Presentation at the California Water Commission looks at how models would be used in evaluating water storage projects for possible funding

At the February meeting of the California Water Commission, Supervising Engineer Jenny Marr gave a presentation to the commissioners on modeling as a tool for water resources planning and decision making with a focus on how models might be used in the upcoming evaluation of projects for the Water Storage Investment Program.

At the February meeting of the California Water Commission, Supervising Engineer Jenny Marr gave a presentation to the commissioners on modeling as a tool for water resources planning and decision making with a focus on how models might be used in the upcoming evaluation of projects for the Water Storage Investment Program.

“Before we dive into talking about the specifics of modeling and analysis, I wanted to make sure that I tied it back to what the Commission has to do,” Ms. Marr began. “Based on statute, the Commission has to make four findings before funding a project: A project is feasible, consistent with all applicable laws, improves water management for beneficial uses of the Delta, and protects or restores ecological health of the Delta.  Also as stated in regulation, the Commission has two decisions: what projects are selected and how much funding they receive, so we have to make sure that the modeling and analysis supports the findings and decisions that the Commission has to make.”

Also as stated in regulation, the Commission has two decisions: what projects are selected and how much funding they receive, so we have to make sure that the modeling and analysis supports the findings and decisions that the Commission has to make.”

Ms. Marr noted that the decision process will occur over a months-long process that includes compiling a preliminary list of projects for funding, making findings by resolution, making an initial funding decision, and then the conditional funding commitment. The decisions and findings will be informed by the technical review; staff will compile the information from applications and then distill the information down to what’s required for decision making. “So it’s important to have an idea of how modeling informs the analysis, what assumptions and limitations there are in getting the information you need to make the decisions and findings,” she said.

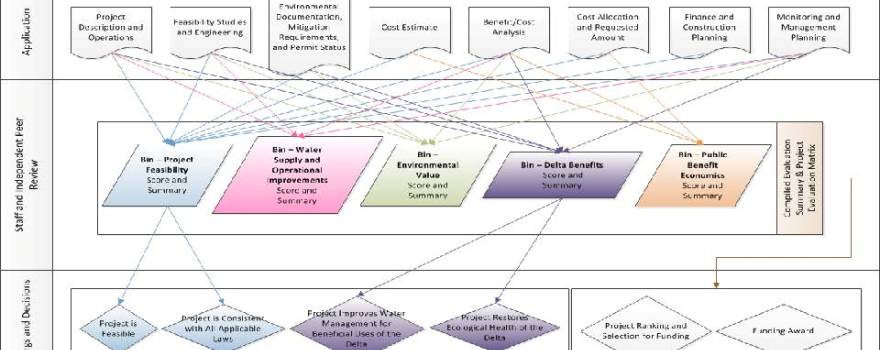

“Knowing that these are the four findings and the two decisions that the Commission has to make, staff has started to organize criteria and metrics into various bins,” she said. “This figure lays out how staff is organizing information: there’s a project feasibility bin, a water supply and operational improvements bin, environmental value, Delta benefits, and public benefit economics. The reasons why we proposed to divvy things up in this way is to directly inform the findings, but to also split up our technical review team by expertise.”

“Knowing that these are the four findings and the two decisions that the Commission has to make, staff has started to organize criteria and metrics into various bins,” she said. “This figure lays out how staff is organizing information: there’s a project feasibility bin, a water supply and operational improvements bin, environmental value, Delta benefits, and public benefit economics. The reasons why we proposed to divvy things up in this way is to directly inform the findings, but to also split up our technical review team by expertise.”

The information will be pulled from the information provided in the project application are articulated in the current set of regulations, such as the project description and operations, feasibility studies and engineering, environmental documentation, mitigation and permit status, cost estimates, benefit cost analysis, cost allocation, requested amount, finance and construction planning, and monitoring and management planning.

Ms. Marr then dove a bit further into the details of how staff will use the pieces of information to use in the individual bins. “For project feasibility, we’re going to be looking at all aspects of a project to determine if it’s engineering and technically feasible, environmentally feasible, economically feasible, and financially feasible,” she said. “We’re using those sub criteria to inform the feasibility of a project so you all can make a finding. Additionally, we recommend looking at the implementation complexity.”

