The Delta Protection Commission’s Delta Narratives project seeks to tell the human story of the Delta

The Delta Protection Commission’s Delta Narratives project seeks to tell the human story of the Delta

“These days the Delta is most often considered a reservoir or a habitat,” begins the introduction to the Delta Narratives report. “Although it has at times been referred to as “the heart of California” because of its centrality and rich natural endowment, its history and culture have been neglected. The Delta is a place that few know for its human stories.”

The Delta Narratives project, commissioned by the Delta Protection Commission in 2014, seeks to correct that neglect. The project was a collaboration between scholars, museum professionals, and archivists to research ways in which the Delta experience relates to regional and national history. As part of the project, four essays were produced which were focused on the themes of transportation and communication, reclamation and restoration, the building of ethnic and economic communities, and the changing perspectives of writers and visual artists which were then presented in a series of brown bag seminars.

Dr. Philip Garone, an associate professor of history from Cal State University Stanislaus, begins this first of four parts with an overview of his essay, Managing the Garden: Agriculture, Reclamation, and Restoration in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, which explores land and water use in the region from before European contact in 1769 to the beginning of the twenty-first century.

“My colleagues on this project have written about the economic and cultural history of the Delta; the Delta’s trade, transportation, and communication infrastructure; and even the literature and visual arts of the Delta,” he said. “My role, as an environmental historian, has been to write the long-term environmental history of the Delta, and it’s that topic that I’m here to discuss with you today.”

“I’ll begin by introducing the Delta, including its geological origins and its use by Native Americans,” he said. “However, the emphasis of my talk and of the narrative I produced lies first on the physical and ecological transformation of the Delta during the late 19th and early 20th century for a tidal wetland partially protected by natural levees and rich in natural resources to a reclaimed, intensively cultivated, highly engineered agricultural landscape; and second, on more recent environmental conditions in the Delta, including water quality issues and the restoration of wetlands around the region’s margins.”

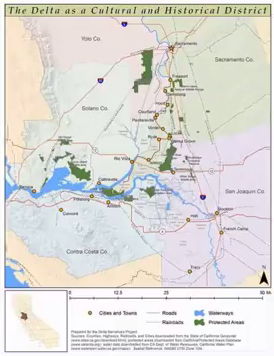

The Delta is bounded by the city of Sacramento to the north, Stockton to the east, and the smaller cities of Tracy and Antioch to the south and west respectively, yet the unique geography of the Delta isolates it from its surrounding regions. “Today, even as it serves as the lynchpin of the state’s hydraulic regime, through it drinking and irrigation water for about 25 million people is transported from north and southern California, the Delta remains rural, agricultural, and far less developed than its surroundings,” he said. “Ironically, despite its uniqueness and rich history, many Californians who reside outside of the Delta view the region in simple mechanistic terms, primarily as a water conveyance system.”

The Delta is bounded by the city of Sacramento to the north, Stockton to the east, and the smaller cities of Tracy and Antioch to the south and west respectively, yet the unique geography of the Delta isolates it from its surrounding regions. “Today, even as it serves as the lynchpin of the state’s hydraulic regime, through it drinking and irrigation water for about 25 million people is transported from north and southern California, the Delta remains rural, agricultural, and far less developed than its surroundings,” he said. “Ironically, despite its uniqueness and rich history, many Californians who reside outside of the Delta view the region in simple mechanistic terms, primarily as a water conveyance system.”

“As visitors enter the Delta, they are greeted with a roadside sign, such as this one, but what does it mean? What exactly is one entering? And what exactly is one leaving behind?” asked Dr. Garone.

“As visitors enter the Delta, they are greeted with a roadside sign, such as this one, but what does it mean? What exactly is one entering? And what exactly is one leaving behind?” asked Dr. Garone.

California’s Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta is one of the world’s great inland deltas, and it’s the largest estuary on the western coast of the Americas, he said. “Geologically speaking, the Delta is very young. The Delta as it exists now was created only about 6,000 to 7,000 years ago. By the end of the last ice age, rising sea levels had already pushed the Pacific Ocean 30 miles inland and filled in San Francisco Bay; that then impeded the flow of the lower Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers, backing the rivers out of their channels and creating a labyrinth of hundreds of miles of sluices, surrounding nearly 80 low-lying tracts and islands, the historical Delta.”

“The Delta’s dominant plant cover was the tule, which grows in dense stands and can reach well over 10 feet in height. Wetland vegetation partially composing over the thousands of years since the Delta has formed has created a layer of fertile peat soil that underlies most, but not all, of the region and accounts for it’s phenomenal agricultural productivity.”

“The Delta’s dominant plant cover was the tule, which grows in dense stands and can reach well over 10 feet in height. Wetland vegetation partially composing over the thousands of years since the Delta has formed has created a layer of fertile peat soil that underlies most, but not all, of the region and accounts for it’s phenomenal agricultural productivity.”

“Native Americans lived in the Delta, harvested its resources, and altered its environment for at least the past 6,000 years, continuing through the Spanish and Mexican periods of California’s history, and up until the Gold Rush and statehood, by which time Native American peoples had been decimated by the Central Valley malaria epidemic of the 1830s, and most of the surviving population had been displaced by the wave of American settlers.”

