A look at potential regulation content: Governance, coordination agreements, and sustainable groundwater management planning

At the December meeting of the California Water Commission, Senior Engineering Geologist for the Department of Water Resources Trevor Joseph updated the California Water Commission on potential regulation content of the groundwater sustainability plan and alternative regulation that is currently under development.

At the December meeting of the California Water Commission, Senior Engineering Geologist for the Department of Water Resources Trevor Joseph updated the California Water Commission on potential regulation content of the groundwater sustainability plan and alternative regulation that is currently under development.

Trevor Joseph began by stating the Department of Water Resources’ regulatory responsibility. “By June 1st, 2016, we need to adopt emergency regulations for evaluating groundwater sustainaability plans (GSPs), the implementation of GSPs and coordination agreements,” he said. “The regulations shall identify the specific requirements for the required plan components, the additional plan elements, and the coordination of GSPs, and other information that we feel is necessary.”

Trevor Joseph began by stating the Department of Water Resources’ regulatory responsibility. “By June 1st, 2016, we need to adopt emergency regulations for evaluating groundwater sustainaability plans (GSPs), the implementation of GSPs and coordination agreements,” he said. “The regulations shall identify the specific requirements for the required plan components, the additional plan elements, and the coordination of GSPs, and other information that we feel is necessary.”

The Department is also required to prepare best management practices for sustainable groundwater management, which is due in 2017. “A lot of folks are asking how does that BMP document relate to regulations, and the way we look at it is that the emergency regulations are really the minimum standards, and the best management practice will be guidance for implementing those GSPs,” he said.

“All 127 high and medium priority basins throughout the state need to be covered by GSPs or a combination of GSPs, alternatives, or adjudications,” Mr. Joseph said. “When we look at the state, we feel the vast majority of it will be covered by GSPs. We feel that alternatives will likely be a subset of those basins.”

There are really three options for covering those basins: there’s a single groundwater sustainability agency (GSA) with a single GSP, multiple GSAs coordinating and preparing a single GSP, and multiple GSAs and multiple GSPs with a coordination agreement.

There are really three options for covering those basins: there’s a single groundwater sustainability agency (GSA) with a single GSP, multiple GSAs coordinating and preparing a single GSP, and multiple GSAs and multiple GSPs with a coordination agreement.

He presented the slide showing the potential regulation content organized into chapters, and said that today’s presentation would focus on those chapters related to governance, coordination, and sustainable groundwater management planning. He also noted that meetings with advisory groups are still ongoing, the regulations are still in the iterative process and subject to change.

Governance

Governance is covered in SGMA’s Chapter 6 which lists a series of requirements for adoption or amendment of a plan and public notification of participation; SGMA’s Chapter 4 outlines a series of governance and stakeholder requirements when forming a GSA, Mr. Joseph said.

Governance is covered in SGMA’s Chapter 6 which lists a series of requirements for adoption or amendment of a plan and public notification of participation; SGMA’s Chapter 4 outlines a series of governance and stakeholder requirements when forming a GSA, Mr. Joseph said.

“What we feel should be in regulations is a description of proof of adoption which is a requirement in SGMA,” he said “We want a description of the legal authority that a GSA has to prepare and implement a GSP; we also want to see a description of roles and responsibilities, and perhaps in a communication plan that outlines how the GSA will conduct the implementation of the plan and identify key milestones in terms of stakeholder involvement.”

“We want a description of how the beneficial use was considered and users of groundwater were engaged in the development of the GSP,” he said. “That is again something that’s found in Chapter 4 as it relates to GSA development but we feel it is incredibly important for the development of the GSP. Then finally, we’re going to look at stakeholder comments when considering and evaluating a GSP.”

He noted that there will be more detail in the regulations themselves, but those are the highlights as it relates to governance and stakeholder involvement.

