Dr. Mark Lubell shares his research which is geared at understanding the nature of institutional connectivity and interactions governing the socially and ecologically complex Bay Delta system

Dr. Mark Lubell is a professor in the Department of Environmental Science and Policy at UC Davis, as well as Director of the Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior. In the Brown Bag seminar held earlier this year, he explained how social-ecological systems are governed by complex interactions among multiple actors, policy institutions, and issues, relating this to research he has conducted in the Bay Area and in the Delta.

Dr. Mark Lubell began by explaining what he does as an environmental social scientist. “I’m actually a political scientist by training,” he said. “Half of my identity is disciplinary and the other half is more inter-disciplinary because I’m really interested in human behavior and cooperation problems and how those issues play out in the context of governance and other environmental problems.”

“I take a quantitative approach very often that tries to understand why people are making the decision they do in the context of governance systems and in the context of the cooperation problems that are there,” he continued. “I study not only water governance, but I also study for example farmer behavior with respect to sustainability issues and climate change and similar, so the term, ‘environmental social scientist’ is sort of a term that’s evolved; you’ll find some graduate programs in environmental social science now that try to take anything that’s useful from any discipline of social science to try to understand some of these issues.”

This is the type of work in water and other issues being done at the Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior by the faculty and graduate students. “The Water Management and Complex Governance Systems project includes some of the world’s best network scientists because we do use network science and analysis as a big part of the methodological toolkit in this,” he said. “We network with people from all over the world, such as Argentina, Australia, and other parts of the US that are doing similar studies in other estuarine systems like the Delta, or any sort of social-ecological system, because we think that in order to understand how these systems work, we really need a lot of comparative research in different sorts of social-ecological systems over time and space.”

“Unfortunately, we don’t have all the research we would like yet, but we’re starting to make some in roads,” he said.

California has a complex water conveyance infrastructure and diverse ecosystems, and on top of that bio-physical system is a complex set of social and governance institutions. “The outcome of what happens in the Delta in terms of the sustainability of the resources or any of those other indicators you might be interested in is a function of not only what’s happening in the bio-physical system but also what’s happening in the governance system,” he said.

California has a complex water conveyance infrastructure and diverse ecosystems, and on top of that bio-physical system is a complex set of social and governance institutions. “The outcome of what happens in the Delta in terms of the sustainability of the resources or any of those other indicators you might be interested in is a function of not only what’s happening in the bio-physical system but also what’s happening in the governance system,” he said.

When you look at governance, you can’t just look at one institution. “You can’t look at just the Delta Stewardship Council or just Integrated Regional Water Management or just the Central Valley Flood Plan to understand the outcomes that are emerging from the governance system as it interacts with that bio-physical system,” he said. “Instead, we have to start thinking about looking at all of the different things simultaneously.”

A few years back, Dr. Lubell conducted a research project in the Bay Area where there were four separate planning and policy processes operating in basically the same geographical area. “I did a survey in that area where I tried to find all of the people who are interested in water management in the Bay Area using IRWM lists and some other lists, and I asked this question: ‘There are many different forums and processes available for participating water management and planning in the Bay Area.’ I gave the definition, ‘Planning processes are defined as forums where stakeholders make decisions about water management policies, projects, and funding,’ and then I asked them to list up to three different things they participated in,” Dr. Lubell said. “58% answered the question and the majority of them nominated three different institutions or policy processes they were playing in … How many total unique different policy processes do you think with that survey that I ended up with at the end of the day? … At least 100 different things going on simultaneously in the Bay Area around governance.”

A few years back, Dr. Lubell conducted a research project in the Bay Area where there were four separate planning and policy processes operating in basically the same geographical area. “I did a survey in that area where I tried to find all of the people who are interested in water management in the Bay Area using IRWM lists and some other lists, and I asked this question: ‘There are many different forums and processes available for participating water management and planning in the Bay Area.’ I gave the definition, ‘Planning processes are defined as forums where stakeholders make decisions about water management policies, projects, and funding,’ and then I asked them to list up to three different things they participated in,” Dr. Lubell said. “58% answered the question and the majority of them nominated three different institutions or policy processes they were playing in … How many total unique different policy processes do you think with that survey that I ended up with at the end of the day? … At least 100 different things going on simultaneously in the Bay Area around governance.”

