Details on the progress of the regulations from updates at both the Delta Stewardship Council and the California Water Commission

Details on the progress of the regulations from updates at both the Delta Stewardship Council and the California Water Commission

The California Water Commission is the designated agency to award $2.7 billion of Prop 1 funding for the public benefits of water storage projects. Since the passage of Prop 1, the Commission has been working on developing the regulations for the Water Storage Investment Program.

At the June meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, Mr. Joseph Yun from the California Water Commission updated the Council on the storage program’s statutory requirements, program status, and a summary of received concept papers for potential storage projects. At the June meeting of the California Water Commission held a day earlier, Mr. Yun discussed the possible changes to the draft regulations with the California Water Commission. This post will cover both of these meetings.

DELTA STEWARDSHIP COUNCIL: UPDATE ON THE WATER STORAGE INVESTMENT PROGRAM

At the June meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, Joe Yun, interim acting program manager for the Water Storage Investment Program, updated the Council on where the California Water Commission is in the process of developing the program.

“Where we are right now is that we have some draft regulations that have been out since January,” Mr. Yun began. “We have received comment on the quantification regulations and we are working on changes. The pieces that have not come out yet are things like the evaluation criteria, and so what I’m presenting follows along the lines of the statute in terms of what’s being required by statute, and what we create in the program is driven by that. We have put out a call for concept papers, and so we can get an idea of what projects people are thinking about, bringing into the program.”

“Where we are right now is that we have some draft regulations that have been out since January,” Mr. Yun began. “We have received comment on the quantification regulations and we are working on changes. The pieces that have not come out yet are things like the evaluation criteria, and so what I’m presenting follows along the lines of the statute in terms of what’s being required by statute, and what we create in the program is driven by that. We have put out a call for concept papers, and so we can get an idea of what projects people are thinking about, bringing into the program.”

Chapter 8 of Proposition 1 continuously appropriates $2.7 billion to the Commission for public benefits associated with water storage projects that improve the operation of the state water system, are cost effective, and provide a net improvement in ecosystem and water quality conditions. The Commission can only provide funding for public benefits, which is described in the statute as ecosystem, water quality, flood control, emergency response, and recreation. “You will notice that water storage is not on that list,” Mr. Yun pointed out.

The statute defines storage projects that are eligible for funding: CalFed surface storage projects, groundwater storage projects, groundwater contamination prevention or remediation projects with storage benefits, conjunctive use projects, reservoir reoperation projects, and local surface water storage and regional water surface storage projects.

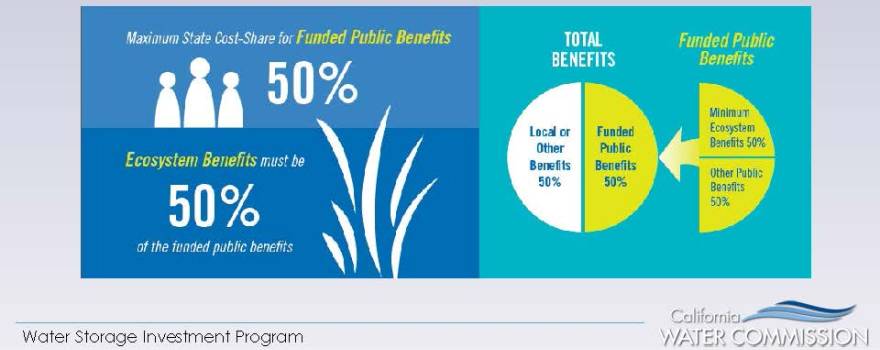

The statute also puts limits and conditions on the funds that are awarded. Mr. Yun explained the complex details: “The maximum state cost share for the funded public benefits can only be fifty percent; we can’t give more than 50% of the total project cost,” he said. “Of the portion that we’re funding, 50% of that public benefit has to be for ecosystem benefits. The statute also states the project must be cost-effective, provide net improvement in ecosystem and water quality conditions, provide measurable ecosystem improvements to the Delta or tributary, and be consistent with the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.”

The statute also puts limits and conditions on the funds that are awarded. Mr. Yun explained the complex details: “The maximum state cost share for the funded public benefits can only be fifty percent; we can’t give more than 50% of the total project cost,” he said. “Of the portion that we’re funding, 50% of that public benefit has to be for ecosystem benefits. The statute also states the project must be cost-effective, provide net improvement in ecosystem and water quality conditions, provide measurable ecosystem improvements to the Delta or tributary, and be consistent with the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.”