Ms. Marr then dove a bit further into the details of how staff will use the pieces of information to use in the individual bins. “For project feasibility, we’re going to be looking at all aspects of a project to determine if it’s engineering and technically feasible, environmentally feasible, economically feasible, and financially feasible,” she said. “We’re using those sub criteria to inform the feasibility of a project so you all can make a finding. Additionally, we recommend looking at the implementation complexity.”

“For water supply and operational improvements, we’re using specific pieces of information from the applications identified here to inform the water supply and operations and improvements bin. The metrics or criteria could include water supply reliability, water management flexibility, and the resiliency of benefits to changing future conditions.”

“For water supply and operational improvements, we’re using specific pieces of information from the applications identified here to inform the water supply and operations and improvements bin. The metrics or criteria could include water supply reliability, water management flexibility, and the resiliency of benefits to changing future conditions.”

“The next bin is environmental value,” Ms. Marr continued. “That’s the relative environmental value as described in statute for the determination of ecosystem benefit and water quality benefit relative environmental values, so State Water Board and Department of Fish and Wildlife will be using pieces of information from the application to develop scores for these relative environmental values.”

“The next bin is environmental value,” Ms. Marr continued. “That’s the relative environmental value as described in statute for the determination of ecosystem benefit and water quality benefit relative environmental values, so State Water Board and Department of Fish and Wildlife will be using pieces of information from the application to develop scores for these relative environmental values.”

“The next bin is Delta, and Delta tributary ecosystem improvements are really tied to the findings, beneficial uses and ecosystem improvements, and this ties application pieces to how we will inform this bin. These criteria could include the exact language from statue, ecological health, and water management for beneficial uses.”

“The next bin is Delta, and Delta tributary ecosystem improvements are really tied to the findings, beneficial uses and ecosystem improvements, and this ties application pieces to how we will inform this bin. These criteria could include the exact language from statue, ecological health, and water management for beneficial uses.”

“Economics criteria under the public benefits economics category, could include cost effectiveness and return on investments,” said Ms. Marr.

“Economics criteria under the public benefits economics category, could include cost effectiveness and return on investments,” said Ms. Marr.

Ms. Marr then presented the ‘spaghetti diagram’ of how it all comes together. “The top two areas are where staff will be going through the applications, pulling pieces of information, and putting into digestible bins for Commission finding and decision making,” she said. “Our intent is to do some dashboarding, so you’ll have easy to grab information that we pull from the application will include staff feedback to describe these bins so you’re in a position to make these findings and the decisions in a very informed manner.”

Ms. Marr then presented the ‘spaghetti diagram’ of how it all comes together. “The top two areas are where staff will be going through the applications, pulling pieces of information, and putting into digestible bins for Commission finding and decision making,” she said. “Our intent is to do some dashboarding, so you’ll have easy to grab information that we pull from the application will include staff feedback to describe these bins so you’re in a position to make these findings and the decisions in a very informed manner.”

Modeling as a tool to support Water Storage Improvement Program decision making

Ms. Marr began this portion of the presentation with the disclaimer that she herself is not a modeler. “I sit in conference rooms with modelers,” she said. “It’s a very specialized group. I definitely have experienced understanding the assumptions and limitations that go into models, but in my day to day job, I’m not working with them.”

Modeling is a tool that can be used at several points in the process, she said. “Each model informs the next,” she said. “Modeling is kind of a broad term. Modeling can be the most sophisticated, most expensive tool out there you could use, or it’s a spreadsheet model that does some addition and subtraction for you, so we’re using modeling as a broad term.”

Modeling will be important to project applications as it will be used to quantify their benefits, both in physical magnitude and in monetary units, and there are different models for doing both of those, she said. The Commission will use the information from the models to select the projects for funding.

“As decision makers, it’s really important to understand not necessarily the mechanics of the models, but understand the limitations and assumptions that go into these models and how changing those assumptions might modify the results,” she said. “We’re going to require a high level of documentation and justification in the applications where the applicant has to describe, based on the models and assumptions that they used, what the limitations are of understanding the results.”

“There’s a variety of models that are out there, and we really want to make sure that people are using models that are appropriate to their project, location, type, and the level of detail information that they have to the scale and size of magnitude of benefit that they are looking at, and that they are appropriate to the decision that needs to be made,” she said.

Modeling comes into play at a lot of different points, Ms. Marr noted. A guidance document was developed by Commission staff a few years ago on the methods and tools for quantifying benefits; staff are working now on a technical reference document to provide guidance on developing a quality analysis for the other steps.