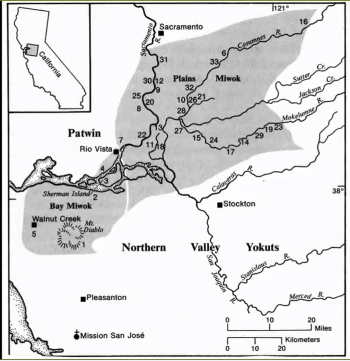

“Native American peoples inhabiting the Delta included the Plains Miwok, the Northern Valley Yokuts, the Bay Miwok, and the Patwin,” Dr. Garone said. “Native Americans harvested the Delta’s once abundant salmon, sturgeon, and shellfish; they captured waterfowl in numerous ingenious ways, and they hunted for game that included deer, pronghorn antelope, and elk. Indigenous people in the Delta region did not practice agriculture, but they harvested a variety of plant food sources, including acorns, grasses, and various wetland plants. And they modified the Delta in ways that supported their needs, such as burning wetland vegetation to prevent productive wetlands from filling in. They built villages, usually upon natural mounds or near the banks of major water courses. Their overall pre-contact population in the Delta has been estimated at 10,000 or greater.”

“Native American peoples inhabiting the Delta included the Plains Miwok, the Northern Valley Yokuts, the Bay Miwok, and the Patwin,” Dr. Garone said. “Native Americans harvested the Delta’s once abundant salmon, sturgeon, and shellfish; they captured waterfowl in numerous ingenious ways, and they hunted for game that included deer, pronghorn antelope, and elk. Indigenous people in the Delta region did not practice agriculture, but they harvested a variety of plant food sources, including acorns, grasses, and various wetland plants. And they modified the Delta in ways that supported their needs, such as burning wetland vegetation to prevent productive wetlands from filling in. They built villages, usually upon natural mounds or near the banks of major water courses. Their overall pre-contact population in the Delta has been estimated at 10,000 or greater.”

“The world of the indigenous people of California was altered by Spanish exploration and settlement beginning in 1769. The first documented discovery of the Delta occurred 3 years later, when a Spanish exploratory party traveling eastward from the Carquinez Strait reached Suisun Bay and recognized the junction of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers beyond. Journeys of discovery continued through the early 19th century, but over time, Spanish expeditions to the Delta became increasingly punitive in character, as the Spanish attempted to capture Native American fugitives from the Mission System. Time after time, however, Native Americans escaped capture by hiding in the nearly impenetrable tules. The Delta thus served as both a source of natural resources and as a place of refuge for Native Americans.”

“Meanwhile, American, British, and Russian fur trappers from Fort Ross in current day Sonoma County were penetrating the Delta region,” Dr. Garone said. “Two immediate consequences of the activities of the fur trappers were the destruction of populations of fur-bearing mammals, primarily beaver and fresh water otter, and the introduction of malaria which would have long-term consequences for the history of the Delta and the Central Valley as a whole.”

“Meanwhile, American, British, and Russian fur trappers from Fort Ross in current day Sonoma County were penetrating the Delta region,” Dr. Garone said. “Two immediate consequences of the activities of the fur trappers were the destruction of populations of fur-bearing mammals, primarily beaver and fresh water otter, and the introduction of malaria which would have long-term consequences for the history of the Delta and the Central Valley as a whole.”

“Malaria reached the central valley in late 1832, following in the wake of British fur trappers entering California from Oregon, where an outbreak had begun along the Columbia River in 1830,” Dr. Garone said. “The epidemic expanded from the head of the valley, first down the Sacramento River to the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, and then up the San Joaquin River. At least 20,000 Native Americans died on the river systems of the Central Valley, from Red Bluff in the north to Tulare Lake in the south, in 1833 alone. The Native American population in the affected parts of the valley may have been reduced by as much as 75% by 1846 in the wake of successive outbreaks.”

“Such profound depopulation reduced survivors’ resistance to the wave of white settlers who arrived in the valley during the Gold Rush and appropriated Native American territory, precipitating the final collapse of independent Delta cultures and mirroring statewide trends. In addition to the toll it took on Native Americans, the introduction of malaria into the Central Valley was important because it provided an additional incentive to drain and reclaim the wetlands of the Delta and lower Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, and thus, to begin the transformation of the Delta from a wetland region rich in plant and animal resources to an agricultural garden in the new Golden State.”

“The pre-reclamation Delta formed a heterogeneous landscape; not simply an estuarine marsh defined by impenetrable stands of tule. The tule lands, or freshwater tidelands, were indeed dominated by bulrush thickets but also by grasses, the latter of which supported livestock grazing, especially in the San Joaquin part of the Delta by the 1860s. Along the major rivers and especially the Sacramento River, high natural levees formed by depositions from over-bank flow supported a woodland of oak, sycamore, alder, walnut, and cottonwood, along with a dense understory of diverse species, including bunch grasses and willows and thickets of blackberry and wild rose. The land in between the rivers and streams that entered the Delta was characterized by extensive plains. North of the Calaveras River, the plains consisted of grassy woodland, of evergreen and deciduous oaks, but south of the river, the plains stretched nearly treeless to the Stanislaus River.”

“The pre-reclamation Delta formed a heterogeneous landscape; not simply an estuarine marsh defined by impenetrable stands of tule. The tule lands, or freshwater tidelands, were indeed dominated by bulrush thickets but also by grasses, the latter of which supported livestock grazing, especially in the San Joaquin part of the Delta by the 1860s. Along the major rivers and especially the Sacramento River, high natural levees formed by depositions from over-bank flow supported a woodland of oak, sycamore, alder, walnut, and cottonwood, along with a dense understory of diverse species, including bunch grasses and willows and thickets of blackberry and wild rose. The land in between the rivers and streams that entered the Delta was characterized by extensive plains. North of the Calaveras River, the plains consisted of grassy woodland, of evergreen and deciduous oaks, but south of the river, the plains stretched nearly treeless to the Stanislaus River.”

