‘Normative science’ has a corrosive effect on the entire scientific enterprise, says Dr. Robert Lackey

These days, scientists in environmental science, natural resources, ecology, conservation biology, water resource management, and similar disciplines are often not trusted by the public and decision-makers to present policy-neutral science. One reason is that scientists advocating personal or organizational positions on ecological and environmental policy issues has become widely tolerated as acceptable professional behavior and is even encouraged by a segment of the scientific community, and as a result, the scientific enterprise is collectively slipping into a morass that risks marginalizing the contribution of science to public policy, says Dr. Robert Lackey.

Public confidence that scientific information is technically accurate, policy relevant, and politically unbiased is central to informed resolution of policy and regulatory issues that are often contentious, divisive, and litigious. Dr. Lackey warns that scientists should watch for the often subtle creep of normative science (i.e., information that appears to be policy neutral, but contains an embedded preference for a particular policy or class of policies). Failing to do so risks marginalizing the essential role that science and scientists ought to play in informing decisions on important public policy questions, he maintains.

Dr. Robert Lackey is professor of fisheries science at Oregon State University. In 2008 he retired after 27 years with the Environmental Protection Agency’s national research laboratory in Corvallis where he served as Deputy Director and Associate Director for Science, among other senior science and leadership jobs. His professional assignments involved diverse aspects of natural resource management, but mostly he has operated at the interface between science and policy. In this webinar presented to the American Water Resources Association in May of 2016, he talked about use and misuse of science in water resource policy and management.

Here’s what he had to say.

Dr. Bob Lackey began by discussing his background. “The first phase of my career started pretty much in science research,” he said. “I found this to be comfortable, it was understandable, and the rules were clear cut: you did your research, and perhaps you published peer reviewed literature, and things were pretty good. Not a lot of controversy; I certainly had to hustle for money and so forth, but generally speaking, it was fairly straightforward.”

As his career grew, he became more involved at interface with policy people, and so the second phase of his career was essentially interacting and being a science interface with policy makers, policy analysts, political people, and the people who make decisions. “To me as a hard core scientist, this was a scary world, but it was fascinating,” he said. “I learned an awful lot, and I did that for quite a few years and found it to be quite enjoyable, but frustrating in many areas and in many situations. The third phase of my career was going back to academia which is where I’m at now at Oregon State University, and this afforded a time to kind of analyze and reflect. So when I was asked to present some comments, my question essentially was, what about insights that I learned in my career that might be useful to other people about the use and abuse of science, and so that’s what you’re going to hear today.”

“In my view, in the water resource management, natural resource management, and similar kinds of fields is that the misuse of science has become increasingly common,” he said. “Over my career, I’ve seen it increase in misuse, and I think this has undermined the confidence that people have – the public, the decisionmakers and the policymakers – in the entire scientific enterprise, so this is my take home message. The rest of my comments are essentially going to be a roadmap to how I got to this conclusion.”

“In my view, in the water resource management, natural resource management, and similar kinds of fields is that the misuse of science has become increasingly common,” he said. “Over my career, I’ve seen it increase in misuse, and I think this has undermined the confidence that people have – the public, the decisionmakers and the policymakers – in the entire scientific enterprise, so this is my take home message. The rest of my comments are essentially going to be a roadmap to how I got to this conclusion.”

Science is information gathered in a rational, systematic, testable, and reproducible manner. “Science or the scientific method is how you arrive at the information; science is just simply information,” he said. “But science has those four characteristics: if it doesn’t have all four characteristics, it’s still information, but it’s not science as we traditionally use it. It’s rational, it’s not faith based, it does not require basically any orders from anybody else that you take on faith; it’s systematic, that is it’s logical; it’s testable, that is other people can take measurements and can come up with the same general conclusions that you do; and it’s reproducible. That is, if other people follow your methods and your procedures, they’ll come up with the same answer within a range of error and of course if they don’t, then that means the scientific conclusion, the information hasn’t been confirmed, and you go back to the drawing board and come up with a new hypothesis. That’s the scientific method.”

Science is information gathered in a rational, systematic, testable, and reproducible manner. “Science or the scientific method is how you arrive at the information; science is just simply information,” he said. “But science has those four characteristics: if it doesn’t have all four characteristics, it’s still information, but it’s not science as we traditionally use it. It’s rational, it’s not faith based, it does not require basically any orders from anybody else that you take on faith; it’s systematic, that is it’s logical; it’s testable, that is other people can take measurements and can come up with the same general conclusions that you do; and it’s reproducible. That is, if other people follow your methods and your procedures, they’ll come up with the same answer within a range of error and of course if they don’t, then that means the scientific conclusion, the information hasn’t been confirmed, and you go back to the drawing board and come up with a new hypothesis. That’s the scientific method.”