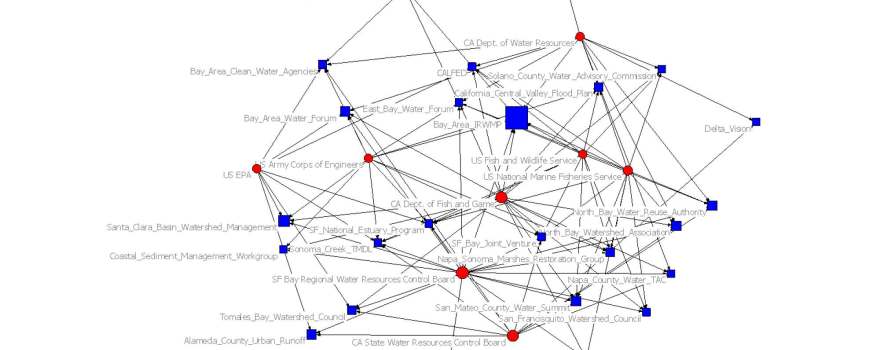

He then presented a diagram drawn using network science, explaining that the blue squares are all the different policy processes that people nominated as things they were participating in where important water management decisions were being made; the red circles there are different actors that are participating in these processes – some of them are survey respondents, some of them are actors that were nominated by the respondents.

He then presented a diagram drawn using network science, explaining that the blue squares are all the different policy processes that people nominated as things they were participating in where important water management decisions were being made; the red circles there are different actors that are participating in these processes – some of them are survey respondents, some of them are actors that were nominated by the respondents.

“So respondents might say they participate in one, and I would ask them what other agencies and actors are in there and they would give me a list, so I took those two lists and combined them and this is the picture you get out of that,” he said. “Each blue square is a particular policy process, and each red circle indicates and actor tied to that particular policy process via participation.”

“A lot of policy analysts will just pick out one of these squares and ask how well is IRWM working or how well is the Delta Stewardship Council working,” he said. “The work I’m doing is trying to expand that and say that what we have to try to do is understand how this entire system is structured and how it functions and how different policy processes within that system can be adjusted so that the system overall is able to adapt to the environmental problems that are occurring over time.”

He presented a slide showing the central parts to the system, noting that the Interregional Water Management Program is the biggest square. “At the time CalFed still existed, and a number of people did nominate CalFed, but it’s interesting to think, Cal Fed disappeared and has morphed into the Delta Stewardship Council and other sorts of institutions, which points out that these things are sort of dynamic. There are blue squares coming in and out, and actors coming in and out of these things.”

He presented a slide showing the central parts to the system, noting that the Interregional Water Management Program is the biggest square. “At the time CalFed still existed, and a number of people did nominate CalFed, but it’s interesting to think, Cal Fed disappeared and has morphed into the Delta Stewardship Council and other sorts of institutions, which points out that these things are sort of dynamic. There are blue squares coming in and out, and actors coming in and out of these things.”

Dr. Lubell noted that many of the processes in the center are various collaborative policy processes like the National Estuary Program and other watershed management groups, and a lot of the actors in the center are the big state and federal agencies, as well as some of the larger local agencies, such as EBMUD.

He presented a slide and said that he wouldn’t spend a lot of time on it but wanted to note that they have been developing a theoretical framework and some hypotheses about institutions and their processes. “The point is these issues are linked, the institutions are often dealing with multiple issues at one time, and then you have to scale this up to the level of the network diagram that I showed you earlier,” he said. “This little micro system occurs many, many times in the overall system.”

He presented a slide and said that he wouldn’t spend a lot of time on it but wanted to note that they have been developing a theoretical framework and some hypotheses about institutions and their processes. “The point is these issues are linked, the institutions are often dealing with multiple issues at one time, and then you have to scale this up to the level of the network diagram that I showed you earlier,” he said. “This little micro system occurs many, many times in the overall system.”

Dr. Lubell said he would be discussing three questions from the Center’s research:

- What structures of participation facilitate coordination?

- What variables influence the perceived effectiveness of different institutions?

- What determines the “payoffs” perceived by different actors?

