The farmers achieved a 32% reduction in diversions

The farmers achieved a 32% reduction in diversions

At the March meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, Delta Watermaster Michael George briefed council members on the report on the voluntary reduction program among in-Delta water rights claimants that was in place last summer over the growing season, work being done on salinity hotspots in the Delta, implementation of the new measurement regulations, and a brief update on water rights enforcement actions.

Mr. George began by noting that the hydrology is quite different than last year, largely due to the precipitation in the first two weeks of March. “The northern reservoirs are full, but San Luis is still in pretty bad shape; that’s the big reservoir operated by both projects south of the Delta,” he said. “Notwithstanding the big flows on the Sacramento River, the amount of diversion is still quite limited and that’s of course because the limiting factor is not reservoir storage capacity and it’s not salinity control; it’s the negative flows in Old Middle River. So notwithstanding all the water in the system and it’s substantially improved quality, the infrastructure that we built so long ago and are now asking to serve multiple functions is limited by the way it impacts flows in the south Delta.”

In-Delta Voluntary Diversion Reduction Program

Last year at this time, the state was facing the fourth year of a serious drought and there were threats of the State Board determining there was not sufficient water in the system for all uses, and then having to administer a process of cutting off or curtailing water users based on their water right priorities, Mr. Geroge said.

“A group of farmers in the Central and South Delta, recognizing that there were risks of curtailment and recognizing that the system was in serious stress, came forward and proposed a program,” he said. “I want to emphasize that this program was not started by the office of the Delta Watermaster or the State Board. This was an effort that was brought forth by the farmers in the Delta trying to figure out how to help in managing the stress on the system.”

The goal was to reduce diversions of surface water during June, July, August, and September, the four critical months of the growing season when the Delta and the water system in general is under maximum stress; they would recruit volunteers who would agree to take certain actions so as to reduce their diversions from the Delta by 25% compared to the same four months for the same lands in 2013. “As it was proposed, they said we’ll give the certainty of reduction of demand on the system, but what we want in return is an assurance that if later in the season, curtailments or cuts or reductions to use would be deeper than that, we want some assurance that those deeper cuts are somehow going to be credited for the reductions that we’ve already made,” he said.

The goal was to reduce diversions of surface water during June, July, August, and September, the four critical months of the growing season when the Delta and the water system in general is under maximum stress; they would recruit volunteers who would agree to take certain actions so as to reduce their diversions from the Delta by 25% compared to the same four months for the same lands in 2013. “As it was proposed, they said we’ll give the certainty of reduction of demand on the system, but what we want in return is an assurance that if later in the season, curtailments or cuts or reductions to use would be deeper than that, we want some assurance that those deeper cuts are somehow going to be credited for the reductions that we’ve already made,” he said.

The terms of the program were first that it was voluntary. “No one was required to be a member; every farmer would make an individual decision about whether it made more sense to him or her to join the system to propose a plan to reduce diversions or to take their changes,” he said. “Secondly, we offered enrollment only to those who had previously claimed riparian rights within the Delta, and the reason we limited it to riparians was because riparian water use is place specific, so if you’ve got a riparian water right, you do not have the opportunity or option to transfer the water to another use. It’s unlike an appropriative right, which might if you forbear the use of it, it could be the basis for a water transfer. This was non-transferrable water; it was water that was not going to eligible for use anywhere else.”

The program came together late in the spring; it was rolled out and announced on May 21st and approved by the State Water Board on May 22. “We required that anybody who wanted to participate had to file a plan for how they would meet the 25% reduction by June 1st, so a very short period of time to put those plans together,” he said. “However, we decided that it made sense to let the farmers decide how to meet the objective, so we specifically said the objective is a 25% reduction in diversions of surface water, propose to us how you can, give us your plan on a field by field or group of fields basis, and then no approval is necessary; implement your plan.”

“It was our role to consolidate those plans, to do a verification program, to actually go out in the field and see if this was happening,” he said. “We also required that everyone who was involved in the plan file an after-action report in November, so basically a month after the end of the program, we anticipated required asked those voluntary participants to tell us how did the plan operate. So we did verify, we did get those after action reports, and we issued the report.”