“Science is not value free,” Dr. Lackey said. “We decide what problems we work on or our boss tells us what problems we’ll work on, or we’ll get a grant or some research funding to do a certain thing, and that decision is in fact a value judgement, because there’s a zillion things we could do science on, but somehow we individually select or somebody selects for us the kinds of problems we’ll work on. Plus we could look at other ways to gather information, not just the scientific method, so science is not value-free but it is expected to be policy-neutral. That is, there’s no built in policy preference in science, science just deals with the ‘is’. This is the way the world is, it doesn’t deal with the way the world should be or ought to be.”

“Science is not value free,” Dr. Lackey said. “We decide what problems we work on or our boss tells us what problems we’ll work on, or we’ll get a grant or some research funding to do a certain thing, and that decision is in fact a value judgement, because there’s a zillion things we could do science on, but somehow we individually select or somebody selects for us the kinds of problems we’ll work on. Plus we could look at other ways to gather information, not just the scientific method, so science is not value-free but it is expected to be policy-neutral. That is, there’s no built in policy preference in science, science just deals with the ‘is’. This is the way the world is, it doesn’t deal with the way the world should be or ought to be.”

“Ideally, if it’s paid for by public money, it should be policy-relevant,” he said. “At least in my career, I didn’t do science just to advance knowledge; it was really designed to provide useful information to policymakers to help make decisions. So ideally its policy-relevant and not only that, it’s policy neutral.”

How important is science to water resource policy and management? Dr. Lackey said not as important as you might think. “It is particularly important in natural resource management or other fields,” he said. “It’s not unimportant, it’s not unuseful, and it is important – but it’s not at the core of most policy debates. Not only that, it’s only one type of information; there are plenty of other types of information; political scientists would make the argument that other inputs are more important than scientific inputs.”

PUBLIC TRUST IN SCIENTISTS

Scientists must be trusted if they are going to be helpful in policy making and management, because politicians, senior managers, or senior policymakers are not likely to be scientists in a particular field, so trust in scientists is crucial, he said. “The public doesn’t understand science, so if they are going to believe science, they have to trust whoever is presenting it. So the question is, what is the level of trust that people have in scientists, and by implication science? That’s a very hard question to answer.”

Scientists must be trusted if they are going to be helpful in policy making and management, because politicians, senior managers, or senior policymakers are not likely to be scientists in a particular field, so trust in scientists is crucial, he said. “The public doesn’t understand science, so if they are going to believe science, they have to trust whoever is presenting it. So the question is, what is the level of trust that people have in scientists, and by implication science? That’s a very hard question to answer.”

A national survey was done a few years ago, and one question asked average people, ‘How much do you trust scientists to present unbiased science about environmental issues?’ “Now this is not water resources, so it’s not exactly the question, but it’s as close as I could find of the degree the public has about trusting scientists,” he said. “How do you think the public would answer the question, how trusting they are of scientists when they talk about environmental issues? Well, the sobering conclusions to me were that four in ten Americans say they place little or no trust in what scientists have to say about the environment.”

You might think that the other six do, so 60% isn’t all that bad, but that’s not true, either he said. “The other 60% weren’t all that trusting,” he said. “Four in ten place little or no trust, and most of the other six were lukewarm. So who is out there in the public that distrusts scientists?”

You might think that the other six do, so 60% isn’t all that bad, but that’s not true, either he said. “The other 60% weren’t all that trusting,” he said. “Four in ten place little or no trust, and most of the other six were lukewarm. So who is out there in the public that distrusts scientists?”

Dr. Lackey said that there are only a few issues that have polling data and those issues are GMOs and particularly GMO agriculture; fluoridation of drinking water and the health effects of fluoridation; climate change, particularly the degree to which change in climate is caused by human factors; and the safety and risks of childhood vaccinations.

“If you look at these four case studies, where’s the skepticism of science going to be greatest?,” he said. “My guess is that you will probably say climate change and you would be wrong. The greatest skepticism of science is in the GMOs. And that skepticism comes primarily from the left side of the political spectrum.”

“The second greatest degree of skepticism of science comes from climate change, particularly the human role, and that skepticism comes from the political right,” he said. “Polling data in fluoridation showed that people didn’t trust the science, so fluoridation skepticism comes primarily from the left. If you look at the childhood vaccinations rates, the lowest vaccination rates are on the West Coast states, particularly California, and particularly Marin County, just above San Francisco. Those of you who know that area know that Marin County is not way a bastion of right wing zealots, so skepticism on childhood vaccinations again comes primarily from the political left.”

“So my conclusion is that you don’t want to overinterpret the data, but I think it’s safe to say that skepticism tends to come from across the political spectrum and it varies by issue, but it’s pretty much across the range,” he said.