In terms of the first question, Dr. Lubell said they have develop three hypotheses about how the systems are structured:

Institutions hypothesis: Collaborative institutions designed for policy coordination are more central in the network: “This hypothesis is that institutions like CalFed and the Delta Stewardship Council that take more of a collaborative inclusive approach are in the center of these networks and provide one of the main mechanisms by which coordination occurs throughout the system,” he said.

Actor hypothesis: Actors with greater capacity have more power in the network: “Another hypothesis is the actor hypothesis which is that there are particular types of actors that have the capacity to engage in coordination throughout the system,” he said. “In particular, state and federal agencies which have a lot of resources available to them – they have financial resources, a lot of expertise, and the authority of the state behind them if they want to do things like mandatory water conservation, and that provides them with the capacity that gives them power to coordinate within the system.”

“Risk” hypothesis (Berardo and Scholz 2010): Network closure facilitates cooperation: “There is a system. I’ll just give you an anecdote: Alejo here is a student in one of my classes, and he and I know each other, and he knows people in the DSC, if he introduces me to someone in the DSC, that in network terms is called closing a transitive triangle. So if Alejo does something really bad in class and I know the DSC person, I could call up that person and say, hey Alejo has done something bad in class, you don’t want to hire him. Hopefully he’ll do something really good in class and I’ll call up the DSC person and say, hey you should hire Alejo, he’s doing great, but we can go more cooperation with those sorts of closed network structure that allow reputation to spread.”

Dr. Lubell said they do a lot of statistical modeling of those networks. They start with descriptive statistics about the institutions that are central in that system, first classifying them as to what type of institutions they are, such as collaborative partnerships, joint powers authorities, advisory committees, interest group affiliations, and regulatory processes.

“What these results show is three different measures of centrality,” he said. “Those collaborative institutions such as Cal Fed are really more central in these networks, so they are at a place in the network that would allow them to fulfill some of the functions of coordination that they are expected to do, so that’s good news for the collaborative institutions. Regulatory processes, interestingly, are kind of low, because they are more adversarial, so they are not so much about collaboration, but they are more about adversarial decision making.”

“What these results show is three different measures of centrality,” he said. “Those collaborative institutions such as Cal Fed are really more central in these networks, so they are at a place in the network that would allow them to fulfill some of the functions of coordination that they are expected to do, so that’s good news for the collaborative institutions. Regulatory processes, interestingly, are kind of low, because they are more adversarial, so they are not so much about collaboration, but they are more about adversarial decision making.”

“If you look at centrality by the actor type, then the federal government and state government, as expected, are at the top of the list in terms of centrality, but also environmental special districts and water special districts,” he said. “What this reveals is that there’s another type of cooperation that is happening in the Delta and the Bay which is the formation of interest group coalitions who are advocating for their particular viewpoints on the tunnels or other policy preferences that they are expressing over time, and this is where a lot of the politics comes from.”

“If you look at centrality by the actor type, then the federal government and state government, as expected, are at the top of the list in terms of centrality, but also environmental special districts and water special districts,” he said. “What this reveals is that there’s another type of cooperation that is happening in the Delta and the Bay which is the formation of interest group coalitions who are advocating for their particular viewpoints on the tunnels or other policy preferences that they are expressing over time, and this is where a lot of the politics comes from.”

“So within the system, we have structural evidence that there’s coordination going on mainly by these collaborative policy venues in the agencies, but there’s also coordination in terms of how the interest groups and different actors are working together to advocate for their preferences,” he said.

For the statistical modeling, they used special simulation models to simulate what these networks look like shows. “There are a lot of closure in these networks that are thought to facilitate cooperation and that closure is actually centered on collaborative institutions and state and federal agencies, so that’s additional evidence about how those institutions and actors are facilitating cooperation within these systems,” Dr. Lubell said. “But also so are the water special districts and environmental groups, which means there’s the political coalitions there, too.”

Those collaborative institutions also fulfill important brokerage roles. “This is to say that when you look at something like CalFed, they’re involved in structural aspects of the network where they are linking together different types of institutions,” he explained. “So they might link together an advisory committee and a regulatory institution, so to the extent that these systems are fragmented, there’s a niche for those collaborative institutions to come in and try to link together some of those and fill some of those holes that cause fragmentation.”