“One consequence of the difference in Delta topography was that while few people inhabited the flood-prone lands of the central Delta, by the 1870s, the lands adjacent to the Sacramento River downstream of the city of Sacramento were both populated and prosperous,” Dr. Garone said. “Truck farms and dairy operations were established in the vicinity of Freeport and west across the river in the Lisbon district. Orchards, fields, and gardens flourished along the river from north of Courtland to south of Walnut Grove. Fruit trees thrived in the well-drained soil adjacent to the river, and early orchards included stone fruits such as peach, nectarine, and plum, as well as apples and pears. In order for agricultural prosperity to expand beyond these narrow margins, the Delta would need to be reclaimed.”

“The reclamation of the Delta was first set in motion by the Federal Swamp and Overflowed Lands Act of 1850. To encourage reclamation of those parts of the public domain that were then considered wasteland, under this act, the Federal Government granted nearly 2.2 million acres of swampland to the state of California.”

“The origins of this act are interesting and are part of a larger national story. The prevailing 19th century view of wetlands, then generally referred to as swampland, was that they represented an obstacle to cultivation, settlement, and the fulfillment of America’s Manifest Destiny. Draining and reclaiming such lands, perfecting what was perceived as an imperfect nature, was a national imperative, and in 1849, Congress passed the first Swamp Land Act, in which it granted to the state of Louisiana ‘the whole of those swamp and overflowed lands which may be or are found to be unfit for cultivation.’ On September 28, 1850, Congress broadened the program via the Swamp and Overflowed Lands Act, which extended the federal land grant to twelve additional states, including California, all of which encompassed extensive wetlands, and the idea was that the states would sell the swampland to those who would drain it and convert it to agricultural use. Nearly 500,000 of the 2.2 million acres granted to California were located within the Delta.”

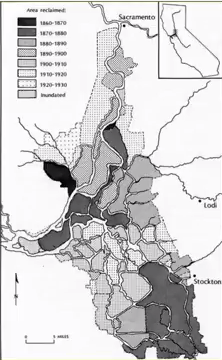

“Reclamation of the Delta islands began in earnest during the 1860s, and over the next half century, the Delta was almost entirely reclaimed. Overall, between 1860 and 1930, more than 440,000 Delta acres were reclaimed,” Dr. Garone said.

“Reclamation of the Delta islands began in earnest during the 1860s, and over the next half century, the Delta was almost entirely reclaimed. Overall, between 1860 and 1930, more than 440,000 Delta acres were reclaimed,” Dr. Garone said.

“So who built the earliest Delta levees, the first step in reclamation? As early as 1852, Californians had proposed the use of Chinese laborers for the reclamation of the tule lands. At that time, however, the Chinese were working claims in the gold mines until they were systematically driven out by white miners. In the 1860s, thousands of Chinese found employment on the transcontinental railroad, but after its completion in 1869, they were available to work on reclamation projects. Recruited from Chinatown boarding houses in Sacramento, Stockton, and San Francisco, for 3 decades Chinese laborers built the levees that transformed the Delta.”

“Some of the earliest reclamation works were constructed on Ryer, Grand, Andrus, Brannan, Tyler, and Staten Islands during the late 60s and early 1870s. A great deal of work was carried out also at this time on Sherman Island and Twitchell Island, but river floods and storm surges resulted in serious levee breaches that obliterated much of this early work, and the westernmost portion of Sherman Island was never able to be reclaimed. Today, it remains flooded as the lower Sherman Island Wildlife Area.”

“Some of the earliest reclamation works were constructed on Ryer, Grand, Andrus, Brannan, Tyler, and Staten Islands during the late 60s and early 1870s. A great deal of work was carried out also at this time on Sherman Island and Twitchell Island, but river floods and storm surges resulted in serious levee breaches that obliterated much of this early work, and the westernmost portion of Sherman Island was never able to be reclaimed. Today, it remains flooded as the lower Sherman Island Wildlife Area.”

“Levee breaches caused by floods were not the only problems associated with reclamation. In order to cultivate reclaimed land, it first needed to be cleared,” Dr. Garone said. “Burning was the accepted method of removing the tule vegetation of the peat lands, not only because it produced a fertile seed bed but also because it was believed to eliminate swampland vapors that were then believed to be the cause of malaria. Despite the often spectacular crop yields that it produced, the burning of peat accelerated the process of land subsidence. Once dried and exposed to oxygen, peat, of course, naturally decomposes and subsides. Burning further contributed to the subsidence of the land, placing greater pressure on the levees and increasing the likelihood of their collapse.” He noted that in present day, some Delta islands are subsided 20 feet or more.

“Much of the swamp and overflowed land ended up in the hands of corporations, such as George Roberts’ Tide Land Reclamation Company, and of other wealthy individuals who purchased and reclaimed entire islands or large parts of them. Roberts, who in the late 19th century was called the King of the Delta, purchased those lands with an eye toward quick profits that could then be invested in mining and in further land speculation. Paying between $1 and $4 an acre for Delta swampland and another $6 to $12 an acre to drain it and build levees, the Tide Land Reclamation Company then quickly sold the reclaimed land for between $20 and $100 an acre, reaping a huge windfall. George Roberts’ Tide Land Reclamation Company alone employed at least 3,000 Chinese men in 1876, for example, and by that year, Chinese laborers had reclaimed 30,000 to 40,000 acres of that company’s land. Trapped by poverty and bound by labor contracts, these men drained the tule lands despite suffering from malaria, dysentery, and the backbreaking nature of the work itself.”

