This month’s update covers the proposed revised schedule for development of the regulation, climate change analysis, the peer review process, and an overview of the technical reference document

This month’s update covers the proposed revised schedule for development of the regulation, climate change analysis, the peer review process, and an overview of the technical reference document

In November 2014, California voters approved Proposition 1, a $7.5 billion water bond for investments in the state’s water systems; of that, $2.7 billion was allocated for the public benefits of surface and groundwater storage projects. The California Water Commission is the agency responsible for allocating these funds, and will select water storage projects for funding based on their public benefits through its Water Storage Investment Program.

At the July meeting of the California Water Commission, staff updated the commissioners on the latest schedule revisions, the proposal for how to incorporate climate change into applicant’s analysis, a discussion on the peer review process, and an overview of the technical reference document.

Here’s what they had to say.

SCHEDULE

The statutory deadline for the California Water Commission to adopt the regulation for the Water Storage Investment Program is December 15, 2016. The Commission released the first draft of the regulation and entered the formal rulemaking process on January 29th; the public comment period closed on March 14th, and since then, a subsequent draft of regulations has not been released. With time running out, Dave Gutierrez, having just finished the groundwater sustainability plan regulations, has been brought in to finish the process.

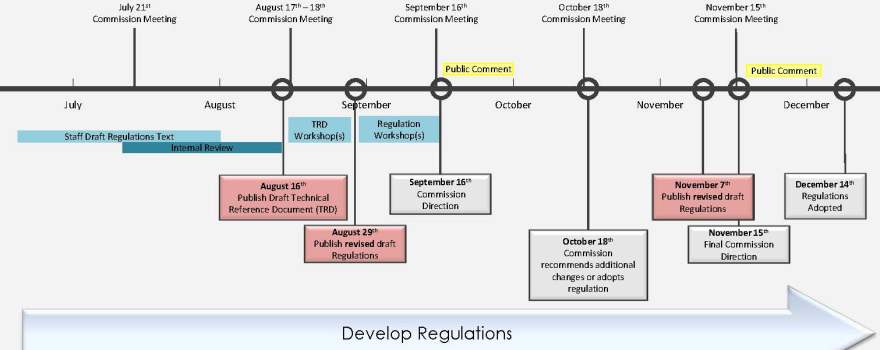

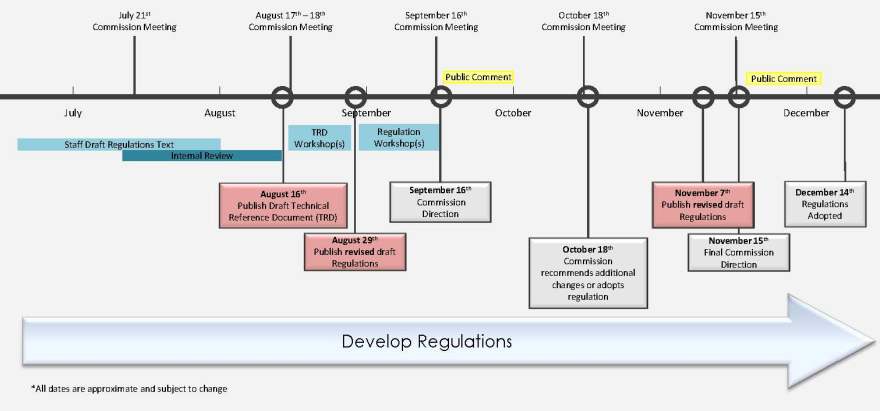

At the July meeting, Acting Executive Officer Rachel Ballanti presented an updated schedule for completing the regulation within their statutory deadline.

At the July and August meetings, Commission staff will be presenting the concepts for the regulations. The August meeting is scheduled for August 17 and 18. This month, staff will be reviewing climate change and peer review process; in August, all of the outstanding concepts in the regulation, including the evaluation criteria, will be presented. Although these are not official actions, staff is looking for clear direction from the Commission. This is needed to write the regulation language, but doesn’t mean the decision is necessarily final, reminded Ms. Ballanti.