“So my conclusion is that you don’t want to overinterpret the data, but I think it’s safe to say that skepticism tends to come from across the political spectrum and it varies by issue, but it’s pretty much across the range,” he said.

How in practice is science used and abused in water resource management policy? Dr. Lackey said that in the second phase of his career dealing with the interface of scientists and policy people, he identified two realities that help explain it.

REALITY #1: SCIENCE IS NOT THE KEY TO RESOLVING POLICY AND MANAGEMENT DEBATES

“The first policy reality is that science is not the key to resolving policy and management disputes. It’s important, perhaps even essential, and can be very useful, but it’s not at the key,” he said.

“The first policy reality is that science is not the key to resolving policy and management disputes. It’s important, perhaps even essential, and can be very useful, but it’s not at the key,” he said.

To illustrate his point on the role of science in public policy, he gave a case study of the Cape Wind Project, which was a large project off the coast of Nantucket, Massachusetts that was supported by the federal government, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and many others. It was to be a prototype for wind projects on both coasts.

“Now this was not your house on the prairie with a little windmill on the farm,” he said. “These are industrial scale projects; a human is dwarfed by the size of these structures. Also with wind power, the transmission lines are often more controversial than the actual project. Of course, like all energy projects, they have side effects that are not ideal; wind projects tend to kill a lot of birds and bats, and there are advocates who find that rather unappealing. So here’s the bottom line. After spending 12 years and many millions of dollars – a lot of it taxpayer money, the Cape Wind Project collapsed, and almost assuredly it’s not going to be built. So what we want to look at and figure out is, what role did science play and more specifically, what role did scientists play?”

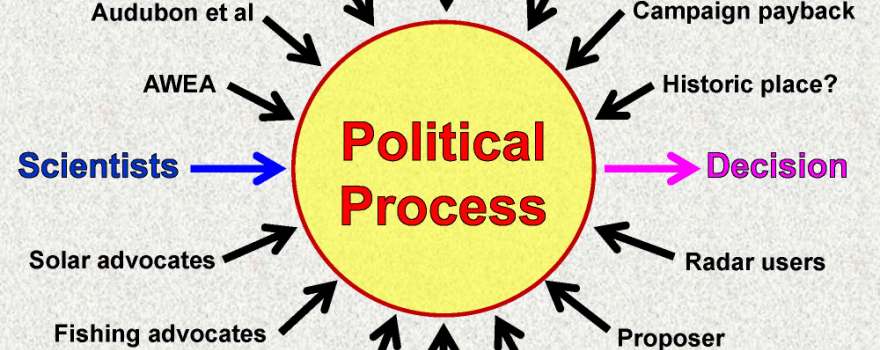

“With projects such as this, there are scientists who provide science into the political process, and out pops a decision, and that decision is informed by advocates of different types who support the project, and other advocates who tend to oppose it; so if there’s a problem with this, it’s basically because we lack science and if we had more science and better science and more relevant science, the decision would be reasonably obvious and we can move on with life,” he said. “But let’s look at this project a little more closely. Let’s deconstruct the case study in kind of a first level deconstruction.”

“With projects such as this, there are scientists who provide science into the political process, and out pops a decision, and that decision is informed by advocates of different types who support the project, and other advocates who tend to oppose it; so if there’s a problem with this, it’s basically because we lack science and if we had more science and better science and more relevant science, the decision would be reasonably obvious and we can move on with life,” he said. “But let’s look at this project a little more closely. Let’s deconstruct the case study in kind of a first level deconstruction.”

Dr. Lackey then ran down the different interest groups and stakeholders involved: There were climate advocates pushing the project, arguing that we need it to reduce our carbon footprint; there were other advocates who said it may be a great idea, just not here; and being Nantucket, the affluent individuals living there were opposed to have a windfarm off of their back deck. There were other interest groups, such as the Audubon Society, who were opposed because the project was on the Atlantic Flyway and would kill a lot of birds. The fishing advocates were opposed as the project was located in areas that had been fished for hundreds of years and their nets would be tangled in the underwater infrastructure, so they were opposed.

Then there were the industry advocates. The American Wind Energy Association, an industry group, was obviously supportive of the project. The solar advocates played in the arena a bit, but more subtly, he said. “Now these projects go because they either get tax credits or tax subsidies, and there is a limited supply of those, so a lot of those subsidies might also go to solar advocates, so solar advocates are kind of between a rock and a hard place,” he said. “They don’t to come out and be opposed to wind power, but by the same token, they want to work and land those tax credits as they can, so they are probably going to take the view of, well in general terms we’re supportive but you know solar is a lot more efficient, we can do this a lot easier, we don’t’ have such a big bird problem, etc.”