“By the late 19th century, mechanical dredges had replaced manual labor for the construction of levees, but by that time, many Chinese had settled to farm, as laborers and as tenants, the land that they had reclaimed. Nowhere in California was the influence of the Chinese felt more than in the Delta, where they settled in the communities of Walnut Grove, Isleton, Courtland, and Rio Vista, and later founded the town of Locke.”

“By the late 19th century, mechanical dredges had replaced manual labor for the construction of levees, but by that time, many Chinese had settled to farm, as laborers and as tenants, the land that they had reclaimed. Nowhere in California was the influence of the Chinese felt more than in the Delta, where they settled in the communities of Walnut Grove, Isleton, Courtland, and Rio Vista, and later founded the town of Locke.”

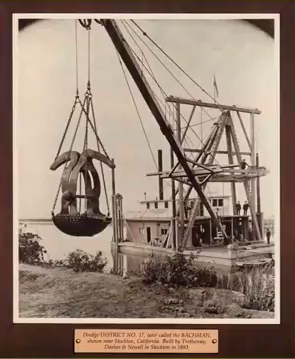

“The fragile peat levee systems, constructed primarily by hand in the Delta during the 1860s-1870s were largely destroyed by river floods and by storm surges, and they were replaced by new and stronger levees formed from material dredged from the channels by long-boom clamshell dredges, which evolved from early floating mechanical dredges that had been developed for harbor work in San Francisco,” Dr. Garone said. “As the name suggests, clamshell dredges were fitted with a single bucket composed of a pair of hinged shells that closed around the material to be emplaced. The clamshell bucket was suspended from a movable boom and supported by an A-frame.”

“Over time, the length of the boom and the capacity of the bucket increased substantially. Here we see a relatively early dredge named Ryer Island, which possessed a boom of 130 feet and a bucket with a capacity of 2 cubic yards; by the early 20th century, booms would extend to well over 200 feet. The most important advantage of the long boom was that a dredge so equipped can dig in a channel at a considerable distance beyond the outside of an extant levee, thus not excavating so close to the levee as to undermine it. It could also extract alluvial and mineral soils from the beds of the channels, which made for far more stable levees than peat soils taken from the interior of the islands.”

“Over time, the length of the boom and the capacity of the bucket increased substantially. Here we see a relatively early dredge named Ryer Island, which possessed a boom of 130 feet and a bucket with a capacity of 2 cubic yards; by the early 20th century, booms would extend to well over 200 feet. The most important advantage of the long boom was that a dredge so equipped can dig in a channel at a considerable distance beyond the outside of an extant levee, thus not excavating so close to the levee as to undermine it. It could also extract alluvial and mineral soils from the beds of the channels, which made for far more stable levees than peat soils taken from the interior of the islands.”

“Names given to many of the dredges are evocative of locales throughout the Delta and testified to their importance in reclaiming the region. During the 1880s and 1890s, clamshell dredges appointed with the names Staten Island, Mokelumne, Jersey Island, Andrus Island, Ryer Island, Calaveras, Merritt Island, Roberts Island, Grand Island, District 17, and Rough and Ready all entered service. Other dredges of various kinds were named more fancifully, as Samson, Goliath, Atlas, and Hercules – a reflection not only of their size, but also of the monumental task they were carrying out.”

“There were ecological consequences, however, to the successful reclamation and transformation of the Delta,” Dr. Garone noted. “Wetland vegetation in the Delta all but disappeared and the dense concentrations of wildlife that had thrived in and around the tules vanished with them. The Delta’s wetlands, which had once provided sustenance for Native Americans and habitat for millions of waterfowl, were converted into agricultural fields, orchards, and pastures.”

“Potatoes, beans, orchard crops, principally pears, asparagus, sugar beets, wheat, barley, corn, and alfalfa hay were each important components of the Delta’s agricultural economy for at least some portion of the major reclamation period from approximately 1860 to 1930. Potatoes, often grown with beans, were usually the first crop planted on newly reclaimed peat soils.”

“During the late 18th century, asparagus became the most profitable vegetable in the Delta, and acreage expanded rapidly. The development and proliferation of asparagus canneries in and around the Delta beginning in 1892 dramatically increased demand and accelerated the expansion of the crop. In that year, Robert Hickmott built the Delta’s first successful cannery on Bouldin Island. Railroads then made possible the expansion of the asparagus market, and in August 1900, the Hickmott Company shipped the first trainload of canned asparagus to an eastern market, sending at least twenty carloads to New York. Other canneries appeared in short order, and by the mid 1920s, canning companies were located in Isleton, Walnut Grove, Rio Vista, Ryde, Antioch, and Pittsburg, as well as Oakland and San Francisco.”

“During the late 18th century, asparagus became the most profitable vegetable in the Delta, and acreage expanded rapidly. The development and proliferation of asparagus canneries in and around the Delta beginning in 1892 dramatically increased demand and accelerated the expansion of the crop. In that year, Robert Hickmott built the Delta’s first successful cannery on Bouldin Island. Railroads then made possible the expansion of the asparagus market, and in August 1900, the Hickmott Company shipped the first trainload of canned asparagus to an eastern market, sending at least twenty carloads to New York. Other canneries appeared in short order, and by the mid 1920s, canning companies were located in Isleton, Walnut Grove, Rio Vista, Ryde, Antioch, and Pittsburg, as well as Oakland and San Francisco.”

