The regulation will address required components of groundwater sustainability plans and how those plans will be evaluated

With the first set of regulations now completed, staff at the Department of Water Resources Sustainable Groundwater Management Program are well underway with development of the second set of regulations which are due by June 1st of 2016.

With the first set of regulations now completed, staff at the Department of Water Resources Sustainable Groundwater Management Program are well underway with development of the second set of regulations which are due by June 1st of 2016.

At the November meeting of the California Water Commission, Senior Engineering Geologist Trevor Joseph briefed commission members on the Department’s progress on crafting the regulations, including the major components of the regulations and some of the comments from stakeholders received so far.

Trevor Joseph began by presenting a timeline of the major milestones in California groundwater policy. “Pre-SGMA, groundwater management was a voluntary activity that typically occurred within service area boundaries, often water districts, and did not cover the entire basin or basins, although in some cases it did,” he said. “Prior to SGMA, there was minimal implementation of groundwater management planning, although there are many great groundwater management plans and efforts that occurred. Now, post SGMA, groundwater management must be completed through these new groundwater sustainability plans or what are called alternatives, or adjudications. It’s now required that these plans be implemented and now there’s the state backstop, the State Water Resources Control Board.”

Trevor Joseph began by presenting a timeline of the major milestones in California groundwater policy. “Pre-SGMA, groundwater management was a voluntary activity that typically occurred within service area boundaries, often water districts, and did not cover the entire basin or basins, although in some cases it did,” he said. “Prior to SGMA, there was minimal implementation of groundwater management planning, although there are many great groundwater management plans and efforts that occurred. Now, post SGMA, groundwater management must be completed through these new groundwater sustainability plans or what are called alternatives, or adjudications. It’s now required that these plans be implemented and now there’s the state backstop, the State Water Resources Control Board.”

Mr. Joseph noted that SGMA technically applies to all 515 groundwater basins and subbasins in California, but it is the 127 high and medium priority basins that are required to address and develop groundwater sustainability plans, alternatives to these plans, or adjudications. Those 127 represent 96% of the average annual groundwater supply over the basins, and 88% of the population over groundwater basins in California.

Mr. Joseph noted that SGMA technically applies to all 515 groundwater basins and subbasins in California, but it is the 127 high and medium priority basins that are required to address and develop groundwater sustainability plans, alternatives to these plans, or adjudications. Those 127 represent 96% of the average annual groundwater supply over the basins, and 88% of the population over groundwater basins in California.

SGMA identifies the roles and responsibilities for three main entities: DWR is developing and implementing regulations and providing technical assistance; Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) are required to prepare and implement a groundwater sustainability plans or these alternatives, and the State Board is the enforcement entity to intervene when GSAs are unsuccessful.

SGMA identifies the roles and responsibilities for three main entities: DWR is developing and implementing regulations and providing technical assistance; Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) are required to prepare and implement a groundwater sustainability plans or these alternatives, and the State Board is the enforcement entity to intervene when GSAs are unsuccessful.

He presented a timeline for implementation, noting that the GSP regulations are due June 1st of 2016, alternatives to GSPs are due January 1st, 2017, and groundwater sustainability plans are due either 2020 or 2022.

He presented a timeline for implementation, noting that the GSP regulations are due June 1st of 2016, alternatives to GSPs are due January 1st, 2017, and groundwater sustainability plans are due either 2020 or 2022.

SGMA identifies a series of required components of the regulations, such as required plan components, additional plan elements, coordination, and other information that will assist local agencies in developing and implementing GSPs and the coordination agreements. This set of regulations will detail the requirements for evaluation and implementation of groundwater sustainability plans.

Mr. Joseph pointed out that SGMA’s chapter 7 lists best management practices and technical assistance, but there’s really no description in terms of prescriptive requirements that the Department needs to follow in terms of the content. “There are public meetings associated with those, but we like to think of the regulations perhaps as the minimum requirements and best management practices as guidance for implementing SGMA for local agencies and GSAs,” he said.

He then presented a slide showing the differences between GSPs and alternatives that are applicable to the 127 high and medium basins or subbasins. GSPs and alternatives need to cover the entire basin or subbasin; he noted that it can be a single GSP that covers the entire basin or a multiple GSAs that have a coordination agreement.

