The Epic California Drought as Viewed from Space

Dr. Jay Famiglietti is a hydrologist and a professor of earth system science and of civil and environmental engineering at the University of California Irvine, and the senior water scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology. At the California Irrigation Institute Conference held in January of this year, Dr. Famiglietti gave this keynote presentation, focusing on what the satellites are telling us about the California drought, the implications for sustainability, and the challenge of communicating the seriousness and consequences of the situation.

Dr. Jay Famiglietti is a hydrologist and a professor of earth system science and of civil and environmental engineering at the University of California Irvine, and the senior water scientist at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology. At the California Irrigation Institute Conference held in January of this year, Dr. Famiglietti gave this keynote presentation, focusing on what the satellites are telling us about the California drought, the implications for sustainability, and the challenge of communicating the seriousness and consequences of the situation.

Dr. Famiglietti began by pointing out that there’s a difference between drought and chronic water scarcity. “Drought comes and goes, and this one could be on the way out; it’s hard to know just yet,” he said. “But chronic water scarcity is a persistent state, and that’s what we face here in California.”

SO WHAT ARE THE SATELLITES TELLING US ABOUT THE DROUGHT?

The GRACE mission, the Gravity Recovery And Climate Experiment, was launched in 2002. It has become synonymous with understanding groundwater depletion. Dr. Famiglietti explained how the satellite functions like a scale in the sky: “First of all the satellites are not that big and as they orbit around the earth, they follow each other in a tandem orbit. They are about 400 kilometers up and are separated by 200 kilometers. They orbit over the poles so as the earth spins around, we get this sweeping coverage.”

The GRACE mission, the Gravity Recovery And Climate Experiment, was launched in 2002. It has become synonymous with understanding groundwater depletion. Dr. Famiglietti explained how the satellite functions like a scale in the sky: “First of all the satellites are not that big and as they orbit around the earth, they follow each other in a tandem orbit. They are about 400 kilometers up and are separated by 200 kilometers. They orbit over the poles so as the earth spins around, we get this sweeping coverage.”

“When the satellites encounter a region that has more water mass on the ground, a region that’s gained water weight like the Sierra with all the snow, the tug on the satellites of the gravitational pull is just a little greater than normal, and the satellites get pulled one at a time, just a little bit closer – just like when you step on a scale, if you weigh more, you push the scale down a little more, that’s gravity,” he continued. “Likewise if they fly over a region that’s losing water, like the Central Valley, then that region is losing water weight and the gravitational tug is a little bit less and the satellites float just a little bit higher in their orbit.”

“So by keeping track of the ups and downs and the vertical position of the satellite, that’s really the measurement – the position of the satellites. We can map out earth’s gravity field and from that understand the regions of the earth that are gaining or losing water mass, total water mass. We have to do work to pull out the groundwater part, total amount, the change in the total amount of water stored in a region on a monthly basis.”

“So by keeping track of the ups and downs and the vertical position of the satellite, that’s really the measurement – the position of the satellites. We can map out earth’s gravity field and from that understand the regions of the earth that are gaining or losing water mass, total water mass. We have to do work to pull out the groundwater part, total amount, the change in the total amount of water stored in a region on a monthly basis.”

Dr. Famiglietti had some caveats: It has a low resolution in space and time. It’s looking at regions the size of the Delta watershed – 150,000 square kilometers, so it gives a global picture that is not particularly useful for local water management. However, they are working on downscaling some of that information to make it more useful.

The satellites only measure change in water storage. “The only way to figure out how much groundwater is in the ground and is to go and drill the aquifers, so we’re looking at changes in total water storage,” he said. “If you want to pull off the just the groundwater component, we need to do some research, mainly understand how much soil moisture is there, how much snow is there, how much water is in the reservoirs, and in California we can actually do that pretty well.”

GRACE has been ‘pretty cool’ in terms of the information that it gives us, he said. The mission was launched in 2002, and the satellites are almost dead. It was designed as a five year mission, and the batteries are dying and fuel conditions uncertain, but a follow on mission is in the works. “It is basically exactly the same mission, so we can have continuity,” Dr. Famiglietti said. “We call it a climate continuity mission because not only is GRACE helping us with fresh water on land, but it’s been great for understanding and monitoring the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets melting and ocean mass increases that lead to sea level rise, so it’s really important for monitoring climate. That’s going to launch from Vandenburg in December, 2017, and hopefully then we’ll have a couple more decades of information.”