Dr. Lubell then turned to how these institutions function. “There is some link between structure and function, but it’s nice to start thinking about which of these squares are more effective than some of the other ones, so we try to get some clues about the function aspects of these systems.”

They did a comparative institutional ecology study between systems in Parana, Argentina; Tampa Bay, Florida, and the California Delta. “Obviously there’s a ton of overlap between the San Francisco Bay and the Delta governance systems in terms of the institutions and the actors that are involved, but with the comparative studies, we used the same exact survey to ask questions of the water management actors in those different systems so that we can start to think about why systems look different in different places,” he said. “In the long term, that really is something we have to do a lot more of to understand why is the Delta different from whatever other systems that we’re thinking about.”

“Within that, I’m going to talk about why people perceive institutions that they participate in to be more or less effective and also whether or not they perceive those institutions to be generating conflict or cooperation,” he said.

He explained that for the empirical analysis, each survey respondent is asked what institutions they participate in; they nominate an institution, and they are then asked how effective the respondents think they are in solving problems, how fair they perceive them to be, and other questions that are indicators of their perceptions about the institution’s efficacy. Survey respondents were also asked if they thought the institution provides conflicts or is providing more mutually beneficial payoffs.

He explained that for the empirical analysis, each survey respondent is asked what institutions they participate in; they nominate an institution, and they are then asked how effective the respondents think they are in solving problems, how fair they perceive them to be, and other questions that are indicators of their perceptions about the institution’s efficacy. Survey respondents were also asked if they thought the institution provides conflicts or is providing more mutually beneficial payoffs.

“Then we can aggregate across all the actors and institutions and do the analysis about what is it about -the dyad here is the unit of analysis, the actor paired with the institution, and the dependent variables to things you are trying to explain,” he said.

“The first perspective is what causes perceptions of policy effectiveness, or what is at least correlated with it,” Dr. Lubell said. “There’s a theoretical perspective that comes from institutional economics that says when you look at interactions within the context of one of these institutions is what are the costs of cooperation and what are the costs of having a political agreement or a transaction that enables people to find mutually beneficial solutions.”

“So if you’re trying to come up with an agreement, you have to search for all the different possible solutions, and once you discover the range of possible solutions that are out there, you would bargain over what the distribution of costs and benefits that come from those different solutions,” he said. “Once some sort of agreement is reached, you would have to monitor and enforce the resulting agreement, and so you look for factors that increase or decrease those transactions costs – for example, scientific knowledge. If people are pretty confident in the science that’s being provided about decision making within the system, then they are going to have an easier time of figuring out what are the options, what is the distribution of costs and benefits that are available from each of those options, and how can we best monitor things after the fact and enforce that agreement, so scientific knowledge clarifies things and helps to reduce those transaction costs.”

Heuristically, one of the factors of policy effectiveness would be scientific knowledge; political knowledge is another one – how well they understand the interests of the other actors involved, participation, and how much experience they have, he said. There are a number of variables that can be put into a model.

He then presented a graph depicting the influence of political knowledge versus the influence of scientific knowledge across all three systems studied. “The size of these bars indicate how important scientific knowledge is to predicting their views on efficacy,” he said. “So for example in California and in Tampa Bay, scientific knowledge has a really important effect on people’s perceptions of effectiveness. One way to read that is in the Delta, what the Delta Science Program doing is really important. If you can create the impression through doing good science that there really is a scientific basis to the decision making, people are going to view the overall set of decisions throughout the system as more effective and have a greater buy into it.”

He then presented a graph depicting the influence of political knowledge versus the influence of scientific knowledge across all three systems studied. “The size of these bars indicate how important scientific knowledge is to predicting their views on efficacy,” he said. “So for example in California and in Tampa Bay, scientific knowledge has a really important effect on people’s perceptions of effectiveness. One way to read that is in the Delta, what the Delta Science Program doing is really important. If you can create the impression through doing good science that there really is a scientific basis to the decision making, people are going to view the overall set of decisions throughout the system as more effective and have a greater buy into it.”

