The Delta Narratives project continues with a look at the history of boating, trains, trucks, and mechanical innovation in the Delta

In 2014, the Delta Protection Commission funded the Delta Narratives project, teaming up with scholars, regional museums and others to tell the story of the Delta and to communicate its importance to California’s and the nation’s history.

“The imprint of every stage in California’s history is visible along its shores: the fur-bearing animals that attracted trappers and traders, the ports of call for those rushing for gold, the transportation and reclamation technology that made farming successful, the factories built near its coal reserves to construct ships and process the area’s agricultural bounty, and the communities created by diverse immigrant groups whose labor fueled the Delta’s cyclical economic success,” notes the Delta Narratives report.

In this second installment of the Delta Narratives project, Dr. Reuben Smith and Dr. William Swagerty, both historians from the University of the Pacific’s Department of History, presented their essay, Stitching a River Culture: Trade, Transportation and Communication in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

Dr. William Swagerty began by noting the themes for their portion of the project were defining the Delta, the population before and after the Gold Rush, the Delta as an obstacle between coast and interior, the emergence of Sacramento and Stockton as supply points for the mines and the link with the Bay Area, and then Stockton and Sacramento as manufacturing towns.

Dr. Reuben Smith began the presentation, focusing on the Delta as a transportation corridor, a catalyst for mechanical and technological innovation, producer of ag products, and a destination for recreation and tourism.

For the geographic starting point, they began with the official Delta Protection Commission map, but also extended a bit further east to include Lodi and environs due to the transportation corridors; but all other boundaries they agreed with, Dr. Swagerty said.

He presented the proposed National Heritage Area map, noting that the status of it is really unknown at this point. “It hasn’t gone through committee yet,” he said. “It’ll be the third time it’s been introduced. It would be through the National Park Service as California’s first National Heritage Area.”

He presented the proposed National Heritage Area map, noting that the status of it is really unknown at this point. “It hasn’t gone through committee yet,” he said. “It’ll be the third time it’s been introduced. It would be through the National Park Service as California’s first National Heritage Area.”

It’s important to note the native tribes of the Delta and give them credit for successfully adapting to the Delta’s ecosystems, he said. “Their numbers weren’t huge, but they certainly were present well into the Gold Rush period,” he said. “Unfortunately for them and for California generally, they pretty much were wiped out in the Delta region and forced to amalgamate with other groups or suffer near enslavement or servitude during the 1850s.”

It’s important to note the native tribes of the Delta and give them credit for successfully adapting to the Delta’s ecosystems, he said. “Their numbers weren’t huge, but they certainly were present well into the Gold Rush period,” he said. “Unfortunately for them and for California generally, they pretty much were wiped out in the Delta region and forced to amalgamate with other groups or suffer near enslavement or servitude during the 1850s.”

He presented a painting introduced to them as part of the Delta Protection Commission Project. “Laura Cunningham has done this conjectural sketch which is based in part upon the actual sketch in 1850 of the native village near Hock Farm, owned by John Sutter,” he said. “You can see the conical above-ground housing that’s actually semi underground as well and then the infamous tule reed boat, the dominant vegetative cover type in the Delta being the tule.”

He presented a painting introduced to them as part of the Delta Protection Commission Project. “Laura Cunningham has done this conjectural sketch which is based in part upon the actual sketch in 1850 of the native village near Hock Farm, owned by John Sutter,” he said. “You can see the conical above-ground housing that’s actually semi underground as well and then the infamous tule reed boat, the dominant vegetative cover type in the Delta being the tule.”

“In the mid-1800s, the Spaniards were interested in reconnoitering and perhaps even building a mission in the Delta country, but it didn’t happen,” he said. “The reason it didn’t happen was it was just too wet. It was always deemed an obstacle, both for boats and for horses who wanted to walk overland into the interior of California, and it was perceived as dangerous by the Spaniards, so they gave up on building in the Delta. The last mission was built in Sonoma. That was to be originally a mission in the Delta, and by 1823, in the Mexican period, it was completed far to the north in Sonoma.”

“In the mid-1800s, the Spaniards were interested in reconnoitering and perhaps even building a mission in the Delta country, but it didn’t happen,” he said. “The reason it didn’t happen was it was just too wet. It was always deemed an obstacle, both for boats and for horses who wanted to walk overland into the interior of California, and it was perceived as dangerous by the Spaniards, so they gave up on building in the Delta. The last mission was built in Sonoma. That was to be originally a mission in the Delta, and by 1823, in the Mexican period, it was completed far to the north in Sonoma.”