GRACE has been ‘pretty cool’ in terms of the information that it gives us, he said. The mission was launched in 2002, and the satellites are almost dead. It was designed as a five year mission, and the batteries are dying and fuel conditions uncertain, but a follow on mission is in the works. “It is basically exactly the same mission, so we can have continuity,” Dr. Famiglietti said. “We call it a climate continuity mission because not only is GRACE helping us with fresh water on land, but it’s been great for understanding and monitoring the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets melting and ocean mass increases that lead to sea level rise, so it’s really important for monitoring climate. That’s going to launch from Vandenburg in December, 2017, and hopefully then we’ll have a couple more decades of information.”

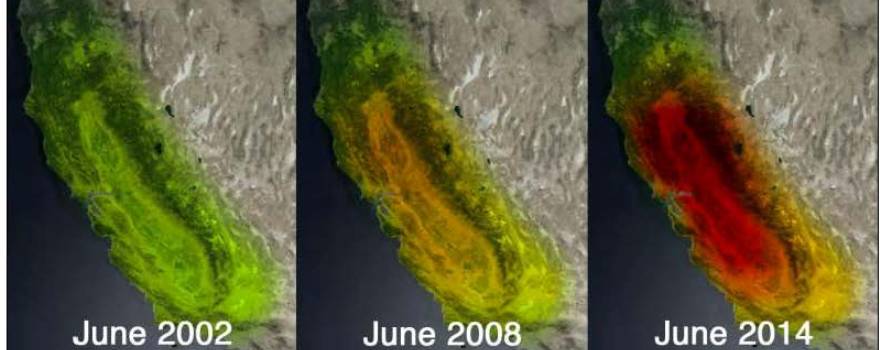

He then played an animation showing the data for California and the west, noting that the blues are wetter than normal, and red is the opposite. “These are monthly data, so we’re looking at the monthly ups and downs of water storage changes across the west,” he said. “When it comes into the current drought, we should see California getting pretty red.”

Drilling down into the data, he then presented a chart for the Sacramento and San-Joaquin River basin including the Central Valley which show the change in total water storage from the start of the mission in 2002 through to August 2016.  The ups and downs show the wet season and dry season; the peaks are at March around the end of the snow season, and the troughs are in November at the end of the growing season.

The ups and downs show the wet season and dry season; the peaks are at March around the end of the snow season, and the troughs are in November at the end of the growing season.

“There are these trends, so we can quantify now, for the first time, what is really happening with the ins and outs of total water storage across the region,” Dr. Famiglietti said. “We can see the dry season is getting drier, and we can start to do things like quantify how much water we’re losing in California during this drought. We nominally say it began in 2011 and that’s 15 cubic kilometers a year or 12 MAF. To put it in perspective, our total domestic and municipal water budget each year for all of California is about 10 MAF, so it’s a big loss.”

“You can start to see these other timescales of the drought, and arguably we could say that we’ve been losing water here for awhile,” he said. “These GRACE data is showing us something we knew but we’re not talking about it and we need to, and that is that we’ve been losing water this whole time. The picture that emerges is that winter rains come and go, but trend is really coming from the disappearance of the groundwater.”

He then presented a chart that is a combination of USGS data and the GRACE-based estimates of groundwater depletion in the Central Valley from 1960 up until the present. The background colors in the chart represent the climate with wetter periods shown in blue and drier periods show in tan. The story here is that California groundwater has been dramatically declining, he said. The story goes back to 1930.

He then presented a chart that is a combination of USGS data and the GRACE-based estimates of groundwater depletion in the Central Valley from 1960 up until the present. The background colors in the chart represent the climate with wetter periods shown in blue and drier periods show in tan. The story here is that California groundwater has been dramatically declining, he said. The story goes back to 1930.

“People keep asking, what about now? Aren’t we going to refill the aquifers? Hell no, because all that happens in the wet periods is we get a little bump. This is our behavior, so we need to embrace this and work with this. Hopefully with SGMA, we could try to level that off, but I don’t think we could ever level it off and have the agricultural productivity that we have, so we have to be thinking about that.”