Graduate students studying this case have noted that NBC and MSNBC had a lot of ‘puff’ pieces – items that look like news but are really designed to push a particular agenda – on wind power; they also discovered that NBC was owned by General Electric at the time. “General Electric is the world’s second largest manufacturer of wind turbines, and so it’s not surprising that the media outlet that they owned might pitch wind power,” said Dr. Lackey, noting that NBC is not longer owned by General Electric.

Graduate students studying this case have noted that NBC and MSNBC had a lot of ‘puff’ pieces – items that look like news but are really designed to push a particular agenda – on wind power; they also discovered that NBC was owned by General Electric at the time. “General Electric is the world’s second largest manufacturer of wind turbines, and so it’s not surprising that the media outlet that they owned might pitch wind power,” said Dr. Lackey, noting that NBC is not longer owned by General Electric.

And then there are the taxpayers, he said. “Warren Buffett is on record multiple times saying, ‘I love wind power and I love solar power, too. I don’t care about those projects, but I care about those tax credits. They are worth a lot of money, so I invest in these projects because I want the tax credits.’ And of course, that is exactly what those tax credits were designed to do; pick winners and losers. If the government wants to create a market and activity for wind power and solar power and other kinds of things, is you basically put resources in there, picking winners and losers.”

“The counter argument is why is the government and the taxpayers picking winners and losers? Let the market decide,” he continued. “If people won’t put their personal money in these projects, that ought to tell you something. But of course, the counterargument to that is look, after the Civil War, the federal government wanted to take railroads and run them out to the West, but those are railroads to nowhere, nobody would put their private personal money in building railroads to nowhere, so the Governor essentially paid the railroad companies to put those tracks in. There is no right or wrong; those are different policy preferences.”

And then there are the health arguments, which are very hard for scientists and analysts to deal with. “Going back to the NIMBY not in my backyard, argument, no one ever makes the argument, I don’t want it in my backyard; they wrap their argument in something else, and the something else is often times a health issue,” he said. “A lot of people that have NIMBY concerns will say, it’s pretty clear that wind power creates or causes or brings out epilepsy in people, and so we have wind farm epilepsy which is alledgedly a health issue; or the constant sound of these turbines going around will drive people off the deep end. These are very difficult issues to determine if they are real or not, but they are very common in these debates.”

And then there are the health arguments, which are very hard for scientists and analysts to deal with. “Going back to the NIMBY not in my backyard, argument, no one ever makes the argument, I don’t want it in my backyard; they wrap their argument in something else, and the something else is often times a health issue,” he said. “A lot of people that have NIMBY concerns will say, it’s pretty clear that wind power creates or causes or brings out epilepsy in people, and so we have wind farm epilepsy which is alledgedly a health issue; or the constant sound of these turbines going around will drive people off the deep end. These are very difficult issues to determine if they are real or not, but they are very common in these debates.”

There is always the proposer of the project; it might be a local government or a state government. “In this case, it was the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, which was the main proposer; they wanted to do this project, and so you’ve got these people pushing the project.”

Then there are always the things that weren’t anticipated at all. “For example, the late Senator Kennedy opposed this project because it was off his front deck, his argument was, ‘The air force has a military installation nearby, and I’ve been told on good authority that this wind farm will cause problems with the radar system and put our military at risk, and I’m not going to support this project until it’s clear that this effect is not real.’ That took about three years to resolve and eventually it was resolved, but needless to say, it delayed the project for awhile.”

There were other issues that were almost unpredictable, such as two Indian tribes who argued that the areas now underwater where the project would be built were ancient burial grounds from hundreds of years ago when the water levels were much lower. “They petitioned the Department of the Interior to declare these areas where these windmills would be as historic protected areas so you can’t desecrate these areas because these are historic graves,” he said. “Now eventually the Department of the Interior said, ‘We’re not going with that,’ but again that caused some delays in the project.”

There were other issues that were almost unpredictable, such as two Indian tribes who argued that the areas now underwater where the project would be built were ancient burial grounds from hundreds of years ago when the water levels were much lower. “They petitioned the Department of the Interior to declare these areas where these windmills would be as historic protected areas so you can’t desecrate these areas because these are historic graves,” he said. “Now eventually the Department of the Interior said, ‘We’re not going with that,’ but again that caused some delays in the project.”

There are other issues that come into play that really have nothing to do with the project directly, such as political paybacks, such as ‘we supported your project several years ago, it’s time for you to support ours’, he said. “There is nothing wrong with this; this is how the world operates. But you need to understand it.”

“Every one of these types of cases has plenty of scientists for hire,” he said. “There are university people looking for research and science grants and contracts; there are consultants at large looking for work, and there are federal and state agencies looking to fund their research laboratories.”