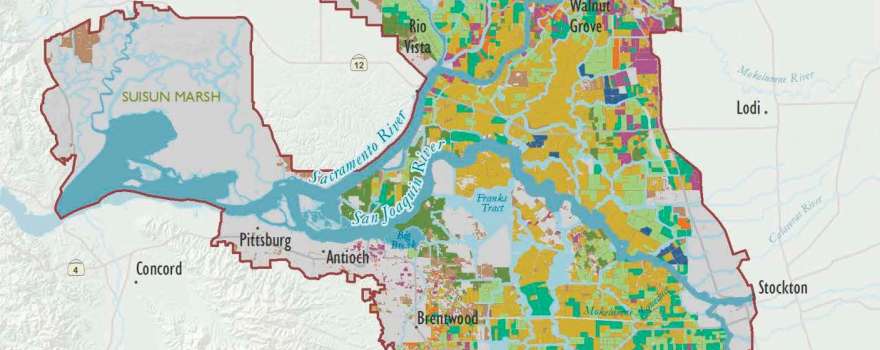

The plans covered 180,000 acres, roughly two-thirds of the Central and South Delta, which was where the shortages were expected to be most acute and where water quality was a big concern; virtually all of the riparian claimants were involved in the program, he said. There were 217 plans that were submitted; many of those plans involved multiple farms, multiple fields, and multiple crops. “Each of them were unique, they were all different and with a far greater amount of creativity and flexibility than we had anticipated,” he said.

The program overachieved its target of 25%; overall diversions were reduced by 32%. “We knew from the beginning that we would not be able to accurately measure the reduction in consumptive use, and what we wanted to do was reduce the amount of water diverted from the surface to irrigate, and then figure out how much consumptive use savings correlates to reductions in diversions,” he said. “So we can’t say for sure what some of these impacts were, but it does appear that the reductions in demand in the Delta likely helped us avert curtailment of riparian rights in the Delta.”

The program overachieved its target of 25%; overall diversions were reduced by 32%. “We knew from the beginning that we would not be able to accurately measure the reduction in consumptive use, and what we wanted to do was reduce the amount of water diverted from the surface to irrigate, and then figure out how much consumptive use savings correlates to reductions in diversions,” he said. “So we can’t say for sure what some of these impacts were, but it does appear that the reductions in demand in the Delta likely helped us avert curtailment of riparian rights in the Delta.”

“We came within a whisker of having curtail water rights at the end of July, but once we got to August, diversion demand goes down pretty substantially,” he said. “That was halfway through the program, and one of the things I’m very pleased about is that once the risk receded, we didn’t see any reduction in the effort in the attempt to meet that 25% requirement.”

“They achieved significant results,” Mr. George said. “Clearly there were some results that were favorable for the projects; it allowed the projects to maintain a little bit more water in cold water storage and reduce the amount of water that they had to devote to salinity management, and it eased the pressure on the system a little bit during those critical four months, and it was all achieved without waiving any rights, without any regulatory burden or process, and without any judges or lawyers very much involved except for negotiating the terms to put it together.”

“When we originally were conceiving this, we thought that most of the savings would come from land fallowing, but that turned out not to be the case; it was a much more creative effort,” he said. “Only about 6,000-7,000 out of the 180,000 acres were fallowed during the program. As it turns out farmers adequately informed and committed to reduced diversions rotated to less water intensive crops. Now maybe a lot of that was already in play before this program ever rolled out; in other words, farmers were already responding to the fact that they feared there might not be enough water so rotated to some less water intensive crops.”

“When we originally were conceiving this, we thought that most of the savings would come from land fallowing, but that turned out not to be the case; it was a much more creative effort,” he said. “Only about 6,000-7,000 out of the 180,000 acres were fallowed during the program. As it turns out farmers adequately informed and committed to reduced diversions rotated to less water intensive crops. Now maybe a lot of that was already in play before this program ever rolled out; in other words, farmers were already responding to the fact that they feared there might not be enough water so rotated to some less water intensive crops.”

“One thing that accounted for a lot of the savings was changes in the irrigation schedules, particularly for alfalfa,” he said, noting that the typical practice is to irrigate alfalfa every two weeks. “We had a lot of people propose to cut that in half and water only once a month. It means they won’t be able to cut the alfalfa as often and they will sacrifice some quality as well as quantity, but they figured they could save a lot of water without entirely sacrificing the crop.”