“In Argentina, it’s not so important,” he said. “What’s more important is the amount of political knowledge they have. … There’s a lot of possible reasons that comparative difference could be there. We believe that one of the interesting explanations is that in Argentina, there is low institutional development. There are weak national institutions there; with water management, they keep trying things and then failing. … In a developing country like Argentina, they are in this constant process of trying to create institutions, and so from the governance perspective, that political knowledge seems to be really important. It’s like the startup costs. The political knowledge has to be there first; once that is established, then the scientific knowledge becomes a more important thing.”

“Another way to think about it is in California, most people involved in California water politics know pretty well what the political interests are of a lot of the different actors, so they’ve put that issue to bed,” Dr. Lubell said. “Now they are thinking more about what does the science say, and then given the distribution of political interests, what is the science saying about the distribution of benefits and costs of different sorts of policy programs.”

A member of the audience asks where the media fits into this overall scheme.

“The way that this statistical model is built is from the perspective of actors participating in each institution, so we didn’t ask the question about to what extent do you interact with media, so we don’t really have a measure for that,” he said. “That would be a candidate for further study. I can think of some ways we can get at that, but that’s not taken into account in this particular analysis.”

Dr. Lubell then turned to the perceived payoffs in policy games. Survey respondents were asked, which statement best characterizes the typical decision process about the water forums they participated in – do most groups gain as long as they can develop common policy, is there conflict over who will gain the most, or one group’s gain involves another group’s loss?

He then presented a diagram of results from the four study sties. “When you look at how people perceive a particular institution, there’s a lot of heterogeneity so if you find ten people that say the participate in the DSC, they are going to have a diverse view on whether or not it’s mutually beneficial or are there tradeoffs or is it really about a zero sum game,” Dr. Lubell explained. “So it’s not that everybody is on the same page with respect to how they perceive it.”

He then presented a diagram of results from the four study sties. “When you look at how people perceive a particular institution, there’s a lot of heterogeneity so if you find ten people that say the participate in the DSC, they are going to have a diverse view on whether or not it’s mutually beneficial or are there tradeoffs or is it really about a zero sum game,” Dr. Lubell explained. “So it’s not that everybody is on the same page with respect to how they perceive it.”

“The second point is that when you look at the breakdown of how people perceive those payoffs, you can see on average, the majority of people sort of see things as mutually beneficial,” he said. “In our systems, it’s not like we’re walking through and everybody sees heavy conflict, but if you look at California, California has the least of the cooperation or at least close to the bottom of cooperation, but it has by far the highest perceptions of conflict.”

“The second point is that when you look at the breakdown of how people perceive those payoffs, you can see on average, the majority of people sort of see things as mutually beneficial,” he said. “In our systems, it’s not like we’re walking through and everybody sees heavy conflict, but if you look at California, California has the least of the cooperation or at least close to the bottom of cooperation, but it has by far the highest perceptions of conflict.”

Comparing the responses from California stakeholders to Tampa Bay and Parana stakeholders, far more of them say that California is experiencing zero sum conflicts over water management, he said. “This is from the Delta and I think this pattern is going to be repeated over time. It may be even worse now, because we did this initial study in 2012. It’s going to be potentially worse now with the drought.”

In Parana, they don’t have a lot of cooperation but trade-offs have more importance. “There are two potential reasons there that I think are candidate reasons,” he said. “One is a developing country perspective where when you’re in an early stage of institutional development, those tradeoffs become more important to think about. Another perspective is that there’s some sort of cultural differences there between the US and Latin America and political systems where they think about tradeoffs as more realistic part of what goes on in those systems. That’s something that we’re not sure about, and we have to speculate on why that difference occurs, but clearly there are comparative differences in how people are seeing things.”

Another set of questions they ask survey respondents is how many players are in each game, what is the diversity of organizations in the game, and how diverse are the issues being considered in the game. Their responses are measured using the Herfindahl index, which is a measurement of diversity. “When we do that, we find that organizational diversity is linked to having lots of conflict,” Dr. Lubell said, explaining that with this index, high numbers mean low diversity and low numbers mean high diversity. “With low organization diversity, this is where you typically have the mutual gains and the cooperation parts, but when organizational diversity is high, which is the inverse of this bar, then you have a lot more conflicts and issues don’t matter as much, which I think is interesting.”