The language of Proposition 1 requires that the Commission consider the priorities and relative environmental values for the public benefits that will be provided by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the State Water Quality Control Board.

The language of Proposition 1 requires that the Commission consider the priorities and relative environmental values for the public benefits that will be provided by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the State Water Quality Control Board.

Mr. Yun acknowledged the list is pretty lengthy, so he instead summarized. “From the Department of Fish and Wildlife, their priorities are very Delta-centric,” he said. “There are 8 flow and water quality related priorities, and 8 physical process and habitat priorities. Examples are things like provide cold water at times and locations to increase survival of salmonid eggs and fry, provide flows to improve habitat conditions for in river rearing and downstream migration of juvenile salmonids, provide flows that increase dissolved oxygen and lower water temperatures to support anadromous fish passage, and enhance the frequency of floodplain inundation to enhance primary and secondary productivity and the growth of survival of fish.”

“From the State Board, they have 9 priorities; two related to Delta hydrograph patterns and reduced Delta demand,” he continued. “Examples of those are to achieve Delta tributary stream flows that resemble the natural hydrograph patterns or other functional flow regimes that have been demonstrated to improve conditions for aquatic life, and to reduce current or future demand on the Delta watershed by developing local water supplies and improving regional water self-reliance.”

“Each agency went forward and supplied some criteria by which they would use to figure out if the claimed benefits of a project matched their priorities, so in our regulations, there is criteria that each agency has put out that says states the criteria that will be used to figure out what the relative environmental values are of the projects that have been submitted,” Mr. Yun said. “Those criteria include the number of priorities that the project actually hits, the magnitude and certainty of the improvement, and the spatial and temporal scale of those benefits or where they occur in terms of size and space and when they occur in terms of timing.”

“Among the criteria is the inclusion of adaptive management and monitoring programs that include measurable objectives, performance measures, thresholds, and triggers,” he said. “This is very important because as we look at projects and are getting projects on the front and things can be rather conceptual and you have a lot of proven pieces because you haven’t built anything yet, but once those benefits come into play, likely with changing conditions you will have to adaptively manage those benefits and how you achieve them.”

“Also among the criteria is the immediacy of ecosystem improvements or how fast does the project make improvement actions and how quickly does it realize benefit, the duration or how long will those improvements be in play, consistency with species recovery plan which is specific to the Department of Fish and Wildlife and then there’s an analogous one for the State Board. Location and connectivity is something that Fish and Wildlife is looking at because they are looking at how does the benefit and the improvement actually connect areas that need to be connected in terms of wildlife migration or does it provide a corridor of some sort.”

“Efficient use of water to achieve multiple ecosystem benefits,” he said. “I think both agencies have something they would like to look at and say how many benefits are we getting from that project in terms of, and it’s a simplistic way to think of it, but how many benefits does that drop of water as it goes down the system give me. And then resilience, looking into the future and saying what is the resilience of this project to maintain those benefits, given the changing conditions in the future.”

Before funding can be awarded, the Commission must find that the project is feasible, the project advances the objectives of restoring ecological health, the project improves water management for beneficial uses of the Delta, and the project is consistent with applicable laws and regulations.

“I put all those slides together to show that here’s what the regulations are telling us we must do, here are some of the things that the Commission must find, here’s where the agencies priorities are being considered, and together when we get to the criteria of how we look at a project, we have to gather the information that will allow us to do all those things,” Mr. Yun said.

Councilwoman Susan Tatayon expressed concerns that some projects such as a conjunctive use project might not meet many of those criteria, but if the projects were combined and looked at how they would work together, they would meet many more. Is the Commission looking at that?

Councilwoman Susan Tatayon expressed concerns that some projects such as a conjunctive use project might not meet many of those criteria, but if the projects were combined and looked at how they would work together, they would meet many more. Is the Commission looking at that?

“We’ve been out in front of stakeholders trying to work on the process for about a year, and the notion of integration and how do we get to the pieces that you’re talking about into the program,” he said. “Part of the reason why we wanted to start working with concept papers is to give applicants a chance to see what’s out there and to reformulate or connect projects if they are able to do that. The other notion that we’ve been playing with is how do you even look at integration, not that you would force projects to come together through this process, but how can we allow that opportunity. We do run into some issues with the way the code is written, in terms of making set asides. We’re trying to work with it, but how it manifests is yet to be written and put out.”