At one time, there was discussion that there would be two regulations, one for the quantification of public benefits, and a second for the Commission’s evaluation criteria; however, now both the quantification of public benefits and the evaluation criteria will be included in one regulation.

The schedule is tight, and each component is part of the critical path, Ms.Ballanti said. As many opportunities for deliberation and discussion as possible have been built into the schedule.

Draft technical reference documents will be released in August. The technical reference documents will give guidance on the quantification of public benefits for applicants. It will be released in mid-August to allow plenty of time for public and Commission review. Workshops will be held around the state during the last two weeks in August to present the document and allow members of public to ask questions and interact with staff.

The plan is to release the draft text of the regulation on August 29th. Following the release of text, there will be one public workshop in early September.

At the September meeting, scheduled for September 16th, the regulation text would have been available for two weeks; the Commission would be asked for direction to move forward with a formal 15 day public comment period in the OAL regulation process. Although 15 days is the requirement for public comment, they plan to release the regulation text and technical reference document well in advance of the public comment period.

Following the public comment period, the staff and the Commission will review the comments, theoretically if no additional changes, Commission could adopt the regulation as early as October. However, Ms.Ballanti acknowledged that in all likelihood, additional changes will need to be made based on those comments. The Commission will need to use the October and November meetings to direct those changes. At the November meeting, the Commission will need to give final direction on significant issues on what is to be included. There would be one more formal 15-day comment period.

At December meeting, scheduled for December 14th, the Commission would be asked to adopt the final regulation, and if the Commission adopts the final regulation at that meeting, it would be prior to the statutory deadline of the 15th. After Commission adoption, the regulation package will be sent to OAL who will have 30 working days to review it.

Commission staff anticipates holding additional public workshops or meetings in October and November, as well as additional tribal consultations.

CLIMATE CHANGE ANALYSIS OVERVIEW

Over the next several weeks, David Gutierrez and his team will be finalizing the next draft of the regulations. “Our objective in finalizing those regulations is to complete a version of the draft regulation as in close alignment as possible with the majority of Commission member’s direction,” he said. “In terms of the schedule, I think it’s important that we try to limit the number of versions we’re going to be presenting to you over the next six months, and therefore that’s why it’s kind of important to understand and get this regulation into alignment with your direction.”

During the next two Commission meetings, staff will be giving presentations on key components of the regulations; they will try to clarify some points, promote discussion on these issues, and then get final direction from Commission members. “I think we all have to realize that in some cases, we’re certainly not going to seek consensus from the stakeholders, and in reality we’re not even going to necessarily seek consensus within Commission members, but it’s important for us as staff to have an understanding of where the majority of the Commission wants to go on a particular issue,” he said.

Mr. Gutierrez said that at today’s meeting, they would be talking about climate change and peer review. “We’ll be presenting the approach that’s been developed by staff, which is the most efficient approach that staff felt and it was also consistent with what staff had understood the Commission direction on these issues are,” he said. “We’ll be presenting the recommendations and we’ll be discussing the approaches, and then what we’re looking for is we’d like to do is after points of clarification on the technical issues, we’d like to pause, allow for some stakeholder input, and then I’d like to come back at the end and talk to the Commission to finalize the direction on these particular two issues and whether or not you agree on the direction that we’re going on these.”

“Andrew Schwartz is going to be giving a presentation and he is going to lay out the approach; he’s going to be talking about how we’re going to be implementing climate change in consideration for understanding public benefits and resiliency of the projects,” he said. “The approach is developed consistent with Commission commitment to implement the executive order to factor climate change into the investment decisions and we’ve tried to develop a project to do just that. That’s difficult because what we’re trying to do is balance between being technically sound, sophisticated enough, yet we need to appreciate the infancy of climate science.”

“I think we need to have a good understanding of what this approach really is going to do, and just as importantly, what this approach is not. Specifically we need to understand this is a gross approximation of the effects of climate change on projects to allow the Commission members to understand a general direction or a trajectory of how climate may affect projects in the future.”