Another set of questions they ask survey respondents is how many players are in each game, what is the diversity of organizations in the game, and how diverse are the issues being considered in the game. Their responses are measured using the Herfindahl index, which is a measurement of diversity. “When we do that, we find that organizational diversity is linked to having lots of conflict,” Dr. Lubell said, explaining that with this index, high numbers mean low diversity and low numbers mean high diversity. “With low organization diversity, this is where you typically have the mutual gains and the cooperation parts, but when organizational diversity is high, which is the inverse of this bar, then you have a lot more conflicts and issues don’t matter as much, which I think is interesting.”

He then presented another set of graphs, noting that on these graphs, higher numbers do mean more organizational diversity. “This is the probability that given the diversity in the game that people play, what is the probability that they select cooperative payoffs, tradeoff payoffs, or conflict payoffs?” he said. “You can see as organizational diversity goes up, they are less likely to select cooperative payoffs and more likely to select conflict payoffs, so when you have an inclusive collaborative sort of institution that brings in lots of different types of actors with lots of different types of preferences, you’re actually more likely to get people saying there are zero sum conflicts happening in those sorts of institutions, which is somewhat bad news. … You should expect conflict, especially at first, when you open up these processes and invite lots of sorts of institutions in.”

He then presented another set of graphs, noting that on these graphs, higher numbers do mean more organizational diversity. “This is the probability that given the diversity in the game that people play, what is the probability that they select cooperative payoffs, tradeoff payoffs, or conflict payoffs?” he said. “You can see as organizational diversity goes up, they are less likely to select cooperative payoffs and more likely to select conflict payoffs, so when you have an inclusive collaborative sort of institution that brings in lots of different types of actors with lots of different types of preferences, you’re actually more likely to get people saying there are zero sum conflicts happening in those sorts of institutions, which is somewhat bad news. … You should expect conflict, especially at first, when you open up these processes and invite lots of sorts of institutions in.”

Dr. Lubell is asked for an example of a zero sum conflict.

“I think the classic one in California that people perceive is classic zero sum conflict is water supply versus biodiversity in the Delta,” he replied. “If you export more water, you decrease biodiversity and there’s no way to find a mutually beneficial tradeoff between them, according to some people. Some people have a different view. Well we can actually get both, we can have the coequal goals, we can have the tunnels and the habitat stuff, or now the scaled back part of the habitat stuff and get environmental benefits and water supply benefits out of it. This is where the science becomes quite important in terms of actually delineating what those possibilities are because right now, there’s a large amount of different perceptions about whether or not such issues are zero sum versus mutually beneficial.”

Dr. Lubell noted that the surveys are what people self-reported. “This is their own self reports of how they perceived their participation in these programs, and by the way, the largest program in California, the most people reported participating in was BDCP, so if you wanted to get rid of all the rest of the institutions and just focus on BDCP, you’re going to see in the BDCP a lot of people saying zero-sum conflicts.”

Another important finding was that the more people and the more organizations that are involved leads to more conflict. “The fact that the diversity of issues and the number of issues do not really have a big influence on the amount of conflict I think is good news,” he said. “If you want to think about how to structure these things, we don’t necessarily have to be afraid of addressing multiple issues. We can bring in all the different ecosystems in the Delta and maybe we’re not going to have a huge impact on the amount of conflict that occurs.”

“In fact there’s some indicative results that when you bring in multiple issues, that you might see more tradeoffs,” he continued. “In other words, by bringing in multiple issues, you can think about integrating across them and finding ways to link them together, like the classic example is conjunctive use. Instead of groundwater and surface water being managed separately, maybe if we jointly manage groundwater and surface water conjunctively, we can find some ways to increase the overall benefits.”

“The fact that with lots of actors and more diverse actors, you get more conflict, means you really have to close attention to the composition of these groups,” Dr. Lubell said. “One of the big things that people talk about is trying to invite people who can play well with others. And so there’s a weird paradox there – they say we’re going to invite everybody to the table, and then they sit down and say who are we really going to invite to the table; the answer to who we really invite to the table is the people who can play well with others and leave the grenade throwers outside the process because you know that if they come into the process, what they are going to do is cause a lot of conflict. I’ve heard that a million times talking to people about how they really make decision about who to invite. You don’t capture that necessarily in the statistical analysis here, but that’s an important consideration.”