He then presented a slide showing the differences between GSPs and alternatives that are applicable to the 127 high and medium basins or subbasins. GSPs and alternatives need to cover the entire basin or subbasin; he noted that it can be a single GSP that covers the entire basin or a multiple GSAs that have a coordination agreement.

GSPs must be submitted by a GSA, whereas alternatives can be submitted by either a GSA or a local agency. GSPs must be completed by 2020 for basins designated as critically overdrafted, and 2022 for high and medium priority basins. GSPs have annual reporting requirements and five year evaluations as do alternatives. Alternatives are due by January 1st, 2017; there are also eligibility requirements for the alternatives, so it’s a different mechanism to meet SGMA.

There are three options for forming GSAs and developing GSPs, he said. “You can have one GSA that completes one GSP for the entire basin or subbasin, you can have multiple GSAs that complete one GSP for the entire basin or subbasin, or you can have many GSAs that complete many GSPs with a coordination agreement,” he said. “It will be interesting to see what collection we ultimately get. I think there’s maybe some advantages to coordinating and trying to complete one GSP, but the act certainly allows for multiple GSPs if they are coordinated.”

There are three options for forming GSAs and developing GSPs, he said. “You can have one GSA that completes one GSP for the entire basin or subbasin, you can have multiple GSAs that complete one GSP for the entire basin or subbasin, or you can have many GSAs that complete many GSPs with a coordination agreement,” he said. “It will be interesting to see what collection we ultimately get. I think there’s maybe some advantages to coordinating and trying to complete one GSP, but the act certainly allows for multiple GSPs if they are coordinated.”

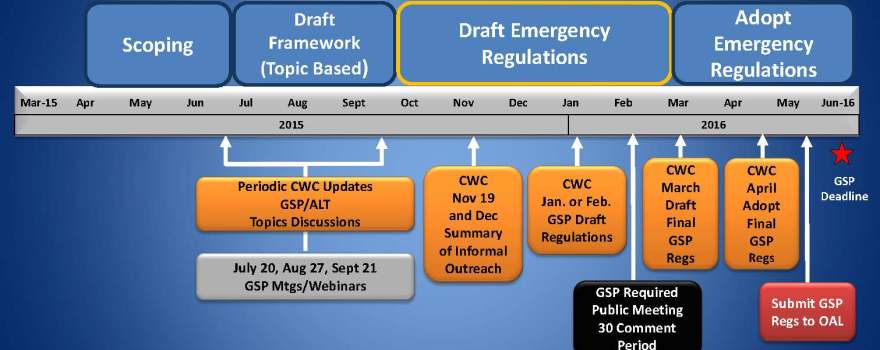

Mr. Joseph said they are following a four phase process, similar to the process for the basin boundary regulations. They have completed the first phase, scoping, and over the summer they completed the second phase, the draft framework. They are now drafting the emergency regulation phase and plan to have draft emergency regulations out by the January timeframe, working towards adopting the regulations by June 1st, 2016.

Mr. Joseph said they are following a four phase process, similar to the process for the basin boundary regulations. They have completed the first phase, scoping, and over the summer they completed the second phase, the draft framework. They are now drafting the emergency regulation phase and plan to have draft emergency regulations out by the January timeframe, working towards adopting the regulations by June 1st, 2016.

To gather stakeholder effort, they identified a series of topics and drafted discussion papers to help focus the discussion. They then discussing them in three batches with advisory groups and stakeholders, as well as the public in a series of meetings held during the summer months. All totaled, 40 meetings and over 100 hours were spent gathering input through public meetings and meetings with advisory committees and stakeholder groups. He noted that the topics don’t necessarily represent everything that was discussed; there were other topics discussed such as stakeholder involvement, that weren’t identified as a separate topic.

To gather stakeholder effort, they identified a series of topics and drafted discussion papers to help focus the discussion. They then discussing them in three batches with advisory groups and stakeholders, as well as the public in a series of meetings held during the summer months. All totaled, 40 meetings and over 100 hours were spent gathering input through public meetings and meetings with advisory committees and stakeholder groups. He noted that the topics don’t necessarily represent everything that was discussed; there were other topics discussed such as stakeholder involvement, that weren’t identified as a separate topic.