Coordination

There are two types of coordination that will be defined in the regulations: intra-basin coordination which is coordination between multiple GSAs within existing basin or subbasin, and inter-basin coordination, which is coordination between two hydraulically connected basins.

There are two types of coordination that will be defined in the regulations: intra-basin coordination which is coordination between multiple GSAs within existing basin or subbasin, and inter-basin coordination, which is coordination between two hydraulically connected basins.

With interbasin coordination, which is the coordination between multiple GSAs in an existing basin or subbasin, it could be multiple GSAs completing a single GSP or multiple GSAs completing multiple GSPs within that basin or subbasin. “We feel strongly that there be whole basin requirements in that coordination,” Mr. Joseph said. “We don’t want to see a piecemealed approach to development and submittal of those components. For example, there will be a water budget requirements or description of a hydrologic conceptual model. We don’t, as a Department, to take all the individual pieces and try to make sense of them when they come to us in a coordination agreement. We feel that those should be presented and developed on a basin wide or subbasin wide level. So a lot of coordination will be necessary to make that happen, but we think its imperative to get a complete story for the basin or subbasin.”

With interbasin coordination, which is the coordination between multiple GSAs in an existing basin or subbasin, it could be multiple GSAs completing a single GSP or multiple GSAs completing multiple GSPs within that basin or subbasin. “We feel strongly that there be whole basin requirements in that coordination,” Mr. Joseph said. “We don’t want to see a piecemealed approach to development and submittal of those components. For example, there will be a water budget requirements or description of a hydrologic conceptual model. We don’t, as a Department, to take all the individual pieces and try to make sense of them when they come to us in a coordination agreement. We feel that those should be presented and developed on a basin wide or subbasin wide level. So a lot of coordination will be necessary to make that happen, but we think its imperative to get a complete story for the basin or subbasin.”

There is a description in SGMA that states that these entities shall use the same data and methodology as it relates to these requirements, and there’s been a lot of discussion with advisory groups in terms of what does ‘same’ really mean, Mr. Joseph said. “From our perspective, there are items that should be the same; there should be one sustainable yield for the entire basin or subbasin. There should be one description and analysis of total water use, and a few other items.”

There is a description in SGMA that states that these entities shall use the same data and methodology as it relates to these requirements, and there’s been a lot of discussion with advisory groups in terms of what does ‘same’ really mean, Mr. Joseph said. “From our perspective, there are items that should be the same; there should be one sustainable yield for the entire basin or subbasin. There should be one description and analysis of total water use, and a few other items.”

However there are a lot of questions related to modeling, he noted. “Some basins are relatively large; historically they’ve used different models, and they may be sustainable, so we don’t want to develop a process or interpret same in such a manner that it forces them to use one model and abandon the other. So what we feel is most important is that they agree on the assumptions and the outcome in terms of how they look at total water use and these requirements, but we don’t prescribe how exactly they get there.”

With intra-basin coordination, which is coordination across those basin boundary lines, the Department needs to make an assessment as to whether or not one basin adversely impacts another to reach their sustainability goal, he said. “There are no requirements laid out in SGMA, so we are laying them out in terms of what we feel is necessary in regulations, and it really comes down to some technical items such as water budget information; also if a basin boundary is a stream or a creek, we want an estimate of the recharge and general agreement on that between adjacent GSPs; a description on how they intend to manage groundwater so that they don’t adversely impact one another; and then also a conflict resolution description.”

With intra-basin coordination, which is coordination across those basin boundary lines, the Department needs to make an assessment as to whether or not one basin adversely impacts another to reach their sustainability goal, he said. “There are no requirements laid out in SGMA, so we are laying them out in terms of what we feel is necessary in regulations, and it really comes down to some technical items such as water budget information; also if a basin boundary is a stream or a creek, we want an estimate of the recharge and general agreement on that between adjacent GSPs; a description on how they intend to manage groundwater so that they don’t adversely impact one another; and then also a conflict resolution description.”