“The canning process did not completely supersede the sale and marketing of fresh asparagus, though,” noted Dr. Garone. “Refrigerated railroad cars, then known as ‘reefers,’ became far more commonplace around the turn of the century and made it possible to ship fresh, rather than canned, asparagus—as well as other fresh Delta produce— throughout the country.”

“The development of physical infrastructure such as the canneries that helped promoted asparagus also led to increased production of other crops, including sugar beets. The first sugar beet refinery in the Delta was established in Isleton as early as 1876, though the crop did not become commercially important until the World War I era when sugar shortages encouraged greater production. Acreages increased dramatically in the 1920s, especially on the mineral soils along the Sacramento River and in the Yolo Basin. Much later, during the last decades of the 20th century, rising costs of production and increased competition from overseas and from other regions of the US contributed to the closure of California’s sugar refineries, and sugar beet production in the Delta plummeted.”

“The development of physical infrastructure such as the canneries that helped promoted asparagus also led to increased production of other crops, including sugar beets. The first sugar beet refinery in the Delta was established in Isleton as early as 1876, though the crop did not become commercially important until the World War I era when sugar shortages encouraged greater production. Acreages increased dramatically in the 1920s, especially on the mineral soils along the Sacramento River and in the Yolo Basin. Much later, during the last decades of the 20th century, rising costs of production and increased competition from overseas and from other regions of the US contributed to the closure of California’s sugar refineries, and sugar beet production in the Delta plummeted.”

“Interesting, however, a defunct refinery was repurposed. In 2000, renovations began to convert the refinery in Clarksburg into a multi-tasting-room venue and wine production facility. The venue, renamed the Old Sugar Mill opened to the public in 2005.”

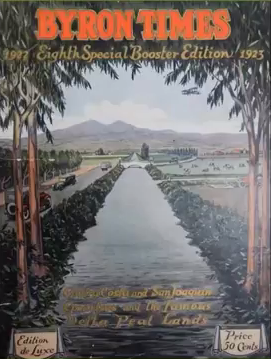

“Throughout the reclamation period and beyond, the Delta actively promoted itself as an agricultural mecca, an idyllic pastoral Eden,” said Dr. Garone. “For much of the first half of the 20th century, booster magazines, such as the Byron Times, touted the richness of the Delta soils, the latest agricultural breakthroughs, and the importance of the Delta for California’s economy. Over the decades, the ratio of crops grown in the delta changed, reflecting shifting market forces, and tomatoes, for example, became increasingly important for the cannery industry. They were raised for canning beginning early in the 20th century but became important for this purpose on an industrial scale after 1935 when Tillie Weisberg, in partnership with Italian canning executives, opened the first Delta tomato cannery in Stockton. This plant was the first of several that would be established over the next few decades to process the harvest of expanding tomato acreage in San Joaquin and Yolo counties. Despite changes in the relative importance of different crops, a process which continues to the present day, agriculture has, of course, remained the primary land use in the Delta.”

“Throughout the reclamation period and beyond, the Delta actively promoted itself as an agricultural mecca, an idyllic pastoral Eden,” said Dr. Garone. “For much of the first half of the 20th century, booster magazines, such as the Byron Times, touted the richness of the Delta soils, the latest agricultural breakthroughs, and the importance of the Delta for California’s economy. Over the decades, the ratio of crops grown in the delta changed, reflecting shifting market forces, and tomatoes, for example, became increasingly important for the cannery industry. They were raised for canning beginning early in the 20th century but became important for this purpose on an industrial scale after 1935 when Tillie Weisberg, in partnership with Italian canning executives, opened the first Delta tomato cannery in Stockton. This plant was the first of several that would be established over the next few decades to process the harvest of expanding tomato acreage in San Joaquin and Yolo counties. Despite changes in the relative importance of different crops, a process which continues to the present day, agriculture has, of course, remained the primary land use in the Delta.”

“The ways in which people made a living off the land through agriculture were not the only aspects of life in the Delta that evolved during the century or so from the Gold Rush to the completion of reclamation,” Dr. Garone said. “The Delta’s water resources, especially its Chinook salmon, were also exploited during this era on an industrial scale. Salmon are anadromous fish; after hatching in rivers, they spend much of their adult lives at sea, and then return to those same rivers in mass migrations (called runs) to spawn. The presence of four salmon runs—spring, fall, late fall, and winter—gave rise during the last third of the nineteenth century to a Delta thriving fishery and a canning industry before the fishery collapsed dramatically by 1900.”

“By the early 1850s, some five dozen boats were already fishing the Sacramento River for salmon from its confluence with the American River to its outlet into Suisun Bay. Much of the labor of harvesting the fish was carried out by Italian, Greek, Portuguese, and Spanish immigrants. Rio Vista emerged as the main landing station, and the salmon fishery brought significant wealth to the town through the 1880s.”

“In 1864, William Hume opened the first cannery on the Sacramento River, pictured here, on a scow moored on the west bank across from Sacramento. The cannery industry grew rapidly after the mid 1870s. Unlike the primarily southern European fishermen themselves, most of the cannery workers were Chinese laborers. Peak production occurred in 1882, when 19 canneries packed 200,000 cases – not cans – but cases of salmon.”

“In 1864, William Hume opened the first cannery on the Sacramento River, pictured here, on a scow moored on the west bank across from Sacramento. The cannery industry grew rapidly after the mid 1870s. Unlike the primarily southern European fishermen themselves, most of the cannery workers were Chinese laborers. Peak production occurred in 1882, when 19 canneries packed 200,000 cases – not cans – but cases of salmon.”