Dr. Lubell then gave his three conclusions:

Government agencies and collaborative institutions are primary coordinating mechanisms embedded in “closed” networks. “It looks to us that within places like the Delta and also other places, that government agencies and collaborative institutions are kind of embedded in social networks in ways that helps them facilitate coordination throughout the system, which I think is good news for the proponents of those particular approaches,” he said.

Scientific and political knowledge reduce transaction costs/enhance effectiveness of individual games, possibly different across contexts: “There is some evidence that scientific and political knowledge reduces transaction costs and enhance at least perceived effectiveness of individual blue squares or institutions within the system,” he said. “That varies across context, but I think that should be taken to heart by a group like this where you spend a lot of time trying to facilitate scientific knowledge throughout the system. I think that process has value in these systems, at least in places where the institutions are already fairly well developed.”

Conflict payoff perceptions driven mainly by “game” level variables, especially organizational diversity: “Who shows up at the table is making a big difference with greater numbers of actors and more diverse actors actually being a situation where conflict is more likely to occur. Which in some senses goes against what the philosophy of collaborative institutions are, which is bring everybody to the table in order to get cooperation.”

These three findings start to give some insight, but there are a lot of other questions about how these systems are structured and functioned, how can we manage them, and how can we engineer these complex governance systems, he said. “To me, these messy systems are the fundamental reality of governance that exists in California and basically every major watershed in the US, and I think most major watersheds in the world are going to have some version of this happening,” he said. “The outcomes of governance and environmental policy happen in this complex system. We need to know what its structure is, we need to know how it functions, before we can make really strong policy recommendations about what to do. We’re starting to get there but we have a lot more to do, and especially looking over time in a place like the Delta.”

“Until we really look at a lot of systems over space, over time, comparatively, we aren’t going to be able to say, very strong things about what are the factors that we should think about in terms of engineering these systems,” he said. “Eventually I’d like to get there, and I suppose if you can spend hundreds of billions of dollars to look at a couple rocks on Mars, we can ask the NSF for a couple million to explore governance systems which are at least as important to human well being on this planet as finding a rock on Mars.”

“So that’s it … “

The floor was then opened up for questions.

Question: Regarding the nuances of collaboration and who comes to the table, what about the fear of reprisal, bringing people into a policy game so that they don’t come and sue you later or complain later that they weren’t involved.

“One way to think about that is in a collaborative institution where you’re inviting a lot of people to the table, and by inviting people, you are also inviting conflict, one thing that we are not able to look at is what would happen without that institution. What is the counter factual? You can think, why would you ever have a collaborative institution if you’re not willing to resolve conflict? So if you’re going to create IRWM, one way to think of it is would you really invite all the people who are already working well together, or would you actually invite the people that are having some problems finding agreement to try to forge agreement where conflict is occurring? … People who are excluded from these processes do have other venues where they can go – the courts, or another one of these blue squares or the legislature, so that’s an important piece of the puzzle.”

Question: When you’re in government, you’ve got to be inclusive to a certain level, some of its required by statute, some of its required because there are new laws in effect that will require those particular actors and voices to be heard. So how do we get to that point going forward?

“We did actually investigate whether or not people who represent government agencies are more likely to see things from a mutually beneficial standpoint. You might think the government people are going to try and take this brokerage position, but on average, people that work in various government agencies are just the same as the rest of the stakeholders, which means of course government agencies have these crazy things in them called people, and those people also have different ideologies and preferences that they expressing on this survey, so greater training among government employees about their brokerage roles, about trying to deal with multiple stakeholders might be something that might be useful in this context. Conflict resolution facilitation might help on a more widespread basis.”

Note: Brown Bag Seminars are jointly presented by The Delta Science Program, Ecosystem Restoration Program & Surface Water Ambient Monitoring Program.

For more information …

- For more on Dr. Lubell’s research, click here to visit the Center for Environmental Policy and Behavior online.

- To watch this brown bag seminar, click here.

Help Maven bridge the funding gap!

Help Maven bridge the funding gap!

Your help is needed for Maven’s Notebook to continue operations in 2016.