Committee hears about progress made on collaborative science in the Delta; Dr. Steven Brandt presents the Fishes and Flows report

At the Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee (DPIIC) meeting held November 16th, committee members were briefed on the progress made on coordinating science efforts in the Delta, as well as the latest report from the Delta Independent Science Board, Flows and Fishes in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta: Research Needs in Support of Adaptive Management.

(This is the last of three part coverage from the meeting. Part 1 is here: Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee, pt 1: Delta Challenges: Complex, Chaotic or Simply Cantankerous. Part 2 is here: Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee, Pt 2: An update on California Eco Restore and the Yolo Bypass)

Implementing “One Delta, One Science”

Chair Randy Fiorini began by reminding the committee that a year ago, the agencies with the Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee agreed to furnish a high level science policy person to form a Delta Science Workgroup. “The work that they have accomplished in a year’s time is remarkable and a testament to the opportunities that exist if you bring people together from multiple agencies that don’t often have a time to meet at that level about specific issues, the work that they can produce,” he said.

Chair Randy Fiorini began by reminding the committee that a year ago, the agencies with the Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee agreed to furnish a high level science policy person to form a Delta Science Workgroup. “The work that they have accomplished in a year’s time is remarkable and a testament to the opportunities that exist if you bring people together from multiple agencies that don’t often have a time to meet at that level about specific issues, the work that they can produce,” he said.

Dr. Cliff Dahm, Delta Lead Scientist, then began the agenda item by noting that ‘One Delta, One Science’ was the theme of the Delta Science Plan, which was finished in 2013 under the leadership of Dr. Peter Goodwin. “It has as a vision of using collaborative science to support management decisions that address the challenges associated with achieving the coequal goals in the Delta,” he said. “The goals for the Delta Science Plan are to strengthen and unify the Delta science community; assure the credibility, relevance, and legitimacy of Delta science; and to provide tools, organizational structures, mechanisms for scientists, policy makers, managers, stakeholders, and the public that will help them more effectively collaborate on turning Delta science into effective action.”

The prioritized list of science actions that was developed had over 300 suggested science actions, which fell under four thematic areas with a dozen or so subthemes under that, Dr. Dahm said. “That coalescing of that information has had a couple of very interesting outcomes and those outcomes are to come up with at least a short term and a long term science agenda.”

The prioritized list of science actions that was developed had over 300 suggested science actions, which fell under four thematic areas with a dozen or so subthemes under that, Dr. Dahm said. “That coalescing of that information has had a couple of very interesting outcomes and those outcomes are to come up with at least a short term and a long term science agenda.”

Dr. Dahm said they’ve already seen some products from the workgroup: Thematic areas on the science action agenda are being used as areas of emphasis in a proposal solicitation package for doctoral and post-doctoral fellows for fund a number of people to look at specific things; also the Department of Fish and Wildlife used three of the theme areas in their solicitation package to fund $8 million with Prop 1 funds for new research focused on the Delta.

He then turned it over to Taryn Ravazzini, the Committee’s Coordinator, and Dr. Reiner Hoenicke, Deputy Executive Officer of the Delta Science Program, to give the committee an update.

Upon the committee’s endorsement in May, the workgroup moved promptly ahead to organizing and initiating implementation, Ms. Ravazzini began. “We recognized the need to then prioritize and sequence actions according to opportunity and need, and we have met several times since May to coordinate and organize that. I’m very pleased to report that progress is being made on a large number of the actions, and credit really does go to your agencies. We greatly appreciate the level of participation from your policy and science managers who do sit on that workgroup, as well as their commitment to keep coming back and helping us to implement these science actions.”

Upon the committee’s endorsement in May, the workgroup moved promptly ahead to organizing and initiating implementation, Ms. Ravazzini began. “We recognized the need to then prioritize and sequence actions according to opportunity and need, and we have met several times since May to coordinate and organize that. I’m very pleased to report that progress is being made on a large number of the actions, and credit really does go to your agencies. We greatly appreciate the level of participation from your policy and science managers who do sit on that workgroup, as well as their commitment to keep coming back and helping us to implement these science actions.”

Ms. Ravazzini noted that the committee asked for a short list of high‐impact, multi‐benefit science actions for near‐term implementation in 2015‐2016 reflecting a cross‐agency understanding of priority science needs in the Delta, and those science actions are listed in two tables with 4 Key Topics: Table 1 which has 9 actions feasible for rapid‐response implementation and Table 2 which has 6+ actions better suited for longer‐term implementation, such as proposal solicitation.

She noted that the nature of the collaborative list is that it requires fairly consistent review, assessment and in some cases, refinement of the science actions in order to maintain maximum support from the agencies and those stakeholders who are engaged, so the design of these high impact science actions is helping to provide for better science to inform key decisions, such as guiding water operations, selecting sites and designs for ecosystem restoration activities, and managing multiple stressors in the Delta.