Turning to subsidence, Dr. Famiglietti presented a slide of the classic Joe Poland picture, describing subsidence as similar to deflating a bicycle tire or car tire; you let the air out of a tire and it flattens out. “Those aquifers have a lot of clay minerals, and it’s just the structure of the clay minerals. They are flat and so they stack up in the ground and the ground subsides,” he said. “The subsidence rates are happening at the fastest they have ever happened, and we’re tracking it now more carefully and there’s not necessarily any slowdown right now. As we track it more carefully, we’re also understanding the behavior of it. And once that storage is lost, it’s gone forever. It’s not coming back.”

Turning to subsidence, Dr. Famiglietti presented a slide of the classic Joe Poland picture, describing subsidence as similar to deflating a bicycle tire or car tire; you let the air out of a tire and it flattens out. “Those aquifers have a lot of clay minerals, and it’s just the structure of the clay minerals. They are flat and so they stack up in the ground and the ground subsides,” he said. “The subsidence rates are happening at the fastest they have ever happened, and we’re tracking it now more carefully and there’s not necessarily any slowdown right now. As we track it more carefully, we’re also understanding the behavior of it. And once that storage is lost, it’s gone forever. It’s not coming back.”

In the first half of the drought, 2007 to 2011, subsidence rates were about 2 to 4” per year, but in the real thick of the drought, the growing season of 2014, it was up to 1.5 to 2” per month, so that’s a foot and a half to two feet per year, he said. He noted that the latest assessment has the numbers in some spots up over a meter per year.

“You know that’s not good, so we photoshopped Joe to show the total amount of subsidence … “

“You know that’s not good, so we photoshopped Joe to show the total amount of subsidence … “

Dr. Famiglietti then turned to the Colorado River basin, presenting a chart showing the GRACE trends from 2005 to 2014. “It’s looking at ups and downs, but the trends – we wanted to know where’s that trend coming from. We specifically wanted to know because we spend so much time managing surface water and not groundwater, what was happening with the groundwater. … I think this really indicates the need for conjunctive surface and groundwater management, and what happens when we don’t do that. We’re losing groundwater across the basin at a rate of 6 or 7 to 1, and so if the groundwater is our saving account, we’re managing the checking account here, and turning a blind eye to the retirement account.”

He then presented a map showing groundwater depletion for the United States, noting that blues are getting wetter, red is getting drier. The hot spots in the country are the depletion of the southern half of the Ogallala, the depletion of the Central Valley groundwater, and the glaciers melting up in Alaska; the upper half is getting wetter. “There are issues here about haves and have nots and social equity and where we going to have agriculture in the future – are people and farms moving? Some people are actually moving to the places that are a little bit wetter, and as the climate warms, some of these regions will be a little bit wetter, so there’s a future here that I think we should be concerned about.”

He then presented a map showing groundwater depletion for the United States, noting that blues are getting wetter, red is getting drier. The hot spots in the country are the depletion of the southern half of the Ogallala, the depletion of the Central Valley groundwater, and the glaciers melting up in Alaska; the upper half is getting wetter. “There are issues here about haves and have nots and social equity and where we going to have agriculture in the future – are people and farms moving? Some people are actually moving to the places that are a little bit wetter, and as the climate warms, some of these regions will be a little bit wetter, so there’s a future here that I think we should be concerned about.”

IMPLICATIONS FOR SUSTAINABILITY

“We’re in a state of chronic water scarcity,” Dr. Famiglietti said. “We use more water than is available to us on an annual renewable basis, and most of that is used to make up the difference from the savings account for groundwater. So we’re not living on our income; we’re blowing the future – and it’s time for us to manage the future.”

“We have agricultural productivity, and I’m not here to say we should cut back. I like to eat. But in contrast to the drought, there’s no end in sight. There are lots of sustainability solutions for metropolitan regions like desalination and sewage recycling, but that’s not enough water for agriculture, so we use too much so we need to do some things. Conservation, efficiency, pricing, innovation, whatever – everything should be on the table.”

“Either we’re going to move water to California or the agriculture will move out, so we need to be thinking realistically about that,” he said.