Between 2013 and 2015, there was also a movement away from furrow irrigation or flood irrigation to more precise subsurface irrigation. “Anybody who made the change from 2013 to 2015 did it before and without anticipation of this particular program, but the program allowed them to take credit for that investment. It’s clear that the investment was motivated primarily by a sense of reduced water availability and by the attempt to improve quality and yields, particularly with respect to tomatoes in the Delta. The quality and the yields are going up primarily because people are making investments in precision irrigation techniques, but they got credit for that.”

Other farmers reconfigured their fields. Mr. George displayed pictures, showing how typically irrigation is on 30” separated furrows, and some farmers went to 60” separations, planting what amounts to every other row. “This turned out to be a pretty successful way to save real water without a concombinant reduction in yield. This is an example of a technique that a lot of farmers were telling us they had heard about but wouldn’t have done had there not been this program. It’s something that will allow us so conserve water even in more average or typical or even wet years.”

Other farmers reconfigured their fields. Mr. George displayed pictures, showing how typically irrigation is on 30” separated furrows, and some farmers went to 60” separations, planting what amounts to every other row. “This turned out to be a pretty successful way to save real water without a concombinant reduction in yield. This is an example of a technique that a lot of farmers were telling us they had heard about but wouldn’t have done had there not been this program. It’s something that will allow us so conserve water even in more average or typical or even wet years.”

The Watermaster’s Office spent the summer cataloging the plans and correlating them with statements of diversion and use, as well as going out and doing field verifications to make sure the plans were being put in place. They visited the larger farms as well as the smaller farms. “Once this program caught on, our inspections were interesting but probably not nearly as effective as peer pressure, because if you’re driving your F150 down a levee road past your neighbor’s place, you can tell whether he’s meeting his plan objectives, and that sense of peer pressure as well as community pride had probably more effect than the members of the Delta Watermaster’s office being out in the field.”

Mr. George then presented the statistical overview, acknowledging that the vast majority of the diversions in the Delta have been unmeasured. “But based on the verification and on correlations with some of the satellite imagery, I’m convinced that this program had significant impact as it was designed to do, but the precision of these numbers is more than the measurement techniques that we’ve got will bear. They are still estimates; they are not precise measurements.”

Mr. George then presented the statistical overview, acknowledging that the vast majority of the diversions in the Delta have been unmeasured. “But based on the verification and on correlations with some of the satellite imagery, I’m convinced that this program had significant impact as it was designed to do, but the precision of these numbers is more than the measurement techniques that we’ve got will bear. They are still estimates; they are not precise measurements.”

The program was open to anybody who had claimed a riparian right, although there were those who said that those who entered the program should be able to prove that. “We didn’t go down that slippery slope; we recognized that these water rights are claimed, and that there are very few adjudicated water rights, and even a smaller percentage of those are in the Delta, so we said no, as long as you had made a good faith claim of riparian rights, we weren’t going to use this program to try and prove up or adjudicate the quality or the back up of that water rights program,” he said. “Neither, however, would we indicate in any future proceeding that participation in this program was any evidence to support that riparian right. There are some big issues that we’re all facing with respect to proving up riparian rights.”

There was also a positive impact on Delta outflow, Mr. George said, explaining that buried in the State Water Board’s D-1641 is a formula to measure outflow that uses a ten year average of water use in the Delta and by the projects. “It became clear in June that that model was out of whack and there was more outflow,” he said. “We started to look into why that was, and the projects concluded that part of it was that there was a reduced demand in the Delta, so there was more outflow than was predicted in the models that allowed the projects to adjust operations accordingly to help maintain salinity, water quality, and keep the system operating, so the program actually did provide a little bit of reduction of stress on the system at a critical time.”

Although the program was successful, it can’t really be repeated year after year because of the salt issues in the Central and South Delta. “Farmers are concerned that if you did this kind of effort every year, you might reduce the flushing of salts that’s necessary to keep the soil productive,” he said. “Now we’re going to get a good flush this year because of the hydrology, but doing this year after year could have that risk to the system.”

Managing riparian and priority curtailments side by side: A conundrum unsolved

We also need improved measurement of diversions as the old way of guestimating is just not accurate enough, particularly when the system is under stress. “It’s okay if there’s lots of water in the system and you can get away with kind of the slobber from imprecision, but when it comes to these kinds of periods which we are likely to face in the future, we’ve got to do better,” he said.