So what’s the take home message? “First, yes you do have scientists out there, but science is used by nearly every actor in the policy debate. They are all going to have science involved,” he said. “Second, science is an effective advocacy weapon in public policy wars. If you survey people as an example, everybody will say they detest negative campaign advertising, but it will continue to be used because it works. And a lot of scientists will complain bitterly about how science is misused in these policy debates such as Cape Wind, but it will be continued to be used as an advocacy weapon because it works.”

So what’s the take home message? “First, yes you do have scientists out there, but science is used by nearly every actor in the policy debate. They are all going to have science involved,” he said. “Second, science is an effective advocacy weapon in public policy wars. If you survey people as an example, everybody will say they detest negative campaign advertising, but it will continue to be used because it works. And a lot of scientists will complain bitterly about how science is misused in these policy debates such as Cape Wind, but it will be continued to be used as an advocacy weapon because it works.”

“Third, think if you were involved in this project as a decision maker where you had to make an informed decision about how you might vote on it. As a user of science just trying to figure out what’s going on, whose science would you trust? Every one of these sources seems to have an angle including the government, which is in favor of this project, and so where do you get policy neutral science that you would actually trust?”

REALITY #2: NORMATIVE SCIENCE HAS A CORROSIVE EFFECT ON THE SCIENTIFIC ENTERPRISE

Dr. Lackey then turned to the second reality check about the use and misuse of science. “Normative science has a corrosive effect on the entire scientific enterprise, and I think the advent and the commonality these days of normative science has done a lot to undermine the trust that people and decision makers have in science.”

Dr. Lackey then turned to the second reality check about the use and misuse of science. “Normative science has a corrosive effect on the entire scientific enterprise, and I think the advent and the commonality these days of normative science has done a lot to undermine the trust that people and decision makers have in science.”

He defined the term ‘normative science’ as science with an embedded policy preference. “Normative science is science that looks like science, it sounds like science, and it’s usually presented by people that have the credentials of scientists – they look like scientists, and they act like scientists – but it has an embedded policy preference. Usually that assumed policy preference is rarely stated, so the average listener, the average reader of normative science is oftentimes doesn’t even pick up on the fact that they’re reading normative science, not regular science. Oftentimes the normative nature of the policy preference is embedded in how the science is presented.”

Dr. Lackey then clarified the difference between traditional science and normative science. Normative science is often described as advocacy science; it is designed to try to convince somebody that they ought to adopt a particular policy. “Philosophers like to talk about it as the slip between ‘is’ and ‘ought.’ Science deals with the ‘is’ – this is the way the world works; this is what’s likely going to happen given the current trajectory. ‘Oughts’ are policy statements – this is the way the world ought to be. We should make this decision. Perfectly legitimate, but they’re not science.”

Dr. Lackey then clarified the difference between traditional science and normative science. Normative science is often described as advocacy science; it is designed to try to convince somebody that they ought to adopt a particular policy. “Philosophers like to talk about it as the slip between ‘is’ and ‘ought.’ Science deals with the ‘is’ – this is the way the world works; this is what’s likely going to happen given the current trajectory. ‘Oughts’ are policy statements – this is the way the world ought to be. We should make this decision. Perfectly legitimate, but they’re not science.”

How does traditional science become normative science? Dr. Lackey presented a second case study using the California drought. Drought is not uncommon for California; considering the climate history for the last 1200 years, the last 150 years have generally speaking been pretty wet. Even so, there have been droughts, such as the 1928-32 drought; going back even further, there is evidence that drought last ten to twenty years and were much more severe. There have even been megadroughts lasting a century or more and must more serious. However, nowadays, even the routine droughts cause problems.

A couple of years ago, California passed Proposition 1, which provided funding for water projects. “One of the things it had in it was to look at the feasibility of creating more dams to store more snow runoff,” Dr. Lackey said. “This isn’t an original idea; there are plenty of dams built to do that exact function, but there’s still additional possibility to store more runoff. So the issue on the table is put a dam on river A to create reservoir B.”

“Let’s play a participatory game,” he continued. “Imagine that you are a member on the Governor’s multi-disciplinary study to assess the ecological or environmental or whatever effects on a proposed dam. After 3 years, you finish your report, and we’ll stipulate that this report is fabulous. There is no scientific debate. There’s never been a report like this, but just imagine this was the perfect report. How would you present your results to the public, to the Governor, or to anybody else? What kind of words would you use to describe this science which is beyond debate?”

“Let’s play a participatory game,” he continued. “Imagine that you are a member on the Governor’s multi-disciplinary study to assess the ecological or environmental or whatever effects on a proposed dam. After 3 years, you finish your report, and we’ll stipulate that this report is fabulous. There is no scientific debate. There’s never been a report like this, but just imagine this was the perfect report. How would you present your results to the public, to the Governor, or to anybody else? What kind of words would you use to describe this science which is beyond debate?”