“I think some folks are already doing this,” he said. “We’ve been trying to send the message that yeah, there’s a lot of stuff the code requires here, and I do believe some of the projects out there are starting to talk with one another and trying to identify ways that they can start looking at integration with their projects.”

Chair Randy Fiorini asks with the conditions requiring linkage to the Delta and the tributaries, have you developed a map to visually describe areas of eligibility and areas will not be eligible, or are there creative linkages that would make much of the state eligible?

Chair Randy Fiorini asks with the conditions requiring linkage to the Delta and the tributaries, have you developed a map to visually describe areas of eligibility and areas will not be eligible, or are there creative linkages that would make much of the state eligible?

“I believe the way that we defined some of the terms in our regulations, much of the state is eligible,” he said. “There will be pieces that aren’t connected to the Delta. Work on the Trinity I don’t think would be part of this, for example. When we were starting to put the regulation language together, we vetted a lot of stuff with stakeholders to say what does this mean, and so I think we’ve tried to define things fairly broadly. I think the difficulty with measurable ecosystem improvements on the Delta or tributaries, you will always run into that issue of direct connection, proximity and if you’re not, how do you show that you not taking water from the Delta and using groundwater from a bank, how does that measurably show an improvement, and you have a direct causal effect. So I think there are some challenges with what’s been written and how we do that, and we’re still trying to puzzle through some of those pieces.”

The Commission has received 41 concept papers as of March 31st; they are still accepting concept papers and have received an additional concept paper since then. The concept papers are available on the Water Commission website. Thirteen of those concept papers seemed to have eligibility issues, such as the concept paper indicated an ineligible applicant, ineligible project type, or project did not provide ecosystem improvement benefits. Commission staff has communicated with those who have submitted them about the potential ineligibility issues so they can be corrected before the project is submitted. This leaves 28 eligible concept papers.

The Commission has received 41 concept papers as of March 31st; they are still accepting concept papers and have received an additional concept paper since then. The concept papers are available on the Water Commission website. Thirteen of those concept papers seemed to have eligibility issues, such as the concept paper indicated an ineligible applicant, ineligible project type, or project did not provide ecosystem improvement benefits. Commission staff has communicated with those who have submitted them about the potential ineligibility issues so they can be corrected before the project is submitted. This leaves 28 eligible concept papers.

Of the 28, the breakdown is such: 29% regional surface storage, 18% conjunctive use projects, 18% groundwater storage projects, 14% reservoir reoperation projects, 11% groundwater contamination projects, and 11% CalFed projects. Claimed public benefits in the concept papers included Delta ecosystem benefits, flow improvements, Delta outflow, water quality improvements, decreased fish entrainment, habitat improvements, flow, water quality, and habitat improvements in tributaries.

Of the 28, the breakdown is such: 29% regional surface storage, 18% conjunctive use projects, 18% groundwater storage projects, 14% reservoir reoperation projects, 11% groundwater contamination projects, and 11% CalFed projects. Claimed public benefits in the concept papers included Delta ecosystem benefits, flow improvements, Delta outflow, water quality improvements, decreased fish entrainment, habitat improvements, flow, water quality, and habitat improvements in tributaries.

Mr. Yun said that because the program is tied to public benefits and water storage is not one of them, they did not ask for storage estimates; the total here is what was volunteered in the concept papers, and not all concept papers disclosed storage amounts.

Storage estimates from the 28 concept papers totaled 9 MAF; 4 MAF north of the Delta and 5 MAF for south of Delta. Mr. Yun gave the caveat that it is a very rough estimate. “Because our program is tied to public benefits, storage is not one of those. We did not specifically ask folks about how much storage they were providing in the concept papers, so if people volunteered that information, I went ahead and included it; if they did not, it’s not there.”

Mr. Yun then presented a slide with the total project costs and requests. “We have $2.7 billion, but after you deduct bond servicing and the operational costs for the program, it’s probably more like $2.5 billion to grant, and our estimated requests is $17 billion,” he said. “A little bit oversubscribed. Cut that down to the 28 concept papers, and we’re still looking at $7.8 billion. There’s going to be way more demand than we have funding for.”

Mr. Yun then presented a slide with the total project costs and requests. “We have $2.7 billion, but after you deduct bond servicing and the operational costs for the program, it’s probably more like $2.5 billion to grant, and our estimated requests is $17 billion,” he said. “A little bit oversubscribed. Cut that down to the 28 concept papers, and we’re still looking at $7.8 billion. There’s going to be way more demand than we have funding for.”