Mr. Joseph pointed out is that the Department does not feel that the requirements are the same for intra-basin and inter-basin coordination. “A lot of advisory groups thought perhaps it should be; others thought that it certainly shouldn’t be, but we don’t feel it’s the exact same requirements as intra-basin coordination.”

Sustainable Groundwater Management Planning

“There are terms defined in SGMA that help us develop a framework for how we will evaluate plans and progress and those terms are sustainability goal, sustainable groundwater management, and sustainable yield,” he said. “In many cases as defined in SGMA, they are very interrelated or depend on one another. It really comes down to sustainable yield and avoiding undesirable results, and so these undesirable results listed here are really the outcomes in terms of meeting sustainability. If local agencies and GSAs avoid these undesirable results at significant and unreasonable levels, then they are managing the basin sustainably.”

“There are terms defined in SGMA that help us develop a framework for how we will evaluate plans and progress and those terms are sustainability goal, sustainable groundwater management, and sustainable yield,” he said. “In many cases as defined in SGMA, they are very interrelated or depend on one another. It really comes down to sustainable yield and avoiding undesirable results, and so these undesirable results listed here are really the outcomes in terms of meeting sustainability. If local agencies and GSAs avoid these undesirable results at significant and unreasonable levels, then they are managing the basin sustainably.”

“Now significant and unreasonable is not defined in SGMA, and so that’s where it becomes more challenging and where we have developed a framework for how to evaluate whether or not undesirable results are significant or unreasonable,” he said.

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act states that GSAs shall develop measurable objectives and interim milestones in increments of every five years to achieve the sustainability goal, which is avoiding these undesirable results at significant and unreasonable levels within the 20 years of implementation of the plan, he said. Measurable objectives are similar to prior groundwater management plan basin management objectives; a measurable objective is a management statement and a measurable metric that is defined at interim milestones for each undesirable result, he said.

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act states that GSAs shall develop measurable objectives and interim milestones in increments of every five years to achieve the sustainability goal, which is avoiding these undesirable results at significant and unreasonable levels within the 20 years of implementation of the plan, he said. Measurable objectives are similar to prior groundwater management plan basin management objectives; a measurable objective is a management statement and a measurable metric that is defined at interim milestones for each undesirable result, he said.

A minimum threshold is defined as the point below which an undesirable result is causing significant and unreasonable levels in the basin. “We want to see those minimum thresholds in a quantitative and not a qualitative manner,” he said.

There is not a detailed definition of ‘significant and unreasonable’ in SGMA; since each basin is unique, this will have to be determined at a local level, he said. “A reduction in storage might be significant and unreasonable in a small basin based on a small volume, and in a larger basin, it may take quite a bit of pumping to create a reduction in storage that is significant and unreasonable, and so there’s a lot to these definitions of undesirable results that we feel where that threshold is should be locally defined. It should be developed and submitted locally.”

There is not a detailed definition of ‘significant and unreasonable’ in SGMA; since each basin is unique, this will have to be determined at a local level, he said. “A reduction in storage might be significant and unreasonable in a small basin based on a small volume, and in a larger basin, it may take quite a bit of pumping to create a reduction in storage that is significant and unreasonable, and so there’s a lot to these definitions of undesirable results that we feel where that threshold is should be locally defined. It should be developed and submitted locally.”

Mr. Joseph said that they did hear from advisory groups who felt that the Department should try to develop quantitative minimum standards for each of the undesirable results. “Frankly that’s impossible in the amount of time, given the complexity of the differences between basins, and what I mean by that is that if we tried to approach and develop a minimum water level in each basin, it would be incredibly problematic and require a lot of data and consensus and there certainly isn’t time for that,” he said. “However, we do feel that a minimum threshold for each undesirable result should be developed and submitted in the GSP, and we would like again to see a description of how the beneficial use and users of groundwater were considered when setting that measurable threshold.”