He presented a slide of the main components of the regulation, noting that they are now currently drafting the emergency regulations. He then discussed each component in more detail along with a sampling of the stakeholder comments they received.

He presented a slide of the main components of the regulation, noting that they are now currently drafting the emergency regulations. He then discussed each component in more detail along with a sampling of the stakeholder comments they received.

Governance and coordination

The first component is governance, coordination, and land use. “It’s hard to talk about governance without talking about chapters that are not related to GSPs directly,” said Mr. Joseph. “The groundwater sustainability requirements are in SGMA’s Chapter 6; Chapter 4 is the GSA formation requirements. GSAs must be formed by June 30, 2017. SB 13 changed this a little bit; now we’re going to be reviewing those GSA notifications. I bring this up because in chapter 4, there’s a requirement that local agencies consider the interests of all beneficial uses and users of groundwater, and it lists a series of entities. It’s going to be important that that’s looked at closely as it relates to preparing a plan in Chapter 6.”

The first component is governance, coordination, and land use. “It’s hard to talk about governance without talking about chapters that are not related to GSPs directly,” said Mr. Joseph. “The groundwater sustainability requirements are in SGMA’s Chapter 6; Chapter 4 is the GSA formation requirements. GSAs must be formed by June 30, 2017. SB 13 changed this a little bit; now we’re going to be reviewing those GSA notifications. I bring this up because in chapter 4, there’s a requirement that local agencies consider the interests of all beneficial uses and users of groundwater, and it lists a series of entities. It’s going to be important that that’s looked at closely as it relates to preparing a plan in Chapter 6.”

SGMA’s Chapter 6 requires a public hearing prior to the adoption or amendment of a groundwater sustainability plan. The GSA shall also review and consider comments from cities and counties, and consult with cities and counties that request consultation as part of that adoption or amendment.

The public notification of participation and the advisory committee section are two components. “Prior to the initiation of and development of a GSP, the GSA shall make available to the public and to DWR a written statement of in which interested parties may participate in the development and implementation of the GSP,” he said. “That’s very important as it relates to Chapter 4, as identifying those interests and involving them early is called out in the act. And then the GSA may appoint and consult with an advisory committee.”

He then reviewed some of the stakeholder comments received so far. “It was suggested that a communications plan that provides a schedule and major milestones for actions, roles and responsibilities be included,” he said. “A lot of comments related to stakeholders said they should have equal voice in GSP development and implementation, while other stakeholders felt that it should be limited to the existing SGMA requirements. So there are folks who have very different interpretation or interests in terms of how stakeholders should be involved.”

With respect to coordination, there are two types: intrabasin coordination which refers to multiple GSAs completing multiple GSPs, shown in the left diagram. There are a series of requirements related to data and methodology called out in SGMA, such as groundwater elevation data, groundwater extraction data, and sustainable yield that are more prescriptive in terms of what needs to be coordinated, he said.

With respect to coordination, there are two types: intrabasin coordination which refers to multiple GSAs completing multiple GSPs, shown in the left diagram. There are a series of requirements related to data and methodology called out in SGMA, such as groundwater elevation data, groundwater extraction data, and sustainable yield that are more prescriptive in terms of what needs to be coordinated, he said.

As for stakeholder comments, the reference to using same data and methodologies has received a lot of interest, he said. “Some feel that same should be exactly the same – every data and methodology, and the technical items such as water budget, how they approach that,” he said. “Modeling is a good example; if there’s multiple models in a basin, some stakeholders say they should have to conform and have the same model. Other stakeholders fell that that is problematic; they’ve spent millions of dollars developing these models, maybe it’s a huge basin, maybe they are already managing the groundwater sustainably and to force them to come to develop one model may not be in the spirit of the act, and as long as the input parameters in the model are the same, then that’s the intent. Other examples of same might be groundwater elevation data collection where the timing and the way that they approach that is pretty important so that basin wide contour maps and analysis can be developed, so there has been a lot of discussion around this.”

Interbasin coordination is not a term explicitly called out in the act, but there is a provision that the Department has to evaluate whether or not one basin affects the ability of another basin to reach sustainable groundwater management, he said. “Why that’s important is that there are basins that are hydrologically connected, meaning groundwater flows beneath these basin boundaries, and so there’s a lot of stakeholder support for some sort of communication in the regulations as it relates to this other type of coordination.”