“There wasn’t much Native California population left by the 1830s anyway,” he said. “By the time the Spaniards had built their last mission, disease had already run its toll through much of California. In 1769, the estimated population was 310,000; as wave after wave of European crowd diseases, especially smallpox, mumps, and measles, as well as malaria in 1833 – a 50% mortality rate was what Sherburne Cook predicted in his calculations, and that has stood since 1976 as pretty much the figure that most demographers work with. By 1855, well, by the time of the Gold Rush, only 100,000. By 1855, 50,000, and by 1880, only 20,000 natives left in all of California.”

As for the non-native people, the world rushed in, he said. “In 1849, 100,000 folks alone come into California, most of them male. The sex ratio very imbalanced, 10 to 1, men to women. In 1850, 150,000, still imbalanced, 6 to 1 men to women. In 1852 census, the state census there was a little over a quarter million people. Then, by 1860, 380,000; 1870, there were 560,000, and by 1880, near 865,000, so California really came into statehood as unique in American history in terms of a population explosion.”

As for the non-native people, the world rushed in, he said. “In 1849, 100,000 folks alone come into California, most of them male. The sex ratio very imbalanced, 10 to 1, men to women. In 1850, 150,000, still imbalanced, 6 to 1 men to women. In 1852 census, the state census there was a little over a quarter million people. Then, by 1860, 380,000; 1870, there were 560,000, and by 1880, near 865,000, so California really came into statehood as unique in American history in terms of a population explosion.”

The Delta has not been studied much academically, but much credit is due to a dissertation done by John Thompson at Stanford in 1957. “It has not been published, but it’s been used over and over again. The maps are rather crude. It was typed physically on a manual typewriter, so it’s never been digitized, as far as I know, but we did use it, and we have some of the maps from that. Some of his data is also very good, especially on reclamation and crops.”

There were numerous ways to acquire land in the Delta in the mid-1800s. “First of all, one could get a Mexican land grant, and quite a few people did. You could purchase from the Mexican Californians who had been here for three or four generations in many cases; they had the land grants and they were willing to break them up and sell off parcels of it,” he said. “You could squat or preempt on vacant lands, and a lot of people did that. We call them ‘rimlanders’ and back trailers into the Delta, two different kinds that have been studied as people who were Gold Rush bound, Sierra bound, and then came back towards San Francisco, settling in the Delta on the way back to the coast.”

There were numerous ways to acquire land in the Delta in the mid-1800s. “First of all, one could get a Mexican land grant, and quite a few people did. You could purchase from the Mexican Californians who had been here for three or four generations in many cases; they had the land grants and they were willing to break them up and sell off parcels of it,” he said. “You could squat or preempt on vacant lands, and a lot of people did that. We call them ‘rimlanders’ and back trailers into the Delta, two different kinds that have been studied as people who were Gold Rush bound, Sierra bound, and then came back towards San Francisco, settling in the Delta on the way back to the coast.”

“You could acquire federal or state land by several important land legislative acts, the most important being the 1850 Swamp and Overflow Lands Act, which, in many cases, every major farmer around Stockton accessed this to get at least 40 and in some cases 80 or up to 160 acres,” he said. “The 1858 California Lands Act extended the Swamp Lands Act over state lands, and that helped, too. Very easy to acquire with very little money. And the Homestead Act of 1862 which is the best known of these three.”

He then presented a map showing some of the land grants acquired by 1850 on the periphery and within the Delta, noting the well-known lands of John Sutter and Charles Weber, as well as John Marsh down by Mount Diablo, and the lesser known Robert Semple and William Wolfskill lands, and then the one to the south as well, the Valentin Higuera & Rafael Felix lands. By 1906, over 2 million acres had been claimed under the Swamp and Overflow Lands Act.

He then presented a map showing some of the land grants acquired by 1850 on the periphery and within the Delta, noting the well-known lands of John Sutter and Charles Weber, as well as John Marsh down by Mount Diablo, and the lesser known Robert Semple and William Wolfskill lands, and then the one to the south as well, the Valentin Higuera & Rafael Felix lands. By 1906, over 2 million acres had been claimed under the Swamp and Overflow Lands Act.