He then presented two pie charts showing funding requests based on project type on the left, and total project costs on the right. (He didn’t explain any more about the slide.)

Next steps for the program:

Next steps for the program:

The Commission is in the formal rulemaking process now. A draft set of the quantification regulations has been through a round of public comments. They are working on the changes and responses to comments.

“There are other pieces of regulation that we need to get married up with the quantification regulations,” he said. “We have a statutory deadline of December 15 for the Commission to adopt those regulations. Working backwards it means this summer is very critical for this program, so July and August are definitely critical points for us to get language out there and start moving this process along.”

“We still need to develop our application form and the pieces that would tell applicants how to submit information. We’re working on a technical reference document that is currently internally draft for the Water Commission, but that technical reference document takes applicants through the different models that are out there that folks can use to do some of the calculations and some of the economic calculations that we’re going to be asking folks to provide for us. It’s really a tool for applicants to help them put together their applications, but that is currently draft. We’ll have a reference in the regulations to that document so that document will be part of that package.”

CALIFORNIA WATER COMMISSION: UPDATE ON POTENTIAL CHANGES TO THE DRAFT REGULATION

At the June meeting of the California Water Commission, interim acting Program Manager Joseph Yun updated Commission members on the work being done on Water Storage Investment Program and the potential changes to the draft regulations.

Mr. Yun began by noting they are still open for receiving concept papers, and in fact, did recently receive another one. He noted that the concept papers are available on the Commission’s website.

Staff has completed the first draft of the technical reference document and is currently reviewing it internally. Staff still needs to deal with how to roll out the information and put it into the regulations, so there’s more work to be done. Staff is also continuing the development of the climate change and sea level rise scenarios and modeling.

“Both the technical reference document and the climate change pieces will be incorporated into the regulations and will become available for review and comment as part of that process of regulation,” Mr. Yun said.

Staff is continuing to develop the scoring and evaluation process, and they are getting closer to having that together, he said. Staff is also working with the Department of Fish and Wildlife and the State Water Resources Control Board on both the relative environmental value and the technical review process.

Mr. Yun then reviewed six potential changes to the quantification regulations based on comments they’ve received, that would reduce time and move the process along. Those changes are summarized here: Summary of Proposed Revisions to the Quantification Regulations

Mr. Yun noted that the Commission held briefings with interested stakeholders recently about the potential changes, and would be providing some of the feedback he heard.

1. Removal of the mandatory pre-application period

“The existing draft regs include a three month pre-application solicitation period and about a two month review time, and so when we look at removing this, there’s an approximately 5 month time savings in the process. The concept papers that we have been accepting and responding to – that process we believe functionally replaces the preapplication process. We’ve been receiving concept papers and we’ve been responding to them; we’ve identified potential eligibility issues in those concept papers, and we’re open to talking with folks who have submitted concept papers, and we feel that we can remove the pre-application process.”

In the discussions they had with stakeholders, Mr. Yun said he thought there was general appreciation for looking at how we might be able to save time in the process. “There were some discussions about if what we’re doing with the concept papers was an adequate substitution. Certainly staff believes so, but that’s the content of some of the discussion we had. Some stakeholders were supportive of the time savings and removing the pre-application process and some wanted to consider what really means a little more.”

2. Removal of the formal peer review

“When we first conceived the peer review process, we said is it going to be hard to find the folks to do the peer review,” Mr. Yun said. “I think there are some Bagley-Keene issues that we were concerned with the peer review process, and individual peer reviewers couldn’t really confer with one another about an application, so the application would be reviewed by a single peer reviewer. Finding the folks to do that and then trying to manage all that is complex and would be burdensome. We have multiple state agencies reviewing these applications, as each state agency has a management review, so are we being too redundant with how we’re doing the state reviews and then having the peer review as well, so the change here is to talk about the removal of the peer review process.”

He said the in discussions with stakeholders, they were rather divided on the topic. “The peer review for some folks is something that the stakeholder advisory committee really wanted to have happen, so at this stage to say we want to pull it out raises a lot of skepticism,” he said. “There are other folks on the other side of that conversation that say it’s a time saver, It’s not in Chapter 8, Prop 1, so let’s move forward and save some time.”

3. Combining of agency priority review and technical review with an Agreement in Principle process

Mr. Yun noted that there are three pieces to this next proposed change: agency priorities which are the relative environmental value pieces from Fish and Wildlife and the State Board; the technical review process; and something called ‘Agreements in Principle’.