However, Mr. Gutierrez said it’s important to understand that this analysis doesn’t necessarily represent what is going to happen. “We are not intending this to be used to evaluate the viability of any one project, but instead what we’re trying to do is we’re trying to make a comparative analysis, and that’s where this type of analysis with these types of uncertainties is appropriate.”

It’s not just uncertainties associated with climate change; it’s also the uncertainties associated with the analysis, such as the uncertainties that are associated with the data, hydrologic modeling, future project conditions, future water and land use, regulations that may or may not change in the future, and there may be future water projects that have an effect on the overall system, he said. “We have to keep all that in mind as we move forward and understand what we’re trying to achieve with the analysis that we’re going to be doing.”

Mr. Gutierrez acknowledged that California is the leader in implementing climate change policies. “This would be unprecedented in the way that we’re actually presenting it today, it hasn’t really been used before for consideration of grant applications, but California is the leader and we are committed to consider climate change when we invest public dollars into projects of the future, and so therefore it is important.”

“What we’re trying to achieve is a comparative analysis,” he said. “We’re not necessarily trying to judge the viability of a project, so from a comparative analysis, we believe the method that we’ve developed should work.”

Mr. Gutierrez then turned the floor over to Andrew Schwarz to discuss the climate change analyses.

PROPOSED REVISIONS TO CLIMATE CHANGE ANALYSES IN WATER STORAGE INVESTMENT PROGRAM REGULATIONS

“We talk about uncertainty, and oftentimes people think it means that we don’t know anything about the future, but that’s not what it really means,” began Andrew Schwarz. “We have different kinds of uncertainty. One type of uncertainty is that there are things we know will change in the future, and we know we have some idea of how they are going to change.”

Any planning project has to deal with uncertainty about future conditions; for things like population and land use, we have some idea of the trajectory and the magnitude of change, and so we incorporate that in our planning, he said.

“Then there are these things about the future that we know are going to change but we really have no idea how they are going to change,” he continued. “Nobody believes that Delta regulations and environmental regulations to protect fish in our rivers are going to be the same in 50 years. They haven’t been the same for the last 10 years, so why would we believe that in 50 years, they are going to be the same way they are today? But we really have no idea what is the better assumption than the status quo. We don’t have a better assumption because we really don’t know how those things are going to change and in what way.”

“Then there are these things about the future that we know are going to change but we really have no idea how they are going to change,” he continued. “Nobody believes that Delta regulations and environmental regulations to protect fish in our rivers are going to be the same in 50 years. They haven’t been the same for the last 10 years, so why would we believe that in 50 years, they are going to be the same way they are today? But we really have no idea what is the better assumption than the status quo. We don’t have a better assumption because we really don’t know how those things are going to change and in what way.”

We don’t know what infrastructure is going to be built in the future, and if we make assumptions about certain infrastructure being built, that can highly bias our decisions if that infrastructure ends up not getting built; technology improvements, agricultural water efficiency – we just don’t know, he said.

There are other kinds of error that we know exist and we’re getting better at reducing, such as systematic errors in the models, climate modeling downscaling, and hydrologic modeling, Mr. Schwarz said. “These are models; they are not perfect, and there are some errors in them, we understand that error and we’re working to reduce it, but it’s there and we have to acknowledge it.”

This can be thought of as a cone of uncertainty where we’re at the tip of that cone and we feel like we understand what the conditions are right now, but as we move out into the future, that space where we can end up gets wider and wider as there are lots of different pathways that we can take to get to any one point at the end of that cone. We don’t have a way to predict how we’re going to move through that cone of uncertainty or where we’re going to end up, he said. “Where we’re planning for is kind of at the center of that cone, where the most likely future that we think is going to happen based on all the possible outcomes, but that doesn’t negate the possibility that we end up on the edge of that cone somewhere in some kind of less likely possibility.”

He presented global climate model (GCM) output data for temperature, noting that out into the future, the line is getting higher. “Every year there’s lots of interannual variability in there, but it’s getting higher in general and we can see a trend line clearly,” he said. “How we use this information and these proposed regulations and for water planning is a little bit more complicated than just taking the temperature and precipitation signal that comes directly out of a GCM, plugging it into a hydrologic modeling, getting some runoff, running that through our operations model and telling you all how much water is going to be available in the system at 2030 or 2070.”