She then turned to Dr. Reiner Hoenicke to highlight the workgroup’s specific accomplishments.

Dr. Hoenicke reminded that at the May meeting, the committee endorsed two types of actions: near-term actions and long-term actions. “The difference in implementation timing stems largely from the different funding mechanisms and the preparatory work required,” he said. “One of the advantages of the science program has is that we do have mechanisms that fairly rapidly direct funding to directed actions and that is primarily what causes the different timing of some of these actions.”

A most significant outcome was that immediately after the committee endorsed the topics that the science workgroup had developed, the Department of Fish and Wildlife incorporated three of the four priority topics into their Prop 1 solicitation package for the Delta, he said. “It happened just within days after your last meeting. It was just amazing,” he said. “What the Delta agency science group came up with was then noted as valuable priority research needs and got immediately linked to a member agency’s call for proposals by an available funding mechanism, and that is truly One Delta, One Science in action.”

A most significant outcome was that immediately after the committee endorsed the topics that the science workgroup had developed, the Department of Fish and Wildlife incorporated three of the four priority topics into their Prop 1 solicitation package for the Delta, he said. “It happened just within days after your last meeting. It was just amazing,” he said. “What the Delta agency science group came up with was then noted as valuable priority research needs and got immediately linked to a member agency’s call for proposals by an available funding mechanism, and that is truly One Delta, One Science in action.”

Other notable accomplishments in getting science projects funded:

- The science workgroup was asked to refine the science topics in Table 2 and identify those that could be used to initiate solicitation for a proposal solicitation package for science fellows; the Delta Science Program put money immediately on the table to get the momentum going. The refined topics are listed in page 17 of the report.

- The workgroup and stakeholders bolstered the topic 4 actions that deal with research related to the Delta as a place, with the collaborative work of the Delta Protection Commission and DWR’s FloodSAFE program helping to shape that part of the solicitation.

- Several of the DPIIC agencies and stakeholders have indicated an interest in serving as agency mentors and possibly even funding some of these research efforts, so even more of the projects may end up being funded then originally planned.

“So although we must now wait to see how many of these topics are chosen through these processes; it’s been a very quick turnaround from identification to endorsement to imminent funding of the committee’s request for high impact science actions,” said Dr. Hoenicke.

Another accomplishment is one item under Topic 3G on Table 1, the peer review of the Southwest Fisheries Science Center’s winter-run Chinook salmon life cycle model. “An independent peer review of NOAA’s SW Fisheries Science Center’s life cycle model was conducted earlier this month with a final report providing recommendations to the center at the end of this year, so truly fast turnaround and we’re going to get results back, even before the year is over,” he said. “This was identified by the workgroup as a high impact science action because of the recognition that the model would be used to make a variety of management decisions with wide ranging implications. Building upon that, we can then move forward and define some follow-up specific science and research projects that might actually lead us to direct relevance on how to manage and recover winter-run.”

Dr. Hoenicke said they also took advantage of the installation of the drought barrier to investigate the effects of the barrier on a variety of Delta ecosystem processes. “Specifically in the table, actions 1A the drought effects synthesis, 1B real time decision support, 2C restoration design synthesis, and 3H resources and mechanisms to fund collaborative research – they all benefitted from this opportunity provided by the emergency drought barrier. While DWR worked with the State Water Board to ensure compliance monitoring was in place, the scoping committee found ways to develop work plans through an effective website that we put up so we could communicate our respective ideas and come to decisions how to jointly fund additional studies going beyond just mere compliance monitoring that could take advantage of the modification in the Delta. We essentially treated the barrier as a large scale field laboratory.”

Expedited funding was directed to four projects that investigated the effects of the barrier on hydrodynamics, invasive species, toxic algal blooms, and the food web, especially zooplankton; the studies were packaged this in a way that they created some synergies and ultimately that will feed into the drought synthesis report, Dr. Hoenicke said.

“True to our previous lead scientist’s model of identifying the gaps and providing the glue to fill them, the science program used it’s funding to help get a coherent set of projects off the ground that are now adding to the long-term data record in unique ways; we tried to apply resources where they made the biggest difference,” he said. “This additional work developed collectively will inform not just how to respond to drought but also what changes may occur under various restoration scenarios that may make conditions for invasive species more or less favorable, they may increase or decrease the likelihood of toxic algal blooms and may cause changes in tidal influences on other key ecosystem components and processes.”

“What this effort demonstrates is that through discussion by your agencies in the workgroup and the establishment of the science action list, we’re now creating greater momentum for research that provides multiple benefits that single agencies would be hard pressed to do on their own,” Dr. Hoenicke said. “Together, we’re doing better and together this information is destined to change management approaches like never before.”