The problem of managing curtailments in side by side riparian and priority systems is a conundrum that we have not solved, Mr. George. “It’s been in the system since we became a state and adopted the common law of riparianism and then added priority system on top of it without ever trying to correlate those two,” he said. “Riparians, when there’s a shortage, share that shortage correlatively; that is, on a proportional basis, so if the natural flow goes down below the needs of all the riparians, precisely what happens in a drought? All the riparians are supposed to reduce their demands correlatively or proportionally to the reduction in the system.”

The problem of managing curtailments in side by side riparian and priority systems is a conundrum that we have not solved, Mr. George. “It’s been in the system since we became a state and adopted the common law of riparianism and then added priority system on top of it without ever trying to correlate those two,” he said. “Riparians, when there’s a shortage, share that shortage correlatively; that is, on a proportional basis, so if the natural flow goes down below the needs of all the riparians, precisely what happens in a drought? All the riparians are supposed to reduce their demands correlatively or proportionally to the reduction in the system.”

The priority system also affects many of the same lands, same owners, and same water rights claimants, but the priority system is entirely different, he pointed out. “It cuts off the junior to give 100% to the next most senior,” he continued. “When you’ve got those two systems in close proximity among similar owners, sometimes with the same crop, depending on both systems, when you try to curtail a priority appropriator, he’s going to point to have you gotten all the riparians to reduce correlatively; and by the way, those riparians only have the right to natural flow while I as a appropriator, have a right to abandoned flows, have a right to wastewater returns, things like that.”

“You all know it is impossible to sort those things out at all, let alone in real time while you’re trying to figure out who should be curtailed, in what order, and by how much,” he said. “This is a problem that’s been baked into our system forever, it’s a problem that we faced when we came within a whisker of having to do riparian curtailments, and I’ll tell you that we in the Office of the Watermaster and our colleagues in the Division of Water Rights had no idea how we would do that.”

“I mention this as one of those things we better learn from so that we can do a better job when this comes to us again,” said Mr. George.

Salinity hotspots

“Over 2015, I received 10 reports by the CVP and the SWP about what they call ‘exceedances of their conditions’; I call them violations of their water rights permits,” said Mr. George. “In any case, there were ten of them. Six of them were focused on a specific hot spot in the Delta down near the federal Jones pumping plant along Old River at the point where Tracy Blvd crosses Old River. It’s a nasty hot spot of high salinity, and we’ve been cooperating with the regional water board to figure out what’s going on and to begin to address it. Even though it’s a complex, long term, difficult problem, we have the Department of Water Resources who just funded a study of cause and potential remedies; we brought in the South Delta Water Agency as well as our office to try and find a solution to the problem, rather than just to correct or discipline the exceedances, which I am calling violations.”

SB 88 Measurement regulation

Last June, the legislature passed and the Governor signed SB-88 which for the first time required measurement of all diversions in excess of 10 acre-feet per year. The implementing regulations were adopted by the State Board on January 19th and the State Board is now working with other water rights users throughout the state to implement the regulations, he said.

Mr. George explained that the regulation is set as a performance standard. “You must measure and report on a relatively frequent basis how much water you’re diverting, and you must do so either with a measurement device that meets that performance standard, a gauge or a meter or some device that will get to a level of precision of plus or minus 10% of actual,” he said. “You have to be able to record that data on a regular basis, and then report it as necessary. Reporting will be more frequent sometimes than other times.”

If a device is not the right way, a measurement method can be developed, he said. “That is a method that you can develop, maybe with a group of farmers who may share a diversion or a distribution ditch, or maybe island wide, but you can come up with a method so long as it hits that performance standard of plus or minus 10%, and we’ll accept the reports based on that method.”

There can be circumstances where neither a measuring device nor a measurement method will achieve that level of accuracy, and this may be especially prevalent in the Delta, so there is a alternative for developing an alternative compliance plan, he said. “It’s not a get out of jail free card – it’s not like prior to SB 88 where people could say, ‘measuring my diversion is not locally cost effective’ – and about 90% of the diversions in the Delta filed reports saying that measuring their diversion was not locally cost effective,” he said. “That’s no longer the case. If you can’t meet the objective through a measurement method or a measuring device, then you go to the alternative compliance plan, and that has certain requirements. Number one, you have to demonstrate why you can’t use the measurement method or measuring device, but then you have to go through a process to say, how close can I get, how can I get closer over time and if there’s a requirement for funding, what is the plan for funding; there is a process for review and implementing that alternative compliance plan.”