“Would you use words like ecosystem degradation? If the term ‘ecosystem degradation’ is used in scientific reports, in my view, that’s normative science, because what that implies is condition A free flowing river is superior to condition B, a dammed river. There’s no doubt that there are very different ecosystems, there’s many changes there, but they are not better or worse until you apply a policy preference, and that is outside the realm of science. You could take the exact same science, no difference, and call it ecosystem improvement. Is that normative science? I would say clearly yes, because if you’d say that, you’ve said in effect condition B is better than condition A, therefore you’ve improved it. There’s nothing in the science that says that condition B is better or worse than condition A until you step outside of science and apply a policy preference.”

“The better terminology to use is words like ecosystem alteration,” he said. “There is no doubt that ecological function and environmental function, hydrology, everything else – the whole bit, is greatly different between these two states, but they are not better or worse until you apply a policy preference.”

“The better terminology to use is words like ecosystem alteration,” he said. “There is no doubt that ecological function and environmental function, hydrology, everything else – the whole bit, is greatly different between these two states, but they are not better or worse until you apply a policy preference.”

How as a scientist do you determine if you have slipped into normative science? Dr. Lackey recommends that you ask others what policy message is conveyed, what did they hear when they either listened to you or read. Most of us live in disciplinary tribes; the people we work with tend to share the same political views, so you have to step outside that and ask somebody on the street. “It’s not about your intent. What you intend to do is provide policy neutral science, but the question is what does the person hear? What knowledge is actually conveyed?”

CONCLUSIONS

“So those were the two realities about science and water resource management,” he said. “First of all, science is not the key to resolving policy and management disputes; it’s important yes, but not the key. And normative science has a corrosive effect on the scientific enterprise.”

Dr. Lackey then offered seven take home messages:

- Policy making is about picking winners and losers. “That’s just a fact of life, and therefore since management implements policies, you should expect management to be similarly contentious. There are always winners and losers, and my experience is the losers are never entirely happy about being political losers.”

- It is clashing policy preferences or values and not science that are typically at the core of policy debates. “People have different values, and science really can’t do anything about that. Those values are there, they are not based on science, they are based on other kinds of things, and so science really can’t contribute to resolving that.”

- In a democracy, the values, that is the policy preferences of scientists are no more important than the values of others. “It’s always important to recognize that we do live in a democracy versus a technocracy. Scientists are experts in their scientific field of knowledge, but when you step outside of that and get into value debates, which is really at the core of policy, the values of scientists are no more important or valuable in a democracy than the values of anyone else.”

- Policy advocates will routinely wrap themselves and their pitches in science, and this okay. “The job of an advocate is to solve the policy preferences of himself or the organization, and they’ll use whatever technique works. So they’ll use and misuse science, and that’s perfectly ok. It’s not good science practice, but they are advocates trying to pitch their policy preference, and they wrap their preference in science as this will tend to sell better with the public, and this is perfectly fine.”

- Policy advocates, both individual and groups, will oftentimes hide policy preferences in what appears to be policy-neutral science. “It’s normative science, and a good advocate can make science that’s advocacy science look just like regular science, and if you’re effective in your advocacy, the average reader will never pick up on it.”

- For a scientist, whether it’s intentional or not, using normative science is stealth policy advocacy. “The reason it’s stealth is because the average reader doesn’t even realize that you’re subtly pitching a policy preference. And so you can’t hide behind the view that it was an innocent mistake. Whether it was innocent or not, you are in fact slipping into policy advocacy.”

- Sticking to policy neutral science or traditional science does not preclude playing a useful role in policy, management, or efficacy. “I’m not of the view is to stay in your laboratory and periodically publish peer-reviewed literature, and maybe somebody out there might find your article and might find it useful. I think that especially if you are a publicly funded scientist, you ought to play in policy management advocacy, but play the role of the scientist and don’t get coopted into becoming a policy advocate.”

Dr. Lackey concluded his presentation with a suggestion for early career scientists. “These can be very divisive policy issues, and you want to develop your understanding of science before you get dropped into a crisis like this. The role of policy neutral science can be very clear, but you have to have your act together before you get beat on in types of arenas.”

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

Question: Given the recognition that all framing of projects and generation of hypotheses is shaped by values, where do you draw the line between recognizing how scientist’s implicit values influence their work versus normative science?