“The development of Sacramento and Stockton is a pretty phenomenal story in itself in terms of rapidity of urbanization, not it was without many problems, the largest of which was flooding,” he said. “These eyewitness sketches are really telling of how Sacramento developed so quickly and how the technology and the landscape changed so quickly. In a 6-year period, from trees and sailboats almost dominating the waterfront there to almost no trees, some brick buildings, and steamboats by 1855.”

“The development of Sacramento and Stockton is a pretty phenomenal story in itself in terms of rapidity of urbanization, not it was without many problems, the largest of which was flooding,” he said. “These eyewitness sketches are really telling of how Sacramento developed so quickly and how the technology and the landscape changed so quickly. In a 6-year period, from trees and sailboats almost dominating the waterfront there to almost no trees, some brick buildings, and steamboats by 1855.”

He then presented a depiction of the great inundation of 1850, noting that the worst flood in the state’s history would come in 1862; it would require the capital be moved to San Francisco because of the flood and then back here, he said.

He then presented a depiction of the great inundation of 1850, noting that the worst flood in the state’s history would come in 1862; it would require the capital be moved to San Francisco because of the flood and then back here, he said.

Dr. Swagerty then presented a lithograph of Stockton in 1850, showing Captain Weber’s store as well as all these flour sacks as Stockton already a grain and hay center for the Gold Rush and the southern mines in particular.

Dr. Swagerty then presented a lithograph of Stockton in 1850, showing Captain Weber’s store as well as all these flour sacks as Stockton already a grain and hay center for the Gold Rush and the southern mines in particular.

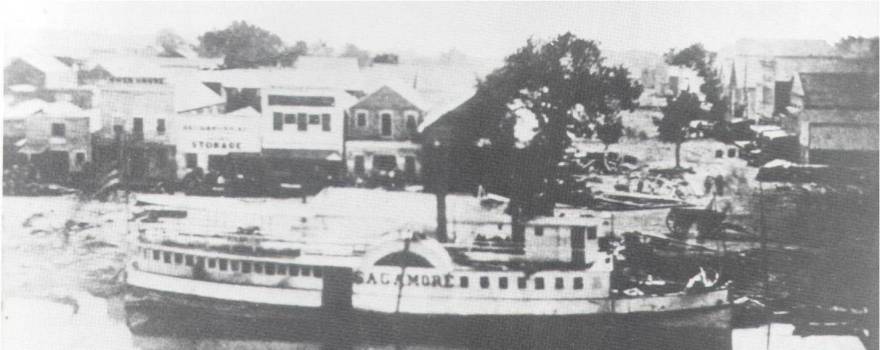

Stockton became a major steamboat town, as did Sacramento. “They paralleled, really,” he said. “We argue in our essay that it’s a triangular relationship: The Bay Area, Sacramento, and Stockton, even though the traffic between Stockton and Sacramento was not a parallel one – that is, it wasn’t equal to the commerce between San Francisco and Sacramento, and San Francisco and Stockton, but it is a triangular relationship with the wagon roads and later the railroads providing that link.”

Stockton became a major steamboat town, as did Sacramento. “They paralleled, really,” he said. “We argue in our essay that it’s a triangular relationship: The Bay Area, Sacramento, and Stockton, even though the traffic between Stockton and Sacramento was not a parallel one – that is, it wasn’t equal to the commerce between San Francisco and Sacramento, and San Francisco and Stockton, but it is a triangular relationship with the wagon roads and later the railroads providing that link.”

Stockton supplied the mines using freight wagons. “Its early manufacturing really centered on wheels, carriages, and wagons,” he said. “This is one of the earliest carriages factories in 1852. By 1865, the Stockton Wheel Works was manufacturing all kinds of wagons and tankers, etc., and this was one of their largest wheeled trammels for logging by 1880.”

Stockton supplied the mines using freight wagons. “Its early manufacturing really centered on wheels, carriages, and wagons,” he said. “This is one of the earliest carriages factories in 1852. By 1865, the Stockton Wheel Works was manufacturing all kinds of wagons and tankers, etc., and this was one of their largest wheeled trammels for logging by 1880.”

Stockton was a grain and flour shipping port, he said, presenting a picture of the port with Sperry Mills, which would later become General Mills, in the background.

