In 2016, Governor Brown signed Assembly Bill 1755, the Open and Transparent Water Data Act, which requires the Department of Water Resources, in consultation with the California Water Quality Monitoring Council, the State Water Resources Control Board, and the Department of Fish and Wildlife to improve the accessibility and usability of water and environmental data. The intended outcome for AB 1755 is to create, operate, and maintain a statewide integrated data platform that is operational with available water and environmental State agency datasets by Sept 1, 2019.

Many organizations now make scientific data available on their organizational website, or through data portals maintained and managed by government agencies, university libraries, non-profit organization or other venues. Nonetheless, many obstacles remain, which make it difficult to organize, locate, and access scientific data from the many organizations that collect these data.

Science governance – in particular how policymakers get from data to decisions – is an area of increasing interest in the Delta, and to help increase understanding of science governance and the data to decision-making process, Delta Stewardship Council staff will provide an overview of a key component of the process at each Council meeting from May to September 2018.

The first presentation in the series focuses on data and how state agencies are working to implement AB 1755. George Isaac, Senior Environmental Scientist with the Delta Stewardship Council, noted that the Delta Science Program organized a data summit in 2014 which brought scientists, resource managers, decision makers, academia stakeholders, and trusted citizens together to discuss a new era in information management and knowledge discovery and how applications of this knowledge can apply to complex environmental policy and management decisions.

The summit was followed up by production and publication of a white paper entitled, Enhancing the Vision for Managing California’s Environmental Information, which was instrumental in the development of the bill, AB 1755, the Open and Transparent Water Data Act. The legislation called for developing a system for water and ecosystem data generated in the Delta region that will be accessible, transparent, and interoperable in a standard format for agencies, managers, stakeholders, and citizens.

The summit was followed up by production and publication of a white paper entitled, Enhancing the Vision for Managing California’s Environmental Information, which was instrumental in the development of the bill, AB 1755, the Open and Transparent Water Data Act. The legislation called for developing a system for water and ecosystem data generated in the Delta region that will be accessible, transparent, and interoperable in a standard format for agencies, managers, stakeholders, and citizens.

“This is important because increased access to data will support better informed decisions and cost-effective investments,” said Mr. Isaac. “Second and equally important, the implementation of the Delta Plan is dependent on data that is easily accessible from various sources and is crucial in addressing adaptive management and the coequal goals.”

On the panel to discuss the implementation of AB 1755 was Christina McCready, Chief of the Integrated Data and Analysis branch with the Department of Water Resources; Greg Gearhart, Deputy Director of the Office of Information Management and Analysis at the State Water Board, and Tom Lupo, Deputy Director of Data and Technology for the Department of Fish and Wildlife.

CHRISTINA McCREADY: DWR meeting deadlines, forging ahead on implementation

Since AB 1755, the agencies have been working hard to make progress towards the requirements of the bill, but also to embrace the spirit of the bill and reach beyond that, said Christina McCready. The legislation had some deadlines which came very quickly: By January 2018, they were to produce a strategic plan and protocols.

Since AB 1755, the agencies have been working hard to make progress towards the requirements of the bill, but also to embrace the spirit of the bill and reach beyond that, said Christina McCready. The legislation had some deadlines which came very quickly: By January 2018, they were to produce a strategic plan and protocols.

“The strategic plan in the legislation was aimed at managing data for transparency and openness; the protocols were aimed at allowing data to be shared more meaningfully,” she said. “We have embraced that and have tried to reach past that.”

The next deadline was an option by April 1, 2018 to issue a Request for Proposal for the development or the building of a platform, but because the Department is leveraging existing tools, they did not see a need to bring on consultants in that way, she said. The final two deadlines are September 2019, and August of 2020; by that time, they are supposed to have made available certain datasets that are described in the legislation as they are available and ready to share; and those are to be updated quarterly thereafter.

She presented a graphic that depicted the implementation process using puzzle pieces; the blue puzzle pieces are the requirements placed on state agencies. The strategic plan was released in January 2018; the plan articulates a number of goals in the context of data availability and data management.

She presented a graphic that depicted the implementation process using puzzle pieces; the blue puzzle pieces are the requirements placed on state agencies. The strategic plan was released in January 2018; the plan articulates a number of goals in the context of data availability and data management.

“We have articulated a vision that really aims at something I’m sure is near and dear to you: useful data for sound, sustainable water resource management,” she said. “It’s a simply stated vision, not necessarily simply attained. In that spirit, we then have articulated a need for data to be sufficient to support water resource management and answer water resource related questions; that data are accessible meaning available for use and discoverable; that data are useful and by that we mean they are available in a form that facilitates use in different models, visualizations, and reports; and finally that they are used. If we have all this data and we don’t use it, we might as well not have it.”