“The salmon fishery collapsed rather quickly after that,” Dr. Garone said. “Overfishing was one cause of the decline. The excessive number of gill nets in the water had not allowed an adequate number of salmon to survive the journey upstream to spawn. But if Native Americans harvested similar quantities of salmon presumably for generations as scholars have argued, then overfishing alone could not have been the main cause of the decline. Instead, overharvesting combined with destruction of the salmon’s spawning beds by the deposition of sediment from the legacy of hydraulic mining appears to account for the diminishment of the runs.”

“Yield from the river fishery continued to decline until the last Sacramento River cannery closed in 1919. By that time, the commercial salmon fishery was already moving to coastal waters and ocean trolling methods gradually replaced gill net fishing on the rivers. At the end of the 1957 season, nearly four decades after the demise of the Delta salmon cannery industry, the state legislature officially terminated commercial gill net fishing in the Delta.”

“Several decades later, when conservationist impulses were ascendant, concern over threatened salmon runs would give rise to important restoration measures for the Delta rivers and floodplains. Salmon populations and ultimately the entire Delta ecosystem would be affected by California’s two most massive water projects, the federal Central Valley Project, the construction of which began in the 1930s, and the State Water Project, begun a generation later in the 1960s.”

Dr. Garone noted that much has been written and published on these two water projects, and it is beyond the scope of this talk to discuss that history in length. “Nonetheless, a brief account of some of the aspects of water development in the Central Valley will set the stage for subsequent water quality problems in the Delta and for late-twentieth century restoration efforts,” he said.

“Early in the 20th century, just as the last major portions of the Delta were being reclaimed, rice production was taking off in the Sacramento Valley to the north. During the 1910s, diversions of Sacramento River water for irrigation doubled. When these larger diversions, which reduced freshwater flow into the delta, coincided with a severe drought in 1920, saltwater intrusion into the Delta became a serious problem. The lines on this map show the extent and the variability of saltwater intrusion during the early to middle years of the 20th century. At one point, by the early 1930s, it had reached throughout almost the entire Delta.”

“In July 1920, the city of Antioch along with 97 Delta residents brought suit against upstream irrigators, primarily rice growers in the Sacramento Valley. In 1922, the California Supreme Court ruled against Antioch and the Delta claimants, but this case, Antioch v. Williams Irrigation District, would have tremendous implications for the future of the Delta, in large part because it led to a new round of discussions in the state about how to grapple with salinity intrusion in the Delta, and those discussions in turn, by the 1930s, led to the Central Valley Project.”

“After much debate that included serious consideration of constructing a physical saltwater barrier for the Delta, California engineers ultimately decided that the construction of a dam and reservoir on the upper Sacramento River with a storage capacity of 4 million acre-feet would be able to provide timed freshwater releases down the Sacramento River to the Delta to hold saltwater intrusion at bay,” said Dr. Garone. “This dam, Shasta Dam, was the lynchpin of the Federal Central Valley Project, a massive, multipurpose, hydraulic enterprise designed to transport water from the relatively moist Sacramento Valley to the more arid San Joaquin Valley. The US Bureau of Reclamation constructed Shasta Dam between 1938 and 1945, and although freshwater releases from the dam remedied the problem for a time of saltwater intrusion into the Delta, the Central Valley Project also put in place an infrastructure by which the San Joaquin Valley and southern California could access water originating in northern California.”

“After much debate that included serious consideration of constructing a physical saltwater barrier for the Delta, California engineers ultimately decided that the construction of a dam and reservoir on the upper Sacramento River with a storage capacity of 4 million acre-feet would be able to provide timed freshwater releases down the Sacramento River to the Delta to hold saltwater intrusion at bay,” said Dr. Garone. “This dam, Shasta Dam, was the lynchpin of the Federal Central Valley Project, a massive, multipurpose, hydraulic enterprise designed to transport water from the relatively moist Sacramento Valley to the more arid San Joaquin Valley. The US Bureau of Reclamation constructed Shasta Dam between 1938 and 1945, and although freshwater releases from the dam remedied the problem for a time of saltwater intrusion into the Delta, the Central Valley Project also put in place an infrastructure by which the San Joaquin Valley and southern California could access water originating in northern California.”

“As both agricultural production and population expanded rapidly in California during subsequent decades, the need for freshwater diversions from the Delta to the San Joaquin Valley and the cities of southern California increased. The State Water Project, rivaling the Federal Central Valley Project in size, was constructed during the 1960s, significantly increasing water exports south of the Delta. As a result, saltwater intrusion has reemerged as a significant problem. During periods of low flow and drought, saltwater from the ocean advances inland as far as the pumping plants on the southern edge of the Delta, resulting in the need to temporarily reduce or cease pumping into the federal or state aqueducts that carry water southward.”

“As both agricultural production and population expanded rapidly in California during subsequent decades, the need for freshwater diversions from the Delta to the San Joaquin Valley and the cities of southern California increased. The State Water Project, rivaling the Federal Central Valley Project in size, was constructed during the 1960s, significantly increasing water exports south of the Delta. As a result, saltwater intrusion has reemerged as a significant problem. During periods of low flow and drought, saltwater from the ocean advances inland as far as the pumping plants on the southern edge of the Delta, resulting in the need to temporarily reduce or cease pumping into the federal or state aqueducts that carry water southward.”