Stockton was a grain and flour shipping port, he said, presenting a picture of the port with Sperry Mills, which would later become General Mills, in the background.

Ethnic communities are an important part of Delta history. Dr. Swagerty noted that Jennifer Helzer, who covered that portion for the Delta Narratives Project, would speak in more depth at her presentation, but he would just briefly mention them now: the Chinese, the Portuguese, the Italians, the Japanese, Filipinos, and then Hispanics.

Chinatowns on the Delta were an attractive draw for tourism and important historically, he noted. “This is very typical of the earliest China towns; they were stilted because Chinese couldn’t own land, they could only lease it from non-Chinese, so they actually lived on house boats more than they lived in even these apartments or houses that were built out on piers, in the earliest days. This was the most practical, safest, and cheapest way to live while building the levees of the Delta and working on the railroad as well.”

Chinatowns on the Delta were an attractive draw for tourism and important historically, he noted. “This is very typical of the earliest China towns; they were stilted because Chinese couldn’t own land, they could only lease it from non-Chinese, so they actually lived on house boats more than they lived in even these apartments or houses that were built out on piers, in the earliest days. This was the most practical, safest, and cheapest way to live while building the levees of the Delta and working on the railroad as well.”

The Portuguese came; they settled west of the river as well as in Sacramento in the pocket – Garcia Bend, he said. “The interesting thing to us about this is the ribboned or long-lots pattern that developed in the pocket, giving all of the Portuguese who settled in this area near-equal access to the river,” he said. He noted that it’s been gridded a bit differently in modern times, but the Lewis Ranch in 1946 still reflected the pattern.

The Portuguese came; they settled west of the river as well as in Sacramento in the pocket – Garcia Bend, he said. “The interesting thing to us about this is the ribboned or long-lots pattern that developed in the pocket, giving all of the Portuguese who settled in this area near-equal access to the river,” he said. He noted that it’s been gridded a bit differently in modern times, but the Lewis Ranch in 1946 still reflected the pattern.

The Italians settled in Martinez as well as Collinsville. They worked as fisherman and as fruit farmers, he said.

The Italians settled in Martinez as well as Collinsville. They worked as fisherman and as fruit farmers, he said.

The Japanese were important truck farmers and were early on important in the asparagus industry especially. “Any of the green crops that we think of on the Delta, the Japanese became involved with, and some of them became major owners. There was George Shima, the Potato King of the Stockton area, but there have been many, many others.”

The Japanese were important truck farmers and were early on important in the asparagus industry especially. “Any of the green crops that we think of on the Delta, the Japanese became involved with, and some of them became major owners. There was George Shima, the Potato King of the Stockton area, but there have been many, many others.”

Filipinos lived mainly in Stockton and worked the Delta by day, he said. “They became the great grass cutters with these very specialized knives that we found at the Rio Vista Museum.”

Filipinos lived mainly in Stockton and worked the Delta by day, he said. “They became the great grass cutters with these very specialized knives that we found at the Rio Vista Museum.”

In terms of Mexicans, there were many Mexicanos or Californios who stayed on the Delta or it’s periphery after American takeover and statehood in 1850, but most blended into the Anglo-controlled ranches, Dr. Swagerty said. “It really wasn’t until after World War I that we see a large influx of Mexican immigrants coming in to participate as migrant workers in the first of several bracero programs,” he said. “The bracero program from 1924 to 1930 brought 58,000 Mexicans on average per year were brought in; it’s estimated 4.5 million actually participated in the more well-known bracero program of World War II and beyond.”

In terms of Mexicans, there were many Mexicanos or Californios who stayed on the Delta or it’s periphery after American takeover and statehood in 1850, but most blended into the Anglo-controlled ranches, Dr. Swagerty said. “It really wasn’t until after World War I that we see a large influx of Mexican immigrants coming in to participate as migrant workers in the first of several bracero programs,” he said. “The bracero program from 1924 to 1930 brought 58,000 Mexicans on average per year were brought in; it’s estimated 4.5 million actually participated in the more well-known bracero program of World War II and beyond.”

Dr. Rueben Smith then took the floor to discuss transportation technology. “The important point to keep in mind is that there was a very close interrelationship of the development of technology and the development of the kinds of crops that were grown on the Delta,” he said, presenting a picture of sidewheeler steamboats. “A famous development here was that in 1861, the sidewheel steamer set a record from Sacramento to San Francisco in 5 hours 19 minutes, a record that still stands.”