The legislation also required that protocols be developed; Ms. McCready said that these initial protocols are very low threshold, but the protocols themselves will be a living document. “We hope all folks who want to make data available or are obligated to make data available will be able to reach these as a threshold,” she said. “As we move on, we may offer some more advanced protocols or more rigorous protocols, and recognizing that change comes over much time, if it’s going to be successful, we expect to emphasize more of a best practice approach so that we can allow people to mature with us.”

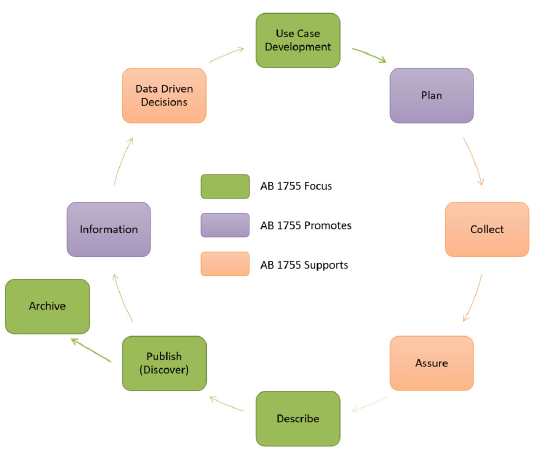

For the data to be useful, the system must be developed with the end user in mind, and so part of the implementation of AB 1755 involves examining use cases. The UC Berkeley Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment released a report, Data for Water Decision Making, which makes a case for anchoring the development of data systems in the needs of end users; the report describes the lessons learned from a process of stakeholder engagement focused on defining and clarifying uses of water data, and how knowledge of these uses can inform the development of water data systems.

For the data to be useful, the system must be developed with the end user in mind, and so part of the implementation of AB 1755 involves examining use cases. The UC Berkeley Center for Law, Energy, and the Environment released a report, Data for Water Decision Making, which makes a case for anchoring the development of data systems in the needs of end users; the report describes the lessons learned from a process of stakeholder engagement focused on defining and clarifying uses of water data, and how knowledge of these uses can inform the development of water data systems.

Ms. McCready said that one way to describe a use case is that it’s a short discussion of who needs what data in what form for what decision. “I think of a use case as sort of a common meeting space between those folks who are extremely knowledgeable and very close to the decisions about water management and a meeting place with those folks who are maybe more technical minded, either data collectors or IT professionals,” she said. “All of these folks are experts in their own fields, but the use case provides sort of the common meeting ground for that conversation to be meaningful.”

The goal wasn’t just to have a website with a bunch of links on it; they want to have the user in mind from the beginning, so they are considering what kinds of questions people are trying to answer, what kind of data and in what form is that data necessary to help answer that question, and who needs the information. “We’re looking at it from that perspective and by making the user the focal point, we hope that the system will be that much more usable, which goes towards goals and our ultimate vision of useful data for sound, sustainable water resource management,” she said.

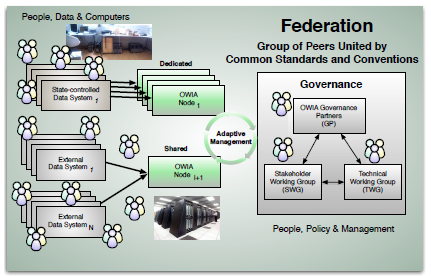

The OWIA or Open Water Information Architecture recommendations were attached to the protocols document that came out in January; the document lays out some of the functional requirements, what’s expected of the system, what is a user expecting it to do, and technical requirements. “It’s very brief, extremely dense, and it’s essentially the beginning of a pathway towards this strategy of federation,” she said.

The OWIA or Open Water Information Architecture recommendations were attached to the protocols document that came out in January; the document lays out some of the functional requirements, what’s expected of the system, what is a user expecting it to do, and technical requirements. “It’s very brief, extremely dense, and it’s essentially the beginning of a pathway towards this strategy of federation,” she said.

Data federation is a form of data management where the data is stored in a number of different places, but is made accessible as one integrated data source by using on-demand data integration. Ms. McCready likened it to using a library card catalog, whereby looking under different authors or different search terms, you become aware of other materials of interest, and you might be able to access them through an interlibrary loan system.

“What we aim to do is to emphasize federation as opposed to co-location,” she said. “We’re not trying to make one big castle of data that everybody can pull from. Instead, what we’d like to have is existing portals and platforms work together, so that a user might enter one and be able to discover what’s available on another. In addition to saving us a lot of building time and building money, it also allows people to join voluntarily, so if a person who operates a portal or platform outside of the state agencies that are implicated in AB 1755, they might choose to honor the protocols and observe some of the best practices we’ve put forward, and in so doing, make their data available, accessible, and discoverable.”

