The Chair of the Air Resources Board addresses the Southern California Water Committee on the potential ways the water sector can team up with the energy sector to reduce both water and energy use

The Chair of the Air Resources Board addresses the Southern California Water Committee on the potential ways the water sector can team up with the energy sector to reduce both water and energy use

The water-energy Nexus is becoming a hot topic throughout the U.S.; but especially here in California where a multi-year exception drought have reduced California’s surface and groundwater supplies to critical levels.

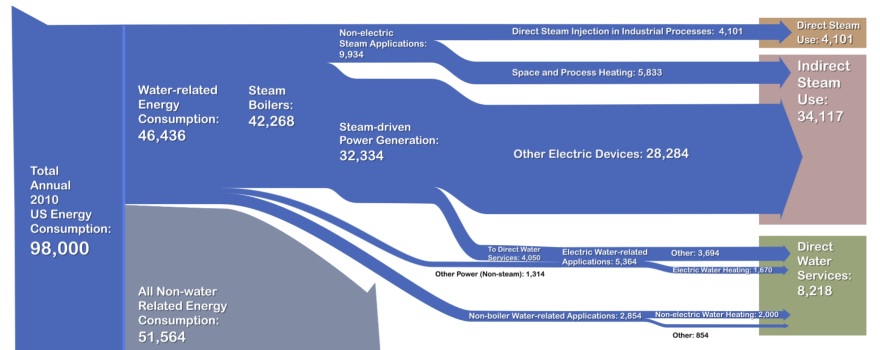

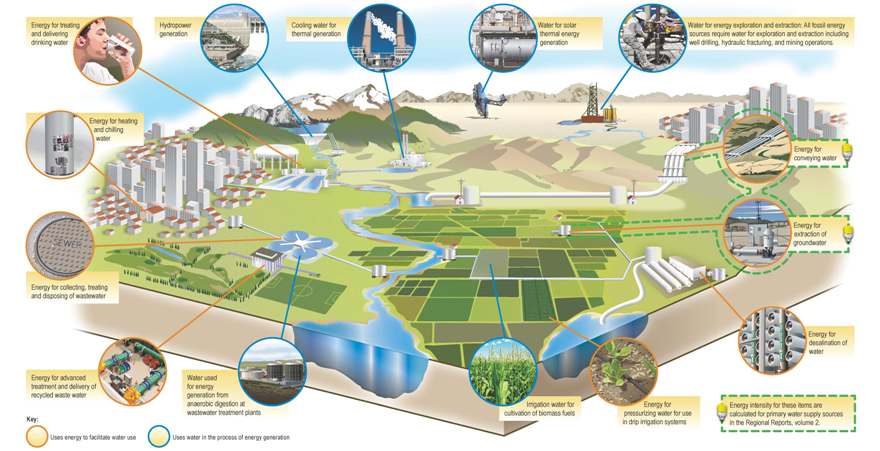

Water use and energy use are inextricably intertwined. The extraction, treatment, distribution, and use of water followed by the collection and treatment of wastewater require a lot of energy; likewise, the production of energy—particularly hydroelectric and thermometric power generation— requires a lot of water. In California, this water-energy relationship is significant: water-related energy use consumes 19% of the state’s electricity, 30% of its natural gas, and 88 billion gallons of diesel fuel every year. Facing water scarcity and the need to conserve water, does the water-energy nexus an opportunity?

Water use and energy use are inextricably intertwined. The extraction, treatment, distribution, and use of water followed by the collection and treatment of wastewater require a lot of energy; likewise, the production of energy—particularly hydroelectric and thermometric power generation— requires a lot of water. In California, this water-energy relationship is significant: water-related energy use consumes 19% of the state’s electricity, 30% of its natural gas, and 88 billion gallons of diesel fuel every year. Facing water scarcity and the need to conserve water, does the water-energy nexus an opportunity?

A recent UC Davis study that found that the energy savings from the mandatory conservation requirements and the resultant water conservation that occurred June 2015 through February totaled 922,543 megawatt-hours — enough to power 135,000 homes for a year.

The pum ps that push the water over the Tehachapis and into Southern California consume the most electricity in the State Water Project system, accounting for 45% of the SWP’s power use, so the potential for reaping benefits of reducing both energy use and water use as well as reducing greenhouse gas emissions could potentially be significant. Given this potential, the Southern California Water Committee recently held a workshop focusing on the water-energy nexus. The keynote speaker was Mary Nichols, chair of the California Air Resources Board.

ps that push the water over the Tehachapis and into Southern California consume the most electricity in the State Water Project system, accounting for 45% of the SWP’s power use, so the potential for reaping benefits of reducing both energy use and water use as well as reducing greenhouse gas emissions could potentially be significant. Given this potential, the Southern California Water Committee recently held a workshop focusing on the water-energy nexus. The keynote speaker was Mary Nichols, chair of the California Air Resources Board.