“We’re not alone,” Dr. Famiglietti said. “This is happening all over the world. Here’s a map of the 37 biggest aquifers that was published in 2015 in Water Resources Research; it shows that over half of the world’s major aquifers are past sustainability tipping points. They are being depleted, some of them very rapidly. And those all support the world’s major food producing regions. So the water, food, and energy nexus is very, very real.”

“We’re not alone,” Dr. Famiglietti said. “This is happening all over the world. Here’s a map of the 37 biggest aquifers that was published in 2015 in Water Resources Research; it shows that over half of the world’s major aquifers are past sustainability tipping points. They are being depleted, some of them very rapidly. And those all support the world’s major food producing regions. So the water, food, and energy nexus is very, very real.”

“There are real threats to global food security,” he continued. “I’ve been saying this for awhile, but no one’s listening. Maybe this crowd will. Given that California grows food for the nation, isn’t it time for us to be thinking about this California problem as a national problem? If we want to sustain agriculture at its scale in California, we’re killing ourselves try to it just with California water, so that’s a message that we need to talk about and get out there.”

What about the implications for SGMA – what does sustainability really mean in a chronically water scarce food producing state? “I don’t think we’re going to level off those trends, but I think we need to manage the rate at which we are using the groundwater,” Dr. Famiglietti said. “There are so many unknowns that are impediments to moving towards sustainability. We don’t really know how much water we have. We don’t. We don’t how much water is in the aquifer system that underlies the Central Valley.”

“We don’t really understand how much water we need, we don’t really know how much water we need to save and use for the environment – we just haven’t done that work,” he continued. “We’re only starting to understand how these are changing. The supply versus the demand, how are they going to change over time with climate change, with population growth, with more conservation and more desal, with more efficiency.”

Dr. Famiglietti reminded that these are just his opinions. “This is not what NASA says, this is me, a professor who has been working on this for many, many years. The time to move towards conjunctive surface and groundwater management is probably now, given that we’re forming the Groundwater Sustainability Agencies and each agency has to produce a groundwater sustainability plan. You can’t have sustainability with just focusing on surface water and not groundwater, or on groundwater and not surface water; we have to be doing these things together.”

Science-driven scenarios are essential, he said, presenting a graph from a paper from the last class he taught at UCI. “Scientists like myself need to provide to stakeholders and to decision makers science based alternatives. This is just an example. On the left of the chart are the observations that I showed you, the dots showing the long-term groundwater depletion from the USGS. The solid black line is a model. It goes up to the present, and now we need to be able to share with you what happens is we do nothing. Well, we’re going to hit the bottom. What happens if we all move away, things would be great. What happens if we do 20% increases in efficiency and so on. This is more of a concept, not actual numbers that we want to share with you and say this is a scenario. We are obviously working on this stuff.”

Science-driven scenarios are essential, he said, presenting a graph from a paper from the last class he taught at UCI. “Scientists like myself need to provide to stakeholders and to decision makers science based alternatives. This is just an example. On the left of the chart are the observations that I showed you, the dots showing the long-term groundwater depletion from the USGS. The solid black line is a model. It goes up to the present, and now we need to be able to share with you what happens is we do nothing. Well, we’re going to hit the bottom. What happens if we all move away, things would be great. What happens if we do 20% increases in efficiency and so on. This is more of a concept, not actual numbers that we want to share with you and say this is a scenario. We are obviously working on this stuff.”

THE COMMUNICATIONS CHALLENGE

It’s tough to get this information out, acknowledged Dr. Famiglietti. “I used to think this: Once people truly understand the sources of their water supply and how they are changing, meaning – where your water comes from, how much are you getting from the Sierra, how much from snowmelt, how much from groundwater, how much from the Colorado River basin – if people understand that, and look at the mountains over the past 5 years, some with no snow, they realize that we have no water, and acceptance of the need for protection and action is far more likely. That was my working hypothesis for many years, so this is explaining where does your water come from, the snow, the groundwater, surface water, and how it might be changing over time.”

Dr. Famiglietti then played a clip from “The Last Call at the Oasis”

“I’ll end it there,” he said. “We really need to work together to elevate these critical water issues, now more than ever, to the level of everyday understanding.”

“Thank you.”

For more information …

Coming tomorrow …

- More from the California Irrigation Institute Conference: A panel on how Groundwater Sustainability Agency formation is progressing around the state.

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!