He presented global climate model (GCM) output data for temperature, noting that out into the future, the line is getting higher. “Every year there’s lots of interannual variability in there, but it’s getting higher in general and we can see a trend line clearly,” he said. “How we use this information and these proposed regulations and for water planning is a little bit more complicated than just taking the temperature and precipitation signal that comes directly out of a GCM, plugging it into a hydrologic modeling, getting some runoff, running that through our operations model and telling you all how much water is going to be available in the system at 2030 or 2070.”

“All of these GCMs start in about 1950 and run through 2100, so we have a 65-year period of reference that we actually lived; we don’t have uncertainty about GHG concentrations in the atmosphere from 1960 to 2016 – we know exactly what they are, and we can run the models with those. We know what land use was, we know what these various feedbacks were, and so we can see how that model performed over a period of reference that we actually lived and see how good those models are.”

What we have found is that the global climate models do a very poor job of picking up the interannual variability in California’s hydrology and the way that the precipitation falls. “The GCMs just don’t seem to be able to pick up that hydrologic variability, and so we don’t necessarily trust the signal exactly from these GCMs for California,” he said. “That’s really not what the GCMs were ever designed to do anyway. They were really designed to understand general trends about climate in the future, and so that’s what we want to take out from these GCMs.”

“So what we do is we can see how much we take for a reference historical period, then we have a future period, let’s say 2015-2045, and we can see the difference between that reference period, that it got about 1 degree warmer between those two periods on average,” Mr. Schwarz said. “Then we can take that through some complicated math and statistical formulations, and map that onto our historical record of precipitation, and that’s basically what we do. We’re using the best data source that we know we have which is our observational dataset … we know it’s going to be warmer in the future, so we’re mapping that warming signal onto the historical record and we’re using that to create these climate change signals.”

Staff is proposing to present a near-term future from 2016 to 2045 and centered on 2030; and a late-term future from 2056 to 2085 and centered on 2070.

Mr. Schwarz then presented a graph of temperature showing four lines. “The gray line is what we actually lived, that’s our temperature signal for whatever grid point this is for somewhere in the state, and you can see there was a warming trend since 1922 to 2003; that’s the historical record that we typically use,” he said. “The black line is where we’ve tried to detrend that; we tried to add the warming that we experienced at the end of the century to the beginning of the century period as well, so we have a flat historical sequence that doesn’t have a trend in it. It’s flat. This is interannual variability and temperature that could occur today, that is what the black line is. In any year, we see those kinds of interannual variability at this point in time. The yellow line is the warming we expect to occur between now and 2030, the mid early century period. Then the red line is the late future period of 2070, that’s the amount of warming that we would expect to see, and that’s pretty significant.”

Mr. Schwarz then presented a graph of temperature showing four lines. “The gray line is what we actually lived, that’s our temperature signal for whatever grid point this is for somewhere in the state, and you can see there was a warming trend since 1922 to 2003; that’s the historical record that we typically use,” he said. “The black line is where we’ve tried to detrend that; we tried to add the warming that we experienced at the end of the century to the beginning of the century period as well, so we have a flat historical sequence that doesn’t have a trend in it. It’s flat. This is interannual variability and temperature that could occur today, that is what the black line is. In any year, we see those kinds of interannual variability at this point in time. The yellow line is the warming we expect to occur between now and 2030, the mid early century period. Then the red line is the late future period of 2070, that’s the amount of warming that we would expect to see, and that’s pretty significant.”

Staff are trying to make this as streamlined and simple for applicants as they can, so they will be providing tools and data to help with the analysis. “We realize that we’re asking for a lot of analysis here,” he said. “We want them to evaluate both 2030 and 2070 conditions for their without project or for their with project conditions, so we want to give them as many tools as we can and that we’ve done as much work as we can. It will also make sure that all of these projects are consistent as they will be starting with the same set of data.”