Here’s what she had to say.

“We are in a very interesting time. I know people who work in the field of water in general tend to have a very long view. I don’t think it’s very often that you hear words like ‘innovative’, ‘flexibility’, ‘change’, associated with the world of water. I hope that doesn’t come as a great shock to you all, but the perception among those who work in the environmental field is that water is probably one of the areas where you have the most entrenched interests, the most entrenched views, and the most difficulty getting people to seek change. I think that’s just absolutely wrong, and one of the things I want to go back and talk to people about is the amount of change, innovation, and interest that I see and hear about going on in this particular sector.”

“I have the opportunity, as the head of the agency that was given the assignment of putting the state’s climate program together, of having an overview of the state. Every part of it – every place, every sector of our economy, every part of our wonderful and diverse mix of natural resources – every one of these areas is both touched by and is a contributor in some way or another to climate change.”

“I have the opportunity, as the head of the agency that was given the assignment of putting the state’s climate program together, of having an overview of the state. Every part of it – every place, every sector of our economy, every part of our wonderful and diverse mix of natural resources – every one of these areas is both touched by and is a contributor in some way or another to climate change.”

“It’s exciting but also daunting to realize we in California are now in a place, because of legislation and because of the commitment of the two governors, the past governor as well as the current governor, where people in every area see climate change as the kind of overarching issue that everything else fits within in some way or another. It may not be the thing you spend most of your time thinking about or working about in any given day, but if you look at the agencies that are addressing anything related to energy, the economy, transportation infrastructure, and water of course, there has become this recognition that we are all operating at a time when climate change is something that we have to consider in everything that we do; if we don’t, then somebody else is going to bring it up in the context of a CEQA lawsuit or some other forum, but the fact is that most people have already incorporated this kind of thinking already in what they do.”

“I think of this a lot when I’m in the position to be talking about or making decisions and recommendations about what to do with the funds that have come to the state as a result of our cap and trade program because probably that is the single element that has attracted the most interest worldwide – just the fact that we created and implemented a cap and trade program, but of course it’s primarily the fact that there now as a result of the fact that a small portion of the auction of the allowances that were created as a part of this program get auctioned, the revenue comes to the state at a time when especially a couple of years ago, there were no new sources of revenue to do good things. It became suddenly my awesome and scary responsibility to preside over the greenhouse gas reduction fund and to try to make sure that the monies that are in that fund are spent in ways that get the most benefit, for not only our ongoing efforts to address climate change, but also that they have as many multiple benefits as possible.”

“I know that one of the things that initially made people in the water sector interested in hearing from me is the existence of the greenhouse gas reduction fund and how we could potentially access more of those funds to do the kinds of things that you all would like to see happen that will help us get to more sustainable water supply and demand in this state and to help to facilitate some of the kinds of transitions that we know need to happen.”

“The problem that I have had in this area, to be honest with you, is that a lot of the focus has been on quantification, on trying to justify expenditures based on dollars per ton of greenhouse gas emissions reduced or to be spent on somehow demonstrating that this water energy nexus, which we all intuitively know exists, is actually real when it comes to trying to do anything in particular that might save energy or save water. It’s relatively easy if you’re talking about changing the fuel supply for pumps or changing the emissions profile through greater efficiency or reuse or recycling of water in wastewater treatment, for example; it’s pretty easy to track the flow of carbon and where it goes and what happens with the water. It’s not so easy and there are still a lot of questions when it comes to trying to model what happens if you reduce the amount of water that’s imported into an area, like Southern California, through greater efficiency and other alternatives, and then say, therefore you have saved that water or saved that energy that would have sent the water there because the fact is we don’t see that happening. We have no way, at least in our little bureaucratic world of saying that that water didn’t go somewhere else, because every bit of water that we use in this state goes somewhere. Every bit of water we have is being used by somebody and so it’s a question of is it better that it got used closer to the source? Well, from an environmental perspective it may well be, especially if it goes to maintain other landscape values that we have.”

“We know instinctively that conservation is good, and I would never argue that it’s bad; I’m just not sure that focusing on that issue is necessarily the place that’s going to get us to where we all want to go, which is a more sustainable system of using the resources that we have, and thereby helping to make California both more energy and environmentally resilient and also reducing our overall impact on the planet. We clearly need to stabilize emissions. We clearly need to show that we can incorporate climate thinking into our work. But I think we have to try to build on some of the policies that we first started articulating back when we began working on the original scoping plan.”