Interbasin coordination is not a term explicitly called out in the act, but there is a provision that the Department has to evaluate whether or not one basin affects the ability of another basin to reach sustainable groundwater management, he said. “Why that’s important is that there are basins that are hydrologically connected, meaning groundwater flows beneath these basin boundaries, and so there’s a lot of stakeholder support for some sort of communication in the regulations as it relates to this other type of coordination.”

Determining whether or not a basin adversely affects an adjacent basin is going to be extremely challenging, Mr. Joseph said. “One of – if not the most challenging aspects of SGMA is interbasin coordination, because one basin may be operating water levels lower than another and be feeding that basin, and if they change the approach to that, it will affect the other one.”

“Some stakeholders feel we should use the exact same requirements as intrabasin coordination, that essentially from a scientific perspective, it’s the same – there’s water moving under these basin boundaries. Others said don’t use that exact same and it should be more just a general agreement of the water flows. So there are a lot of comments that vary significantly on what the requirements should be. This is not explicitly described in the act in terms of prescriptive requirements, so this is very much about what DWR is going to need to evaluate whether or not one adversely impacts another.”

Land use is another very important component, and there are a series of sections that are relevant. “One is a government code section that requires that before the adoption or amendment of the city or county’s general plan, the planning agency shall evaluate and consider the GSP,” he said.

Land use is another very important component, and there are a series of sections that are relevant. “One is a government code section that requires that before the adoption or amendment of the city or county’s general plan, the planning agency shall evaluate and consider the GSP,” he said.

SGMA and the water code requires consideration of all beneficial uses and users of water, and land use agencies are one of those agencies that are explicitly listed in that section, he said. “The GSP must contain a description of consideration of county and general plans and how these GSPs may affect general plans, so in some ways, the government code is more about the counties and cities looking at the GSPs, and the other one, a little bit more interpretive perhaps, is that the GSAs working with the counties to look at the general plans.”

“For the stakeholder comments, they said GSPs should describe how land use and planning agencies were engaged, counties and cities should be signatory to all GSAs, and GSAs should provide technical information and format for ease of use in planning decisions,” he said. “Generally there’s a lot of concern about the reality of implementing SGMA without land use agencies being involved. GSAs should recommend protection of recharge areas to local land use and planning agencies, again, a lot of comments here.”

Basin conditions

Basin conditions are another very important component, he said. SGMA requires collection of data regarding the physical characteristics in the aquifer system, historic data especially data related to the undesirable results, maps and boundaries, maps of recharge areas, and where the appropriate planning agencies reside.

Basin conditions are another very important component, he said. SGMA requires collection of data regarding the physical characteristics in the aquifer system, historic data especially data related to the undesirable results, maps and boundaries, maps of recharge areas, and where the appropriate planning agencies reside.

“You can think of this component really as the fundamental component for building planning; this is the state of the basin in which now, if its articulated clearly, that the agencies then will use as the basis for setting future measurable objectives and interim milestones, so it’s an important component.”

Sustainability Goal

“The terms, sustainability goals, sustainable groundwater management, and sustainable yield provide a framework to measure outcomes as it relates to the undesirable results,” he said. “Those undesirable results are surface water depletion, reduction of storage, degraded water quality, seawater intrusion, land subsidence and lowering of groundwater levels. And they are undesirable when they exceed significant and unreasonable levels, so the term sustainability goals, sustainable groundwater management, and sustainable yield are fairly well defined in the act, but the definition of what’s significant and unreasonable is not defined.”

“The terms, sustainability goals, sustainable groundwater management, and sustainable yield provide a framework to measure outcomes as it relates to the undesirable results,” he said. “Those undesirable results are surface water depletion, reduction of storage, degraded water quality, seawater intrusion, land subsidence and lowering of groundwater levels. And they are undesirable when they exceed significant and unreasonable levels, so the term sustainability goals, sustainable groundwater management, and sustainable yield are fairly well defined in the act, but the definition of what’s significant and unreasonable is not defined.”

“Another way to look at them is using this graphic,” he said. “To reach a sustainability goal, you need to be high on this conceptual sustainability y axis, and you need to have relatively low uncertainty on the x axis, and the sustainability goal here is shown in this blue fog of whatever sustainability is, but what it is it’s operating within your sustainable yield and avoiding those undesirable results at significant reasonable levels.”

