical way to cut that off.”

“That’s one of the reasons, though, that we’re doing the study that we’re doing this year to compare 7 different paired sets in the Delta, a fallowed piece of ground next to a cropped piece of ground, to figure out what the savings are,” continued Mr. George. “But remember, if you simply say ‘stop using that water for agricultural purposes’, that’s got some impact on what happens with the yield, but it may not have significant impact on what happens to ET, because if you get weeds, or if you don’t have an economic reason to drain the land and it returns to swamp, you could have an increase in water use. The biggest reason that agricultural water use seems to have gone down in 2016 compared to 2015, doesn’t have much to do with the application of water one year to the next; it’s what Dr. Medellin said. It’s people who fallowed ground, took land out of production, so that they could plant almonds. That had an impact in reducing water use on that field in 2016 versus 2015 without regard to what was going on hydrologically in the system, but it also hardened the demand, and that demand will go up as those trees mature. So understanding those implications of private activity with senior water rights in a place like the Delta, it’s complicated.”

“It’s complicated,” said Mr. Fiorini. “That’s a good message to end on.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION …

- Read the report here: A Comparative Study for Estimating Crop Evapotranspiration in the Delta

- For the agenda, meeting materials, and webcast link, click here.

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!