Dr. Rueben Smith then took the floor to discuss transportation technology. “The important point to keep in mind is that there was a very close interrelationship of the development of technology and the development of the kinds of crops that were grown on the Delta,” he said, presenting a picture of sidewheeler steamboats. “A famous development here was that in 1861, the sidewheel steamer set a record from Sacramento to San Francisco in 5 hours 19 minutes, a record that still stands.”

“Sidewheel steamboats tend to take a little more draft, and so eventually toward the end of 19th century and into the 20th century, sternwheelers became the most important steamboats on the Sacramento River and the Delta in general,” he said.

“Sidewheel steamboats tend to take a little more draft, and so eventually toward the end of 19th century and into the 20th century, sternwheelers became the most important steamboats on the Sacramento River and the Delta in general,” he said.

By the early part of the 20th century, there had been enough development in agriculture to attract railroad building. The Sacramento Southern Railroad, a subsidiary of the Southern Pacific Railroad, started construction in 1906, from Sacramento down to Freeport and eventually through Walnut Grove to Isleton, Dr. Reuben said.

By the early part of the 20th century, there had been enough development in agriculture to attract railroad building. The Sacramento Southern Railroad, a subsidiary of the Southern Pacific Railroad, started construction in 1906, from Sacramento down to Freeport and eventually through Walnut Grove to Isleton, Dr. Reuben said.

“The dream of every railroad economist is that the railroad will be used year round, and so here, the Sacramento Southern Railroad is very proud to point out that from Walnut Grove, you can ship celery from November to February, asparagus from February to May, fruit from May through September, and seeds from September through November.”

“The dream of every railroad economist is that the railroad will be used year round, and so here, the Sacramento Southern Railroad is very proud to point out that from Walnut Grove, you can ship celery from November to February, asparagus from February to May, fruit from May through September, and seeds from September through November.”

On the west side of the Delta, the Sacramento Northern Railway was an electric railway which eventually ran from Oakland through Sacramento to Chico. It was 183 miles of electrified railway built down the west side of the Delta. He noted that they built a small branch line known as the Holland Branch which terminated in Oxford; there was a small branch to serve Clarksburg and the sugar beet factory there; they never did build to Rio Vista, which was their aim, said Dr. Smith.

On the west side of the Delta, the Sacramento Northern Railway was an electric railway which eventually ran from Oakland through Sacramento to Chico. It was 183 miles of electrified railway built down the west side of the Delta. He noted that they built a small branch line known as the Holland Branch which terminated in Oxford; there was a small branch to serve Clarksburg and the sugar beet factory there; they never did build to Rio Vista, which was their aim, said Dr. Smith.

The Western Pacific Railroad was the last railroad of the transcontinental railroads to be built. “Its line, which now is part of the Pacific line, runs along just east of Interstate 5 between Stockton and Sacramento,” he said. “It was built to Salt Lake City and eventually eastward, but it had junctions into the Delta, to termini along Highway 12 from just around Thornton.“

The Western Pacific Railroad was the last railroad of the transcontinental railroads to be built. “Its line, which now is part of the Pacific line, runs along just east of Interstate 5 between Stockton and Sacramento,” he said. “It was built to Salt Lake City and eventually eastward, but it had junctions into the Delta, to termini along Highway 12 from just around Thornton.“

“The important technological development was the internal combustion engine,” he said. “The Caterpillar tractor and the Transom Truck Company are both Stockton-based industries, and the tractor could be used not just for plowing but actually for towing wagon trains.”

“The important technological development was the internal combustion engine,” he said. “The Caterpillar tractor and the Transom Truck Company are both Stockton-based industries, and the tractor could be used not just for plowing but actually for towing wagon trains.”

There were inboard motors as well as the development of the outboard motor which made available the possibility of sport fishing and transportation of small boats, Dr. Smith noted.

There were inboard motors as well as the development of the outboard motor which made available the possibility of sport fishing and transportation of small boats, Dr. Smith noted.

“There’s a story that Ole Evinrude invented the outboard motor in order to be able to cross the lake to get ice cream for his fiancée so that he wouldn’t have to row,” Dr. Smith said. “But roads were a problem because the Delta soil is a very porous and very damp soil, and it raised all kinds of problems for any kind of transportation.”