Mr. Schwarz said the Department will be providing for both the near-future (2030) and late-future (2070) scenarios:

- An 82-year gridded monthly Temperature and Precipitation across the entire state

- 82-year gridded monthly hydrologic runoff terms

- 82-year monthly streamflows for Central Valley rivers

- 82-year monthly CalSim-II model code and results for baseline and without project conditions

- DSM2 model codes and results – used for sea level rise

He explained that monthly hydrologic runoff terms is a technical term for what comes out of a hydrologic model. “You actually need streamflow routing to change that to streamflow, something that you can use, but we don’t have the streamflow routing for everywhere in the state, so what we can give them is the runoff terms. Then for their general watershed, they will probably have hydrologic modeling and the streamflow routing that they can covert that to runoff. We don’t have to tools to do that across the entire state. We do have the tools to do that for the Central Valley rivers, so we will give them streamflows for the Central Valley rivers.”

“We’re doing this because we want consistency across all of these analyses, we want all the applicants using the same tools and data, and we want it to be easy to use for them so they can do it quickly,” he said. “We’re giving them 6 months to do this analysis, which we think is adequate given the amount of tools and data we’re going to be providing them. We want it to be easily comparable for staff at the end of the day, so we can make an apples to apples comparison between these projects – which project does better across this assumption of future climate.”

Applicants will be given two data points, without project conditions at 2030 and 2070. “Those two blue dots, that’s any benefit. The benefits that are being provided by the existing system today, we think those will probably go down in the future as climate change takes hold and it gets warmer, so we’ll be able to provide less and less benefit with the existing system,” he said.

Applicants will be given two data points, without project conditions at 2030 and 2070. “Those two blue dots, that’s any benefit. The benefits that are being provided by the existing system today, we think those will probably go down in the future as climate change takes hold and it gets warmer, so we’ll be able to provide less and less benefit with the existing system,” he said.

They will already have existing conditions for their project from the CEQA analysis, so they will have a without-project and probably a with-project analysis of their project at the existing conditions, and they can calculate the difference in benefits between those, he said.

“What they’ll do is they will calculate these two other red dots using the data and models that we’ll be giving them; they will add their projects to the data and the CalSim code that we’ve given them, and they’ll be able to then model what the project is able to produce in terms of benefits at these two future time periods. Then they will start to compare between these two dots, so existing conditions with and without the projects, near future with and without the project.”

Mr. Schwarz pointed out that it is just the arrows between the two dots that they are calculating. “They are not trying to calculate a difference from existing conditions without the project; they are only comparing to a future with climate change with or without the project,” he said. “We don’t’ get to choose the future, the future is going to choose us; we get to choose whether we build the project or not. That’s the choice that we’re making.”

“They’ll make these three different comparison, they’ll get three different deltas, with those three values, they can then interpolate between the values as a straight line, a linear interpolation of what the benefits in every single year of the planning horizon would be for the project,” he said. “They have a Delta benefits, change in benefits, the actual benefits of the project, the net benefits of the project. In this example, the project starts in 2026, so you would have some value at 2026, some value at 2027, some value at 2028, and so on. And then they would calculate the net present value of that.”

“The important thing is that you’re summing all of these benefits across all these years, but you’re discounting future benefits,” he said. “The future is less certain, so we value benefits in the future less than we value benefits today. … Benefits that accrue much later out into the future get discounted more and more. The discount number in the right hand column, it’s going to get bigger and bigger so you’re discounting those numbers, and so the fact that these benefits are less certain is kind of mitigated to some extent by the fact that they are also less valuable.”

Mr. Schwarz acknowledged that the analysis they are asking applicants to do represent the most likely future conditions, but there is huge uncertainty in climate projections. He presented a graphic showing 20 different global climate models, noting that the different colors represent different assumptions about what different GHG concentrations in the atmosphere will be over the next 100 years.

Mr. Schwarz acknowledged that the analysis they are asking applicants to do represent the most likely future conditions, but there is huge uncertainty in climate projections. He presented a graphic showing 20 different global climate models, noting that the different colors represent different assumptions about what different GHG concentrations in the atmosphere will be over the next 100 years.