“We also feel that should be a quantitative measure; for groundwater levels, we want to see that in feet/mean sea level, we don’t want to see a value in some qualitative term,” he said. “For reduction of storage, we want to see it in a change of storage and what is an appropriate change of storage that’s not significant and unreasonable for that basin.”

“We also feel that should be a quantitative measure; for groundwater levels, we want to see that in feet/mean sea level, we don’t want to see a value in some qualitative term,” he said. “For reduction of storage, we want to see it in a change of storage and what is an appropriate change of storage that’s not significant and unreasonable for that basin.”

“The minimum thresholds are important because it’s important for the GSA to know where impacts are truly going to occur in the basin and what the minimum level is as it relates to these undesirable results,” he said. “From our perspective, we’re required to evaluate these undesirable results and so if that minimum level is established, then we know if that’s being exceeded and not being corrected, that that might be a place for state intervention; otherwise it becomes really subjective in terms of where that state intervention may occur.”

Commissioner David Orth clarifies that on the groundwater elevation issue, the Department will be more focused on regions within basins than a basin-wide average elevation. “Some of our basins in the valley have ranges of depth to groundwater of 50 feet out to several hundred feet, so it seems like we have to deal with that within management zones or regional areas within a basin,” he says.

“The number of thresholds is really most appropriate to be developed by the local agencies,” Mr. Joseph said. “It’s possible in a really small basin that perhaps one threshold could be established. In a basin where water levels fluctuate greatly and you’re trying to maintain water levels for self supply or municipal or industrial needs, then perhaps there’s a threshold in that area of the basin that they really can’t go below otherwise they’re not meeting the needs of that community, but elsewhere in the basin, there aren’t really undesirable results and the threshold is not needed. It becomes challenging in terms of application and we definitely don’t think one size fits all, even within an existing basin or subbasin.”

Another commissioner asks about the time frame – short term or long term?

“With a minimum threshold, it’s kind of that floor that below that level, impacts are really occurring,” Mr. Joseph said. “So with measurable objectives and defining where you want to be, you’d want to manage a buffer, so that you can manage to those cyclical hydraulic nature of changing groundwater levels. We also feel that minimum threshold jumps ahead but that it can change over time and should change over time. Initially, there may not be a lot of data to substantiate where that minimum threshold should be. We do feel that uncertainty should be reduced over the implementation period, but that agencies will be learning and refining that threshold over time.”

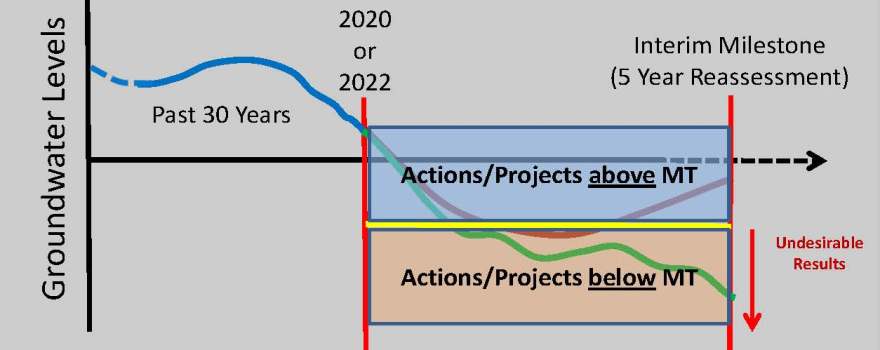

He then gave an example using groundwater levels as an example. “The SGMA accountability date is the date at which GSAs need to begin to address undesirable results in the basin, and then they need to achieve sustainability by either 2040 or 2042, depending upon whether or not they are in a critically overdrafted basin, so this is a non-critically overdrafted basin and they need to meet that goal by 2042,” he said. “So looking at the past hydrology, if they made no actions in this example, groundwater levels would continue to decline, so we’re asking that they establish a minimum threshold. It’s dashed here because really there’s a lot of uncertainty and that will refine over time.”