“Another way to look at them is using this graphic,” he said. “To reach a sustainability goal, you need to be high on this conceptual sustainability y axis, and you need to have relatively low uncertainty on the x axis, and the sustainability goal here is shown in this blue fog of whatever sustainability is, but what it is it’s operating within your sustainable yield and avoiding those undesirable results at significant reasonable levels.”

“The example here shows GSA 1 who currently is not meeting their sustainability goal. They have some work to do. They either need to collect some data to drive down uncertainty and/or they need to develop and implement projects to increase yield or address the undesirable results,” he said. “GSA 2, they are already there. Maybe an alternative would work for GSA 2 in this example where there, it’s about optimization. They are already avoiding significant unreasonable levels and they are meeting their sustainability goals.”

“We feel that these terms are interrelated,” he said. “Sustainability goal leads to sustainable groundwater management which leads to a sustainable yield,” he said. “I like to think of it in a reverse order – that if you’re addressing significant unreasonable levels as it relates to these undesirable results, than you’re operating to a sustainable yield likely, you’re doing sustainable groundwater management and you’re achieving your groundwater sustainability goals, so that’s why it’s so important in our perspective to look at these undesirable results as really the metric and the outcome for sustainability.”

Measurable objectives and undesirable results

SGMA specifies that all GSPs shall include measurable objectives and interim milestones in increments of 5 years to achieve the sustainability goal, which must be met within 20 years of implementation. “The comments that we’ve received is that the measurable objectives and interim milestones should be specific and quantifiable; tied to discrete numerical values; contain thresholds, triggers, and actions; be adaptive, meaning allowed to change; and then we should provide some clear guideline as it relates to measurable objectives, again in that situation where there is interbasin coordination, or flow between basins.”

SGMA specifies that all GSPs shall include measurable objectives and interim milestones in increments of 5 years to achieve the sustainability goal, which must be met within 20 years of implementation. “The comments that we’ve received is that the measurable objectives and interim milestones should be specific and quantifiable; tied to discrete numerical values; contain thresholds, triggers, and actions; be adaptive, meaning allowed to change; and then we should provide some clear guideline as it relates to measurable objectives, again in that situation where there is interbasin coordination, or flow between basins.”

“I think the key here for a lot of stakeholders was that it shouldn’t be ambiguous,” he said. “Interim milestones shouldn’t be poorly defined or uncertain because then how will the GSAs know whether or not they are reaching sustainable groundwater management and the sustainability goal and how will then we assess their progress towards meeting that goal.”

Mr. Joseph then presented a conceptual slide for interim milestones, noting that sustainability is on the y axis and time is on the x axis.

Mr. Joseph then presented a conceptual slide for interim milestones, noting that sustainability is on the y axis and time is on the x axis.

“This might be GSA 1 where they are working on towards meeting their sustainability goal, and they have a projected path to get there, a series of projects, data collection,” he said. “There’s uncertainty, and at the interim milestones every 5 years, we’re doing evaluation to see if they are reaching progress with their sustainability goal. In this example, interim milestone 2, they’ve exceeded the band of uncertainty, they are not on track, and they probably need to do some corrective actions to get back on track so they are realigning with their projected path towards reaching that goal.”

SGMA defines undesirable results as chronic lowering of groundwater levels indicating a depletion of supply, reduction of groundwater storage, seawater intrusion, degraded water quality, land subsidence that substantially interferes with surface land uses, and depletions of interconnected surface water that adversely impact beneficial uses of the surface water.

Some of the stakeholder comments were that ‘significant and unreasonable’ should largely be based on site specific considerations that are defined and developed at the local level; some said the state should develop minimum standard or framework for each undesirable result, and that should be established regardless of site specific conditions, Mr. Joseph said.

“Now I think you can have both, but it’s a real trick in regulations to write that up,” he said. “I think there was a lot of understanding that developing quantitative minimum standards for undesirable results where there is no state standard (and the only ones that there are some state standards for water quality and sea water intrusion) but given the time that’s allowed to develop quantified minimum standards statewide was not achievable, so we feel that the framework is probably the more appropriate way to handle defining what is significant and unreasonable. This one we’re spending a lot of time and it’s one of the most important components because this drives all those other metrics.”