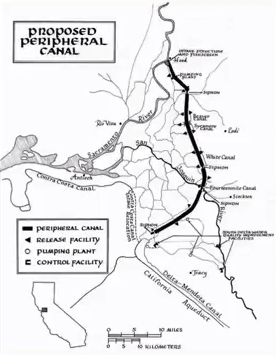

“Solutions to the conflicting demands of providing drinking and irrigation water to southern California while protecting the Delta remain elusive. As early as 1965, in response to the demand of San Joaquin Valley agriculturalists and southern California municipalities for guaranteed supply of fresh water, federal and state agencies proposed a plan for an unlined canal 43 miles long, 400 feet wide, and 30 feet deep that would transport fresh Sacramento River around, rather than through, the Delta. This so-called Peripheral Canal became a flashpoint in north/south tensions over water resources for the next 17 years, spanning the governorships of Pat Brown, Ronald Reagan, and Jerry Brown – the first time. Ultimately, legislation for the canal was decisively defeated by California voters in a 1982 referendum.”

“Solutions to the conflicting demands of providing drinking and irrigation water to southern California while protecting the Delta remain elusive. As early as 1965, in response to the demand of San Joaquin Valley agriculturalists and southern California municipalities for guaranteed supply of fresh water, federal and state agencies proposed a plan for an unlined canal 43 miles long, 400 feet wide, and 30 feet deep that would transport fresh Sacramento River around, rather than through, the Delta. This so-called Peripheral Canal became a flashpoint in north/south tensions over water resources for the next 17 years, spanning the governorships of Pat Brown, Ronald Reagan, and Jerry Brown – the first time. Ultimately, legislation for the canal was decisively defeated by California voters in a 1982 referendum.”

“Diversions south of the Delta from the Central Valley Project and the State Water Project have led to prolonged problems with declining water quality and native fish populations, including the Central Valley salmon runs. That led in part to the passage of the Delta Protection Act of 1992, which created the Delta Protection Commission. The following year, the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the California Fish and Game Commission declared the Delta smelt, a native fish endemic to the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary, an endangered species.”

“Currently, the Bay Delta Conservation Plan, or BDCP, promotes the co-equal goals of protecting, restoring, and enhancing the Delta ecosystem and creating a more reliable water supply for the state,” said Dr. Garone. “Since 2009, the Delta Stewardship Council has been charged with achieving these co-equal goals, but the BDCP has become mired in acrimonious debate over its proposed water conveyance facility, otherwise known as the Delta tunnels.” (Maven note: What was once the BDCP has been divided into two parts: California Water Fix for the tunnels and water infrastructure and California Eco Restore for the habitat restoration.)

“Now as a historian and not a policymaker, it’s not my intention to debate that controversial plan today,” he said. “Rather, my goal is to provide the background history for the Delta’s ongoing water supply and water quality problems, so that said, I’ll devote the last section of this environmental history talk to successes that have been achieved by protecting habitat, especially wetland habitat, along the Delta’s margins.”

“The Central Valley’s estimated 4 million acres of permanent and seasonal wetlands at the time of statehood were reduced to only several hundred thousand acres by the middle of the 20th century, primarily because of conversion to agriculture. But by the early decades of that century, the four great North American transcontinental flyways for migratory waterfowl and other avian species had been discovered.”

“The Pacific Flyway, the westernmost of the four, stretches from the arctic and subarctic regions of Alaska and western Canada, across the western United States, to western Mexico and beyond. For millions of years, the migratory waterfowl of the flyway have bred in the far North, during the short arctic summer, and then migrated southward during the fall to overwinter in places with more moderate climates. The maintenance of this annual migration depends on the condition of both the northern breeding grounds and the southern wintering grounds. And the primary wintering grounds of the Pacific Flyway are located in the Central Valley of California, including the Delta and Suisun Marsh.”

“The Pacific Flyway, the westernmost of the four, stretches from the arctic and subarctic regions of Alaska and western Canada, across the western United States, to western Mexico and beyond. For millions of years, the migratory waterfowl of the flyway have bred in the far North, during the short arctic summer, and then migrated southward during the fall to overwinter in places with more moderate climates. The maintenance of this annual migration depends on the condition of both the northern breeding grounds and the southern wintering grounds. And the primary wintering grounds of the Pacific Flyway are located in the Central Valley of California, including the Delta and Suisun Marsh.”

“As the threat to migratory birds of disappearing wetland habitat became clearer, California began to halt, and at times reverse, the loss of its wetlands by creating state and national wildlife refuges, as well as protecting significant expanses of privately owned wetlands. As a result of these efforts, today the valley still supports an astonishing 60% of all the wintering waterfowl of the Pacific Flyway, the total population of which has averaged about 6.6 million birds since record keeping began back in 1955.”

“As the threat to migratory birds of disappearing wetland habitat became clearer, California began to halt, and at times reverse, the loss of its wetlands by creating state and national wildlife refuges, as well as protecting significant expanses of privately owned wetlands. As a result of these efforts, today the valley still supports an astonishing 60% of all the wintering waterfowl of the Pacific Flyway, the total population of which has averaged about 6.6 million birds since record keeping began back in 1955.”

Narrowing the focus just to the Delta, Dr. Garone discussed four of the key protected areas:

Narrowing the focus just to the Delta, Dr. Garone discussed four of the key protected areas:

- Cosumnes River Preserve: “Since the Nature Conservancy formally dedicated the Cosumnes River Preserve in 1987, the preserve has grown to more than 50,000 acres of permanent and seasonal wetlands, as well as private agricultural and grazing lands that are managed in wildlife-compatible ways to attract wintering waterfowl. Over the years, the mission, as well as the size of the preserve, has expanded to include a wide variety of both animals and plants and the restoration of a range of ecosystems, including floodplains, which have proven to be of particular importance for native fish species such as the Chinook salmon and Sacramento splittail.”