“What we aim to do is to emphasize federation as opposed to co-location,” she said. “We’re not trying to make one big castle of data that everybody can pull from. Instead, what we’d like to have is existing portals and platforms work together, so that a user might enter one and be able to discover what’s available on another. In addition to saving us a lot of building time and building money, it also allows people to join voluntarily, so if a person who operates a portal or platform outside of the state agencies that are implicated in AB 1755, they might choose to honor the protocols and observe some of the best practices we’ve put forward, and in so doing, make their data available, accessible, and discoverable.”

Data challenges are opportunities for interested parties to get into the data and figure out what problems they can solve or what visualizations they can create for decision makers. “The data challenge is really an opportunity for people to address a specific problem or set of problems using data and showing some level of innovation that gets the state farther or the host farther,” she said.

The test bed concept is much like a sandbox, which is a place where people can experiment but not affect the system itself. “The idea behind a test bed is that we might similarly issue a charge to people who are excited, interested, and innovative and ask them to test perhaps taking a use case from beginning to end and figuring out where the problems are,” she said.

The final puzzle piece is about exploration of governance and funding; Ms. McCready acknowledged the energy and interests from other sectors, and that philanthropy helped to underwrite and manage a contract with Redstone Strategy Group, who produced the report, the Internet of Water. “That’s a national level version of this conversation where there’s a look at how we make data more meaningful and how we allow it to play a bigger role in science and management of water resources,” she said.

The final puzzle piece is about exploration of governance and funding; Ms. McCready acknowledged the energy and interests from other sectors, and that philanthropy helped to underwrite and manage a contract with Redstone Strategy Group, who produced the report, the Internet of Water. “That’s a national level version of this conversation where there’s a look at how we make data more meaningful and how we allow it to play a bigger role in science and management of water resources,” she said.

“So these are the puzzle pieces that constitute our AB 1755 implementation,” she said. “We’re working together to plan specific projects and we ultimately soon be testing the federation and interoperability of data on the existing portals.”

She concluded by noting that the California Government Operations Agency operates a portal at www.data.ca.gov which already has many datasets, including many from the State Water Resources Control Board; more recently, the California Natural Resources Agency recently made their data available and in particular, a lot of fisheries and ecological data from the Department of Fish and Wildlife.

GREG GEARHART: Liberating data at the State Water Board

Greg Gearhart, Deputy Director of the Office of Information Management and Analysis, described his job as the ‘chief data liberator’ for the State Water Board. “I’m often at odds with people who want to hold onto their data and keep it in a protected mode, whether it’s internal or external parties,” he said. “That’s one of the challenges of open data; it really is something that transcends the statute, going back to prior administrations and the federal government and European Union, about the mid-2010 era, when there was an effort to make government more open using techniques that were available in the retail consumer side of the data world … the vision was to make government also accessible in the same manner, so this is the movement toward that accessibility.”

In some ways, this is easy for the Water Board as their organization is based on public involvement. They have a public process, they are used to producing their information and showing their work on their products, so a lot of that shift came relatively easy; what is not easy is the technology and the infrastructure work to get this data to show up at that accessible layer.

In some ways, this is easy for the Water Board as their organization is based on public involvement. They have a public process, they are used to producing their information and showing their work on their products, so a lot of that shift came relatively easy; what is not easy is the technology and the infrastructure work to get this data to show up at that accessible layer.

“So, using the metaphor of the library, we’re trying to build delivery trucks that provide useful information so that datasets that show up at that front door,” he said. “So we’re using the Gov Ops, the State of California’s open data platform, and we were using that prior to the statute. It actually helps to have two systems in California government that are producing published open data sets as it can provide interoperable tests and federation tests within our own environment.”

Mr. Gearhart said the Water Board has a number of useful datasets and they’ve been working to deliver that data to the platform, but the hard work of converting datasets and getting stakeholders within the Water Board is taking a lot of time. The purpose of the statute focuses more on water markets, how much water is being used and for what purpose, and similar types of data, so they are focusing on those and prioritizing building infrastructure to deliver pipelines of that kind of that data to an open data publishing platform.

The other benefit of making the data available is encouraging people to use the data in ways that provide new insights or provide operational tools that don’t exist today, so they have run a number of open data challenges. “One of them produced an insight about water conservation and the water energy savings associated with water conservation that sort of changed conversation in policy,” Mr. Gearhart said. “The other one provided an interesting operational tool that looked at when and how you might want to operate releases from reservoirs so you could optimize your desire, whether that was improving habitat for juvenile salmon, or what have you; you could look at data that had groundwater elevation, are the fish in the traps, what is the release, what are the other pressures in the system, and you could provide a tool that helps operational decisions.”