He then gave an example using groundwater levels as an example. “The SGMA accountability date is the date at which GSAs need to begin to address undesirable results in the basin, and then they need to achieve sustainability by either 2040 or 2042, depending upon whether or not they are in a critically overdrafted basin, so this is a non-critically overdrafted basin and they need to meet that goal by 2042,” he said. “So looking at the past hydrology, if they made no actions in this example, groundwater levels would continue to decline, so we’re asking that they establish a minimum threshold. It’s dashed here because really there’s a lot of uncertainty and that will refine over time.”

“But that is initially the minimum threshold for the basin, so in this example, they’ve recognized that they can actually manage water levels perhaps a little lower than January 1, 2015 in our basin, and it still doesn’t create undesirable results,” he said.

“But that is initially the minimum threshold for the basin, so in this example, they’ve recognized that they can actually manage water levels perhaps a little lower than January 1, 2015 in our basin, and it still doesn’t create undesirable results,” he said.

He noted that the brown line illustrates the projected path that the GSA intends to take to meet its measurable objective over that 20 year implementation period. “In this example, they are showing that they are going to have a period where declines are going to occur until they get projects up to speed, and then they anticipate this linear progression until they reach this new water level by 2042.”

He reminded that the minimum threshold is important in terms of what really causes impacts within that basin, and here it’s shown as fluctuating because it’s refined over the course of collecting data and learning about the basin. He noted that actual water levels are shown in blue, and the idea is if they stay above that yellow line and avoid those minimum thresholds, then they are avoiding that significant and unreasonable condition in the basin.

“These two lines here show a band of uncertainty; they narrow towards that 2040 SGMA sustainability date, because we feel that it’s obvious there will be a lot of uncertainty early in the implementation of these plans, but by the end, they should have less uncertainty. They should really understand their basin and know where that minimum threshold is.”

“These two lines here show a band of uncertainty; they narrow towards that 2040 SGMA sustainability date, because we feel that it’s obvious there will be a lot of uncertainty early in the implementation of these plans, but by the end, they should have less uncertainty. They should really understand their basin and know where that minimum threshold is.”

So the GSP must adhere to the framework as described, Mr. Joseph said. “Their establishment of the minimum threshold and their trajectory to meet their sustainability goal must pass the reasonable test. We’re not going to give up our authority to look at these plans and describe what’s reasonable here, but there is a lot of GSA discretion and flexibility in our mind. The minimum thresholds and their planned path is proposed by the GSA, it’s locally defined, and we recognize that it’s site specific.”

So the GSP must adhere to the framework as described, Mr. Joseph said. “Their establishment of the minimum threshold and their trajectory to meet their sustainability goal must pass the reasonable test. We’re not going to give up our authority to look at these plans and describe what’s reasonable here, but there is a lot of GSA discretion and flexibility in our mind. The minimum thresholds and their planned path is proposed by the GSA, it’s locally defined, and we recognize that it’s site specific.”

“Actions above or below the minimum threshold – they are going to need to implement actions and projects, and this is nothing new,” he said. “Existing groundwater management plans have actions and projects; we want them organized whether or not they are below that minimum threshold because they may need more severe actions if they are below the minimum threshold to get above those impacts.”

Mr. Joseph said that a contingency plan is also going to be necessary. “A contingency plan is a series of actions that are demand-reduction focused, and we feel that’s important because if they are implementing their existing set of actions and they are not effective, they need to pull that contingency plan off the shelf and implement that. That’s probably their last opportunity to avoid state board intervention.”

Monitoring

There needs to be an adequate number of monitoring sites, Mr. Joseph said. “CASGEM is a great foundation for establishing a minimum standard for groundwater level monitoring,” he said. “We would like to see quarterly frequency … we do feel that may need to be either increased or could be decreased depending upon the severity of the undesirable results. So when we look at these, one-size does not fit all, so we want to make sure that we have some flexibility in the regulations so that there’s not just this standard that has to be met regardless of the severity of the undesirable results in the basin.”