The ‘SGMA accountability date’ is a term that DWR is coining, Mr. Joseph said. “It’s not actually stated in the act but in our mind, it encapsulates this provision in SGMA: ‘That the GSP may but is not required to address undesirable results that occur before January 1, 2015,’” he said. “Why this is important, especially early in the dialog, is that a lot of stakeholders interpreted this as a snapshot in time. Wherever undesirable result levels were or rates were as of January 1, 2015, that’s the level or the rate that they need to be managed to.”

The ‘SGMA accountability date’ is a term that DWR is coining, Mr. Joseph said. “It’s not actually stated in the act but in our mind, it encapsulates this provision in SGMA: ‘That the GSP may but is not required to address undesirable results that occur before January 1, 2015,’” he said. “Why this is important, especially early in the dialog, is that a lot of stakeholders interpreted this as a snapshot in time. Wherever undesirable result levels were or rates were as of January 1, 2015, that’s the level or the rate that they need to be managed to.”

“We think it’s not that clear and it’s not that obvious, and why I say that maybe can be extrapolated from these stakeholder comments: That GSP regulations should provide flexibility for GSAs to manage undesirable results below levels observed at the SGMA accountability date if they are not significant and unreasonable,” he continued. “Examples include basins where maybe as of that date, January 1, 2015, water levels were 5 feet below ground surface, and they want to exercise the basin for conjunctive use or just use that storage, that they should be held to hold it at that 5 foot below ground surface elevation if it’s truly not significant and unreasonable if it were lower.”

“The same could be said though, in some cases undesirable results will continue based on prior actions that should be addressed as a requirement in GSP regulations,” he said. “An example here is seawater intrusion or subsidence; if seawater intrusion is moving inland or subsidence is at a significant and unreasonable rate or level, just because it was at that rate January 1st, 2015, doesn’t mean that that rate or level should continue. It may be significant and unreasonable and needs to be addressed, so again there was some confusion on this, but it really comes down to what’s significant and unreasonable in the basin.”

Monitoring plan

SGMA sets a number of requirements for monitoring with respect to existing monitoring sites (identification of data gaps), types of measurements, frequency of monitoring, and monitoring protocols.

SGMA sets a number of requirements for monitoring with respect to existing monitoring sites (identification of data gaps), types of measurements, frequency of monitoring, and monitoring protocols.

“Here the comments ranged from appropriate spatial and temporal resolution is important, which makes sense,” he said. “Resolution should vary but be tied to site-specific conditions, and there were suggestions that the monitoring frequency should be monthly, some said annually, and some quarterly, so comments vary. And that water budget information should be a requirement.”

Implementation and reporting

SGMA lists several annual reporting requirements: groundwater elevations, annual aggregated groundwater extraction, surface water supply used for groundwater recharge, total water used, and change in groundwater storage. “Stakeholder comments were that standardized approaches are needed but shouldn’t be prescriptive, that the units and metadata should be a requirement, and transparency of data is going to be important,” he said.

SGMA lists several annual reporting requirements: groundwater elevations, annual aggregated groundwater extraction, surface water supply used for groundwater recharge, total water used, and change in groundwater storage. “Stakeholder comments were that standardized approaches are needed but shouldn’t be prescriptive, that the units and metadata should be a requirement, and transparency of data is going to be important,” he said.

With respect to implementation, SGMA requires DWR to review and assess these plans every 5 years to identify corrective actions and address deficiencies in these plans, and GSAs are required to periodically evaluate whether or not their GSPs are effective. “Stakeholder comments here were that DWR should allow for GSA consultation prior to State Board involvement and that we shouldn’t automatically stamp a plan or implementation inadequate, meaning subject to State Board intervention. There should be some process established so that GSA can either explain that DWR got the evaluation wrong, or address deficiencies in the plan or implementation.”

“Adaptive management is necessary and should not just every five years but should be a lot more frequently; some stakeholders said not formalized, but although the term adaptive management is not used in SGMA, the adaptive management concept is something that’s addressed in SGMA.”

Alternative plans

There are three options for alternative plans: Potentially an existing groundwater management plan or other law authorizing groundwater management, an adjudicated action, or an analysis that the basin is operated within a sustainable yield for a period of ten years. “These are three options that local agencies can take as opposed to preparing a groundwater sustainability plan,” he said.