“You can see these things fan out to a great extent and this is just temperature … we don’t know where we’re going to end up,” he said.

Another way to look at it is with a probability space. “The blue mid-century climate probability space is about 2030 or 2040,” he said. “If you plot average change in temperature versus average change in precipitation for these GCMs, and you get this kind of probability space. There are still these models that project that we’re going to be way out here on the edges where it’s going to be hotter and drier or actually pretty cool and wetter, and maybe we’d have nothing to worry about. Here’s the range that we’re seeing just a mid-century, it’s huge. There’s a 40% swing in the possibility of what we think the change in precipitation might be, from -18 to +26.”

Another way to look at it is with a probability space. “The blue mid-century climate probability space is about 2030 or 2040,” he said. “If you plot average change in temperature versus average change in precipitation for these GCMs, and you get this kind of probability space. There are still these models that project that we’re going to be way out here on the edges where it’s going to be hotter and drier or actually pretty cool and wetter, and maybe we’d have nothing to worry about. Here’s the range that we’re seeing just a mid-century, it’s huge. There’s a 40% swing in the possibility of what we think the change in precipitation might be, from -18 to +26.”

To address the uncertainty, they also want to ask applicants to do a sensitivity analysis. “In the regulations, this would be fairly general and permissive in how they want to do it; it can be quantitative, it can be qualitative – they can do it in a number of ways,” he said. “The sensitivity analysis would explore these two extreme ends of where the projections suggest the future might be, so we would develop two more scenarios of future climate at the 2070 time horizon that explore an extreme warming, extreme drying condition and a very minimal warming, extreme wetting condition. Under less warming, wetting conditions, there are certain projects that would probably provide a lot of benefits under a scenario like that, so we want to explore that.”

To address the uncertainty, they also want to ask applicants to do a sensitivity analysis. “In the regulations, this would be fairly general and permissive in how they want to do it; it can be quantitative, it can be qualitative – they can do it in a number of ways,” he said. “The sensitivity analysis would explore these two extreme ends of where the projections suggest the future might be, so we would develop two more scenarios of future climate at the 2070 time horizon that explore an extreme warming, extreme drying condition and a very minimal warming, extreme wetting condition. Under less warming, wetting conditions, there are certain projects that would probably provide a lot of benefits under a scenario like that, so we want to explore that.”

The sensitivity analysis would give two more data points out at 2070 late century that would give a sense of how these projects could perform in a very extreme future.

The sensitivity analysis would give two more data points out at 2070 late century that would give a sense of how these projects could perform in a very extreme future.

“If you get a project that looks like this, where under the wetter, cooler scenario they don’t really provide that much more benefit, but under the hot, dry scenario, their benefit really decreases, we would classify that as really low resiliency versus a project; if the benefits don’t fall off that much under a hot dry scenario but under a cool, wet they can really do something for us, we would consider that a higher resiliency type project. The project proponents can explain maybe how they would adapt their operations or change their operations to take advantage of this more extreme climate should we get that kind of outcome, so we get a lot more information about how the project is adaptable.”

Mr. Schwarz said that with all this information, they think the Commission can make a risk-informed decision. “All the projects are going to have to analyze the same conditions, which is going to make the comparisons much more fair; they have to do the same assumptions so different applicants cannot make different assumptions that are more beneficial or less beneficial for their project. The net present value of the project is calculated over the life of the project using the best available tools for projecting future conditions. Again, we know this isn’t exactly what these things are going to be worth, but we think this gives a good idea of the trajectory, the direction, and the magnitude of potential change. Future benefits are less certain, and those benefits are discounted so that they are less important than the near-term benefits. If a project can provide benefits right away, that’s better.”