There needs to be an adequate number of monitoring sites, Mr. Joseph said. “CASGEM is a great foundation for establishing a minimum standard for groundwater level monitoring,” he said. “We would like to see quarterly frequency … we do feel that may need to be either increased or could be decreased depending upon the severity of the undesirable results. So when we look at these, one-size does not fit all, so we want to make sure that we have some flexibility in the regulations so that there’s not just this standard that has to be met regardless of the severity of the undesirable results in the basin.”

Mr. Joseph said that 98% of high and medium priority basins are now covered by CASGEM. “As a foundation, there’s 46,000 monitoring wells in the DWR water data library, but this is misleading in that we have records and data, but well construction information for very few. Of this 46,000, 5600 have been identified as CASGEM wells, so again a great foundation in terms of a monitoring network.”

Mr. Joseph said that 98% of high and medium priority basins are now covered by CASGEM. “As a foundation, there’s 46,000 monitoring wells in the DWR water data library, but this is misleading in that we have records and data, but well construction information for very few. Of this 46,000, 5600 have been identified as CASGEM wells, so again a great foundation in terms of a monitoring network.”

There is a certain standard that needs to be met for CASGEM wells. “We want to understand the location, the depth, and where they are screened as these are all important details in terms of monitoring the actual aquifers where undesirable results may be occurring, so the necessary information will be included in the regulations,” he said. “In terms of a plan view, for monitoring wells, we want the well construction information, an adequate period of record, and that they are screened in the appropriate aquifers for those undesirable results.”

There is a certain standard that needs to be met for CASGEM wells. “We want to understand the location, the depth, and where they are screened as these are all important details in terms of monitoring the actual aquifers where undesirable results may be occurring, so the necessary information will be included in the regulations,” he said. “In terms of a plan view, for monitoring wells, we want the well construction information, an adequate period of record, and that they are screened in the appropriate aquifers for those undesirable results.”

Compliance wells are subset of wells will be used to measure progress and sustainability, he said. “Again, providing a statewide standard is near impossible and that’s why we’re not very prescriptive here. We want to see a submittal from the GSAs in terms of what they feel is appropriate in terms of the number of compliance wells throughout the basin, but it needs to be adequate to monitor the undesirable results. We feel that is important that each compliance well have a minimum threshold in terms of levels for identifying those impacts and for compliance purposes.”

Compliance wells are subset of wells will be used to measure progress and sustainability, he said. “Again, providing a statewide standard is near impossible and that’s why we’re not very prescriptive here. We want to see a submittal from the GSAs in terms of what they feel is appropriate in terms of the number of compliance wells throughout the basin, but it needs to be adequate to monitor the undesirable results. We feel that is important that each compliance well have a minimum threshold in terms of levels for identifying those impacts and for compliance purposes.”

Next steps

Mr. Joseph said he would return in January to go through the other components. “Our timeline is we’re looking to have a draft emergency regulation document out in late January, possible early February in order to meet our legislative deadline of having the final regulations hopefully adopted by June 1 of 2016.”

For more information …

- DWR Sustainable Groundwater Management (SGM): http://www.water.ca.gov/groundwater/sgm/index.cfm

- DWR GSP Emergency Regulation Website: http://www.water.ca.gov/groundwater/sgm/gsp.cfm

- Subscribe to DWR SGM Email List: http://www.water.ca.gov/groundwater/sgm/subscribe.cfm

- DWR Region Office Contacts: http://www.water.ca.gov/groundwater/gwinfo/contacts.cfm

- Questions or Comments: sgmps@water.ca.gov

Help Maven bridge the funding gap!

Help Maven bridge the funding gap!

Your help is needed for Maven’s Notebook to continue operations in 2016.