Ms. Ravazzini said that the work being done through the workgroup is aiding management decisions and is contributing to the concept of One Delta One Science which was a strongly supported by this Committee at its inaugural meeting back in April of 2014. “So by aligning our Delta science research needs through this effort and identifying those priorities collectively to what policy managers need, working with what science can offer, and understanding both the abilities and limitations on science to remove uncertainties, we are elevating our thinking and figuring out better questions to ask.”

Ms. Ravazzini said that the work being done through the workgroup is aiding management decisions and is contributing to the concept of One Delta One Science which was a strongly supported by this Committee at its inaugural meeting back in April of 2014. “So by aligning our Delta science research needs through this effort and identifying those priorities collectively to what policy managers need, working with what science can offer, and understanding both the abilities and limitations on science to remove uncertainties, we are elevating our thinking and figuring out better questions to ask.”

As implementation of the high impact science action items continues and communications continue on aligning priorities, we’re fostering increased coordination around funding, which is a much needed outcome of this effort, Ms. Ravazzini said. “What we are aiming for is laying the groundwork for a new normal. People having defining the drought as the new normal, well also this level of collaborative work where it’s supporting and enhancing existing efforts, that really is part of becoming the new normal.”

“So from our perspective and the workgroup’s perspective, to sum this up, what we’ve heard is that the workgroup is very valuable, and it does build on those existing collaborative efforts,” she said. “It shows that we do have the ability and the capacity to do decision relevant science, and the work doesn’t end here, so we appreciate the foresight that you had to direct us to do this, because we really have been able to implement quickly. We just want to look for more opportunities where we can keep this momentum moving forward.”

Dr. Dahm then requested that the committee to keep their senior scientists and science program managers engaged in the workgroup. “This workgroup has done some remarkable things in a very short period of time,” he said. “In the next month or two, we’re going to know what kind of science is going to be supported through the fellows program, and we’re going to have information on the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s competitive grants program and what kind of science that will be funded through their effort.”

“What we should do when these two competitions are concluded is do a careful evaluation of what is being supported, evaluate areas that we’re not getting as much support as we had hoped, and actually come back to the committee in 6 months and give you an assessment of where we are and talk strategically about how to get support for some of the areas that are not yet getting support,” concluded Dr. Dahm.

Mike Chotkowski, Delta Science Coordinator with USGS, said that some of the same issues just described have risen to the top in the Interagency Ecological Program priority setting. “Going forward, I would suggest one of the things we should be looking at is making sure that we’re considering all of these different sources of prioritization in doing what we can to make sure the resources are allocated appropriately,” he said. “At some point, there need to be some reckoning in the way resources are being used to make sure that we really are covering the topics that the folks around this table and the IEP directors would like to cover.”

Mike Chotkowski, Delta Science Coordinator with USGS, said that some of the same issues just described have risen to the top in the Interagency Ecological Program priority setting. “Going forward, I would suggest one of the things we should be looking at is making sure that we’re considering all of these different sources of prioritization in doing what we can to make sure the resources are allocated appropriately,” he said. “At some point, there need to be some reckoning in the way resources are being used to make sure that we really are covering the topics that the folks around this table and the IEP directors would like to cover.”

Mary Piepho with the Delta Protection Commission noted that NASA, the USDA, and the Division of Boating and Waterways along with local agencies have come together to better manage aquatic invasive weeds in the Delta. “The area wide management of aquatic weeds in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta is critical for sustainable control in farming areas, critical wildlife habitats, recreational zones, and water conveyance systems important for California agriculture and human health,” she said. “They have come together and tried to break down some of the governmental silos, reach out, and have cross collaboration and identification of funding resources in order to attack the issue. And I daresay there’s been some early success but one that must continue and grow for all of our interests. … I would use that as an example of breaking down the silos and creating greater efficiency and collaboration can actually create greater benefits.”

Mary Piepho with the Delta Protection Commission noted that NASA, the USDA, and the Division of Boating and Waterways along with local agencies have come together to better manage aquatic invasive weeds in the Delta. “The area wide management of aquatic weeds in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta is critical for sustainable control in farming areas, critical wildlife habitats, recreational zones, and water conveyance systems important for California agriculture and human health,” she said. “They have come together and tried to break down some of the governmental silos, reach out, and have cross collaboration and identification of funding resources in order to attack the issue. And I daresay there’s been some early success but one that must continue and grow for all of our interests. … I would use that as an example of breaking down the silos and creating greater efficiency and collaboration can actually create greater benefits.”

Campbell Ingram noted added a cautionary word: “In the circles we’ve been running in lately trying to begin to move money to planning and science, we hear a lot of push back that we know enough and that we don’t need to spend a lot more money to do these things. I think we all fundamentally recognize and understand the need, but I don’t think we’re effectively conveying that message to others. I know that in our efforts, we need to get much better at clearly articulating the five or six very high level scientific questions that are going to be addressing, so that we can convey that to them and they understand what the process is going to do and help them better embrace the need for it.”