Dr. Smith noted on the map the extent to the east that the wetlands extended, depicted with crosshatching on the map. Delta soils were porous and spongy and damp, he said.

Dr. Smith noted on the map the extent to the east that the wetlands extended, depicted with crosshatching on the map. Delta soils were porous and spongy and damp, he said.

After the beginning of highway construction, there were three main routes through the Delta: Highway 12, the east-west route from west of Suisun, through Rio Vista, past Lodi and into the Gold Country; Highway 160 coming down River Road to Antioch, and then Highway 4 from west of Martinez, through Antioch, and across the Delta, through Holt and into Stockton, and again on toward the Mother Lode.

After the beginning of highway construction, there were three main routes through the Delta: Highway 12, the east-west route from west of Suisun, through Rio Vista, past Lodi and into the Gold Country; Highway 160 coming down River Road to Antioch, and then Highway 4 from west of Martinez, through Antioch, and across the Delta, through Holt and into Stockton, and again on toward the Mother Lode.

The highways needed bridges to be able to cross, and since ferries had preceded the bridges, but the bridges had to be movable, so there were pivot bridges and the bascule bridges such as at Paintersville and Walnut Grove, he said.

The highways needed bridges to be able to cross, and since ferries had preceded the bridges, but the bridges had to be movable, so there were pivot bridges and the bascule bridges such as at Paintersville and Walnut Grove, he said.

With highway transportation running east to west through Rio Vista on Highway 12, or north to south through Rio vista on highway 160, Rio Vista became a hub for bus transportation. “The bus ran from the Sacramento northern junction or the Rio Vista junction as it’s called now, out to Isleton and actually into San Francisco as well,” he said.

With highway transportation running east to west through Rio Vista on Highway 12, or north to south through Rio vista on highway 160, Rio Vista became a hub for bus transportation. “The bus ran from the Sacramento northern junction or the Rio Vista junction as it’s called now, out to Isleton and actually into San Francisco as well,” he said.

Other mechanical innovations pushed Delta agriculture forward. He noted the horseshoe with the greater shoe around it which was brought in by the Chinese, and the Fresno scraper, which was used for leveling.

Other mechanical innovations pushed Delta agriculture forward. He noted the horseshoe with the greater shoe around it which was brought in by the Chinese, and the Fresno scraper, which was used for leveling.

Another important development was the application of steam to land transportation. “Notice the width of the wheels on the steam tractor to the left, but on the steam tractor to the right, you have three wheels on each side, each 6 feet wide, in order that they not sink into the soil,” he said. Steam tractors were used to haul dredges across the land from one waterway to another, and applied to pumps to move water around, he noted.

Another important development was the application of steam to land transportation. “Notice the width of the wheels on the steam tractor to the left, but on the steam tractor to the right, you have three wheels on each side, each 6 feet wide, in order that they not sink into the soil,” he said. Steam tractors were used to haul dredges across the land from one waterway to another, and applied to pumps to move water around, he noted.

Delta soil, being porous and being built by hand labor, was not a very practical levee at all, because it was too porous and the water went in and out, he said. “So the attempt was to be able to move more dirt faster than could be done by hand but also to be able to use the bottom soil from the channel, which was much thicker and could be compacted more easily, so steam shovels were tried, but the booms are really rather short, and there isn’t much of a reach.”

Delta soil, being porous and being built by hand labor, was not a very practical levee at all, because it was too porous and the water went in and out, he said. “So the attempt was to be able to move more dirt faster than could be done by hand but also to be able to use the bottom soil from the channel, which was much thicker and could be compacted more easily, so steam shovels were tried, but the booms are really rather short, and there isn’t much of a reach.”

So the clamshell steam dredge was developed; it could hold up to 6 yards with one bite from the bottom land soils, where were very solid and much thicker than the peat soils, he said. The clamshell dredge also had a long boom that could reach across the levee.

So the clamshell steam dredge was developed; it could hold up to 6 yards with one bite from the bottom land soils, where were very solid and much thicker than the peat soils, he said. The clamshell dredge also had a long boom that could reach across the levee.

With electricity, it became much easier to operate electric pumps than it was steam pumps, and so electricity made a big difference in pumping water and not just in lighting houses, he said.

With electricity, it became much easier to operate electric pumps than it was steam pumps, and so electricity made a big difference in pumping water and not just in lighting houses, he said.