- Stone Lakes National Wildlife Refuge: “The Stone Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1994, currently protects over 11,000 acres of a rich mosaic of habitats, including wetlands, vernal pools, grasslands, valley oak woodlands, and riparian forests, from the pressures of urban development sprawling south of Sacramento.”

Yolo Bypass Wildife Area: “The Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area, established in 1997 and now encompassing approximately 16,000 acres, is managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to be completely compatible with the bypass’s flood control function, even as it is restored to the wetland habitat for Pacific Flyway ducks, geese, and shorebirds that it had been prior to reclamation. In addition, the Yolo Bypass seasonal floodplain— much like the Cosumnes River floodplain—has been found to support juvenile Chinook salmon and spawning Sacramento splittail, as well as 13 other native fish species and 42 fish species in total. So here, as elsewhere in the Central Valley, wetlands, once drained and reclaimed as an obstacle to development, are proving compatible with other land uses, including the maintenance of California’s hydraulic infrastructure.”

Yolo Bypass Wildife Area: “The Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area, established in 1997 and now encompassing approximately 16,000 acres, is managed by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to be completely compatible with the bypass’s flood control function, even as it is restored to the wetland habitat for Pacific Flyway ducks, geese, and shorebirds that it had been prior to reclamation. In addition, the Yolo Bypass seasonal floodplain— much like the Cosumnes River floodplain—has been found to support juvenile Chinook salmon and spawning Sacramento splittail, as well as 13 other native fish species and 42 fish species in total. So here, as elsewhere in the Central Valley, wetlands, once drained and reclaimed as an obstacle to development, are proving compatible with other land uses, including the maintenance of California’s hydraulic infrastructure.”- Woodbridge Ecological Reserve: “Another Delta refuge of importance, the Woodbridge Ecological Reserve, also known as the Isenberg Sandhill Crane Reserve, provides habitat for greater and lesser sandhill cranes, the former of which are listed as a threatened species in California.”

“Together, these various refuges, created through the efforts of nonprofit organizations and the state and federal governments, have restored relatively small but ecologically important parts of the Delta, and although these refuges are managed landscapes, and that must always be kept in mind, they offer a glimpse of the Delta and its abundance of wildlife in a time before reclamation.”

“Today, after more than a century and a half of reclamation and development, the Delta remains a garden in many ways, supporting over one hundred crops on some 500,000 acres of agricultural land,” said Dr. Garone. “But despite its tremendous bounty, the Delta is also much more than a garden. Among its many land uses, the Delta now includes a variety of types of protected lands, including some on which agriculture is managed to be compatible with wildlife. At the same time, the Delta lies at the epicenter of disputes over water allocation and distribution and suffers from a prolonged decline in the quality of its water and in the ability of its aquatic ecosystem to support life.”

“All of these accomplishments and challenges point to a robust, yet still fragile, contemporary Delta that needs our protection, and that is the message that all of our narratives from this project are trying to convey to a general lay audience – to increase support and awareness of the Delta, so on that note, I’ll conclude and say thank you.”

Discussion highlights …

Question: How important do you think the Suisun Marsh was? It’s fairly unique, in that a lot of the basins would dry up towards the end of the summer and fall, and it was persistent wetland, flooded the whole time, so it seems very unique.

“The Suisun Marsh is very important,” responded Dr. Garone, noting that in the interest of time, he didn’t speak of it today but he did write about it at length in his narrative and in some other publications as well. “It’s tremendously important because from a wildlife perspective, it’s a place that can hold waterfowl in the fall until the Central Valley marshes are flooded in the winter and it served that purpose for a very long time. It also has a very interesting history because, much like the Delta, for a relatively brief period in the late 19th century, Suisun Marsh was drained and converted to agriculture, and it looked like it would follow the same trajectory as the Delta. Of course, Suisun Marsh is closer to the bay, and saltwater intrusions there were more frequent and more destructive and eventually that had to be abandoned. The marsh was re-flooded, and we end up with the managed marsh that we have today. So yes, it’s very important. I just didn’t have time to talk about it today.”

Question: You mentioned that this is being prepared for lay audiences, and I’m wondering if you have presented it to lay audiences and what context and what kind of reception you’ve gotten?

“All through this past year, as we were developing these narratives, we met with interested parties all through the Delta and around its margins, presenting the research,” responded Dr. Garone. “The ultimate goal of this was not to just produce four narratives by the four scholars that will then be filed away somewhere, but rather, the narratives are now being used by museums and historical societies in and around the Delta to create displays and exhibits, so that this information can be presented to a broad public, to give people a greater awareness of the Delta, and then, of course, in turn, hopefully that will lead to more motivation for protection of the Delta. So that’s why I say it was for a lay audience. I’ve written more technical things elsewhere, but this whole narrative was written in kind of a lay way and to reach as wide as possible of an audience.”

For more information …

- Click here for Dr. Garone’s essay, Managing the Garden: Agriculture, Reclamation, and Restoration in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta

- Click here for much more information on the Delta Narratives project.

- Click here to view all Delta Narratives articles posted on the Notebook.

Help Maven bridge the funding gap!

Help Maven bridge the funding gap!

Your help is needed for Maven’s Notebook to continue operations in 2016.