Mr. Schwarz said that with all this information, they think the Commission can make a risk-informed decision. “All the projects are going to have to analyze the same conditions, which is going to make the comparisons much more fair; they have to do the same assumptions so different applicants cannot make different assumptions that are more beneficial or less beneficial for their project. The net present value of the project is calculated over the life of the project using the best available tools for projecting future conditions. Again, we know this isn’t exactly what these things are going to be worth, but we think this gives a good idea of the trajectory, the direction, and the magnitude of potential change. Future benefits are less certain, and those benefits are discounted so that they are less important than the near-term benefits. If a project can provide benefits right away, that’s better.”

“The sensitivity analysis provides us a measure of the resiliency of the project in future conditions,” he said. “We know that the lane we’re in is ending and we can’t rely on historical climate to be a good marker of what these projects need to deal with in the future and we have to do something else. We hope that this approach allows us to identify where we can take advantage of potential opportunities with future climate and arm ourselves against the really devastating impacts that are potentially out there.”

The Commission then paused for stakeholder comments. Commenters were generally supportive of analyzing climate change, but they did express concern over the timeline and the CalSIM modeling: many project proponents do not have access to modeling expertise; many commenters note that having the CalSIM models is not as easy as it might seem and that still much work is needed to make the results usable.

Commissioners discuss. Mr. Gutierrez notes that the climate change analysis is not necessarily for understanding the viability of the projects. “We’re trying to do a baseline comparison, that’s all we’re trying to do, and what we need to argue and debate is, is it worth going through all these steps to give you an understanding of what climate change is going to do. We all have to remember we’re actually investing $2.7 billion over the next several years. That’s a lot of money, we really should pay attention somehow, someway, of what climate change is going to do in the future.”

Mr. Gutierrez is looking for a direction from the Commission. Should they continue moving in this direction? “We can’t think of too many other ways to consider climate change than what we’ve done. We’ve made it simplistic in some ways … We think we are as complex as we need to be, the question is do we pull back, are we going in the right direction?”

The Commissioners discuss; some express concern for smaller projects, but Commissioners are in agreement with staff’s direction.

PEER REVIEW

David Gutierrez then turned to the issue of peer review. He reminded the commissioners that the applicants would be doing a lot of evaluations to determine what their project benefits are, and those evaluations will be reviewed by Commission staff, the Department of Water Resources, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the State Water Resources Control Board, who will all be doing independent evaluations. “During previous Commission meetings, we’ve heard from both sides of the coin as to whether we should or shouldn’t have a peer review,” he said. “At the June Commission meeting, staff talked about their recommendation not to include a peer review, and I will start off by telling you that’s the continued recommendation of the staff.”

Mr. Gutierrez identified several reasons for this recommendation. “First of all, it is not required by law, but more importantly, we believe we have enough checks and balances already: the applicants are going to be doing an evaluation, the staff are going to be doing a check on that evaluation, all the staff have their executives who will be reviewing that staff’s evaluation, and then on top of all of that, we’re going to be coming to the Commission where in a public process, the Commission will evaluate what the staff did, so it’s our opinion that we have enough checks and balances on that. It would really be against the streamlining process if we were to add a peer review process.”

Mr. Gutierrez noted that it was brought up at the June Commission meeting that perhaps the Commission should use a process similar to the process at Cal EPA; however, their peer review process really has nothing to with grant applications. “When any state agency is developing policies, procedures, and in some cases regulation, but specifically on technical issues where we’re actually trying to identify the limit of a particular technical parameter, that specifically requires a peer review and we do that all the time. We have to give credit to Cal EPA, they actually have a very formal process to do that. It’s actually part of the law; any time they develop a regulation, they are required to go through that methodology and it’s required by Health and Safety Code 57004 for the development of their regulations.”

“This is a well developed policy and procedure that they have, so they have years-long contracts with the UC system,” he continued. “It’s important to get an independent peer review, so they don’t even hire the reviewer; they hire the UC system to hire the peer reviewers, and so it’s very independent. However, they don’t do that for their grant package; that’s not where they apply it, and that’s actually what we’re talking about here today.”

Mr. Gutierrez said that doing a peer review on a particular grant application would be unprecedented. “We looked as far as we can and we didn’t find state agencies that did peer review on selection of the actual grant rankings, and so with that, we’d like to move forward without putting in a peer review and we wanted to bring that to you.”