“Well, that’s a difficult question and a very perceptive question,” Dr. Lackey said. “For example, I have no problem if your employer or grant or some other way defines their policy problem hence the research question – that is a value judgment. Now the question I always say is when you do that study, you answer the question, ‘given the question was this, which was given to me, here is the best science on the question’ and avoids the extent as possible any implication of any policy preference. There’s not a clear cut, clean answer. The key thing is to be well aware that it is very easy to have your science slip into the fact that it tends to favor a particular policy option.”

Question: We know that the climate is constantly changing due to many factors. The current administration often states that climate change is predominantly man-made and settled science. Would you consider that normative science?

“That’s a loaded question,” answered Dr. Lackey. “The issue about the extent to which humans have been involved in climate change is of course a legitimate question because the views range all the way from 100% to 0. Now my guess is, and this is purely a guess, when I talk to scientists who do this kind of work around here and elsewhere, there’s probably a human contribution and there’s obviously a natural contribution; I’m sure there’s both. The question is really where on that continuum does that lie? I think that’s open to debate. Now I think anybody who works on that problem says it’s open for debate; now let’s assume it was 50/50, 50% of climate change is due to human actions, 50% is natural. Policy people could say, hey 50%, we better get cracking and do something about that. Well, you could look at the same science and say, it’s only 50%, it’s a waste of money, let’s not do this, it’s going to cause a lot of social dislocation, let’s forget it. So even if you agree on the science, there are lots of different policy options that people can legitimately argue for.”

Question: Do you think the issue of the mistrust of scientists has increased since the beginnings of the climate change debate? Has that exacerbated public mistrust?

“My guess is as I look back at my career when I started as a graduate student, at the time it seemed the public was more trusting of scientists,” Dr. Lackey said. “That’s not based on data; that’s just anecdotal. And I think what has happened is that so many of the policy debates, whether they are GMO or climate change, fluoridation of drinking water, or any of these other ones, in the public’s mind they seem to pivot on science, so therefore science becomes a surrogate argument for value debates. So we argue vociferously over scientific issues on GMOs and climate change and childhood vaccinations, but at the end of the day, the debates are really over values – who wins and who loses, what’s important to society, so the science is really become almost a lightning rod for value clashes.”

Question: What about academic faculty or research science positions that are funded by an advocacy group?

“That’s a real issue,” replied Dr. Lackey. “Let’s just think about this. I’m sitting here on the campus of Oregon State University, and let’s just say hypothetically that there were two groups that wanted to endow a chair at Oregon State and you tell me how would you react to these two groups. The first group comes in and says, we want to endow a chair to study conservation biology, and it is the American Petroleum Institute. The very next week, a second group comes in and says we want to fund an academic chair to study conservation biology, and that is this Sierra Club. Now as a university, would you take both? As a faculty member, would you be happy with the Sierra Club funding an endowed chair and not the American Petroleum Institute? Or would you be happy with the American Petroleum Institute and not the Sierra Club, or would you take neither or both? I don’t have a great answer to the question, but I have strong reservations about the issue and the perceived independence of endowed chairs that are funded by what would normally be perceived as advocacy groups.”

Question: What are techniques for bringing the policy embedded in normative science out into the open? Also, can a decision on what to apply science to, in other words, what to study, also be influenced by policy?

“Taken in reverse order, the last part of the question is that when decisions are made about what to fund, that is entirely a policy determination, and I use this specific example of my own experience. I worked for EPA on a research arm for a long time; this is the research arm that is independent of the main office and the regional office; it’s supposed to be independent of the regulatory part of EPA. When we dealt with the policy people, particularly policy analysts which really formulate options for policy makers, they had an interesting way they worked on problems. I learned a lot from them; they are really bright people. They would do sensitivity analysis. They would come in and they would look at those scientific questions and assuming we could answer them, say which ones would make a difference in the policy decisions on the table. About 95% of the things that we could do research on, they would essentially say, ‘That would be nice science, it would be interesting science, and would probably move the ball down the field in terms of scientific understanding, but it’s not going to make any difference in policy.’ It’s the 5%, the high sensitivity information issues that we need answers to, and invariably, those were the most difficult ones to answer scientifically. So very much determining what to ask is a decision. The counter aspect is that there are only a certain number of things that science can actually do, and so as an interface between science and policy, look for the overlap. What can we do as scientists, and what do you really need to answer your particular policy question.”

Question: In terms of fish passage, a dam definitely degrades the corridor. It’s using degrade in that instance normative science?

“First of all, I would question when you use the terms like degrade, why do you use them?,” Dr. Lackey answered. “Why not say, if you put a dam in, you’re going to very much reduce the run, perhaps eliminate the run; if you put fish passage in, it’s never as good, here’s how it’s never as good as not having runs. That doesn’t mean society shouldn’t do it; it means you ought to be aware of the effects and you ought to describe the effects. When you get into terms like ‘degrade,’ ‘better,’ or ‘improve,’ to me those tend to convey value judgments. If I listened to that question the way it was phrased, I would say the scientist is not really enthused about having a dam there, and a scientist ought to be neutral on that. There is no question. You put a dam in; it will adversely affect fish runs. Now if society wants to bear that cost or not, that’s a question for society to make, not for scientists.”