“Agreements in principle is a new concept; it is not in the regulations that currently are out there,” he said. “Towards the end, one of the things that an applicant must do is enter into contracts with the agencies that would be managing public benefits: the Department of Fish and Wildlife, the State Water Resources Board, and the Department of Water Resources. You can’t award the funding until those contracts are made, so it happens late in the process the way we’re currently looking at it. We started thinking about what happens if somebody embarks on this long application process, comes down to the very end, and one of those agencies says, ‘that’s nice but we’re not interested,’ what does that do? Can we put something in place that would allow the applicant and the state agency responsible for managing some of the claimed benefits to have a conversation early on in the process, so there was some kind of agreement on some of those claimed benefits and what the agency was looking for. That in turn would help inform the application process and also help inform and speed up the contracting process on the back end.”

Mr. Yun said they were also talking about stacking and making some processes concurrent. “In the process as it is currently conceived, we would do the tech review, and then the agency priority review would come next, and so we’re adding on to the review process or the timeline. Now we start stacking things, so the agency priority review, the tech review, and the agreements in principle would all start and occur concurrently.”

Most of the conversations around these potential changes were focused on trying to understand the concept of what is an ‘agreement in principle’ a little more, and what does it mean to manage a benefit, he said. “Are you attaching this agreement in principle process to a funding decision, so what does it mean if an agency doesn’t want one of those benefits? And what does it mean if the public benefit that we’re proposing isn’t physically managed by one of those agencies and how does that operate? So there’s some questions that we need to work with behind the scenes and flush out more of the details because that’s what people are really asking.”

4 & 5. Addition of Commission review of staff’s determination of benefits; removal of the 60-day ask

“While we were discussing stacking the technical review, agreements in principle, and agency priority review processes, we discussed that at the end of the tech review, we should come out back to the public and say we finished the tech reviews on all the applications; here’s what the staff thinks about the magnitude and the monetization of those benefits, so if staff found things that were not supported or they used the wrong unit value or something along those lines, we would issue a staff-corrected magnitude and valuation of a benefit,” he said. “When we do that, we needed a way for applicants to come back and say, I don’t agree with what staff did, and so in the concept that we’re talking about is that we’ll add in a Commission review that will allow people to appeal to the Commission and say I don’t agree with what staff did, I’ve got backup information or they missed a factor .. so that’s where the Commission review came in.”

“When we did that, we looked at the current process and said, we don’t need the 60 day ask that happens during the technical review for clarification from an applicant because we just put in a process that allows folks to see what staff thought of their magnitude of benefit monetization and is allowing them to appeal what staff did or staff’s interpretation to the Commission as a corrective action,” he said. “With removal of the 60 day ask is kind of saying if we do the Commission review, we don’t need the 60 day ask of applicants for correction that is currently in the regulations.”

Mr. Yun said that in the discussions, folks were okay with letting go of the 60 day ask if there was another appeal process in place. “I think the biggest thing that came out of this conversation was should be the applicant who was requesting the Commission for an appeal to say we don’t like what staff did to our application, and then the discussions turned to, should other people be able to ask the Commission for an appeal, so can your competitor come in and say, no I don’t think that’s what that’s about, or should some other interested party want to say I don’t like what the staff did or I’m not sure about the number.”

6. Provision for funding environmental documentation

The statute allows for funding of completion of environmental documents; the existing draft regulations only talks about permits, not environmental documentation. Staff felt that this was in statute and it aids projects in moving forward, and that there was enough review pieces in place to reduce the risk of sunk costs if early funding for completion of the environmental documents was provided, Mr. Yun said.

“In the conversations that we had, I heard two things,” he said. “Some were supportive of saying if folks needed this, it would be good, and then some folks said they were worried about funding soft costs, when if we held off to construction, we might be able to fund more projects come construction time.”

WHAT LIES AHEAD

Mr. Yun said they were working to roll the evaluation regulations into the quantification regulations so there will only be one set of regulations. Besides the draft regulations, staff is working on the development of the application form and the completion of the technical reference documents.

December 15, 2016 is the statutory deadline for Commission adoption of the regulations.

Commissioners discussed the potential changes, but took no action. More information to come at the July meeting of the California Water Commission.

For more information …

- For more on the Water Storage Investment Program from the California Water Commission, click here.

- To watch this item at the Delta Stewardship Council, click here. This was part of agenda item 9.

- To watch the webcast of this item from the California Water Commission, click here. (Link will be posted when available.)

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!