Campbell Ingram noted added a cautionary word: “In the circles we’ve been running in lately trying to begin to move money to planning and science, we hear a lot of push back that we know enough and that we don’t need to spend a lot more money to do these things. I think we all fundamentally recognize and understand the need, but I don’t think we’re effectively conveying that message to others. I know that in our efforts, we need to get much better at clearly articulating the five or six very high level scientific questions that are going to be addressing, so that we can convey that to them and they understand what the process is going to do and help them better embrace the need for it.”

Director of the Department of Water Resources Mark Cowin reiterated his support for the workgroup, noting that many of the same folks are also engaged in the Interagency Ecological Program. “We managers of that program have pushed that program to better define itself and come up with a more strategic approach for setting priorities and budgeting and in doing so, reengage the principles from our agencies with the actual work that they are doing and making it more relevant,” he said. “It’s been a little bit painful but it’s been a productive exercise so far, and I feel like we’re making good progress in making IEP more relevant, more efficient, more focused on specific needs.”

Mr. Cowin said a better description of how the multiple science efforts fit together – such as IEP, the Delta Science Program, and the Collaborative Adaptive Management Program which was the outcome of our settlement of long ongoing litigation over biological opinions. “To get the efficiency we’re looking for, I think all of those efforts need to be linked up in some way that we can all understand and describe to our constituents, and so that’s a challenge I’ve given to our IEP managers and I’d like to give it to this group as well, to think about how all of those things fit together,” he said.

Mr. Cowin said a better description of how the multiple science efforts fit together – such as IEP, the Delta Science Program, and the Collaborative Adaptive Management Program which was the outcome of our settlement of long ongoing litigation over biological opinions. “To get the efficiency we’re looking for, I think all of those efforts need to be linked up in some way that we can all understand and describe to our constituents, and so that’s a challenge I’ve given to our IEP managers and I’d like to give it to this group as well, to think about how all of those things fit together,” he said.

With respect to the collective understanding of the Delta wide science required, Mr. Cowin said that in his mind, there’s a linkage between future funding for these programs and just who that collective understanding belongs to. “With all due respect to Congress and the way that they are providing funding for our federal agencies, I’m not expecting new boatloads of money to come from the federal government to support this science effort,” he said. “Notwithstanding the special funding we’ve received for drought response, I’m not expecting the state to have long-term sustainable funding for science in the Delta, so what does that leave? I’ll get out in front of my constituents by saying I think it leaves water users, for the large part, to make a better contribution towards the science that ultimately will affect their water supply reliability. So, when we talk about collective understanding, I hope that we not just include the agencies around this table, but also the other stakeholders that are affected by the way we manage the Delta ecosystem.”

Tim Vendlinski, Senior Policy Advisor for EPA’s Bay Delta Division, said that he would like to see the workgroup and the science program align their work with the work of the State Water Board. “When I read the flows and fishes report, I was still left with wanting to know if the science community had to make recommendations today to Felicia and the Board on what should be in the Bay Delta Water Quality Control Plan,” he said. “We haven’t done a comprehensive review in 20 years … for the salinity regime of the estuary, we have X2 as the guiding salinity, but the estuary is a different place 20 years later and there’s so much more science … how do we manage the salinity both for the beneficial uses of the fishes but also for agriculture and drinking water for the state? What are the appropriate Delta outflows? I’m still looking for that … We need to engage the scientific community now on what those outflows should be. And then temperature is a biggie. … and then there’s reservoir management …How do we optimize temperature for the cold water fishes while also protecting the supplies for drinking water and for farming? So that’s where if the scientific community could galvanize around those four areas and offer something to the board to delve into, that could be the greatest service of the scientific community.”

Tim Vendlinski, Senior Policy Advisor for EPA’s Bay Delta Division, said that he would like to see the workgroup and the science program align their work with the work of the State Water Board. “When I read the flows and fishes report, I was still left with wanting to know if the science community had to make recommendations today to Felicia and the Board on what should be in the Bay Delta Water Quality Control Plan,” he said. “We haven’t done a comprehensive review in 20 years … for the salinity regime of the estuary, we have X2 as the guiding salinity, but the estuary is a different place 20 years later and there’s so much more science … how do we manage the salinity both for the beneficial uses of the fishes but also for agriculture and drinking water for the state? What are the appropriate Delta outflows? I’m still looking for that … We need to engage the scientific community now on what those outflows should be. And then temperature is a biggie. … and then there’s reservoir management …How do we optimize temperature for the cold water fishes while also protecting the supplies for drinking water and for farming? So that’s where if the scientific community could galvanize around those four areas and offer something to the board to delve into, that could be the greatest service of the scientific community.”