She then presented a schematic of how a project might be evaluated using various models. “The big blue box in the middle describes different conditions, operations and quality analysis that need to be modeled for various projects,” she explained. “Inputs include datasets of varying variety of quality assumptions based on how the project is going to fit into the system, as well as methods for calculation and other appropriate information for any of these model steps.”

She then presented a schematic of how a project might be evaluated using various models. “The big blue box in the middle describes different conditions, operations and quality analysis that need to be modeled for various projects,” she explained. “Inputs include datasets of varying variety of quality assumptions based on how the project is going to fit into the system, as well as methods for calculation and other appropriate information for any of these model steps.”

“These models are going to result in specific outputs,” she continued. “Most of them are physical changes to your environment, and with that project condition, so they also need to do that step of taking these physical changes and determining if they are positive or negative, benefits or impacts, and then monetizing the value of those physical changes. This complex array of modeling is further complicated with all these sources of uncertainty.”

The Department of Water Resources has guidance for putting various levels of uncertainty or specificity into the climate change and sea level rise analysis, but she acknowledged that making assumptions on operational changes, regulatory changes, economic and technological is a little bit more difficult and a little more speculative.

“We have also included in the regulation some uncertainty analysis on structural changes,” she said. “If they know with some level of certainty various projects that might come online while their project is under operation, we’ve asked them to consider how those structural changes in the environment or in the facilities might change their benefit package.”

With future conditions, they are asking people to look at the existing characteristics of the watershed or water system and what’s going on right now, and then evaluate how do these conditions change in the future, she said. “What are problems, needs, and opportunities now and what are those in the future? Those problems, needs, and opportunities is going to help guide their objectives and project formulation,” she said. “For future conditions, they have to consider loss of different pieces, regulatory requirements, population, water demands, land use, infrastructure, climate, and then how all those things change: facilities, level of development, standards, regulations, decisions, permits, operation criteria, operating agreements, and other policies that are applicable to their project. This is not an easy list. Then once they define their future conditions, they have to put their project in it as well.”

There’s a lot of analysis that needs to be done just to define the baseline, Ms. Marr noted. “You have to look at your hydrologic and hydraulic system, as well as Delta hydraulic and hydrodrynamics because the statute requires that we have measurable improvements to the ecosystem in the Delta, so you’ve got take your analysis down to the Delta. There is climate change and sea level rise analysis to see how the hydrologic system changes under uncertain future conditions, as well as water quality, temperature, species habitat, energy analysis, and resource specific analysis to add on top of these already challenging and time consuming analyses, just to develop baseline conditions.”

“Every model you develop, you have to run at least twice, and that’s if things are perfect and if you’ve only got a couple of things to look at,” she said. “But our regulations ask folks to run models more than twice, because we’re looking at different baselines, we’re looking at different futures, we’ve got to look at it without project condition and with project condition, and those changes we’re looking at in its most simple form are the with or without project conditions. That’s how we get to our physical changes that we’re going to monetize and do our funding decision on.”

A CalSIM primer

Ms. Marr then gave some details on the CalSIM model. “Models have to be appropriate to the project type, size, area of influence, available data, and the decision to be made,” she said. “CalSIM comes into play when there are large scale projects that may impact the operations of the State Water Project and the Central Valley Project. And if that is the case, applicants need to expand their study area to include the watersheds of those large scale water projects, so CalSim is the model that provides the representation and is considered the best available planning model for CVP and SWP system operations.”

CalSIM is a model developed by the Department of Water Resources and the Bureau of Reclamation. It includes the hydrologic regions for the Sacramento River, the San Joaquin River, the Delta, the Trinity, and all the delivery locations and all the contractor locations for the CVP and the SWP. She presented a schematic for CalSIM, noting that the blue line in the middle is the Sacramento River; it illustrates all the connections and all of the various movement and delivery of water within this system. “It’s a complex model and it definitely has its utility, but there are some limitations,” she noted.

The inputs to CalSIM include hydrology, facility, regulatory requirements, and operations criteria; the outputs are river flows, diversions, reservoir storage and releases, Delta flows and exports, Delta inflows and outflows, deliveries to project and non-project users, and controls on project operations.