The other benefit of making the data available is encouraging people to use the data in ways that provide new insights or provide operational tools that don’t exist today, so they have run a number of open data challenges. “One of them produced an insight about water conservation and the water energy savings associated with water conservation that sort of changed conversation in policy,” Mr. Gearhart said. “The other one provided an interesting operational tool that looked at when and how you might want to operate releases from reservoirs so you could optimize your desire, whether that was improving habitat for juvenile salmon, or what have you; you could look at data that had groundwater elevation, are the fish in the traps, what is the release, what are the other pressures in the system, and you could provide a tool that helps operational decisions.”

“These are the benefits that we see coming out of open data and so we’re doing a lot of work to build that infrastructure and then sort of generate interest on the external side to help activate the right datasets arriving at the library,” he concluded.

TOM LUPO: Department of Fish and Wildlife, the single largest collection of data in the state

Tom Lupo is the Deputy Director of Data and Technology for the Department of Fish and Wildlife; he described his position as chief data wrangler or data liberator for the Department. He began by saying that when AB 1755 came along, requiring them to develop open data, distribution channels, and platforms, the Department was immediately on board. “We’ve been in this business for a very long time, and as a regulatory agency, the Department of Fish and Wildlife has already put a premium on transparency,” he said. “We need to make our data that drives decision making open and available to all eyes who want to see it.”

Back as early as the 1970s, the Department of Fish and Wildlife was charged with developing and aggregating databases regarding endangered species and significant natural areas, and that data has always been open and available to anyone who wants it, he said. Since around 2000, they have had an open platform called BIOS which offers close to 2500 different data layers. The data include data aggregated from others and data that has been contributed to them, as well as pretty much all the data produced within the Department.

Back as early as the 1970s, the Department of Fish and Wildlife was charged with developing and aggregating databases regarding endangered species and significant natural areas, and that data has always been open and available to anyone who wants it, he said. Since around 2000, they have had an open platform called BIOS which offers close to 2500 different data layers. The data include data aggregated from others and data that has been contributed to them, as well as pretty much all the data produced within the Department.

“I think it’s fair to say that represents the single largest collection of data of any state agency in California – at least within the environmental realm,” said Mr. Lupo. “We are more than happy to provide that data to the folks who are putting together the portal for the Delta, and also anything else that falls under AB 1755.”

The term ‘water data’ to the Department means fish habitat – it’s the fluid habitat that the fish live in, so the focus of their work for this project are fish, currents, distribution, and other ecosystem type data, he said. One of the primary datasets they have is vegetation mapping (or habitat) for the Delta, which has been mapped 3 or 4 times over, so there is a long time series of observed change in habitat and vegetation.

“The Delta is probably one of the most heavily mapped monitored pieces of territory on earth, so we have a lot of data for the Delta,” said Mr. Lupo.

IN CONCLUSION …

Lead Scientist Dr. John Callaway pointed out that a lot of the data that is becoming available will be useful for both the Council and the Science Program. The vegetation mapping data could be useful for some performance measures that involve distribution of different habitats. There is growing interest in integrated modeling, so there is potential for the hydrological data to link to fish data, and some data could be used for calibrating or validating models.

“One of the challenges is integrating across these kinds of datasets, such as being able to link up some of the habitat data or other kinds of data to hydrologic data to water quality data, but I think that is one thing with AB 1755, moving towards an integrated or federated system should facilitate that sort of ability to look across multiple datasets and link across datasets,” he said.

“One of the challenges is integrating across these kinds of datasets, such as being able to link up some of the habitat data or other kinds of data to hydrologic data to water quality data, but I think that is one thing with AB 1755, moving towards an integrated or federated system should facilitate that sort of ability to look across multiple datasets and link across datasets,” he said.

George Isaac concluded the agenda item, saying AB 1755 is a game changer. “It’s going to bring this data together into a format that researchers can understand and can put it together, so knowledge discovery is going to be accelerated in this process,” he said. “That is the exciting part about AB 1755. The technical requirements are going to make all of this data become standard so people can access it in one format and find out the meaning behind it.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION …

- Click here for DWR’s page on AB 1755 implementation.

- Progress Report – Implementing the Open and Transparent Water Data Act with Initial Draft Strategic Plan and Preliminary Protocols

- Data for Water Decision Making – Use Cases

- Open Water Information Architecture (OWIA) Draft

- AB 1755 Fact Sheet

- Aspen Dialog Series – Internet of Water

- California Council on Science and Technology (CCST)

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!