Mike Chotkowski, Delta Science Coordinator with USGS, said he was uncomfortable with Tim’s suggestion that the scientific community would be recommending policy to the management agencies. “There may very well be scientists who are working for the management agencies who feel comfortable in that role, but I think at USGS, we don’t have a management mandate and we view the stewardship of the scientific process as being a pretty important issue that in some cases requires that the scientists step back from the role of recommending policy. Certainly for us, that’s the case. I think if you were to reframe your suggestion so that what you’re asking of the science community that they evaluate some potential proposed policies for their outcomes rather than recommending policy, it would be more comfortable for a lot of people.”

“Thank you for clarifying that,” responded Tim Vlendinksy. “I didn’t want to get the scientists mixed up in policy. Where I was going with that is their best professional judgment on the conditions on what is needed for the fishes. The needs assessment that if you provide these temperature regimes using these reservoirs, these are the potential outcomes, so it’s more of a scenario modeling thing than having them jump that divide into the policy realm, so they can protect their integrity.”

“I appreciate that,” replied Mr. Chotkowski. “I would suggest that those judgments regarding what the fish need are primarily judgments for the regulatory agencies. And again, I’m not suggesting that the scientific community has nothing to offer, just that what it has to offer is only science and these policy decisions are more complicated than that, so I think it’s pretty important we keep that distinction alive.”

The Committee then moved on to the next agenda item.

Delta Independent Science Board Report: Flows and Fishes in the Delta

Dr. Cliff Dahm began the agenda item by talking the function of the Delta Independent Science Board (DISB). The Delta Independent Science Board was established by the Delta Reform Act of 2009. It consists of 10 members appointed by the Delta Stewardship Council; the members have five year terms and they can serve no more than two terms. The Act requires that they be nationally and internationally prominent scientists that are able to evaluate a broad range of scientific programs that support adaptive management for the Delta, and they provide oversight of the scientific research, monitoring, and assessment programs for the Delta through periodic review. Reports from the Delta Independent Science Board are submitted to the Council, and the DISB is also consulted when the Council selects and appoints the lead scientist.

Dr. Dahm then introduced Dr. Steven Brandt, chair-elect of the DISB, who then gave a brief report on the DISB report that was issued in August of 2015, Flows and Fishes in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta: Research Needs in Support of Adaptive Management.

“The Delta Independent Science Board has a legislative responsibility to review science programs in the Delta, and we’ve chosen to do that through looking at various themes,” began Dr. Brandt. “We’ve completed a report on restoration, we’ve just completed a report on fish and flows, and our next report which has been drafted will be on adaptive management. Today I’m just going to introduce our fish and flows report which has just recently been completed.”

“Our purpose for these reviews is to identify the strategic science needs in order to improve our understanding, improve our scientific collaboration on this topic, and perhaps make the science a little bit more relevant to management needs, so our goal is to look at the science and recommend what really needs to be done in order to improve the science,” he said.

“Our purpose for these reviews is to identify the strategic science needs in order to improve our understanding, improve our scientific collaboration on this topic, and perhaps make the science a little bit more relevant to management needs, so our goal is to look at the science and recommend what really needs to be done in order to improve the science,” he said.

“Dealing with fish and flows is really a comprehensive topic,” said Dr. Brandt. “In many respects it does relate specifically to the coequal goals of water supply and ecosystem health, because fish are often viewed as an indicator of ecosystem health. So that makes both our job in reviewing our topic and looking at the science need very important and relevant to policy implications, but also it makes it very challenging.”

Dr. Brandt said they were fortunate in one respect because there has already been a lot of work done on this topic already: several scientific publications, workshops on both interior flows as well as outflows, two National Research Council reports, which all have recommendations in terms of science needs. “It was challenging because what can we do to add to that, and so we took a broad view and decided to look at it in a Delta-wide context,” he said.

The 18-month process involved interviews with agency staff, stakeholders, and academics, and asked where they felt the DISB should focus their review. The DISB then reviewed literature, attended other workshops, and had an open public comment period on the report before releasing the final document, he said.