Moderator Michael Campana asks, if you were testifying before a congressional committee or something, and they said, Dr. Lackey, if we put dam A in there, is it true that species A which likes a free flowing river will become extirpated or something like that. For you to answer that honestly and say yes, there’s a strong likelihood, are you being normative or … ?

“That’s a statement of scientific fact but it’s true. If you put a dam in here, it’s likely to reduce the run 80% and the confidence interval is 50-90% down – those are statements of scientific fact,” replied Dr. Lackey. “The counter argument is if you are downstream and you are getting flooded out every year, you say, I don’t really care about the salmon run, I want my floods solved. Those are societal decisions; they are not on scientists, so I have no problem being incredibly blunt with congressional members … “

Question: Have you ever had your scientific results misrepresented, and if so, how did you handle it and what were your recommendations?

“Very good question, and unfortunately hits close to home,” said Dr. Lackey. “A long time I was involved in place here on this exact issue with the salmon runs, and I was being pestered by a newspaper reporter; it happened to be Snake River dams, and the newspaper reporter kept saying over and over that the debate on the table here is should these dams come out? And I said, that’s not a science question, that’s a personal policy preference. He kept saying, you’re the scientific expert, tell us what we think. Finally he said, ok, I understand what you’re trying to accomplish here. What if in fact I said to you, this is what the reporter said, if we want to bring up salmon runs to Idaho, should these dams come out? And my answer was what I think is a scientific fact: yes if you want to bring back significant runs of wild salmon to Idaho, these dams need to come out, that’s a scientific fact. The next morning, what do I get is a call of the EPA administrator saying, looking at the headlines, says ‘EPA scientists say, dams ought to come out.’ You go through ‘Well that’s not what I said’ … ”

Question: From a scientist point of view, do you have any opinions on how decision makers should consider input received from community members or stakeholders about their values in conjunction with information provided by scientists? Sometimes the science will better support one decision while the people’s values are more supportive of a different decision.

“That gets involved in basically in a decision making process and democracy; it’s a trade-off between winners and losers and so forth,” said Dr. Lackey. “Science tends to say which policy options will not work as expected or hoped for, but among the options that are on the table and will still ‘work’, there are many. And so I don’t think scientists can help in terms of among the remaining options, which ones are preferable. The science is just what it is. The tradeoff values, that’s the core of democracy, that’s not science issue; that’s a democracy issue.”

Question: There might be issues with funding research from advocacy groups, but what about government funded research. Can’t it also be contentious?

“Let’s not be naive here,” said Dr. Lackey. “If you are in administration and you have certain policy perspectives, you’re going to fund the science that you think can be packaged to sell your policy preference. If you have policy preferences and you want to make a case that supports your policy preference – if you’re a government agency or a government administration, federal administration or state, you can fund the types of research that will tend to support the kind of policy preference you have. I think that is one of the reasons the public has become so skeptical because the public’s not stupid; they recognize that.”

Question: What information would a scientist put in a disclosure text block regarding funding or policy underlying this study?

“When I worked with EPA, the standard disclaimer was twofold: one, it was funded be EPA, statement of fact, and then, ‘nothing in this scientific article should be construed to be endorsing or not endorsing a particular policy,’ so in essence say, this is purely a scientific document, doesn’t convey any policy preference. I think to the extent you have to be honest with people, is there anything that if the leader of your paper knew all of the relevant facts, he might or she might question your independence, I think you have to be honest with people and say, is there anything in here that would call into question my impartiality, calling it the way it is. I don’t have a clean algorithm to put that information in there, but I would always err on the side of more information rather than less.”

Question: For clarification, where does the role of economics and benefit cost analyses fit within your statements about normative analysis and proposed actions?

Question: For clarification, where does the role of economics and benefit cost analyses fit within your statements about normative analysis and proposed actions?

“Benefit cost analysis is basically a tool that policy analysts use on the question of distribution of benefits and costs,” Dr. Lackey said. “You can do a benefit cost analysis, but that doesn’t necessarily mean a particular decision could be made. Ultimately, at the end of the day, decisions are political, ie picking winners and losers. Benefit cost analysis might help you make a decision, but ultimately it’s not going to drive a decision, unless there’s particular legislation that says it must, so benefit cost analysis can be useful, but it’s just like science. It doesn’t presuppose there is a best decision. Just because something has a high benefit cost ratio, doesn’t necessarily mean society wants to do it.”

Click here for the webinar video.

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!