Mr. George noted that he is working closely with the Suisun Marsh Resource Conservation District, because the Suisun Marsh is one of those places with neither a measurement method nor a measuring device is going to be accurate as it’s tidally influenced and they are not the traditional kind of diversions. “We’re working on an alternative compliance plan that we hope will be Suisun Marsh wide that each water right holder and reporter within the marsh will be able to sign on to and use as a cooperative way of managing compliance with this new regulation,” he said.

The regulation does not require us to review and approve any of these plans, he said. The water rights holder has the responsibility to meet the objective; the State Board will review plans and reports, do verifications and enforcements where necessary, but won’t be in a position of being inundated with all the plans they don’t have the expertise to review and approve, he said.

Water rights enforcement

Mr. George then lastly turned to the recent cases involving enforcement of the water rights system. There were circumstances in 2015 where the State Board’s Division of Water Rights concluded that there was insufficient supply and people were told their specific priority would not be getting any water, and they were expected to cease diversions. “You can appreciate that challenges ensued, challenges to the board or the watermaster’s authority to make those determinations, whether there is even jurisdiction for pre-1914 water rights,” he said. “There have been claims against our authority, jurisdiction, the quality of our data, and the methodology that we used to determine water availability. All of those cases have now been consolidated and removed; they are going to be heard in Santa Clara County, and all those court actions have been stayed pending a state board process which is underway.”

The day prior to the meeting, Mr. George was in hearings for enforcement actions against Byron Bethany Irrigation District and the Westside Irrigation District. The hearings were suspended because at the end of the State Board’s presentation of the case, a motion to dismiss was made based on the insufficiency of the prosecution’s case; the prosecution failed to present evidence sufficient to support the allegation of unlawful diversion, and so the hearing has been suspended.

“If the cases are thrown out, I hope we get some direction on what we should do instead,” Mr. George said. “I’m hoping that whatever happens, these cases and their development and ultimately appeal to the courts is going give us better tools to use in the future. I don’t care so much whether it’s determined we did things entirely right, but I hope we get some further guidance on how we can do it better.”

“Even as these cases are now in hiatus, we’ve developed a consensus among the regulators and the regulated community that we need better rules of the road,” he said. “We need to understand the system better and we need to have a consistent transparent way of predicting what’s going to happen as shortages set in, so whether these cases continue or whether they get dismissed, I think we have developed a consensus that we at the Watermaster’s office and within the State Board, need to convene an inclusive rulemaking process to develop rules of the road we can apply going forward.”

Lastly, he turned to the Tenaka case which is where the Modesto Irrigation District sued the State Board, and Tenaka, a riparian claimant in the Delta, challenging those water rights. The State Board was dismissed from the case but the case went on and there was a tentative decision issued on February 27th; they are still waiting for the final decision, which will undoubtedly be appealed. “But pending appeal, it will be the law of the case and we intend to implement the law of the case, which essentially found that there was no basis for the rights claimed for this particular parcel,” he said. “That has profound implications for what’s going on in the Delta and we’re going to be challenged to figure out how to incorporate the law of that case and if it is amended or changed or upheld or whatever happens on appeal, that’s an important case for all of us.”

In conclusion, he said it’s important to consolidate what we’ve learned based on the chaos of 2015. “I hope we do have a respite now, but shame on all of us if we don’t learn those lessons so that we can apply them going forward. We’re going to get a lot of litigation that will go on for the next few years, that will inform those decisions, and then hopefully we’re going to develop some of these insights so that we do a better job going forward.”

“So Mr. Chairman, that’s my quarterly report … “

For more information …

- Click here for the Delta Watermaster’s full presentation.

- Click here for the agenda and meeting materials for the March 24th meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council.

- Click here to visit the Office of the Delta Watermaster online.

- Click here for the Delta Watermaster’s report on the voluntary reduction program among in-Delta riparian water right claimants.

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!