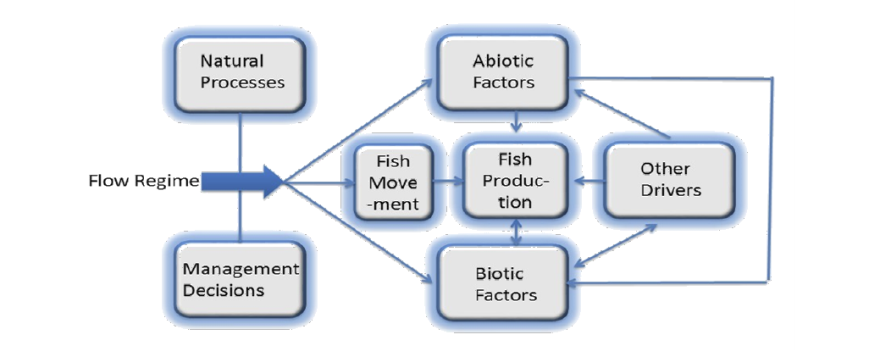

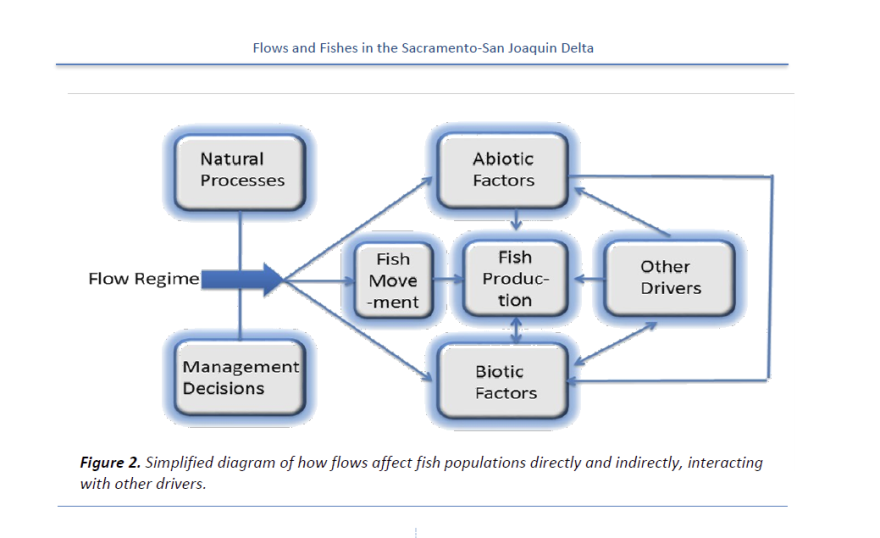

Dr. Brandt said that the general finding is that the impact of flows on fish needs to be looked at from both its direct impact and perhaps more importantly, its indirect impacts, meaning flows affecting the things that affect fish. There are clearly many agencies involved and a lot of science that has been done, much of which is statistical or correlation in nature and does suggest clearly that flows and fish and particular species of fish do have some interconnection, he said.

Dr. Brandt said that the general finding is that the impact of flows on fish needs to be looked at from both its direct impact and perhaps more importantly, its indirect impacts, meaning flows affecting the things that affect fish. There are clearly many agencies involved and a lot of science that has been done, much of which is statistical or correlation in nature and does suggest clearly that flows and fish and particular species of fish do have some interconnection, he said.

“Our overarching recommendation regarding science is that we really need to have a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms of how flows affect fishes,” he said. “The more we can understand what the mechanisms are, the better off we’ll be in terms of adaptive management, because we’ll be in a better position to clarify uncertainty and clarify risk, we’ll be able to get better expectations of outcomes when a management decision is made as to what would be the specific expectation of an outcome relative to the fish, and also it would help to strengthen and help test hypotheses.”

Dr. Brandt then summarized the report’s nine recommendations:

The first one is to focus on cause and effect and to really understand the mechanisms of the drivers of how flows affect both the indirect and the direct aspects that then affect fishes.

The second one is to expand on an integrative science approach. “Given the fact this is both clearly biological and physical and everything in between, you really need integrative in all senses of the words, integrated across agencies as well as across disciplines,” he said. “A more specific recommendation is to try and link hydrodynamic and fish models, link 3D hydrodynamic and fish models in order to get the ability to assess how a particular change or a general change in flows might affect those fishes, and we suggest a first step in this context might be having a modeling summit to actually get physical hydrodynamics people in the same room as the fish people and have them discuss what might be the appropriate time scale, space scales, what are the appropriate parameters that need to be looked at in order to answer these questions. One might even consider the development of a joint working group on this, because this might take more than one specific summit and discussions.”

The third recommendation is to link quantitative fish models with 3‐D models of water flows. Dr. Brandt then explained further about what is meant by this recommendation. “A lot of the water models are very good at measuring where water goes because that is what they are designed to do, but that makes them maybe not as good as they could be when you’re trying to assess the impacts on fish as fish have different time, space, and parameter scales,” he said.

“One example might be if you’re developing a water flow model, you’re very concerned about water density and salinity is an important component of water density,” he continued. “Temperature may not be as important, but temperature is clearly extremely important to fishes; a one degree difference in temperature is very important. When you look at the position of the X2 defined by salinity, there’s also a difference in temperature associated with that, a difference in biology, and things that fish might be more responsive to.”

“Another example of water flow is when you look at the amount of water that moves past a certain point or a rate of flow, it’s defined in usually a volume of unit time, like cubic feet per second,” he said. “That’s something fish can’t detect. Fish can detect water velocity. If you take a volume of water and move it through a floodplain, the velocity that’s important to a fish or the velocity that’s important to a sediment transport and resuspension, that is important to fish, so developing an integration of things that will affect fish at the time, space, and parameter scale and having that be done with what a 3D hydrodynamic water quality model might give us would be a significant step forward in our understanding of both the mechanisms.”