“We know instinctively that conservation is good, and I would never argue that it’s bad; I’m just not sure that focusing on that issue is necessarily the place that’s going to get us to where we all want to go, which is a more sustainable system of using the resources that we have, and thereby helping to make California both more energy and environmentally resilient and also reducing our overall impact on the planet. We clearly need to stabilize emissions. We clearly need to show that we can incorporate climate thinking into our work. But I think we have to try to build on some of the policies that we first started articulating back when we began working on the original scoping plan.”

“There are a lot of areas that need attention quickly. We’re now working on a scoping plan that deals with how we’re going to get to our climate targets for 2030, 2040, on into 2050. There are things that we need to be doing today if we’re going to have a reasonable shot at keeping our emissions triggering the same kinds of thresholds that we’re trying to work with entities on the globe on, which is to keep the temperature rising about 2 degrees centigrade and to hopefully keep it below 1.5. It’s not clear at this point if that’s even possible anymore but we’re definitely very close to that kind of a tipping point.”

“However, there’s a need to act now based on things that won’t really come to fruition certainly until long after I’m out of the office and we need to know right now that we’re on the right track. We haven’t always been able to figure out what the right way is to deal with some of the challenges that are also our greatest opportunities to make changes quickly.”

“For example, methane is a far more potent climate pollutant than carbon dioxide. Methane comes from a lot of places, but certainly forestry, agriculture, waste, water treatment – these are all big sources of methane. But we have very little in the way of regulation and tools for dealing with them. Sometimes it’s because the emissions are harder to measure or to quantify. Often times, it’s because there isn’t any easy point of regulation. You don’t know exactly who it is who should be responsible for doing the reducing. There may not be any obvious ways to find somebody who’s able to pay to get these benefits that we see out there from capturing methane.”

“Probably the most obvious case is forest practices and the need to manage our forests so that they can not only store carbon for years to come, but to reduce wildfire and the emissions of smoke and black carbon which are very harmful, both on a short-term immediate basis to people who are near a fire, but also the slightly longer-term damage those emissions are doing to the atmosphere. We need to get them back into shape where we can enjoy them for their recreational benefits, habitat, and the ecosystem services it that forests provide in terms of water retention, and yet we have no way at this point of really socializing the cost of those fires or of creating a kind of program for managing our forests that would restore them to some kind of health. With every passing day, the actual conditions in our forests are getting worse because of drought and insect infestations; the pictures that you can see in many places of dead trees throughout the Sierra and Northern California are appalling. Mostly we just try not see it or think about it.”

“There aren’t any very simplistic solutions to these problems. I don’t want to be only giving you downbeat news, but I think it’s important to realize that it’s a water-energy nexus, it’s also a water-energy-food-soil-climate-economic nexus that we have to be considering, and there’s probably other things that need to be brought into that balance. We have to think about how we get the most out of our increasingly limited oversubscribed supplies while at the same time, reducing emissions and supporting of a quality of life into the future that we all would like to see.”

“Do we really have the ability to say that if I take out a lawn in Los Angeles and replace with a lovely rock garden, that someone else is going to be able have an orchard so I can buy almonds to use, or for a manufacturing facility in some other part of the state? If we use compost to make soil heathier, and that allows water to be more productive, could we do more with that same amount of water? We don’t have a system that really allows for those kinds of trade-offs to be made. If we get to a really sustainable supply and demand balance, we may end up using the same amount of water overall, but we have to figure out how we do it with the lowest possible emissions.”

“Do we really have the ability to say that if I take out a lawn in Los Angeles and replace with a lovely rock garden, that someone else is going to be able have an orchard so I can buy almonds to use, or for a manufacturing facility in some other part of the state? If we use compost to make soil heathier, and that allows water to be more productive, could we do more with that same amount of water? We don’t have a system that really allows for those kinds of trade-offs to be made. If we get to a really sustainable supply and demand balance, we may end up using the same amount of water overall, but we have to figure out how we do it with the lowest possible emissions.”

“One thing we all know makes a difference and is something we can get behind easily and that’s efficiency wherever possible, whether it’s using renewables for pumping or moving or heating or treating water, whether appliances can do the same job with less amount of water – these are the obvious solutions, and yet even so, we don’t yet really align the incentives with bringing those to market. We’ve had some ability to put funds towards underwriting the cost of some of these kinds of appliances or technologies, but it’s nowhere nearly enough to actually change the way things work.”

“The challenge is to work on the accounting system, but not let the accounting system drive the whole conversation. We need to be looking at the things that make sense to do anyhow from an overall sustainability perspective, and then add in as much as we can the consideration of how it affects climate change and a clean energy future at the same time, because it really is all about sustainability and not just the water and energy nexus.”