The Holt Brothers developed the Caterpillar tractor in Stockton, Dr. Smith said. “There’s a story told that Holt was showing off one of these new inventions to somebody and asked, “What do you think about it?” and this person said, “Well, it looks like a caterpillar to me,” and Holt said, “That’s it! That’s what we’ll call it.””

The Holt Brothers developed the Caterpillar tractor in Stockton, Dr. Smith said. “There’s a story told that Holt was showing off one of these new inventions to somebody and asked, “What do you think about it?” and this person said, “Well, it looks like a caterpillar to me,” and Holt said, “That’s it! That’s what we’ll call it.””

Another person in the Stockton area not often remembered was Robert LeTourneau, and LeTourneau, who developed very large land moving and leveling equipment, first towed behind a Caterpillar tractor but then with its own power beginning in the 1930s and 40s that is land movement equipment which is now known all over the world.

Another very important innovation was the development of the refrigerated rail car. “Basically starting after 1906, produce could be shipped in iced refrigerator cars, and then in the 1930s in mechanical refrigerator cars, and that meant then that, instead of moving produce with horses and wagons and later on in small trucks to Delta water landings, they would be moved to these railroad terminals and loaded in refrigerated trucks.”

Another very important innovation was the development of the refrigerated rail car. “Basically starting after 1906, produce could be shipped in iced refrigerator cars, and then in the 1930s in mechanical refrigerator cars, and that meant then that, instead of moving produce with horses and wagons and later on in small trucks to Delta water landings, they would be moved to these railroad terminals and loaded in refrigerated trucks.”

“So trucks then became important, not only the early flatbed trucks but eventually the big refrigerator trucks, and that would mean then that there would be a change in what happened in Delta preservation,” he said.

The early crops were hay and grain which transitioned to field crops, particularly, by the late 19th and early 20th century. “Sugar beets became very important as candy, particularly chocolate candy production, outstripped the supply from cane sugar, so sugar beets were introduced, and sugar beet harvesting machinery had to be developed.”

The early crops were hay and grain which transitioned to field crops, particularly, by the late 19th and early 20th century. “Sugar beets became very important as candy, particularly chocolate candy production, outstripped the supply from cane sugar, so sugar beets were introduced, and sugar beet harvesting machinery had to be developed.”

Potatoes and beans were important crops, as well as asparagus. Other important field crops include celery and carrots.

Potatoes and beans were important crops, as well as asparagus. Other important field crops include celery and carrots.

The truck crops and orchards, particularly pear orchards, became important in the latter part of the 19th and in the earlier 20th century, when canning was developed.

The truck crops and orchards, particularly pear orchards, became important in the latter part of the 19th and in the earlier 20th century, when canning was developed.

“Canning was a way of preserving,” Dr. Smith explained. “It developed through the 19th century from very dangerous, poisonous canning in the earlier part of 19th century to dependable canning. Can lids became the width of the cylinder of the can, rather than having only a small opening with a stopper, so instead of having mushy foods put in the earlier cans, whole chunks, such as pear chunks or meat chunks, could go into the canning.”

Canneries were growing, and not just fruits and vegetables but salmon was canned as well. The total fruit pack increased from 2.8 million in 1900 to almost 29 million cases in 1940. “As refrigeration came to be more important and canning began being much more developed in the heavy population centers, the canning and canneries in the Delta moved out and the canneries in the Delta fell into disrepair.”

Canneries were growing, and not just fruits and vegetables but salmon was canned as well. The total fruit pack increased from 2.8 million in 1900 to almost 29 million cases in 1940. “As refrigeration came to be more important and canning began being much more developed in the heavy population centers, the canning and canneries in the Delta moved out and the canneries in the Delta fell into disrepair.”

With the advent of the outboard motor, but in general, the Delta became a center of recreation and tourism with its many marinas and its many restaurants.

With the advent of the outboard motor, but in general, the Delta became a center of recreation and tourism with its many marinas and its many restaurants.

For more information …

- Click here for the essay, Stitching a River Culture: Trade, Transportation and Communication in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

- Click here for much more information on the Delta Narratives project.

- Click here to view all Delta Narratives articles posted on the Notebook.

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily email service and you’ll never miss a post!

Sign up for daily emails and get all the Notebook’s aggregated and original water news content delivered to your email box by 9AM. Breaking news alerts, too. Sign me up!