The fourth recommendation is to examine causal mechanisms on appropriate time and space scales. “We often measure fish abundance as an annual or sometimes a monthly measure of fish abundance, but the things that might be most responsive to changes in water flows might be things like growth rates which you can measure at a very fine scale. If we really want to understand what the impacts might be, let’s look at the first order affects on those fish might be.”

The fifth recommendation is to monitor vital rates of fish, things such as birth rates, death rates, and growth rates. “These are the things that you might predict might change first,” he said.

The sixth recommendation is to broaden the species focus. “There’s been a lot of focus on key and threatened species as it should be, but there’s also a lot of species that really dominate the system ecologically and some more focus ought to be spent on that,” he said.

The three other recommendations are more general: Provide timely synthesis of research and monitoring, enhance national and international connections as there are things going on in other major ecosystems that might have relevancy; and improve coordination among disciplines and institutions.

Dr. Brandt said that the Delta Independent Science Board has adopted a process for doing these reviews, one of them being to pull together a scope and then have public comment on it so they can steer the scope to relevant issues; they are also developing an outreach program to be sure reports get delivered to those who might be interested in them. The report will be in greater detail at the November Delta Stewardship Council meeting, and at their December meeting, the DISB will be having a panel discussion with agency scientists to continue discussion on this topic.

Dan Castleberry, Assistant Regional Director at US Fish and Wildlife Service, notes some of those sitting around the table have been working on these issues for a long time: “Do you see a timeline where some of these concepts are likely to come to fruition? The linking quantitative fish models with 3D models, one example. We have for some time been collecting information on vital rates in fishes, but we’ve struggled with making that mechanistic connection. From your experience elsewhere, where do you see these kinds of things coming to fruition in a system like this?”

Dan Castleberry, Assistant Regional Director at US Fish and Wildlife Service, notes some of those sitting around the table have been working on these issues for a long time: “Do you see a timeline where some of these concepts are likely to come to fruition? The linking quantitative fish models with 3D models, one example. We have for some time been collecting information on vital rates in fishes, but we’ve struggled with making that mechanistic connection. From your experience elsewhere, where do you see these kinds of things coming to fruition in a system like this?”

“In the Chesapeake Bay which I’m very familiar with, there was a lot of effort to develop a 3D water model and a 3D hydrodynamic water quality model, and we tried to then link it to a fish, and we eventually did it through a decoupled system,” said Dr. Brandt. “Take the data out from here and put it into the fish and it was because the scales were quite different; there were at 23 parameters coming out every 6 minutes and they had temperature at 1.2 degree intervals for some density argument. That makes it much more difficult to do that. I know there’s been some very successful stuff done like that in the Delta right now where taking some of those model outputs and looking at smelt, for example, and making predictions of temperature and putting them in the salmon models, so I think some serious progress has been made. I think going back to getting folks together and saying what can we do with existing models to tweak them a bit to look at them from a fish perspective and see if the right parameters can be generated from that or can they be tweaked or modified.”

“What we would recommend is to have an open source model as those things give the opportunity for people to dive in and use an accepted two or three models,” Dr. Brandt continued. “This has been done in the fish world. In the fish world, bioenenergetics is pretty standard. It’s mass balance, what they eat, they either grow or it goes to waste or use, and the same model can be applied to thousands of different species as long as you have the specific parameter for that individual fish, and I think linking that generic model to some sort of generic fish-centric output model from a hydrodynamic, I think in a year or two, you could have very significant step increases.”

Chuck Bonham, Director of the Department of Fish and Wildlife, asked, “If you conclude a leading recommendation is to develop a deeper mechanistic understanding, so causation not correlation, then is the linkage of the models the primary strategy to achieve that mechanistic understanding?”

Chuck Bonham, Director of the Department of Fish and Wildlife, asked, “If you conclude a leading recommendation is to develop a deeper mechanistic understanding, so causation not correlation, then is the linkage of the models the primary strategy to achieve that mechanistic understanding?”

“It’s certainly one of the mechanisms,” responded Dr. Brandt. “It’s a matter that the models can help generate good information on where the data gaps are, but can also help test hypotheses. I think it is a major step forward because you need to put the mechanisms into some sort of context … There’s a lot of data out there, and developing a model might allow one to test some of those different pathways to find out which ones may or may not have any validity or have lesser validity than the other ones. And then that can help to define where more intense monitoring needs to be done or where more specific science needs to be done.”

“Can you think of a non-model based way to test a mechanistic understanding in a system where it’s hard to control the movement of water for analyzing a hypothesis?,” asked Mr. Bonham.

“There are a lot of field studies,” said Dr. Brandt. “If you look at flows impact on movement, the actual flow itself in terms of passive transport or active migrations and so forth, there are clearly experiments that are underway and can be done in terms of acoustic tagging or possibly some active acoustics to see whether or not those flows are actually changing movements of that particular species and that’s an experiment that’s probably more simpler to do. You can also look at things related to temperature and growth, but linking it to models is probably one of the fundamental ways to try and understand the underlying mechanisms that’s driving it.”