Ms. Marr reminded that CalSIM is only part of the equation and will only be used by some applicants. “Some of the take homes are that CalSIM II results feed into other models, it does not provide results specific to the public benefit categories, you can get Delta outflow from it which a lot of folks will use for ecosystem improvement, but it doesn’t dive into the other categories or potential benefits or public benefits. So while CalSIM is part of the equation, but it doesn’t give you or the applicant what you need to make decisions on public benefits.”

She noted that CalSIM also simulates operations on a monthly time-step which is appropriate for its application, but not for a lot of the public benefit calculations and analysis such as flood. “Flood needs a more specific daily time-step because if you did a flood analysis based on a monthly time-step, you’d probably miss that flood,” she said.

Ms. Marr presented a slide showing how flood analysis might be done to provide context for how CalSIM fits into an analysis and how running even one operations model won’t get the public benefit information that is needed. “This schematic just shows the interrelated technical analysis for computing expected annual damage and expected potential fatalities during a flood event,” she said. “It’s pretty involved; this is the analysis you might see done for the Central Valley flood protection plan or any of the basin-wide feasibility studies.”

Ms. Marr presented a slide showing how flood analysis might be done to provide context for how CalSIM fits into an analysis and how running even one operations model won’t get the public benefit information that is needed. “This schematic just shows the interrelated technical analysis for computing expected annual damage and expected potential fatalities during a flood event,” she said. “It’s pretty involved; this is the analysis you might see done for the Central Valley flood protection plan or any of the basin-wide feasibility studies.”

“It takes you through defining flood hydrology, the reservoir analysis, and CalSIM provides some information on the reservoir analysis, but the time-step isn’t good enough for a detailed flood control analysis,” she said. “You have to run additional reservoir analysis and doing that hydrology, reservoir analysis, and riverine channel gives you that definition of the flood hazard. There’s a lot of steps in just defining a hazard.”

“Then you have to look at the performance of levees, generally called the fragility curve of how a levee performs under different elevations of water,” she said. “Then you want to take the results of all this analysis into an economic damage model, because each of one of these steps has a different model that you would run to do the necessary calculation and get the necessary information that you need to move onto the next step. So it’s that description of flood hazard, levee performance, vulnerability, and exposure because it’s that economic damage analysis that really takes into account the exposure and what’s exposed to the flood hazard to get you to economics.”

“Then you have to look at the performance of levees, generally called the fragility curve of how a levee performs under different elevations of water,” she said. “Then you want to take the results of all this analysis into an economic damage model, because each of one of these steps has a different model that you would run to do the necessary calculation and get the necessary information that you need to move onto the next step. So it’s that description of flood hazard, levee performance, vulnerability, and exposure because it’s that economic damage analysis that really takes into account the exposure and what’s exposed to the flood hazard to get you to economics.”

This is just one public benefit category, and these are the inter-related analyses that need to be done, she said. “So getting from an unregulated flow frequency curve to a flood damage frequency curve takes a lot of different steps and a lot of different models to get there. There’s a lot of complicated stuff going on, but when it comes down to decision making, we’re mostly looking at that final result, the flood damage frequency curve, but it’s important for decision makers to understand the assumptions that went into the model, and how those assumptions might change the final results.”

In conclusion …

“The models that we have available right now are very good and they are very informative, but they are not crystal balls,” she said. “Models are best suited for comparative analysis, but that makes your job even harder, because the results that you get are good for comparing one project to another, or projects against themselves in their various scenarios, but your task is making an absolute funding decision, based on the results of these models. So over the next couple months, we’ll be working on proposals for the evaluation regulations and try to set up a system that allows you to use these tools to make these informed absolute decisions.”

There are a variety of types of models, so the staff has proposed a system to recognize this variety and complexity, and that the applicant has the flexibility to choose the best tools for their project, she said. “We’re not saying that there’s one model to rule them all,” she said. “It requires significant documentation and justification to be provided by the applicant. They have to tell us how they used the model, what the results mean, how those results might change under different conditions, and so that requires a large enough review team to make sure that we’ve got people that can review all this different types of information. And we’ve got a deep bench at DWR to support this technical review.”

“Because of the variety and complexity of information that’s coming in, we’ll take the application and develop dashboard information so the commission will see consistent information across all projects that’s boiled down to the specific information you need to make those four findings and your two decisions.”

For more information …

- For the agenda and meeting materials for the February meeting of the California Water Commission, click here. This was agenda item 10.

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!