The Commission then heard from those in the room. Comments are mixed; one commenter wants the peer review process to stay in, while the three other commenters support staff’s recommendation to remove the peer review. Commissioners discuss; they are generally supportive of staff’s recommendation.

So with the nod from the Commission on how to move forward, staff will incorporate today’s direction into the draft regulation language. “This doesn’t hold us to the way it’s going to be at all, but this provides us a direction to try and get an alignment so that when you see the regulations, you are not surprised, and hopefully it will just be trying to fine tune regulations the next time you see them,” said Mr. Gutierrez.

OVERVIEW OF THE WSIP TECHNICAL REFERENCE DOCUMENT

Program Manager Joe Yun then gave a brief overview of the upcoming technical reference document, a lengthy document about 400 pages long that is intended for technical staff preparing the application to assist with the quantification, monetization, and the economic analysis of the public benefits.

“The technical reference document is set up to follow the framework that’s in the quantification regulations,” he said. “It’s meant to provide specific information to applicants regarding technically sound analysis, and it describes models and methods that can be employed by the applicant to meet the regulatory requirements of Water Storage Investment Program.”

Mr. Yun then gave a brief overview of the different sections:

Section 1 – Introduction: This section contains background information as well as the limitations of the document. “It is not a prescriptive how to manual for any particular method; it is not meant to be limiting and is not meant to include all possible methods. Applicants are responsible for selecting and implementing appropriate methods for their specific projects. They can use methods that are not in the reference document.”

Section 2 – Defining the without-project future conditions: This section describes how the applicant determines the appropriate geographic and temporal analysis and the set of physical and socio-economic conditions and assumptions to describe the future conditions without the project.

Section 3 – Defining the with-project future conditions: This section describes how the applicant should look at the future condition with their projects; it assists the applicant with how they should describe that future condition by additions and modifications to the without project condition based on their project description, operations plan, and other project-related changes.

Section 4 – Calculating physical changes: Determining benefits involves a sequence of modeling and other analysis to link those operations to a physical change, so the reference document provides technical information to applicants to support selection of appropriate methods for quantifying potential project benefits.

Section 5 – Monetizing the value of project benefits: This section provides economic assumptions and describes the methods and tools for monetizing public benefits with an emphasis on the appropriate level of analysis.

Section 6 – Estimate project costs: This section describes important considerations for estimating project costs that will assist the applicant in determining what type of costs they need to include and the appropriate level of detail to support those costs, which is based on the level of design of the project at the time of application.

Section 7 – Comparing costs to benefits: This section will help applicants with analyzing and documenting expected return on investment.

Section 8 – Allocating costs to beneficiaries: This section provides directions on how applicants should allocate project costs to project beneficiaries. Mr. Yun notes that project allocation is important in determining several of the statutory requirements in Chapter 8, and those are reflected in the regulations as well.

One of the commissioners asks why would they would be telling them how to allocate costs. “It’s not telling them how to allocate costs,” responded Mr. Yun. “It’s helping them to allocate costs to meet the requirements of the regulation because in your regulation, you have a number of different parameters, they have to break things up into public non-public, 50% ecosystem benefit, so we’re trying to help them pay attention to producing an analysis that meets the requirements of the regulation.”

Section 9 – Determining cost effectiveness: The regulations do include a least cost analysis, so this section assists with that analysis to demonstrate cost effectiveness.

Section 10 – Evaluating sources of uncertainty: This section provides guidance with the uncertainties associated with the assumptions and estimates about future conditions and the associated uncertainties.

Mr. Yun said they were planning to release the draft technical document on August 16th; they are planning three workshops around the state to introduce the documents to the public.

The technical reference document will be incorporated into the regulations by reference. “Those regulations are supposed to come out at the end of August, and then formal comment on the technical reference document is the 15-day comment period on the revised regulations, which is currently scheduled in mid-September, so folks would have the technical reference document in their hands for about a month prior to that public comment period. It doesn’t prevent anyone from sending us comments prior to that, but that’s when the format comment period takes place.”

For more information …

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!