“Let me endorse your recommendation on examining causal mechanisms as I think that’s extremely important in this conversation,” said Mark Cowin, Director of Water Resources. “I think the title of the report is bit off-putting. Maybe it’s a better set in context regarding our goals for ecosystem restoration and sustaining important fish populations, but if we’re going to have a productive conversation among the broader set of interests that are interested in the topics here today, we’ve got to be able to set the context and people believe the context is in looking at the broader suite of stressors that are affecting the ecosystem in equal proportion. So a focus on flows and fish – I don’t mean to diminish that important mechanism and the work that needs to be done to better understand that, but I just feel like we’ve got to find a better way of setting the stage for that part of the conversation in the broader science agenda that addresses all of the stressors that are affecting fish populations.”

“Let me endorse your recommendation on examining causal mechanisms as I think that’s extremely important in this conversation,” said Mark Cowin, Director of Water Resources. “I think the title of the report is bit off-putting. Maybe it’s a better set in context regarding our goals for ecosystem restoration and sustaining important fish populations, but if we’re going to have a productive conversation among the broader set of interests that are interested in the topics here today, we’ve got to be able to set the context and people believe the context is in looking at the broader suite of stressors that are affecting the ecosystem in equal proportion. So a focus on flows and fish – I don’t mean to diminish that important mechanism and the work that needs to be done to better understand that, but I just feel like we’ve got to find a better way of setting the stage for that part of the conversation in the broader science agenda that addresses all of the stressors that are affecting fish populations.”

The topic of fish and flows is one we’ve heard many times, said Dr. Brandt. “Within the text, we do give a lot of weight to the alternative drivers. We’ve listed drivers in our various diagrams as being there.”

“Having sat through days of hearings on our SED, I saw more arguments about correlations from the same charts that came to different results, so anything that you could do that could get us beyond correlation, whether 3D or mechanistic or otherwise, would be welcome just to be able to sort out what’s important and what’s not,” said State Water Board Chair Felicia Marcus. “One thing I’m always a little nervous amount is a question of time. I recognize that was a good caution about scientists giving us management policy makers data but not necessarily making recommendations but I also tend to sometimes be a little impatient perhaps to try and figure out whether we can come up with really useful information that can help us sort out the stressor issue without having folks opportunistically say, see this proves that flows don’t matter at all. On both ends of the spectrum, I think flows end up being misused in the absence of something else that people can point to, but how fast do you think any of these things could happen in a way that would be useful in a neutral way for illuminating what the issues may well be … It’s not like you can get in the mind of the fish. It’s tantalizing in thinking things that do seem obvious about what fish can sense versus the data we have, so I’m very intrigued, but what kind of time scale are we talking on some of these?”

“Having sat through days of hearings on our SED, I saw more arguments about correlations from the same charts that came to different results, so anything that you could do that could get us beyond correlation, whether 3D or mechanistic or otherwise, would be welcome just to be able to sort out what’s important and what’s not,” said State Water Board Chair Felicia Marcus. “One thing I’m always a little nervous amount is a question of time. I recognize that was a good caution about scientists giving us management policy makers data but not necessarily making recommendations but I also tend to sometimes be a little impatient perhaps to try and figure out whether we can come up with really useful information that can help us sort out the stressor issue without having folks opportunistically say, see this proves that flows don’t matter at all. On both ends of the spectrum, I think flows end up being misused in the absence of something else that people can point to, but how fast do you think any of these things could happen in a way that would be useful in a neutral way for illuminating what the issues may well be … It’s not like you can get in the mind of the fish. It’s tantalizing in thinking things that do seem obvious about what fish can sense versus the data we have, so I’m very intrigued, but what kind of time scale are we talking on some of these?”

“Just take the recommendation of a 3D hydrodynamic model connected to a fish model,” said Dr. Brandt. “That model can be driven by a number of different processes, anything from climate change to nutrient loading and so forth. The discussion was about a couple of years. If you got the right people together in the right room, and put together existing information and tweaked it in the right way, and that may be, it’s always related to time versus money, if you threw a lot of money at it, you could get it done a lot shorter.”

For more information …

- Click here to download a copy of the report, Flows and Fishes in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta: Research Needs in Support of Adaptive Management

- For the meeting agenda and materials for the November 2015 meeting of the Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee, click here. This is agenda items #3 and #5.

- To watch the webcast, click here.

- For part 1 of coverage from this meeting, go here: Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee, pt 1: Delta Challenges: Complex, Chaotic or Simply Cantankerous

- For part 2 of coverage from this meeting, go here: Delta Plan Interagency Implementation Committee, Pt 2: An update on California Eco Restore and the Yolo Bypass

Help Maven bridge the funding gap!

Help Maven bridge the funding gap!

Your help is needed for Maven’s Notebook to continue operations in 2016.