“I think that we at the Air Resources Board about how the water system works in the state of California have learned a lot since we first started working on AB 32. It’s way complicated and very, very different depending upon where in the state you happen to be. There is the need for the regulatory system to do more to encourage innovation and to highlight the good things that are going on, because I think that there’s a need right now in particular to be able to just simply capture the essence of some of these exciting developments that are going on.”

“I do want to commend this group for is just having created the Southern California Water Committee and this workshop because to the extent that you come together, not only talk to each other and educate yourselves, but also are supporting other activities that reach out into the community that isn’t part of the water world, you are already doing something important when it comes to building support for the kinds of sensible innovations that are what it’s going to take to achieve our climate goals.

“As a state, we have very ambitious long term goals. We’ve put ourselves on par with nations of the world, and we’ve already done a lot to get there. We’re certainly going to make it to our 2020 goals of rolling back emissions to 1990 levels, but those are going to come mostly through changes in vehicle emissions, and through changes in the electricity supply that were relatively easy to measure and to capture. The next stage, which is involving so much more broad based pervasive activities, such as water supply, water management, water use are going to be harder, and so we’re going to need everybody’s help.”

“I want to thank you for your commitment and your interest in this issue.”

Audience question: We talk a lot about collaboration. From your standpoint, what’s the most effective way for many of these diverse groups and regulators to work together on these shared goals?

“On an ongoing basis, I think we all need to find ways to create new institutional arrangements – not necessarily to create new agencies of entities so much as to find forums where we can all work together on it on an informal basis to share information and perspectives. I think more and more of what I’m seeing in the world of energy and climate is people just doing things, because they’ve decided it make sense to do them and finding those that they need to have as partners and reaching out to them without waiting around for someone to tell them that they have to do it or that there’s a regulatory requirement. But I think it varies by region; the culture is different in different places. Sometimes it’s through a county water task force, sometimes it’s going to be through the utility, either the energy or the water utility of the two of them getting together, and sometimes it may be through some private entity, but however it is, the more diverse the group the stakeholders, the more challenging, but ultimately the more solid the decisions are going to be.”

Question: Is there a role for the private sector to play? Where do you see that role and how do we encourage more of that private investment to fill in as there are limited public resources?

“There are so many anecdotes out there of public-private partnerships or attempts at public-private partnerships, some of which have succeeded and many of which have not. There are different cultures involved; government tends to be much less willing to take risks, much less willing to take risks, much more wanting to see certainty up front. The people who come to our proceedings want us to go slow so they have all the opportunity in the world to weigh in on every issue that they are concerned about, whereas the private sector knows that time is money and they can’t wait forever for decisions to get made. Bringing these two things together, I wish I had a formula I could give you … The state’s cap and trade program which relies on a very complicated market based system still has enemies and there are still people who are very questioning about it, but we now have the evidence that shows that it can work, and that private entities can manage a lot of the pieces of it and monitor it and participate in a independent third party market, and that we don’t have scandals and abuses. What we have are measured results that we are reducing emissions, so I think my main argument on that would be that you need evidence to show that this is just not theory that it actually works, and I think we’re amassing that kind of evidence.”

Question: Considering now with the closure of San Onofre and now the announcement about Diablo Canyon, so taking the nuclear generation component away from the state, does that make the job easier, harder, given the carbon output?

“The two happen to be our only two in-state nuclear generating facilities so they are compared with each other, but the circumstances of their going out of the energy mix. Unfortunately, San Onofre was not a well planned for closure; it was not the intent of the company to take it out of Commission when they did and it required some real scrambling to try and cover those losses. There were certain areas that had a very hard time getting enough electricity in to a locality without that central baseload plant being in place. We have managed as a region to make it through and considering how challenging the weather has been the last few years, it’s really remarkable. It was through enormous effort and frankly a lot of flexibility on the part of various regulatory agencies as well.”

“The way that PG&E is approaching the shutdown of Diablo Canyon is very different. They’ve given themselves 9 years to work on this problem, and they’ve made certain commitments up front about not only where they are going to get the alternative supplies form but also how they are going to deal with workers and communities and that which I think is also important. They did the studies before they announced the decision to convince themselves that they had an economically viable way to supply the electricity that would not increase the amount of carbon, and that from my perspective, of course, is the number one problem. … We can help our whole region if we can do a better job of managing the grid, so we’ll be in a better position to have the electricity when we need it and also be able to share it with others in the future, so I’m pretty bullish on this decision. Of course it’s now got to be implemented and paid for but it starts off in a very good way.”

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!