There are three options for alternative plans: Potentially an existing groundwater management plan or other law authorizing groundwater management, an adjudicated action, or an analysis that the basin is operated within a sustainable yield for a period of ten years. “These are three options that local agencies can take as opposed to preparing a groundwater sustainability plan,” he said.

“Stakeholder comments were that the alternative must cover the entire basin and that’s our interpretation of the code, while other stakeholders felt that it shouldn’t cover the entire basin; that alternatives should be fraction of the basin,” he said. “I can see that perspective especially as it relates to existing groundwater management plans. A lot of groundwater management plans don’t cover the entire basin. However, it was identified by stakeholders that there’s a lot of difficulties and it’s kind of an apples and oranges between alternatives and regular GSPs in the same basin or subbasin. … It’s a very mixed bag of differences.”

“The alternatives in large part are likely for entities that are already managing the basin sustainably,” Mr. Joseph continued. “We feel looking at prior groundwater management planning efforts that there’s probably not a lot that will be able to meet the alternative requirement. There are great groundwater management plans out there, but again if they don’t cover the entire basin or subbasin, and haven’t been implemented to the technical requirements in GSP regulations and can show sustainability, then they may not be eligible in this option. We don’t feel that an alternative will be an option for many and that most basin managers and GSAs will likely have to do GSP. We’ve also heard from stakeholders that the the technical adequacy of an alternative needs to be likely equally to a GSP.”

Fringe areas are not defined in the act, but the term is one DWR has coined to describe areas outside of an adjudication, Mr. Joseph said. “In many cases an adjudication covers the vast majority of the basin or subbasin, but there may be these little small areas that are not covered within the adjudication. Stakeholders have asked about the approaches that are required as it relates to GSP regs for these areas. Do we have to prepare a GSA, do we have to complete a GSP?”

Fringe areas are not defined in the act, but the term is one DWR has coined to describe areas outside of an adjudication, Mr. Joseph said. “In many cases an adjudication covers the vast majority of the basin or subbasin, but there may be these little small areas that are not covered within the adjudication. Stakeholders have asked about the approaches that are required as it relates to GSP regs for these areas. Do we have to prepare a GSA, do we have to complete a GSP?”

“The county is often the only eligible entity or local agency that could possibly become a GSA in many cases in these areas,” he said. “The comments we received is that the fringe areas should be allowed to conform to a lesser GSP standard, especially if the adjudication is already addressing groundwater management efforts as designed, or the fringe areas are perhaps already being sustainably managed, or have little or no groundwater use, and so there’s a lot of comments that it should be a lesser standard. Others have said fringe areas should not be allowed to conform to a lesser standard – that there is still the opportunity for groundwater to be used in these areas, although the County would have land use authority and could possibly control that, but that they should conform to the exact same standards as a GSP.”

Mr. Joseph said that they have also heard from some county officials that they are not equipped to manage groundwater. “They historically haven’t managed groundwater in these fringe areas, it hasn’t been an issue, and the adjudication is widely understood as the management entity, certainly not in the fringe areas but in the basin, so they are really scrambling to determine how to approach this issue.”

“For my benefit to be clear, the ‘fringe area’ is really applicable only if you have an adjudication or a special act district, otherwise they are white areas that the counties do have a responsibility to manage in a nonadjudicated or special act managed area,” clarifies Commissioner Orth.

Mr. Joseph concurred. “We’re defining fringe areas as areas around adjudications. And frankly this is one issue that’s taking a lot of time and energy to think through and discuss. It’s likely not one of the pivotal areas that will lead us not to sustainable management statewide, but it’s one of the complexities of putting together regs is thinking about all the requirements statewide in all these situations.”

In closing …

Mr. Joseph concluded by saying he would like to return next month to give more details on how they are planning to approach these different components of the regulations.

“And with that … “

For more information …

- Click here for the agenda, meeting materials, and webcast for the November meeting of the California Water Commission. This is agenda item 7.

- DWR Sustainable Groundwater Management website

- DWR GSP Emergency Regulation Website

Related content …

Help Maven bridge the funding gap!

Help Maven bridge the funding gap!

Your help is needed for Maven’s Notebook to continue operations in 2016.